1 Toward a Spatial History in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Mythos Israel Israel Dr

60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Israel = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung Dr. Viktoria Waltz, München 9.12.09 60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Mythos Israel Israel Dr. Viktoria Waltz 9.12.09 = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung 0. Ausgangssituation und Probleme der Neugründung 15. Mai 1948 zionistische Kolonien, palästinensische Orte Bevölkerungsverteilung Bodeneigentum Machtverhältnisse 1. Verfassung und Bürgerrechte 2. Einwanderung und Ansiedlung von Immigranten 3. Raumplanung Landenteignung Organe und Planungen Nationalplan 1950 Kibbuzim und Moshavim New Towns (Beispiele Kiryat Gad, Ashkelon, Ramleh, Jaffa) Wasser, Parks Planungssystem Kartenübersicht UN-Teilung 1947 Topographie und Lage ‚Tourismus„-Karte, 56,7% ‚‚jewish„ nach 1948 (70%„ jewish„) - mit ‚Golan„ (100%?) Letzte Phase vor der Staatsgründung 1948 Kolonien 1945 Palästinensische Dörfer und Städte Die Utopie von 1945 einem ‚leeren Land‘ 1948 Lage des bis 1946 durch den JNF gekauften Landes Quellen: Grannott 1956, Richter 1969, Waltz/Zschiesche 1986 Situation 14. May 1948 im Staatsgebiet Israel • Jüdische Seite Palästinensische Seite ca. 700.000 EW, davon ca. 156.000 EW, und ca. 330.812 ca. 50% Geflohene 750.000 Vertriebene (Nakba) aus Europa (Faschismus) Konzentriert mit 90% im Konzentriert mit 80% in den Inneren des Landes: Küstenstädten zwischen: - Negev (Beduinen) - Tel Aviv und - ‚Dreieck„ um Um el Fahem - Haifa - Galiläa mit Nazareth Als jüdische Mehrheit -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

Kit Important Information About Tel-Aviv, the University, and Student Life

Welcome Kit Important Information about Tel-Aviv, the University, and Student Life 1 Contents Greetings from the Student Life Team (Madrichim) .................................................................. 3 How can you contact us?........................................................................................................ 3 Let’s sync our timetables! ...................................................................................................... 3 Important Telephone Numbers and Information ...................................................................... 4 External Telephone Numbers ................................................................................................. 4 Helpful TAU Extensions .......................................................................................................... 4 Wi-fi on campus ...................................................................................................................... 4 Mobile Phones ............................................................................................................................ 5 Information for Dormitory Residents ......................................................................................... 7 Rules and regulations for dorms residents ............................................................................ 7 Services in the Dorms ............................................................................................................. 8 Safety, Health and Security Services ....................................................................................... -

Fifty Years of High-Rise Building in Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Public Assets vs. Public Interest: Fifty Years of High-rise Building in Tel Aviv-Jaffa Talia Margalit* Ben Gurion University of the Negev In order to provide for public needs authorities collect capital assets and sustain fixed assets that house spatial facilities and infrastructure. However, as structural and urban regime scholars showed, this inherently compromises public interest, while authority’s enslavement to capital increases social strata and limits develop- ment to market lines. In addition, these problems increased substantially since the cutbacks in national provision to cities in the late 1970s, as the rise of entre- preneurial urban regimes and the activation of conservative Post-Keynesian poli- cies took hold. Accordingly, the main compromising planning practices found in the new era are ad-hoc flexible planning regulations, luxurious building projects and large-scale privatization of fix public assets. Planning deals that pack these practices together are the data of this article, but they were found as continuous planning convention in a tracing of the high-rise building activity in Tel Aviv- Jaffa since the 1950s. The consistency of privatization acts is related to the mere existence of many publicly owned lots in the city, yet this affluence does not ex- plain the long-time compromising usage of such assets. For explanation, the article dwells on the subject of continuity and evolution in practice through structural periods, by readdressing urban regime principals as portrayed by Clarence Stone and hegemonic accumulation strategy as defined by Bob Jessop. Keywords: Public Interest, Urban Politics, Planning Deals, Periodization and Continuity, Local Conventions, Hegemony. Long-term planning conventions that link urban growth with compromises to pub- lic interest are reveale when tracing the history of the wide spread peaks of Tel- Aviv’s skyline. -

Handbook for Study Abroad and Short Term Programs

TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL Study Abroad, Short Term & Student Exchange Programs Pre-Departure Handbook 2021-2022 Tel Aviv University International Carter Building, Room 108, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel Tel: +972-3-640-8118 Fax: +972-3-6409582 www.international.tau.ac.il WELCOME FROM THE DIRECTOR OF TAU INTERNATIONAL We congratulate you on your admission to Tel Aviv University International. Soon, you will become a part of the Tel Aviv University family, which boasts a highly acclaimed faculty, a top-tier student body, and international prestige. Whether you are coming for a Short Term Program, a Study Abroad Semester or Year, an Exchange Program, or you are here conducting Independent Research, you will join other students from all over the world to embark on a unique personal and academic journey. Your experience will surely prove both challenging and rewarding. Tel Aviv University International is here to help you get acclimated to your new environment and complement your academic experience with an array of services and activities. We invite you to take full advantage of the unique opportunity to live in Tel Aviv, the epicenter of Israeli culture. Being a part of the largest university in Israel allows you to enjoy the many state-of-the-art facilities and a variety of social and athletic clubs on campus. Our dedicated staff in the USA, Canada, and on campus (us included), are here to accompany and support you on your journey. We want to make sure that you have a rewarding and enjoyable experience during your stay with us at Tel Aviv University and hope to create a life-long connection with you! With warmest regards, Ms. -

Demolishing PEACE HOUSES DEMOLITIONS in East Jerusalem 2000 - 2010

Dr. Meir Margalit DEMOLISHING PEACE HOUSES DEMOLITIONS IN EAST JERUSALEM 2000 - 2010 International Peace and Cooperation Center 2014 This publication has been produced with the support of Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the view of Friedrich Ebert Stiftung A publication by the International Peace nternational and Cooperation Center 2014 eace ooperation PO Box 24162, Jerusalem 91240 enter T +972 2 5811992 F +972 2 5400522 [email protected], www.ipcc-jerusalem.org CONTENTS Introduction...............................................................................9 Chapter 1 Demolition Data: Orders and Executions . 23 Chapter 2 Discrimination in the execution of demolition orders . 55 Chapter 3 The rational for illegal construction . 69 Chapter 4 The motives underlying municipality demolition policies . 103 Chapter 5 Legal tools for executing the demolitions . 119 Chapter 6 The apparatus for executing demolitions . 137 Chapter 7 The system that enables demolitions . 151 Chapter 8 The non-formal apparatus .............................................167 Chapter 9 The approach of the legal system to building violations in East Jerusalem ......................................................181 Chapter 10 Final remarks ...........................................................193 Selected References .................................................................195 TABLES Table 1.1 House demolitions in East Jerusalem since 1992 .....................24 Table 1.2 Data for administrative -

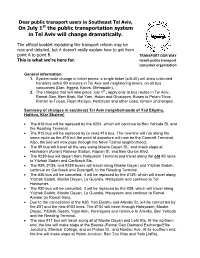

On July 1St the Public Transportation System in Tel Aviv Will Change Dramatically

Dear public transport users in Southeast Tel Aviv, On July 1st the public transportation system in Tel Aviv will change dramatically. The official booklet explaining the transport reform may be nice and detailed, but it doesn't really explain how to get from point A to point B. TRANSPORT OUR WAY This is what we're here for. Israeli public transport consumer organization General information: 1. System-wide change in ticket prices: a single ticket (₪6.40) will allow unlimited transfers within 90 minutes in Tel Aviv and neighboring towns, on all bus companies (Dan, Egged, Kavim, Metropolin). 2. The changes that will take place July 1st , apply only to bus routes in Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan, Beni Brak, Bat Yam, Holon and Givatayim. Buses to Petah-Tikva, Rishon le-Tziyon, Rosh Ha’ayin, Hertzliyah and other cities, remain unchanged. Summary of changes in southeast Tel Aviv (neighborhoods of Yad Eliyahu, Hatikva, Kfar Shalem) The #16 bus will be replaced by the #204, which will continue to Ben Yehuda St. and the Reading Terminal. The #15 bus will be replaced by (a new) #16 bus. The new line will run along the same route as the #15 but the point of departure will now be the Carmelit Terminal. Also, the line will now pass through the Neve Tzahal neighborhood. The #9 bus will travel all the way along Moshe Dayan St., and make stops at Hashalom (Azrieli) Railway Station, Kaplan St. and Ben Gurion Blvd. The #239 bus will depart from Hatayasim Terminal and travel along the old #9 route to Yitzhak Sadeh and Carlibach Sts. -

Housing Distress in Jaffa

Executive Summary This position paper is the result of collaboration between the non-profit organization BIMKOM - Planners for Planning Rights, the Technion Laboratory for Planning with the Community, and the People of Jaffa's Committee for the Preservation of Rights to Land and Housing. The report investigates the story of a major wave of eviction and demolition orders facing nearly five hundred homes in Jaffa. Most of these homes are ‘absentee ownership’ properties, administered through a Government body set up to manage the homes of Palestinians who were no longer living in the country after the 1948 war. Today the homes are occupied by mostly Palestinian Israeli families, under a ‘protected tenancy’ agreement. When we began researching the situation in January 2008, the People of Jaffa's Committee was leading a determined public campaign for tenants’ rights against the eviction and demolition orders, and was providing legal aid for families who needed immediate aid. We found that Palestinian citizens in Jaffa face many and varied housing problems. This report focuses on only one aspect of the problem, that of protected tenants in absentee ownership (AO) proprieties. Our goal was to investigate the background for the wave of eviction and demolition orders, with a particular focus on the urban planning aspects, in order to make recommendations for change. We ask four main questions: 1. Why have so many eviction orders been issued? 2. What is the responsibility of the Israel Lands Administration (ILA) and the Municipality of Tel Aviv-Jaffa? Can they freeze the evictions, and do they have the authority to enact solutions? 3. -

Is Empowerment of Disadvantaged Populations Achievable Through Housing Policies? a Study of the Impact of Social Housing on the Empowerment of the Poor in Israel”

“Is Empowerment of Disadvantaged Populations Achievable through Housing Policies? A Study of the Impact of Social Housing on the Empowerment of the Poor in Israel” Guy Doron London School of Economics and Political Sciences Resubmitting with corrections Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD January 2015 Contents Abstract 1 List of Tables 3 List of Figures 5 List of Illustrations 6 PART 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 8 1.1 Overview 8 1.2 Israel as a unique case 11 1.2.1 Dominance of central government 11 1.2.2 The political system 11 1.2.3 Dominance of security issues on the political agenda 12 1.2.4 Ethnicity 12 1.3 Summary of chapters 13 1.3.1 Chapter two 13 1.3.2 Chapter three 14 1.3.3 Chapter four 14 1.3.4 Chapter five 15 1.3.5 Chapter six 15 1.3.6 Chapter seven 16 1.3.7 Chapter eight 16 1.3.8 Chapter nine 17 Chapter 2 A Review of the Literature on Empowerment 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Perspectives on empowerment and housing policy 20 2.2.1 The disadvantaged 22 2 2.2.2 Poverty 23 2.2.3 Localisation 25 2.3 Measuring individual participation 29 2.3.1 Arnstein’s ladder of participation 30 2.3.2 The literature on participation 33 2.3.3 The literature on mobility 34 2.4 Collective empowerment and public policy 36 2.4.1 Collective empowerment 37 2.4.2 Collective empowerment in housing policy 40 2.4.3 Pressure groups 43 2.5 Providing tools in practice: training schemes 45 2.5.1 Knowledge gaps 46 2.5.2 Training in practice 47 2.6 Multi-conflict societies 51 2.7 Limitations 53 2.8 Summary and conclusions 56 Chapter 3 History: The Chronology of the Housing System in Israel 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2. -

Israel Atomic Energy Commission I S R a E L M E T E O R O L O G I C a L S

USE OF GASEOUS TRACEBi FOR AIR POLLUTION STUDIES IN URBAN AREAS J. BINENBOYM, I. GILATH, M. MEUZER, CH. GILATH. A. LEVIN, M. RINDSBERGER. and A. MANES Report to the National Council for Research and Development Israel Atomic Energy Commission and Israel Meteorological Service 19 7 5 USE UK GASEOUS 1.:ACERS FOR AIR POLLUTION STUDIES IN URBAN AREAS J. Binenboym and T. Gilath Inorganic and Physical Chemistry Dept. Soreq Nuclear Research Centre M. Meltzer, Ch. Gilath and A. Levin Isotope Applications De.pt. Poreq Nuclear Research Centre M. Rindsberger and A. Manes Israel Meteorological Service Beit Dagan Report to the National Council for Research and Development Soreq Nuclear Research Centre Israel Meteorological Service Israel Atomic Energy Commission Ministry of Transportation August, 1975 I.:ONTI:NTS 1 . INTRODUCTION 3 2. METHODOLOGY 6 3. MODELS FOR THE COMPUTATION OF DISPERSION OF POLLUTANTS EMITTED BY POWER PLANT STACKS 8 4. EXPERIMENTAL 11 4.1 Analytical 11 4.2 Tracer injection and sampling 13 4.3 Field experiments 14 5. RESULTS 16 6. ERROR ANALYSIS 18 7. DISCUSSION 21 8. CONCLUSIONS 28 APPENDIX 31 REFERENCES 33 TABLES 35 FIGURES 49 - 1 - AJ.SlKAi i A tracer technique, using the inert gas SF , was apolied to determine the dispersion of the stack el fluents frcm the Reading povcr plant, ur.i.., -.-' '), In the greater Tel-Avi\ ire,i. The contribution :--i the power plant to ground level concentratic .s of S0? was assessed by comparing the measured SO., values with t'nse calculated from the SF, dilution and the SO., emission concentration. It is shown that at some measuring stations the ground level SO, concentrations are greatly enhanced from sources other than the power plant. -

TEL AVIV-YAFO Zum Problem Des Einflusses Heterogener

Helmut Ruppert: Tel Aviv-Yafo 31 TEL AVIV-YAFO Zum Problem des Einflusses heterogener Einwanderergruppen auf Stadtstruktur und Stadtentwicklung Mit 5 Abbildungen, 1Beilage (I) und 1Tabelle Helmut Ruppert The waves of into Pales von den unter Summary: Jewish immigration judischen Einwanderorganisationen tine and Israel have been characterised by their distinctive stiitzt. af areas of From the cultural, composition regards origin. Bedingt durch politische und wirtschaftliche Gege economic and social heterogeneity of the Jewish immi benheiten lafit sich daher fiir jede Zeitperiode der Ein grants, an influence on spatial group behaviour would be wanderung, einer sogenannten Aliya1), eine charakte expected. The temporal-spatial impact of the immigrant ristische landsmannschaftliche fest groups was investigated using the example of the structure Zusammensetzung die in ihrer and development of the city of Tel Aviv-Yafo. stellen, Wirkung auf die Stadtentwicklung Starting from the traditional elements of the oriental Tel Aviv-Yafos untersucht werden soil. levantine city of Jaffa, the influence of Russian and Polish Die im zeitlichen Nacheinander angelegten Stadt on the and structure of Tel Aviv in the - emigrants founding viertel Tel Aviv-Yafos lassen bedingt durch die kul years 1909-1931 is described. The waves of central Euro turelle, wirtschaftliche und soziale Heterogenitat der in the 1932 pean Jewish immigrants into Palestine years zu - verschiedenen Zeiten eingewanderten Juden einen 1938 gave dynamic impetus to the economic and cultural Einflufi des auf den Raum erwar of the in the Gruppenverhaltens development city. Vigorous growth tertiary ten.Die sector made Tel Aviv into the main urban centre of Pales Untersuchung iiber die Bedeutung heterogener tine.