Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

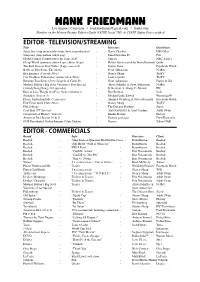

Hank Friedmann CV

HANK FRIEDMANN Los Angeles, California • [email protected] • hankf.com Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (IATSE Local 700) & CSATF Safety Pass certified ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - TELEVISION/STREAMING Title Directors Distributor Santa, Inc (stop motion television show, in production) - Harry Chaskin HBO Max Simpsons (stop motion couch gag) - John Harvatine IV Fox Global Citizen Countdown to the Prize 2020 - Various NBC & Int’l Gloop World (animatic editor 5 eps, editor 15 eps) - Helder Sun (created by Justin Roiland) Quibi The Real Bros of Simi Valley (5 eps, season 3) - Jimmy Tatro Facebook Watch Between Two Ferns: The Movie - Scott Aukerman Netflix Blackspiracy (Comedy Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Can You Beat Yamaneika? (Game Show Pilot) - Lauren Quinn TruTV Between Two Ferns (Jerry Seinfeld & Cardi B.) - Scott Aukerman Funny or Die Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special - Akiva Schaffer & Scott Aukerman Netflix Comedy Bang Bang (110 episodes) - B. Berman, S. Sharp, D. Jelinek IFC How to Lose Weight in 4 Easy Steps (Sundance) - Ben Berman Jash Snatchers (Season 3) - Michael Lukk Litwak Warner/go90 Please Understand Me (5 episodes) - Ahamed Weinberg & Steven Feinartz Facebook Watch End Times Girls Club (Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Flulanthropy - The Director Brothers Seeso Cool Dad (TV Special) - Alex Kavutskiy & Ariel Gardner Adult Swim Crossroads of History “Lincoln” - Marko Slavnic History American Idol Season 10 & 11 - Remote packages Ford/Fremantle GOP Presidential Online Internet Cyber Debate - Various Yahoo!/FoD ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - COMMERCIALS Brand Info Directors Client Reebok - Allen Iverson/Question Mid Double Cross - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - Gigi Hadid “Wild is Wherever” - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - FW19 Trail - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B: Aztrek” - Eric Notarnicola Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B vs. -

Racism and Bad Faith

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gregory Alan Jones for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Philosophy, Philosophy and History presented on May 5, 2000. Title: Racism and Bad Faith. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Leilani A. Roberts Human beings are condemned to freedom, according to Jean-Paul Sartre's Being and Nothingness. Every individual creates his or her own identity according to choice. Because we choose ourselves, each individual is also completely responsible for his or her actions. This responsibility causes anguish that leads human beings to avoid their freedom in bad faith. Bad faith is an attempt to deceive ourselves that we are less free than we really are. The primary condition of the racist is bad faith. In both awarelblatant and aware/covert racism, the racist in bad faith convinces himself that white people are, according to nature, superior to black people. The racist believes that stereotypes ofblack inferiority are facts. This is the justification for the oppression ofblack people. In a racist society, the bad faith belief ofwhite superiority is institutionalized as a societal norm. Sartre is wrong to believe that all human beings possess absolute freedom to choose. The racist who denies that black people face limited freedom is blaming the victim, and victim blaming is the worst form ofracist bad faith. Taking responsibility for our actions and leading an authentic life is an alternative to the bad faith ofracism. Racism and Bad Faith by Gregory Alan Jones A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Presented May 5, 2000 Commencement June 2000 Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Acknowledgment This thesis has been a long time in coming and could not have been completed without the help ofmany wonderful people. -

Mister America

Presents MISTER AMERICA A film by Eric Notarnicola 86 mins, USA, 2019 Language: English Distribution Mongrel Media Inc 217 – 136 Geary Ave Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filming took place on location in San Bernardino and the Los Angeles area. Using a mix of actors and non-actors, the small crew used documentary techniques to give the experience of a true story unfolding in real time. Often filming in four to five locations a day and using a script in which specific dialogue was scarce but the intention for each scene was detailed, actors improvised fully in the moment to allow their characters to develop naturally. What resulted was a team in-sync and fully ready to capture the chaotic world around them. 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com 1. ABOUT THE CAST As one half of comedy duo “Tim and Eric” and creator of Abso Lutely Productions, Tim Heidecker can easily be viewed as a godfather of subversive, alt-comedy. With roles in “Us”, “Eastbound & Down”, “Awesome Show”, “Portlandia” and more, Mr. Heidecker has helped to affect the comedy landscape for years to come. As a co-creator of On Cinema and its ensuing worlds with Gregg Turkington, he’s been able to prod at multiple facets of society. -

Museum of the Moving Image Presents Month-Long Screening Series 'No Joke: Absurd Comedy As Political Reality'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE PRESENTS MONTH-LONG SCREENING SERIES ‘NO JOKE: ABSURD COMEDY AS POLITICAL REALITY’ Personal appearances by The Yes Men and PFFR, new work by Tim Heidecker and Gregg Turkington, and films by Chaplin, Spike Lee, Scorsese, Bruno Dumont, and more October 9–November 10, 2019 Astoria, New York, September 12, 2019—MoMI presents No Joke: Absurd Comedy as Political Reality, a fourteen-program series that chronicles some of the most inventive and ingenious ways artists—from Charlie Chaplin to The Yes Men—have reckoned with their political environments. The series features work by filmmakers and other entertainers who are producing comedy and satire at a time when reality seems too absurd to be true. Organized by guest curator Max Carpenter, No Joke opens October 7 with Mister America, the new pseudo-documentary by the comedy duo Tim Heidecker and Gregg Turkington—which will be presented at multiple venues on the same night—and continues through November 10, with films including General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait; William Klein’s Mr. Freedom; Bruno Dumont’s Li’l Quinquin and Coincoin and the Extra-Humans; Spike Lee’s Bamboozled; Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux; Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street; the Adult Swim TV series Xavier: Renegade Angel, with creators PFFR in person; Dusan Makavejev’s The Coca-Cola Kid; Starship Troopers; and TV Carnage, by Ontario artist Derrick Beckles. Among other special events are Heidecker and Turkington’s 2017 comic epic The Trial, followed by a live video conversation with the duo, and An Evening with The Yes Men, featuring the activist prankster team of Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonnano in person for a conversation with clips of their greatest stunts. -

1 a Comedy of Errors Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love

A Comedy of Errors or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Sensibility- Invariantism about ‘Funny’ Ryan Doerfler Abstract: In this essay, I argue that sensibility-invariantism about ‘funny’ is defensible, not just as a descriptive hypothesis, but, as a normative position as well. What I aim to do over the course of this essay is to make the realist commitments of the sensibility- invariantist out to be much more tenable than one might initially think them to be. I do so by addressing the two major sources of discontent with sensibility-invariantism: the observation that discourse about comedy exhibits significant divergence in judgment, and the fact that disagreements about comedy, unlike disagreements about, say, geography, often strike us as fundamentally intractable. Consider the following scenario: Jane (27 years old) and Sarah (nine) are together on the couch watching an episode of Arrested Development. While Jane thinks that the show is utterly hilarious and is, as a result, having a wonderful time, Sarah finds the show slightly confusing and is, as a result, rather bored. During a commercial break, Jane turns to Sarah and says, ‘Arrested Development is incredibly funny!’ In the above scenario, Sarah will likely respond by saying something like, ‘I don’t think it’s very funny,’ a response that Jane will regard as an attempt to call into question her preceding assertion. Given the circumstances, it is likely that will make certain concessions (e.g., ‘Oh… well yes I can see how the show’s humor is probably a bit lost on someone your age.’). -

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler

The Note−Books of Samuel Butler Samuel Butler The Note−Books of Samuel Butler Table of Contents The Note−Books of Samuel Butler..........................................................................................................................1 Samuel Butler.................................................................................................................................................2 THE NOTE−BOOKS OF SAMUEL BUTLER...................................................................................................16 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................17 BIOGRAPHICAL STATEMENT...............................................................................................................20 I—LORD, WHAT IS MAN?.......................................................................................................................24 Man........................................................................................................................................................25 Life........................................................................................................................................................26 The World..............................................................................................................................................27 The Individual and the World................................................................................................................28 -

The Suspension of Seriousness

CHAPTER ONE Matters of Life and Death And López Wilson, astigmatic revolutionist come to spy upon his enemy’s terrain, to piss on that frivolous earth and be eyewit- ness to the dying of capitalism while at the same time enjoying its death-orgies. —Carlos Fuentes, La región más transparente (1958) Introduction wentieth-century Mexican philosophy properly considered boasts Tof a number of great thinkers worthy of inclusion in any and all philosophical narratives. The better known of these, Leopoldo Zea, José Vasconcelos, Antonio Caso, Samuel Ramos, and, to a great extent, Octavio Paz, have received their fair share of attention in the United States over the last fifty years, partly due to a concerted effort by a few philosophy professors in the US academy who find it necessary to dis- combobulate the Eurocentric philosophical canon with outsiders. For reasons which I hope to make clear in what follows, Jorge Portilla is not one of these outsiders to which attention has been paid—even in his homeland, where he is more likely to be recognized, not as one of Mex- ico’s most penetrating and attuned minds, but rather by his replicant, López Wilson, a caricature of intelligence and hedonism immortalized by Carlos Fuentes in his first novel. This oversight is unfortunate, since Portilla is by far more outside than the rest; in fact, the rest find approval precisely because they do not stray too far afield, keeping to themes and methodologies in tune with the Western cannon. One major reason for 1 2 The Suspension of Seriousness the lack of attention paid to Portilla has to do with his output, restricted as it is to a handful of essays and the posthumously published text of his major work, Fenomenología del relajo. -

Comedic Devices Funsheet

!Find The Funny: Comedic Devices Funsheet Every comedic script uses comedic devices. A single scene will contain multiple comedic devices. Use this list of comedic devices to identify where and how the writer is expressing the comedy in your audition scenes. Then use your discoveries to inform your acting choices! Gaffe – An act or remark causing embarrassment by shattering a social construct. These are usually embarrassing to the characters (and funny to us) because they are done/seen/found out in public. • Conscious Gaffe – Character is aware they are going to be embarrassed but you do it anyway. • Unconscious Gaffe- Character isn’t aware of their Gaffe / that it is a gaffe. Opposites - What makes reversals and unexpected moments work. Play both with conviction and highlight the opposites to get the biggest laugh. Social Awkwardness – A moment that draws its humor from one or multiple characters being socially uncomfortable. This device revolves around anxiety of social interactions (either in general or with one particular person). This can come from the fear of being rejected/made fun of, not knowing what to say, etc. Overstatement – Hyperbole. An extreme magnification or exaggeration. It blows something completely out of proportion for a distorted effect. Happens often when a character puts huge value on something that, to us, seems trivial. Understatement – Making something seem much less than what it is. An under-exaggeration. Copyright Acting Pros Studio 2016 1 !Find The Funny: Comedic Devices Funsheet Verbal Irony – What is said is the opposite of the meaning. Situational Irony – What happens is the opposite of what is expected. -

Podcast Directory of Influencers

The Ultimate Directory of Podcasters 670 OF THE WORLD’S LEADING PODCASTERS Who Can Make You Famous By Featuring YOU On Their High-Visibility Platforms Brought to you by & And Ken D Foster k Page 3 1. Have I already been a guest on other shows? 3. Do I have my own show, or a substantial online presence, and Let’s face it, you wouldn’t have wanted your first TV interview have I already connected with, featured, or had a podcaster on to be with Oprah during her prime, or your first radio interview my show? with Howard Stern during his. The podcasters featured within these pages are the true icons of the podcasting world. You When seeking to connect with podcasters, it is certainly easier have ONE shot to get it right. Mess it up and not only will to do so if you’re an influencer in your own right, have existing you never be invited back to their show, given that the world relationships with other podcasters and/or have a platform that of podcasters is tight, word will spread about your rivals theirs. Few, however, will meet one, let alone all three, of appearance and the odds of being invited onto others’ shows these criteria. There is, however, an easy solution. Rather than will be dramatically reduced. wait for someone to come to your door and ‘anoint’ you as being ready to get onto the influencer playing field, take matters into Recommendation: Cut your teeth on shows with significantly your own hands and start embodying the character traits, and less reach before reaching out for those featured in this replicating the actions, of influencers you admire. -

EMILY TING 2008 N ALVARADO STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90039 TEL: 651.442.2545 EMAIL: [email protected]

EMILY TING www.emilyting.com 2008 N ALVARADO STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90039 TEL: 651.442.2545 EMAIL: [email protected] SELECTED CREDITS TELEVISION 2016 Costume Designer Broken Thank You, Brain! / ABC Digital 2016 Costume Designer Comedy Bang! Bang! Abso Lutely Productions / IFC 2015 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 4 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2015 Costumer Why? With Hannibal Buress Comedy Central 2014 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 3 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer Check It Out! With Dr. Steve Brule Season 3 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer Hannibal Buress: Unemployable (Pilot) JAX Media / Comedy Central 2013 Costume Designer Candy Ranch (Pilot) Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 2 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim ADVERTISING 2016 Costume Designer Eric Andre at the RNC and DNC Promos Abso Lutely Productions 2015 Costume Designer USAA: Car Buying Service Sandwich Video 2015 Costume Designer Ruffles: Ridgiculous HeLo 2015 Costume Designer Toyota Camry: Fatherʼs Day Video Buzzfeed 2015 Costume Designer Why? With Hannibal Buress Promos Comedy Central 2014 Costume Designer American Legacy: Erase and Replace PSA Abso Lutely Productions 2013 Costume Designer Guinness : The Colorful World of Black Prologue 2013 Costume Designer Motorola: Tim and Ericʼs First Vacation Jash 2013 Costume Designer Nick Offerman Paddle Your Own Canoe Promo Funny or Die 2013 Costume Designer Groupon: Imagine Sandwich Video 2013 Costume Designer Zipcar: Wheels When You Want Them Sandwich Video 2013 Costume Designer Intel: Big Box Odd Machine FEATURE FILM 2011 Wardrobe Supervisor Nancy, Please Small Coup Films / dir. -

Mplc Studio Liste 2020

MPLC STUDIO LISTE 2020 STUDIOS – PRODUZENTEN – FERNSEHSTATIONEN MPLC STUDIO LISTE 2020 STUDIOS – PRODUCTEURS – STATIONS DE TÉLÉVISION MPLC LISTA STUDIO 2020 CASE CINEMATOGRAFICHE – PRODUTTORI – STAZIONI TELEVISIVE MOTION PICTURE LICENSING COMPANY: DER WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE LIZENZGEBER IN DER FILM- & TV-BRANCHE. MPLC Switzerland GmbH Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach CH-8034 Zürich MPLC ist der weltweit grösste Lizenzgeber für öffentliche Vorführrechte im non-theatrical Bereich und in über 30 Länder tätig. Ihre Vorteile + Einfache und unkomplizierte Lizenzierung + Event, Title by Title und Umbrella Lizenzen möglich + Deckung sämtlicher Majors (Walt Disney, Universal, Warner Bros., Sony, FOX, Paramount und Miramax) + Benutzung aller legal erworbenen Medienträger erlaubt + Von Dokumentar- und Independent-, über Animationsfilmen bis hin zu Blockbustern ist alles gedeckt + Für sämtliche Vorführungen ausserhalb des Kinos Index MAJOR STUDIOS EDUCATION AND SPECIAL INTEREST TV STATIONS SWISS DISTRIBUTORS MPLC TBT RIGHTS FOR NON THEATRICAL USE (OPEN AIR SHOW WITH FEE – FOR DVD/BLURAY ONLY) WARNER BROS. FOX DISNEY UNIVERSAL PARAMOUNT PRAESENS FILM FILM & VIDEO PRODUCTION GEHRIG FILM GLOOR FILM HÄSELBARTH FILM SCHWEIZ KOTOR FILM LANG FILM PS FILM SCHWEIZER FERNSEHEN (SRF) MIRAMAX SCM HÄNSSLER FIRST HAND FILMS STUDIO 100 MEDIA VEGA FILM COCCINELLE FILM PLACEMENT ELITE FILM AG (ASCOT ELITE) CONSTANTIN FILM CINEWORX Label Apollo Media Apollo Media Distribution Gmbh # Apollo Media Nova Gmbh 101 Films Apollo ProMedia 12 Yard Productions Apollo ProMovie 360Production -

2019-20 Fordham Swimming & Diving

2019-20 FORDHAM SWIMMING & DIVING PRIMARY LETTER MARK QUICK FACTS Table of Contents Location: Bronx, NY 10458 SWIMMING & DIVING INFORMATION Quick Facts/Mission Statement/Credits: 1 Founded: 1841 Head Coach: Steve Potsklan Around Fordham/Social Networks/ Enrollment (Undergraduate): 8,855 Alma Mater/Year: Penn State ‘85 BLACK BACKGROUND USAGE Directions: 2 Nickname: Rams Office Phone Phone: (718) 817-4256 Colors: Maroon and White Assistant Coach Hayley Masi SINGLE COLOR VERSION The CoachingEMBROIDERY VERSION Staff Home Pool: Messmore Aquatic Center Assistant Coach Ed Cammon FORDHAM MED. GREY FORDHAM MAROON FORDHAM BLACK Affiliation: NCAA Div. I Diving Coach Zhihua Hu PANTONE BLAHeadCK 30% PANTONE 209 C CoachPANTONE BLACK Steve Potsklan: 4-5 Assistant Coach Hayley Masi: 6 Conference: Atlantic 10 2018-19 Women’s Record: 7-0 Assistant Coach Ed Cammon: 5 President: Joseph McShane, S.J. 2019 Atlantic 10 Women’s Finish: Third Diving Coach Zhihua Hu: 6 Vice President for Student Affairs: Jeffrey Gray 2018-19 Men’s Record: 3-4 Volunteer Assistant Coach Steve Sholdra: 6 2019 Atlantic 10 Men’s Finish: Eighth ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT PERSONNEL Director of Intercollegiate Athletics: David Roach SPORTS INFORMATION/MEDIA RELATIONS 2019-20 Swimming & Diving Deputy Dir. of Intercoll. Athletics: Charlie Elwood Director of Sports Media Relations: Joe DiBari 2019-20 Rosters: 7-8 Sr. Assoc. Athletic Director/Business: John Barrett SID Office Phone: (718) 817-4240 2019-20 Athlete Profiles: 9-32 Sr. Assoc. Athletic Dir./SWA: Djeanne Paul SID Fax: (718) 817-4244 2018-19 Top Times & Scores 33-34 Assoc. Ath. Director/Marketing: Nick LaMarca Associate SID (Water Polo): Scott Kwiatkowski The Atlantic 10 35 Assoc.