My Life Story Malca Flasterstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

TEL AVIV-YAFO 341 Sister — Snowski

TEL AVIV-YAFO 341 Sister — Snowski Sister Dr Moshe 68 Ussishkin. 44 01 90 Skcwronek Jacob Slonim Yigal Advct 53 Reines. .23 57 34 Smilar Shelomo I Derech Haifa.22 57 52 Sitman Mordechai Pattern Wkshp 13 Habanim R'G 72 89 32 Slonim Yitzhak 26 Gordon . 22 16 13 Smilg Moses 65 Frishman 22 73 04 128 Giborei Yisrael 3 17 52 Skubatz Samuel (Bldg Contr) & Bronia Res 37 Balfour 61 25 62 Smilovici Albert Advct Siton Leon Rstnt Ankara 8 Arlosoroff Holon 84 87 05 Slonim Yitzhak Ins Agt 6 Ahuzat Bayit 5 31 69 13 Akiva Arye 5 93 70 Skubelski Szaja Cafe-Tnuva I Derech P-T 62 17 56 Smilovitch Sam 35a Hayarkon.. .5 95 88 Sitronenbaum Jakob David Grocery Res 21 Yehonathan R"G . .72 79 33 205 Dizengoff 22 08 55 SMILOVITZ MIRIAM LADIES' 26 Haroeh R"G 72 88 63 Skula Milka & Baruch Slonim Zvi FASHIONS 45 Ben Yehuda.23 56 91 Sitruk Sion 14 Carmeli Ramat Hen 3 61 60 10 Yehuda Halevi B"B 72 79 82 Smilowitz Sylvia Broker's 22 Jabotinsky Holon 84 62 49 Skulnik & Zwas Chldn Clthng Slonimski S 5 Achiezer 3 13 18 59 Hayarkon 5 88 05 Sitshin Zeev Grocery 53 Ben Yehuda 22 79 96 Slonimsky Israel Smiltiner I 28 Shivat Zion 82 40 67 34 Shalom Aleichem 22 57 54 Skulnik Aharon Embroidery 33 Reading Ramat Aviv 44 50 74 Smiltiner S Sitt Bros Ladies' Dresses 20 Tchernichovsky 23 26 02 Slor Mordechai Advct 2 Rotberg Givatayim 73 16 68 69 Allenby 62 30 55 Skulsky Shelomo 31 Sederot Rothschild 62 12 30 Smith Shulamith Shikun Ledugma 22 SArmcnim R"G 72 27 53 Sitt Mazal & Jacob 19 Allenby . -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

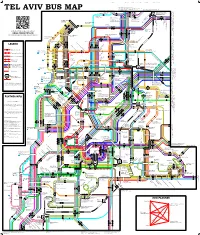

On July 1St the Public Transportation System in Tel Aviv Will Change Dramatically

Dear residents of Ramat Aviv and Tel Aviv University students, On July 1st the public transportation system in Tel Aviv will change dramatically. The official booklet explaining the transport reform may be nice and detailed, but it doesn't really explain how to get from TRANSPORT OUR WAY point A to point B. Israeli public transport This is what we're here for. consumer organization General information: 1. System-wide change in ticket prices: a single ticket (₪6.40) will allow unlimited transfers within 90 minutes in Tel Aviv and neighboring towns, on all bus companies (Dan, Egged, Kavim, Metropolin). 2. The changes that will take place July 1st , apply only to bus routes in Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan, Beni Brak, Bat Yam, Holon and Givatayim. Buses to Petah-Tikva, Rishon le-Tziyon, Rosh Ha’ayin, Hertzliyah and other cities, remain unchanged. Summary of changes in Ramat Aviv, Azorey Hen, Kiryat Chinuch, Afeka, Neve Avivim and to/from Tel Aviv University The #27, #29, #45, #74 and #86 bus lines will be cancelled. They will be replaced by the following buses, to Tel Aviv and Holon: o #171: Azorey Hen, Kakal Blvd., Haim Levanon, Einstein, Brodetzky, Arlozorov (Merkaz/Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, Ha-hagana Railway Station, and then continuing to Holon on a route similar to the #173. o #271: Kalachkin Terminal, Klauzner, George Wise, Arlozorov (Merkaz / Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, and then continuing to Holon .אon the same route as the #74 o #71: Kiryat Chinuch, Levi Eshkol Blvd., Arlozorov (Merkaz / Savidor) Railway Station, Azrieli Shopping Mall, and then continuing to Holon on a route similar to the #73. -

Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” As a Means to Instill Fundamentally Negative Messages Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center at the Center for Special Studies (C.S.S) Special Information Bulletin November 2003 Geography and Politics: Maps of “Palestine” as a means to instill fundamentally negative messages regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict The maps of “Palestine” distributed by the Palestinian Authority and other PA elements are an important and tangible method of instilling fundamentally negative messages relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These include ignoring the existence of the State of Israel, and denying the bond between the Jewish people and the Holyland; the obligation to fulfill the Palestinian “right of return”; the continuation of the “armed struggle” for the “liberation” of all of “Palestine”, and perpetuating hatred of the State of Israel. Hence, significant changes in the maps of “Palestine” would be an important indicator of a real willingness by the Palestinians to recognize the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish state and to arrive at a negotiated settlement based on the existence of two states, Israel and Palestine, as envisaged by President George W. Bush in the Road Map. The map features “Palestine” as distinctly Arab-Islamic, an integral part of the Arab world, and situated next to Syria, Egypt and Lebanon. Israel is not mentioned. (Source: “Natioal Education” 2 nd grade textbook, page 16, 2001-2002). Abstract The aim of this document is to sum up the findings regarding maps of “Palestine” (and the Middle East) circulated in the Palestinian areas by the PA and its institutions, and by other organizations (including research institutions, charities, political figures, and terrorist organizations such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad). -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Metropolitan Jerusalem - August 2006

Metropolitan Jerusalem - August 2006 Jalazun OFRA BET TALMON EL . RIMMONIM 60 Rd Bil'in Surda n llo Beitin Rammun A DOLEV Ramallah Deir Deir Ain DCO Dibwan Ibzi Al Chpt. Arik Ramallah Bireh G.ASSAF Beit Ur 80 Thta. Beituniya Burka 443 Beit Ur PSAGOT Fqa. MIGRON MA'ALE KOCHAV MIKHMAS BET YA'ACOV HORON Kufr Aqab Tira Rafat Mukhmas GIV'AT Kalandiya Beit Chpt. Liqya ZE'EV Beit Jaba GEVA Dukku BINYAMIN Jib Bir Ram Beit Nabala Inan Beit Ijza G.HAHADASHA B. N.YA'ACOV Qubeibe Hanina ALMON/ Bld. Beit Hizma ANATOT Biddu N.Samwil Hanina Qatanna Beit 45 HARADAR Beit P.ZE'EV Iksa Shuafat KFAR Surik ADUMIM RAMOT 1 R.SHLOMO Anata 1 FR. E 1 R.ESHKOL HILL Isawiya Zayim WEST East Jerusalem OLD Tur CITY I S R A E L Azarya MA'ALE Silwan ADUMIM Abu Thuri Dis Container Chpt. KEDAR Sawahra EAST Beit TALPIOT Safafa G. Sh.Sa'ad HAMATOS Sur GILO Walaja Bahir HAR HAR Battir GILO HOMA Ubaydiya Numan Mazmuriya Husan B.Jala Chpt. Wadi Al Kh.Juhzum 5 Km Fukin Bethlehem Khas Khadr B.Sahur BETAR ILLIT Um Shawawra NEVE Rukba Irtas Hindaza Nahhalin DANIEL GEVA'OT 60 Jaba ROSH TZURIM Za'atara Kht. EFRATA W.Rahhal BAT ELAZAR AYIN Zakarya Harmala ALLON W.an Nis SHVUT Jurat KFAR ELDAD Surif KFAR ash Shama TEKOA ETZION NOKDIM Tuku' Safa MIGDAL W e s t B a n k Beit OZ Beit Ummar Fajjar Map : © Jan de Jong Palestinian Village, Green Line Main Palestinian City or Road Link Neighborhood Jerusalem Israeli Settlement, Separation Israeli Checkpoint Existing / Barrier and/or Gate Under Construction Trajectory Israeli (Re) Constructed Israeli Civil or Military Israeli Municipal Settler Road, Facility and Area Limit East Jerusalem Projected or Under Construction E 1-Plan Outline Settlement Area Planned Settlement East of the Barrier 60 Road Number Construction . -

7 APRIL, 2008 Yabad 6 Qaffin 60 Hermesh Mutilla Baka Mevo (KING DAVID HOTEL) Shr

2 6 71 60 90 65 ROJECTION OF P Rummana Silat Jalama Anin Harthiya Fakkua 71 Hinanit ISRAELI MAP PRESENTED ON Al Yamun Reihan Shaked Barta'a ® Jenin 7 APRIL, 2008 Yabad 6 Qaffin 60 Hermesh Mutilla Baka Mevo (KING DAVID HOTEL) Shr. Dotan Qabatya Arraba Raba Bardala 2 Zeita Zababda Kafr 600 KM ~ 10.6 % OF WEST BANK Ra'i Mechola Attil Ajja Meithalun Shadmot Deir Mechola TOTAL AREA PROPOSED al Ghusun Akkaba Rotem Shuweika 2 Jab'a * 452 KM ~ 8 % DEPICTED HERE AS PRESENTED 57 Silat Tubas adh Dhahr Anabta Maskiyot 90 Avnei 80 Tulkarm Hefetz 57 Far'un Far'a Einav 60 557 Shavei Tammun Jubara Shufa Shomron Asira 57 Beit Shm. Hemdat Lid Ro'i Baron 557 Salit Industrial Elon Beqa'ot More Kedumim Frush 6 Kafr Bt.Dajan Falamya Qaddum Tzufim Nablus Jayyus 55 Tell Hamra Funduk Bracha 60 Awarta Qalqilya Immatin Beit Azzun Karnei Furik Argaman Shomron Mechora Yizhar Maale Itamar Zbeidat Shomron Nofim Alfei Imanuel Jiftlik Menashe Sha'arei Deir Jamma'in Beita Tikva Istiya Akraba 80 5 Oranit Etz K.Haris Kfar 505 Elkana EfraimBidya Revava Tapuah 57 Kiryat Masu'a Qabalan JORDAN 5 Netafim Ariel Barkan Rehelim Migdalim Gitit Maale Bruchin Eli Deir Alei Zahav 505 Efrayim 6 Ballut Yafit 90 Kufr Farkha Salfit 60 Pduel ad Dik Shilo 446 Petzael Ma'ale Duma Beit Arie Levona Bani Turmus Zeid Sinjil Ayya Fasayil Ofraim Rantis Abud Tomer Halamish Ateret Gilgal 60 Netiv Qibya Ha'gdud Nahliel 1 Bir Silwad Niran L E G E N D Na'ale Zeit Kharbatha Nili Ofra Kochav Ni'lin Dr.Kaddis Hashahar Yitav Beit El Awja Midya Modi'in Talmon Illit Bil'in 1967 Boundary (“Green Line”) Rimonim Hashmonaim Deir Dolev Dibwan 1 Ramallah Al Bira Na'ama 6 458 Mevo'ot Kfar Saffa Jericho Haoranim Beit Ur Tht. -

Registration for and Assignment to Post- Primary Schools

Registration for and Assignment to Post- Primary Schools This page includes: State schools State religious schools Arab schools In Tel Aviv-Yafo, students transition to post-primary education upon entering junior high in Grade 7. During November, Grade 6 students at municipal schools will receive a text message containing their assignment for the next school year. The assignment is determined according to the education region the primary school they study at belongs to. In the next school year (5782-2021-22), there will be 27 6-year schools and 10 3-4 year schools operating in the city. Students who wish to apply for another assignment or those who are required to conduct other registration processes (changing of stream, external studies, etc.) can do so in the ways and at the times set forth on this page. The post-primary school registration and assignment system > Registration leaflet for the 5782 (2021-22) school year - state religious education 5782 (2021-22) post-primary registration leaflet Arabic 5782 (2021-22) post-primary registration leaflet Unique transfers in post-primary education Important dates Important dates Date Description By the end of Receipt of the message of assignment at the post- November primary school in your education region on the website By the end of Tryout days for sports classes December January 3-14 Parents’ evenings at post-primary schools, by education region on the website By February 20 Submission of requests for transfer from the nine- year schools to the education region Important dates Date