Airbnb in the Matrix of Gentrification and Colonization by Viktori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

An Urban Miracle Geddes @ Tel Aviv the Single Success of Modern Planning Editor: Thom Rofe Designed by the Author

NAHOUM COHEN ARCHITECT & TOWN PLANNER AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV THE SINGLE SUCCESS OF MODERN PLANNING EDITOR: THOM ROFE DESIGNED BY THE AUTHOR WWW.NAHOUMCOHEN.WORDPRESS.COM ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE AUTHOR WRITTEN AND PUBLISHED BY THE KIND ASSISTANCE OT THE TEL AVIV MUNICIPALITY NOTE: THE COMPLETE BOOK WILL BE SENT IN PDF FORM ON DEMAND BY EMAIL TO - N. COHEN : [email protected] 1 NAHOUM COHEN architect & town planner AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE INTRODUCTION 11 PART TWO THE SETTING 34 PART THREE THE PLAN 67 3 PART FOUR THE PRESENT 143 PART FIVE THE FUTURE 195 ADDENDA GEDDES@TEL AVIV 4 In loving memory of my parents, Louisa and Nissim Cohen Designed by the Author Printed in Israel 5 INTRODUCTION & FOREWORD 6 Foreword The purpose of this book is twofold. First, it aims to make known to the general public the fact that Tel Aviv, a modern town one hundred years of age, is in its core one of the few successes of modern planning. Tel Aviv enjoys real urban activity, almost around the clock, and this activity contains all the range of human achievement: social, cultural, financial, etc. This intensity is promoted and enlivened by a relatively minor part of the city, the part planned by Sir Patrick Geddes, a Scotsman, anthropologist and man of vision. This urban core is the subject of the book, and it will be explored and presented here using aerial photos, maps, panoramic views, and what we hope will be layman-accessible explanations. -

Arab/Israeli Conflict Today Instructor: Dr

HIS 130A-01 - Arab/Israeli Conflict Today Instructor: Dr. Avi Marcovitz Fall 2016, Wednesday Email: [email protected] Time: 14:00 – 15:30 Phone: 050-300-7232 2 credits Course Description: This course provides an intensive, demanding and often emotional immersion into the historical, cultural and political aspects of the Middle East from a variety of experts. Throughout the semester, students will learn about the important sites in the area and possibly meet with individuals and groups that are active in Israel- Arab affairs. Students will benefit from a unique view of the conflict between Israel and the Arab world and gain insights and experiences that most students are not exposed to. These are intellectually challenging encounters designed to enable the students to become more knowledgeable and to learn to intelligently discuss the complex nature of what happens in Israel and the Palestinian territories. The course includes exposure to some controversial points of view, difficult sights and potentially confusing experiences. Our approach requires students to listen carefully and patiently digest the information, some of which includes differing perspectives on the same historical and contemporary events. The complicated and complex nature of the subject area requires active attention and participation in all activities and lectures, during the semester. Lectures will feature all sides of the political spectrum (Jews and Arabs and Palestinians and Israelis.) Classes are interactive experiences that review topics related to current events an in detail. Assigned reading and writing exercises as well as examinations will be required, as in any academic course. Throughout the course, students will view many examples of video footage from the Israeli, Palestinian and world media, participate in class debates over contemporary issues, and learn to respond to some of the most common allegations and threats facing Israel, such as the Apartheid accusation, the origin and predicament of the refugees and the emerging Iranian threat. -

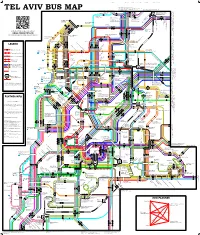

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VENEZIA L'orgoglio ESIBITO Dipartimento Di Studi Umanistici Corso Di Laurea in Antropologia Cultura

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VENEZIA L’ORGOGLIO ESIBITO Dipartimento di Studi umanistici Corso di Laurea in Antropologia culturale, Etnografia ed Etnolinguistica Tesi di laurea magistrale in Antropologia visiva Relatore: Ch.ma Professoressa BONIFACIO VALENTINA Correlatori: Ch.ma Professoressa TAMISARI FRANCA Ch.mo Professore BONESSO GIANFRANCO DIEGO BATTAGLIA Matricola n. 840084 III SESSIONE ANNO ACCADEMICO 2018 -2019 1 2 DEGLI ARGOMENTI DEGLI ARGOMENTI .................................................................................................... pag. 3 A MO’ DI INTRODUZIONE ......................................................................................... pag. 5 Questioni metodologiche .................................................................................................. pag. 6 Posizionamento ................................................................................................................. pag. 14 Bridge.................................................................................................................................. pag. 17 Tavole ................................................................................................................................. pag. 24 UNA DOVUTA NOTA INIZIALE ................................................................................. pag. 35 Tavole ................................................................................................................................ pag. 40 TELAVIVING .................................................................................................................. -

Mythos Israel Israel Dr

60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Israel = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung Dr. Viktoria Waltz, München 9.12.09 60 Jahre Planung im neuen Jüdischen Staat Mythos Israel Israel Dr. Viktoria Waltz 9.12.09 = 60 Jahre Enteignung und Ausgrenzung der autochthonen palästinensischen Bevölkerung 0. Ausgangssituation und Probleme der Neugründung 15. Mai 1948 zionistische Kolonien, palästinensische Orte Bevölkerungsverteilung Bodeneigentum Machtverhältnisse 1. Verfassung und Bürgerrechte 2. Einwanderung und Ansiedlung von Immigranten 3. Raumplanung Landenteignung Organe und Planungen Nationalplan 1950 Kibbuzim und Moshavim New Towns (Beispiele Kiryat Gad, Ashkelon, Ramleh, Jaffa) Wasser, Parks Planungssystem Kartenübersicht UN-Teilung 1947 Topographie und Lage ‚Tourismus„-Karte, 56,7% ‚‚jewish„ nach 1948 (70%„ jewish„) - mit ‚Golan„ (100%?) Letzte Phase vor der Staatsgründung 1948 Kolonien 1945 Palästinensische Dörfer und Städte Die Utopie von 1945 einem ‚leeren Land‘ 1948 Lage des bis 1946 durch den JNF gekauften Landes Quellen: Grannott 1956, Richter 1969, Waltz/Zschiesche 1986 Situation 14. May 1948 im Staatsgebiet Israel • Jüdische Seite Palästinensische Seite ca. 700.000 EW, davon ca. 156.000 EW, und ca. 330.812 ca. 50% Geflohene 750.000 Vertriebene (Nakba) aus Europa (Faschismus) Konzentriert mit 90% im Konzentriert mit 80% in den Inneren des Landes: Küstenstädten zwischen: - Negev (Beduinen) - Tel Aviv und - ‚Dreieck„ um Um el Fahem - Haifa - Galiläa mit Nazareth Als jüdische Mehrheit -

Places to Visit in Tel Aviv

Places to visit in Tel Aviv Tel Aviv – North The Yitzhak Rabin Center The Yitzhak Rabin Center is the national institute established by the Knesset in 1997 that advances the legacy of the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, a path-breaking, visionary leader whose life was cut short in a devastating assassination. The Center presents Yitzhak Rabin’s remarkable life and tragic death, pivotal elements of the history of Israel, whose impact must not be ignored or forgotten lest risk the recurrence of such shattering events. The Center’s mission is to ensure that the vital lessons from this story are actively remembered and used to shape an Israeli society and leadership dedicated to open dialogue, democratic value, Zionism and social cohesion. The Center promotes activities and programs that inspire cultured, engaged and civil exchanges among the different sectors that make up the complex mosaic of Israeli society. The Israeli Museum at the Yitzhak Rabin Center is the first and only museum in Israel to explore the development of the State of Israel as a young democracy. Built in a downward spiral, the Museum presents two parallel stories: the history of the State and Israeli society, and the biography of Yitzhak Rabin. The Museum’s content was determined by an academic team headed by Israeli historian, Professor Anita Shapira. We recommend allocating from an hour and thirty minutes to two hours for a visit. The Museum experience utilizes audio devices that allow visitors to tour the Museum at their own pace. They are available in Hebrew, English and Arabic. -

Israel: a Mosaic of Cultures Touring Israel to Encounter Its People, Art, Food, Nature, History, Technology and More! May 30- June 11, 2018 (As of 8/28/17)

Israel: A Mosaic of Cultures Touring Israel to encounter its People, Art, Food, Nature, History, Technology and more! May 30- June 11, 2018 (As of 8/28/17) Day 1: Wednesday May 30, 2018: DEPARTURE Depart the United States via United Airlines on our overnight flight to Israel. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 2: Thursday, May 31, 2018: WELCOME TO ISRAEL! We arrive at Ben Gurion Airport in the early afternoon, and are assisted by an Ayelet Tours representative. Welcome home! Our tour begins with a visit to Independence Hall, site of the signing of Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948, including the special exhibits for Israel’s 70th. We conclude our visit with a moving rendition of Hatikva. We travel now from the past to the present. We visit the Taglit Innovation Center for a glimpse into Israel’s hi-tech advances in the fields of science, medicine, security and space. We visit the interactive exhibit and continue with a meeting with one of Israel’s leading entrepreneurs. We check in to our hotel and have time to refresh. This evening, we enjoy a welcome dinner and tour orientation with our expert guide at a local gourmet restaurant Overnight at the Crowne Plaza Hotel, Tel Aviv --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 3: Friday, June 1, 2018: ISRAEL PAST TO PRESENT Breakfast at our hotel. Visit the Israel Sports Center for the Disabled in Ramat Gan for a special program with Paralympic medal winner, Pascale Bercovitch. Experience the multi-ethnic weave of Tel Aviv through tastings at the bustling Levinsky Market, with tastes and aromas from all over the Balkans and Greek Isles. -

Knights for Israel Honored at Camera Gala 2018 a Must-See Film

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 40 JUNE 8, 2018 25 SIVAN, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ JNF’s Plant Your Way website NEW YORK—Jewish Na- it can be applied to any Jewish tional Fund revealed its new National Fund trip and the Plant Your Way website that Alexander Muss High School easily allows individuals to in Israel (AMHSI-JNF) is a raise money for a future trip huge bonus because donors to Israel while helping build can take advantage of the 100 the land of Israel. percent tax deductible status First introduced in 2000, of the contributions.” Plant Your Way has allowed Some of the benefits in- many hundreds of young clude: people a personal fundraising • Donations are 100 percent platform to raise money for a tax deductible; trip to Israel while giving back • It’s a great way to teach at the same time. Over the children and young adults the last 18 years, more than $1.3 basics of fundraising, while million has been generated for they build a connection to Jewish National Fund proj- Israel and plan a personal trip Knights for Israel members (l-r): Emily Aspinwall, Sam Busey, Jake Suster, Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz and Benji ects, typically by high school to Israel; Osterman, accepted the David Bar-Ilan Award for Outstanding Campus Activism. students. The new platform • Funds raised can be ap- allows parents/grandparents plied to any Israel trip (up to along with family, friends, age 30); coworkers and classmates • Participant can designate Knights for Israel honored to open Plant Your Way ac- to any of Jewish National counts for individuals from Fund’s seven program areas, birth up to the age of 30, and including forestry and green at Camera Gala 2018 for schools to raise money for innovation, water solutions, trips as well. -

THE HEBRON FUND CALENDAR September 2020-December 2021 תשפ"א/5781 We Hope You’Ve Enjoyed the Hebron Fund Artists Calendar and Have a Happy and Healthy New Year

THE HEBRON FUND CALENDAR September 2020-December 2021 תשפ"א/5781 We hope you’ve enjoyed the Hebron Fund Artists Calendar and have a happy and healthy New Year. To become a supporter, please donate at http://donate.hebronfund.org/calendar-campaign or contact (718) 677-6886 and we will mail you your own copy! Teddy Pollak Rabbi Daniel Rosenstein Rabbi Hillel Horowitz Rabbi Simcha Hochbaum President Executive Director Mayor of Hebron Director of Tourism The Hebron Fund The Hebron Fund The Hebron Fund Ester Arieh Tzippy Rapp Sali Cherniak Sarah Edri Executive Secretary Project Manager Projects Coordinator Tour Coordinator The Hebron Fund The Hebron Fund The Hebron Fund The Hebron Fund Uri Karzen Yishai Fleisher Noam Arnon Yoni Bliechbard Director General International Spokesman Spokesman Chief Security Officer Hebron Jewish Community Hebron Jewish Community Hebron Jewish Community Hebron Jewish Community The Hebron Fund Objectives • Support Hebron Families • Beautify & Maintain Holy Sites • Sponsor Public Events & Increase Visitors • Israel Advocacy, Education & Diplomacy • Educational & Recreational Projects • Inspiring & Caring for IDF Soldiers To learn more visit us at hebronfund.org Times republished with permission from MyZmanim.com. All New York times listed are for the 11230 zip code. Shabbat end times are based on the opinion of Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Tukaccinsky, which is usually 50 min past sundown. ישתבח שמו לעד – ברוך נחשון | May His Name Be Blessed Forever – Baruch Nachshon אלול תש"פ – תשרי תשפ"א SEPTEMBER 2020 ELUL 5780 – TISHREI 5781 שבת SATURDAY שישי FRIDAY חמישי THURSDAY רביעי WEDNESDAY שלישי TUESDAY שני MONDAY ראשון SUNDAY ט״ז Elul 16 5 ט״ו Elul 15 4 י״ד Elul 14 3 י״ג Elul 13 2 י״ב Elul 12 1 כי תבוא שנה טובה ומתוקה Best wishes for a CANDLE LIGHTING SHABBAT ENDS Happy & Healthy New Year! New York 7:04pm New York 8:02pm Miami 7:18pm Miami 8:10pm Enjoy The Hebron Fund 16-Month Chicago 6:57pm Chicago 7:59pm Los Angeles 6:55pm Los Angeles 7:51pm Artists Calendar. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

Israel ISRAEL

Israel I.H.T. Industries: food processing, diamond cutting and polishing, textiles and ISRAEL apparel, chemicals, metal products, military equipment, transport equipment, electrical equipment, potash mining, high-technology electronics, tourism Currency: 1 new Israeli shekel (NIS) = 100 new agorot Railways: total: 610 km standard gauge: 610 km 1.435-m gauge (1996) Highways: total: 15,965 km paved: 15,965 km (including 56 km of expressways) unpaved: 0 km (1998 est.) Ports and Harbors: Ashdod, Ashqelon, Elat (Eilat), Hadera, Haifa, Tel Aviv- Yafo Airports: 58 (1999 est.) Airports - with paved runways: total: 33 over 3,047 m: 2 2,438 to 3,047 m: 7 1,524 to 2,437 m: 7 914 to 1,523 m: 10 under 914 m: 7 (1999 est.) Airports - with unpaved runways: total: 25 2,438 to 3,047 m: 1 1,524 to 2,437 m: 2 914 to 1,523 m: 2 under 914 m: 20 (1999 est.) Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) Visa: required by all on arrival, subject to frequent changes. goods permitted: 250 cigarettes or 250g of tobacco products, 1 litre Duty Free: of spirits and 2 litres of wine, 250ml of eau de cologne or perfume, gifts up to the value of US$125. Health: no specific health precautions. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS BEERSHEBA Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++972 THE BEERSHEBA DESERT INN LTD Ministry of Tourism: PO Box 1018 King George Street 24 Jerusalem Tel: (2) 675 Tuviyahu Av 4811 Fax: (2) 625 7955 Website: www.infotour.co.ul P.O.Box 247 TEL: +972 7 642 4922-9 Capital: Jerusalem Time: GMT + 2 Beersheba 84 102 FAX:+972 7 6412 772 Background: Following World War II, the British withdrew from their mandate of ISRAEL www.desertinn-hotel.com Palestine, and the UN partitioned the area into Arab and Jewish states, an E-mail: [email protected] arrangement rejected by the Arabs.