Teh Tarik with the Flag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poh See Tan Eating House 22 Sin Ming Road

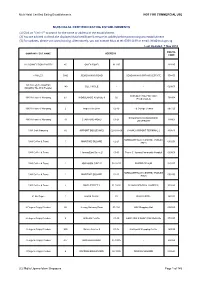

Name: Gourmet Street (CW) Name: Gourmet Street (KC) Name: Gourmet Street (SMR) Name : Poh See Tan Eating House 710 Clementi West Street 131 Jalan Bukit Merah 22 Sin Ming Road #01-210 194 Kim Keat Ave. QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR + TERMINAL Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Gourmet Street (CW) Wangwang Meishi Gourmet St (KC) Jin Sheng Mixed Veg Rice Gourmet Street (SMR) Poh See Tan Eating House Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Gourmet Street (SMR) Poh See Tan Eating House Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Gourmet Street (SMR) Poh See Tan Eating House Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Gourmet Street (SMR) Poh See Tan Eating House Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Gourmet Street (SMR) Poh See Tan Eating House Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Guo Chang Mala S1 Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet St (KC) Ji De Lai S6 Gourmet Street (CW) Sin Kian Heng S4 Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet Street (CW) Gourmet Street (CW) 12 1 7 1 8 5 No of Merchants 34 Name: Gourmet Street (JB27) Name: 8 Plus Food House Name: 8 Plus Food House 27 Jalan Berseh 95 Lorong 4 Toa Payoh #01-74 8 Lorong 7 Toa Payoh QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR QR + TERMINAL QR Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Trading Name Gourmet St (JB27) Chong Qing 8 Plus Food House FISH SOUP Zy Western Food Hui Ming Fishball Noodle Gourmet St (JB27) Sungei Road Laksa Ann Western Food 8 Plus Seafood Gourmet St (JB27) Theng Delights Feng Wei Delights Gourmet St (JB27) Yuet Sing -

Entree Beverages

Beverages Entree HOT/ COLD MOCKTAIL • Sambal Ikan Bilis Kacang $ 6 Spicy anchovies with peanuts $ 4.5 • Longing for Longan $ 7 • Teh Tarik longan, lychee jelly and lemon zest $ 4.5 • Kopi Tarik $ 7 • Spring Rolls $ 6.5 • Milo $ 4.5 • Rambutan Rocks rambutan, coconut jelly and rose syrup Vegetables wrapped in popia skin. (4 pieces) • Teh O $ 3.5 • Mango Madness $ 7 • Kopi O $ 3.5 mango, green apple and coconut jelly $ 6.5 • Tropical Crush $ 7 • Samosa pineapple, orange and lime zest Curry potato wrapped in popia skin. (5 pieces) COLD • Coconut Craze $ 7 coconut juice and pulp, with milk and vanilla ice cream • Satay $ 10 • 3 Layered Tea $ 6 black tea layered with palm sugar and Chicken or Beef skewers served with nasi impit (compressed rice), cucumber, evaporated milk onions and homemade peanut sauce. (4 sticks) • Root Beer Float $ 6 FRESH JUICE sarsaparilla with ice cream $ 10 $ 6 • Tauhu Sumbat • Soya Bean Cincau $5.5 • Apple Juice A popular street snack. Fresh crispy vegetables stuff in golden deep fried tofu. soya bean milk served with grass jelly • Orange Juice $ 6 • Teh O Ais Limau $ 5 • Carrot Juice $ 6 ice lemon tea $ 6 • Watermelon Juice $ 12 $ 5 • Kerabu Apple • freshAir Kelapa coconut juice Muda with pulp Crisp green apple salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with deep $ 5 fried chicken. • Sirap Bandung Muar rose syrup with milk and cream soda COFFEE $ 5 • Dinosaur Milo $ 12 malaysian favourite choco-malt drink • Beef Noodle Salad $ 4.5 Noodle salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with marinated beef. -

Download Map and Guide

Bukit Pasoh Telok Ayer Kreta Ayer CHINATOWN A Walking Guide Travel through 14 amazing stops to experience the best of Chinatown in 6 hours. A quick introduction to the neighbourhoods Kreta Ayer Kreta Ayer means “water cart” in Malay. It refers to ox-drawn carts that brought water to the district in the 19th and 20th centuries. The water was drawn from wells at Ann Siang Hill. Back in those days, this area was known for its clusters of teahouses and opera theatres, and the infamous brothels, gambling houses and opium dens that lined the streets. Much of its sordid history has been cleaned up. However, remnants of its vibrant past are still present – especially during festive periods like the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn celebrations. Telok Ayer Meaning “bay water” in Malay, Telok Ayer was at the shoreline where early immigrants disembarked from their long voyages. Designated a Chinese district by Stamford Raffles in 1822, this is the oldest neighbourhood in Chinatown. Covering Ann Siang and Club Street, this richly diverse area is packed with trendy bars and hipster cafés housed in beautifully conserved shophouses. Bukit Pasoh Located on a hill, Bukit Pasoh is lined with award-winning restaurants, boutique hotels, and conserved art deco shophouses. Once upon a time, earthen pots were produced here. Hence, its name – pasoh, which means pot in Malay. The most vibrant street in this area is Keong Saik Road – a former red-light district where gangs and vice once thrived. Today, it’s a hip enclave for stylish hotels, cool bars and great food. -

Food KL 1 / 100 Nasi Lemak

Food KL 1 / 100 Nasi Lemak ● Nasi Lemak is the national dish of Malaysia. The name (directly translated to ‘Fatty Rice’) derives from the rich flavours of the rice, which is infused in coconut milk and pandan. ● The rice is served with condiments such as a spicy sambal, deep fried anchovies and peanuts, plus slices of raw cucumbers and boiled eggs. Photo credit: http://seasiaeats.com/ Food KL 2 / 100 Food KL 3 / 100 Roti Canai ● Roti Canai is a local staple in the Mamak (Muslim Indian) cuisine. ● This flat bread is pastry-like and is somehow crispy, fluffy and chewy at the same time. ● It is usually served with dhal and different types of curries. Photo credit: http://kuali.com/ Food KL 4 / 100 Food KL 5 / 100 Teh Tarik ● There is nothing more comforting thnt a hot glass of sweet teh tarik (pulled tea). ● Black tea is mixed with condensed milk and “pulled” multiple times into frothy perfection. ● You can order it plain or ask for teh tarik halia, which has ginger. Photo credit: http://blog4foods.wordpress.com/ Food KL 6 / 100 Food KL 7 / 100 Ikan Bakar ● Directly translated to English, Ikan Bakar means burnt fish. ● Whole fish or sliced fish is slathered with a sambal or tumeric paste and is charcoal-grilled or barbequed (sometimes in a banana leaf wrap). ● It is often served with a soy-based dipping sauce that brings out the flavours even more. Food KL 8 / 100 Food KL 9 / 100 Banana Leaf Rice ● In traditional South Indian Cuisine, a meal is normally served on a banana leaf. -

Nipah Takeaway & Delivery Promo Order Form A4 Lowres

nipah takeaway, delivery and drive-through Explore the rich and diverse flavours of authentic Southeast Asian classics from Nipah. Choose from individual and family sets as well as hampers, cakes and cookies. order form INDIVIDUAL SETS HARI RAYA SETS | 12 MAY 2021 ONWARDS A: Nasi Minyak, Rendang Ayam Minang, Acar Buah, Lemang Nipah: Lemang and Ketupat, Kuah Kacang, Walnut Dates Cake, Imported Premium Dates Choice of Rendang Daging or Rendang Ayam Takeaway Packaging 48 Takeaway Packaging 48 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 B: Briyani Gam Kambing, Acar Rampai, Serewa Durian, Lontong Raya: Ketupat and Serunding, Kuah Lodeh, Imported Premium Dates Choice of Sambal Udang or Sambal Sotong Takeaway Packaging 48 Takeaway Packaging 48 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 C: Steamed Fragrant Jasmine Rice, Daging Salai Masak Pulut Kuning Raja: Pulut Kuning and Telur, Lemak Cili Padi, Acar Rampai, Pulut Hitam and Longan, Daging Masak Hitam Berempah, Choice of Kari Imported Premium Dates Ayam or Rendang Ayam Takeaway Packaging 48 Takeaway Packaging 48 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 128 FAMILY SETS A: Steamed Fragrant Jasmine Rice, Sambal Tumis Udang B: Briyani Gam Johor, Ayam Briyani, Sayur Jelatah, Galah, Gulai Lemak Cili Padi Daging Salai, Ayam Kari Acar Rampai, Serawa Durian, Imported Premium Dates Kapitan, Pecal Jawa, Acar Rampai, Serawa Nangka, Imported Premium Dates Takeaway Packaging 218 Takeaway Packaging 218 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 508 3-Tier Tiffin Carrier Set 508 -

MUIS HALAL CERTIFIED EATING ESTABLISHMENTS (1) Click on "Ctrl + F" to Search for the Name Or Address of the Establishment

Muis Halal Certified Eating Establishments NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE MUIS HALAL CERTIFIED EATING ESTABLISHMENTS (1) Click on "Ctrl + F" to search for the name or address of the establishment. (2) You are advised to check the displayed Halal certificate & ensure its validity before patronising any establishment. (3) For updates, please visit www.halal.sg. Alternatively, you can contact Muis at tel: 6359 1199 or email: [email protected] Last Updated: 7 Nov 2018 POSTAL COMPANY / EST. NAME ADDRESS CODE 126 CONNECTION BAKERY 45 OWEN ROAD 01-297 - 210045 13 MILES 596B SEMBAWANG ROAD - SEMBAWANG SPRINGS ESTATE 758455 149 Cafe @ TechnipFMC 149 GUL CIRCLE - - 629605 (Mngd By The Wok People) REPUBLIC POLYTECHNIC 1983 A Taste of Nanyang E1 WOODLANDS AVENUE 9 02 738964 (Food Court A) 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 2 Ang Mo Kio Drive 02-10 ITE College Central 567720 SINGAPORE MANAGEMENT 1983 A Taste of Nanyang 70 STAMFORD ROAD 01-21 178901 UNIVERSITY 1983 Cafe Nanyang 60 AIRPORT BOULEVARD 026-018-09 CHANGI AIRPORT TERMINAL 2 819643 HARBOURFRONT CENTRE, TRANSIT 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 MARITIME SQUARE 02-21 099253 AREA 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 Jurong East Street 21 01-01 Tower C, Jurong Community Hospital 609606 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE 02-32/33 FAIRPRICE HUB 629117 HARBOURFRONT CENTRE, TRANSIT 1983 Coffee & Toast 1 MARITIME SQUARE 02-21 099253 AREA 1983 Coffee & Toast 2 SIMEI STREET 3 01-09/10 CHANGI GENERAL HOSPITAL 529889 21 On Rajah 1 JALAN RAJAH 01 DAYS HOTEL 329133 4 Fingers Crispy Chicken 50 Jurong Gateway Road 01-15A JEM Shopping Mall 608549 4 Fingers -

Buffet Station Sta Station Dome

ELS SINAR SEMI-BUFFET DINNER Buffet Station MENU A HASIL KAMPUNG Ulam - ulaman, Sambal Belacan, Sambal Mangga, Sambal Gesek, Dome Set Assorted Dried Fish & Kerabu MAIN COURSE *Will be served on the table ROJAK BUAH White Rice Nasi Minyak Cucumber, Guava, Mango, Pineapple, Papaya, Ayam Masak Merah Pickled Mango, Papaya & Guava Sotong Goreng Kunyit Lamb Curry ROJAK MAMAK Ikan Masak Kicap Fried Beancurd, Fried Tempe, Fried Hard-boiled Egg, Fried Fish Cake, Dalcha Fried Vegetables Fritters with Homemade Peanut Sauce ANEKA KEROPOK Sta Station Belinjau Crackers, Vegetables Crackers & Papadum MURTABAK SOUP Chicken and Beef Mini Murtabak - Served with Pickled Onion & Vegetable Dalcha Bubur Lambuk CHAI TOW KWAY Sup Berempah (Beef, Chicken & Lamb) Stir-fried Carrot Cake with Chili Paste, Eggs, Dark Sweet Soy Sauce, Salted Vegetables, *Selection of Noodles - Yellow Noodles, Flat Noodles or Rice Vermicelli Beansprout, Spring Onion & Fried Onion Served with Condiments IKAN BAKAR DESSERTS Sea Bass Fillet, Cencaru and Keli - Served with Air Asam & Sambal Kicap Kurma, Pengat, Sago Gula Melaka, Tradisional Kuih Muih Melayu, Agar - agar Buah, Bread Butter Pudding with Vanilla Sauce, Sliced Cake, Local Fruits & Assorted Biscuits KAMBING PANGGANG Served with Mint Sauce & Black Pepper Sauce ICE CREAM GORENG - GORENGAN DRINKS Banana, Sweet Potato, Anchovies Fritters, Spring Rolls & Keropok Lekor Sirap Selasih, Air Jagung, Teh Tarik & Kopi SATAY AYAM & DAGING Served with Peanut Sauce, Cucumber & Onions FRIED NOODLES ELS SINAR SEMI-BUFFET DINNER Buffet Station -

The Local Globetrotters Kuala Lumpur Trot Fact Sheet: 1

The Local Globetrotters Kuala Lumpur Trot Fact Sheet: Insider Tips on What to Do, Eat and Drink in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 1 Eat at a “Mamak” Restaurant There are lots of Mamak restaurants in KL, and most will offer a pretty standard menu. Here is a helpful list of popular mamaks in the KL area. From that list my favorite is Roti Tissue Devi’s Corner, located in Bangsar on the busy Jalan Telawi 3 (note: Jalan means street in Malay). There is a night market Maggi Goreng (or “pasar malam”) located next to the Bangsar mosque every Sunday night from 6pm onwards that is worth checking out for more street food! You will be able to see the mosque from Devi’s Corner. Must tries at the Mamak include: “Maggi Goreng” (essentially stir fried ramen noodles), with your choice of protein. Add a fried egg on top <3 Roti Canai: Arguably the most ordered snack/dish at the Nasi Kandar Roti Canai Teh Tarik mamak, this is a kind of flatbread similar to the Indian paratha. Served with fish curry (but you can request for chicken or beef too), and dhal (lentil curry). Roti Tissue (an almost paper thin, crispier and sweet Eat, Eat and Eat! version of the roti canai). It’s pretty big (see picture on Eating is the Malaysian national pastime. Thanks to the hot and humid weather, air- right, so share with friends!) conditioned malls are always packed with throngs of Malaysians who window shop or Nasi Kandar: White rice with curry poured over the rice watch a movie at the cinema, and of course eat at the many restaurants and cafes that (the curry blend and flavor is what differentiates this dish from one place to another), served with fried chicken, fish, make up a significant portion of any mall. -

Takeaway & Delivery Brochure

TAKEAWAYS We are observing the highest standards of health and safety in accordance with Marriott International’s Global Food Safety Standards so that you can enjoy your meal with complete peace of mind. & DELIVERIES The food is prepared with utmost care following recommended measures on appropriate hygiene levels. All our associates are wearing face masks and gloves while handling your food from all stages of cooking till delivery. All associates are disinfecting and washing their hands at regular intervals as per Marriott International’s Global Food Safety Standards. Our associates are undergoing constant temperature checks to ensure maximum precaution. Contact tracing information and body temperature recordings published on all takeaway containers. The hotel has enforced elevated precautionary operational protocols and heightened sanitation practices including deep-cleaning measures in all areas. CALL OR WHATSAPP 012-507-3327 TO ORDER FLIP TO VIEW MENU FAMILY FEASTS FAMILY FEASTS 20% OFF CHICKEN RM158 RM126.40 Bak Kwa Crusted Mandarin Chicken Wok Fried Medley Vegetables Garlic Mashed Potatoes Cameron Highlands Spring Mix Salad Sarawak Black Peppercorn Au Jus and Golden Tangy Apricot Sauce Salted Caramel Chocolate Fudge 15% OFF FISH RM168 RM142.80 Deep Fried Whole Seabass with Spicy Cantonese Black Bean Sauce Wok Fried French Beans and Shiitake Mushrooms XO Fried Rice Cameron Highlands Spring Mix Salad Lemon Vinaigrette Salted Caramel Chocolate Fudge 10% OFF LAMB RM178 RM160.20 Char Siew Dorper Lamb Rack Pineapple Fried Rice Poached -

Bbq Buffet Dinner Menu 1

BBQ BUFFET DINNER MENU 1 Fresh Garden Salad Assortment of Leaf Lettuce- Butter Lettuce, Yellow Frieze, Ice Berg Lettuce, Lolo- Rosso, Sliced Onion, Grated Carrot, Cherry Tomato, Cucumber, Black Olive, Red Cabbage, Mix -Capsicum Corn Oil Dressing, Sea Salt and Cracked Pepper 1000 island, French Dressing and Olive Oil Dressing Caesar Salad with Condiment Caesar Dressing, Anchovies, Croutons, Crispy Beef Bacon and Parmesan Cheese Canapé’s Miniature Open Face Sandwich Tomato Bruchetta Thai Glass Noodles in Cup Roasted Beef Roll with Mustard Sauce Soup Cream of Pumpkin Soup Bread Counter Assorted Bread Roll and Loaf, Rye Bread Butter & Olive oil From The Grill Grilled Chicken Sausages, Grilled Lamb Shoulder, Grill Black Mussel Grill Crab Flower, Grill Chicken, Vegetables Skewer, Corn on The Cob, Fish in Banana Leaf, Mini Steak Beef From The Sauce Counter Black Pepper Sauce, Brazilian BBQ Sauce, Mint sauce, Rosemary Sauce, Air Assam, Chili Kicap, Mustard Sauce Action Stall 1 Satay with Condiment Chicken Satay, Beef Satay, Onion, Cucumber, Pressed Rice, Peanut Sauce Stall 2 Roti John with Condiment Loaf Bread, Minced Chicken, Egg, Onion, Tomato, Cabbage Stall 3 Penang Char Kway Teow Prawn, Cockles Meat, Bean Sprout, Chive & Egg Stall 4 Lok Lok with Condiment Chee Cheong Fun, Prawn Ball, Fish Ball, Bean Curd Skin, Crab Ball, Lobster Ball, Crab Stick, Kangkung, Seafood Bean Curd, Quill Egg Sauce Peanut Sauce, Chili Sauce, Sweet Sauce Stall 5 Asam Laksa with Condiment Rice Noodle, Onion, Cucumber, Pineapple, Mint Leaf, Chili, Hard Boiled Egg, Prawn -

Signature Cocktails Ubud Tiki

SIGNATURE COCKTAILS But, First, Cocktails… Frozen Basil Madu (sour) 130 The Rujak (light/spicy) 130 local lemon basil leafs, Arak muddled with blossom chili infused vodka, lemongrass, passion fruit, honey and lime tamarind syrup, cucumber, mango, kaffir lime Star Fruit Sangria (sweet) 130 Mango-Mint-Arita (sweet/fruity) 130 white wine, star fruit, dash of gin, lime, ginger ale, gin, mango, lime, mint, ginger ale Tangerine & Clove Margarita (sweet/sour) 130 Loloh Bali (herbaceous) 130 clove infused tequila, tangerine, lime, Cointreau, gin, kemangi (local lemon basil), mint, turmeric, blossom honey rosemary, lemongrass, lime, lemongrass syrup UBUD TIKI BAR It’s Time to Rumble in the Jungle! The Angry Ubudian 135 140 Bali Saz-Arak chili infused vodka, fresh mango, mango syrup, local Balinese arak, whisky, rosemary, lime juice, club soda kemangi basil, simple syrup, lime juice (sweet/refreshing) (smoky/strong) Plantation Punch 135 140 Sumatra Kula rum, pineapple juice, lime juice, orange blended light rum, triple sec, tangerine juice, grenadine syrup juice, lime juice, honey syrup (fruity/light) (sweet) Rumble In The Jungle light rum, crème de cacao, coconut milk, kaffir lime, ginger, lemon grass, chili, syrup (sweet/creamy/rich) 150 Prices are in thousand Rupiah and subject to 21% tax and service charge. CLASSIC COCKTAILS Nothing a Cocktail can’t fix, please let us know your preference Caipiroska (sweet/sour) 120 Negroni (bitter) 130 vodka, lime juice, syrup gin, Campari, vermouth Pina Colada (sweet) 120 Margarita (sour) 130 rum, coconut -

7218-SHAZ-MITEC-11-2019 RAYA LATEST Copy

AIDILFITRI INDULGENCE RM PER 138 PERSON Selera Kita | Appetizer Noodle Station Popiah Basah | Wet Spring Skin wrapped with Vegetables Serve with Laksa Johor | Johorean Coconut Spicy Fish Broth serve with Spaghetti and Condiment Red and Black Sweet Sauce Asam Laksa | Tamarind Broth with Minced Fish serve with Rice Noodle and condiment Tauhu Sumbat | Stuing Bean Curd Vegetables Served with Peanut Sauce Laksam | Kelantanese Rice Noodle serve with Coconut and Condiment Acar Nyonya | Carrot, Cucumber cooked with Sweet and Spicy Sauce Acar Buah | Pickles Mixed Fruits Cooked with Palm Sugar Rice Counter Rojak Buah-Buahaan | Local Mixed Fruits Served with Shrimps Black Sauce Nasi Minyak bersama Rendang Toki | Berasmathi Cooked with Ghee and Bergedil Ayam | Deep Fried Potatoes and Chicken Minced Dumpling Butter served with Beef Rendang Toki Gado-Gado | Local Vegetables Served with Peanut Sauce Nasi Dagang Bersama Kari Ikan Tongkol | Rice Cooked with Herb serve with Tuna Curry Gravy Ulam-ulam kampong | Raw vegetables & Malay herb leave Ketupat Palas | Stimmed Glutinous Rice Wrapped with Palas Leaf Santapan Utama | Hot dished Lemang | Glutinous Rice Cooked with Bamboo Lontong Bersama Dengan Kuah Lodeh | Rice Cube Served with Coconut Ketupat | Braised Coconut Leave Stuing with Rice Vegetables Gravy Rendang Ayam Masak Padang | Slow Cooked Chicken with Turmeric Concentrated Semestinye Ada Bersama | Accompaniment Coconut Herb and Spiced Dalca Johor | Mixed Vegetables with Lentil Cooked with Curry Paste Johor Style Serunding daging | Beef floss Ikan