Fifty Years of High-Rise Building in Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Rates, Indications, and Speech Perception Outcomes of Revision Cochlear Implantations Doron Sagiv 1,2,*,†,‡, Yifat Yaar-Soffer 3,4,‡, Ziva Yakir 3, Yael Henkin 3,4 and Yisgav Shapira 1,2 1 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] 2 Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel 3 Hearing, Speech, and Language Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 5262100, Israel; [email protected] (Y.Y.-S.); [email protected] (Z.Y.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 4 Department of Communication Disorders, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv City 6997801, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-35-302-242; Fax: +972-35-305-387 † Present address: Department of Oolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA. ‡ Sagiv and Yaar-Soffer contributed equally to this study and should be considered joint first author. Abstract: Revision cochlear implant (RCI) is a growing burden on cochlear implant programs. While reports on RCI rate are frequent, outcome measures are limited. The objectives of the current study were to: (1) evaluate RCI rate, (2) classify indications, (3) delineate the pre-RCI clinical course, and (4) measure surgical and speech perception outcomes, in a large cohort of patients implanted in a tertiary referral center between 1989–2018. Retrospective data review was performed and included patient demographics, medical records, and audiologic outcomes. Results indicated that RCI rate Citation: Sagiv, D.; Yaar-Soffer, Y.; was 11.7% (172/1465), with a trend of increased RCI load over the years. -

Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery

1 In loving memory of my mother, Batsheva Friedman Stepansky, whose forefathers arrived in Zefat and Tiberias 200 years ago and are buried in their ancient cemeteries Zefat, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E. Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery Yosef Stepansky, Zefat Introduction In recent years a large concentration of gravestones bearing Hebrew epitaphs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries C.E. has been exposed in the ancient cemetery of Zefat, among them the gravestones of prominent Rabbis, Torah Academy and community leaders, well-known women (such as Rachel Ha-Ashkenazit Iberlin and Donia Reyna, the sister of Rabbi Chaim Vital), the disciples of Rabbi Isaac Luria ("Ha-ARI"), as well as several until-now unknown personalities. Some of the gravestones are of famous Rabbis and personalities whose bones were brought to Israel from abroad, several of which belong to the well-known Nassi and Benvenisti families, possibly relatives of Dona Gracia. To date (2018) some fifty gravestones (some only partially preserved) have been exposed, and that is so far the largest group of ancient Hebrew epitaphs that may be observed insitu at one site in Israel. Stylistically similar epitaphs can be found in the Jewish cemeteries in Istanbul (Kushta) and Salonika, the two largest and most important Jewish centers in the Ottoman Empire during that time. Fig. 1: The ancient cemetery in Zefat, general view, facing north; the bottom of the picture is the southern, most ancient part of the cemetery. 2 Since 2010 the southernmost part of the old cemetery of Zefat (Fig. 1; map ref. 24615/76365), seemingly the most ancient part of the cemetery, has been scrutinized in order to document and organize the information inscribed on the oldest of the gravestones found in this area, in wake of and parallel with cleaning-up and preservation work conducted in this area under the auspices of the Zefat religious council. -

TEL AVIV-YAFO 341 Sister — Snowski

TEL AVIV-YAFO 341 Sister — Snowski Sister Dr Moshe 68 Ussishkin. 44 01 90 Skcwronek Jacob Slonim Yigal Advct 53 Reines. .23 57 34 Smilar Shelomo I Derech Haifa.22 57 52 Sitman Mordechai Pattern Wkshp 13 Habanim R'G 72 89 32 Slonim Yitzhak 26 Gordon . 22 16 13 Smilg Moses 65 Frishman 22 73 04 128 Giborei Yisrael 3 17 52 Skubatz Samuel (Bldg Contr) & Bronia Res 37 Balfour 61 25 62 Smilovici Albert Advct Siton Leon Rstnt Ankara 8 Arlosoroff Holon 84 87 05 Slonim Yitzhak Ins Agt 6 Ahuzat Bayit 5 31 69 13 Akiva Arye 5 93 70 Skubelski Szaja Cafe-Tnuva I Derech P-T 62 17 56 Smilovitch Sam 35a Hayarkon.. .5 95 88 Sitronenbaum Jakob David Grocery Res 21 Yehonathan R"G . .72 79 33 205 Dizengoff 22 08 55 SMILOVITZ MIRIAM LADIES' 26 Haroeh R"G 72 88 63 Skula Milka & Baruch Slonim Zvi FASHIONS 45 Ben Yehuda.23 56 91 Sitruk Sion 14 Carmeli Ramat Hen 3 61 60 10 Yehuda Halevi B"B 72 79 82 Smilowitz Sylvia Broker's 22 Jabotinsky Holon 84 62 49 Skulnik & Zwas Chldn Clthng Slonimski S 5 Achiezer 3 13 18 59 Hayarkon 5 88 05 Sitshin Zeev Grocery 53 Ben Yehuda 22 79 96 Slonimsky Israel Smiltiner I 28 Shivat Zion 82 40 67 34 Shalom Aleichem 22 57 54 Skulnik Aharon Embroidery 33 Reading Ramat Aviv 44 50 74 Smiltiner S Sitt Bros Ladies' Dresses 20 Tchernichovsky 23 26 02 Slor Mordechai Advct 2 Rotberg Givatayim 73 16 68 69 Allenby 62 30 55 Skulsky Shelomo 31 Sederot Rothschild 62 12 30 Smith Shulamith Shikun Ledugma 22 SArmcnim R"G 72 27 53 Sitt Mazal & Jacob 19 Allenby . -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

On July 1St the Public Transportation System in Tel Aviv Will Change Dramatically

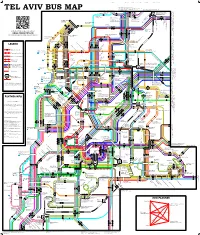

Dear residents of Ramat Aviv and Tel Aviv University students, On July 1st the public transportation system in Tel Aviv will change dramatically. The official booklet explaining the transport reform may be nice and detailed, but it doesn't really explain how to get from TRANSPORT OUR WAY point A to point B. Israeli public transport This is what we're here for. consumer organization General information: 1. System-wide change in ticket prices: a single ticket (₪6.40) will allow unlimited transfers within 90 minutes in Tel Aviv and neighboring towns, on all bus companies (Dan, Egged, Kavim, Metropolin). 2. The changes that will take place July 1st , apply only to bus routes in Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan, Beni Brak, Bat Yam, Holon and Givatayim. Buses to Petah-Tikva, Rishon le-Tziyon, Rosh Ha’ayin, Hertzliyah and other cities, remain unchanged. Summary of changes in Ramat Aviv, Azorey Hen, Kiryat Chinuch, Afeka, Neve Avivim and to/from Tel Aviv University The #27, #29, #45, #74 and #86 bus lines will be cancelled. They will be replaced by the following buses, to Tel Aviv and Holon: o #171: Azorey Hen, Kakal Blvd., Haim Levanon, Einstein, Brodetzky, Arlozorov (Merkaz/Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, Ha-hagana Railway Station, and then continuing to Holon on a route similar to the #173. o #271: Kalachkin Terminal, Klauzner, George Wise, Arlozorov (Merkaz / Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, and then continuing to Holon .אon the same route as the #74 o #71: Kiryat Chinuch, Levi Eshkol Blvd., Arlozorov (Merkaz / Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, and then continuing to Holon on a route similar to the #73. -

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Mythos Israel Israel Dr

60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Israel = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung Dr. Viktoria Waltz, München 9.12.09 60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Mythos Israel Israel Dr. Viktoria Waltz 9.12.09 = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung 0. Ausgangssituation und Probleme der Neugründung 15. Mai 1948 zionistische Kolonien, palästinensische Orte Bevölkerungsverteilung Bodeneigentum Machtverhältnisse 1. Verfassung und Bürgerrechte 2. Einwanderung und Ansiedlung von Immigranten 3. Raumplanung Landenteignung Organe und Planungen Nationalplan 1950 Kibbuzim und Moshavim New Towns (Beispiele Kiryat Gad, Ashkelon, Ramleh, Jaffa) Wasser, Parks Planungssystem Kartenübersicht UN-Teilung 1947 Topographie und Lage ‚Tourismus„-Karte, 56,7% ‚‚jewish„ nach 1948 (70%„ jewish„) - mit ‚Golan„ (100%?) Letzte Phase vor der Staatsgründung 1948 Kolonien 1945 Palästinensische Dörfer und Städte Die Utopie von 1945 einem ‚leeren Land‘ 1948 Lage des bis 1946 durch den JNF gekauften Landes Quellen: Grannott 1956, Richter 1969, Waltz/Zschiesche 1986 Situation 14. May 1948 im Staatsgebiet Israel • Jüdische Seite Palästinensische Seite ca. 700.000 EW, davon ca. 156.000 EW, und ca. 330.812 ca. 50% Geflohene 750.000 Vertriebene (Nakba) aus Europa (Faschismus) Konzentriert mit 90% im Konzentriert mit 80% in den Inneren des Landes: Küstenstädten zwischen: - Negev (Beduinen) - Tel Aviv und - ‚Dreieck„ um Um el Fahem - Haifa - Galiläa mit Nazareth Als jüdische Mehrheit -

Izraelský Kaleidoskop

Kaleidoscope of Israel Notes from a travel log Jitka Radkovičová - Tiki 1 Contents Autumn 2013 3 Maud Michal Beer 6 Amira Stern (Jabotinsky Institute), Tel Aviv 7 Yael Diamant (Beit ‑Haedut), Nir Galim 9 Tel Aviv and other places 11 Muzeum Etzel 13 Intermezzo 14 Chava a Max Livni, Kiryat Ti’von 14 Kfar Hamakabi 16 Beit She’arim 18 Alexander Zaid 19 Neot Mordechai 21 Eva Adorian, Ma’ayan Zvi 24 End of the first phase 25 Spring 2014 26 Jabotinsky Institute for the second time 27 Shoshana Zachor, Kfar Saba 28 Maud Michal Beer for the second time 31 Masada, Brit Trumpeldor 32 Etzel Museum, Irgun Zvai Leumi Muzeum, Tel Aviv 34 Kvutsat Yavne and Beit ‑Haedut 37 Ruth Bondy, Ramat Gan 39 Kiryat Tiv’on again 41 Kfar Ruppin (Ruppin’s village) 43 Intermezzo — Searching for Rudolf Menzeles (aka Mysteries remains even after seventy years) 47 Neot Mordechai for the second time 49 Yet again Eva Adorian, Ma’ayan Zvi and Ramat ha ‑Nadiv 51 Věra Jakubovič, Sde Nehemia — or Cross the Jordan 53 Tel Hai 54 Petr Erben, Ashkelon 56 Conclusion 58 2 Autumn 2013 Here we come. I am at the check ‑in area at the Prague airport and I am praying pleadingly. I have heard so many stories about the tough boys from El Al who question those who fly to Israel that I expect nothing less than torture. It is true that the tough boy seemed quite surprised when I simply told him I am going to look for evidence concerning pre ‑war Czechoslovak scout Jews in Israeli archives. -

My Life Story Malca Flasterstein

My Life Story Malca Flasterstein Josie Raborar, Storykeeper Acknowledgement As we near the consummation of the Ethnic Life Stories Project, there is a flood of memories going back to the concept of the endeavor. The awareness was there that the project would lead to golden treasures. But I never imagined the treasures would overflow the storehouse. With every Story Teller, every Story Keeper, every visionary, every contributor, every reader, the influence and impact of the project has multiplied in riches. The growth continues to spill onward. As its outreach progresses, "boundaries" will continue to move forward into the lives of countless witnesses. Very few of us are "Native Americans." People from around the world, who came seeking freedom and a new life for themselves and their families, have built up our country and communities. We are all individuals, the product of both our genetic makeup and our environment. We are indeed a nation of diversity. Many of us are far removed from our ancestors who left behind the familiar to learn a new language, new customs, new political and social relationships. We take our status as Americans for granted. We sometimes forget to welcome the newcomer. We bypass the opportunity to ask about their origins and their own journey of courage. But, wouldn't it be sad if we all spoke the same language, ate the same food, and there was no cultural diversity. This project has left me with a tremendous debt of gratitude for so many. The almost overwhelming task the Story Keeper has, and the many hours of work and frustration to bring forth a story to be printed. -

Registration for and Assignment to Post- Primary Schools

Registration for and Assignment to Post- Primary Schools This page includes: State schools State religious schools Arab schools In Tel Aviv-Yafo, students transition to post-primary education upon entering junior high in Grade 7. During November, Grade 6 students at municipal schools will receive a text message containing their assignment for the next school year. The assignment is determined according to the education region the primary school they study at belongs to. In the next school year (5782-2021-22), there will be 27 6-year schools and 10 3-4 year schools operating in the city. Students who wish to apply for another assignment or those who are required to conduct other registration processes (changing of stream, external studies, etc.) can do so in the ways and at the times set forth on this page. The post-primary school registration and assignment system > Registration leaflet for the 5782 (2021-22) school year - state religious education 5782 (2021-22) post-primary registration leaflet Arabic 5782 (2021-22) post-primary registration leaflet Unique transfers in post-primary education Important dates Important dates Date Description By the end of Receipt of the message of assignment at the post- November primary school in your education region on the website By the end of Tryout days for sports classes December January 3-14 Parents’ evenings at post-primary schools, by education region on the website By February 20 Submission of requests for transfer from the nine- year schools to the education region Important dates Date -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8.