The Last Mosque in Tel Aviv, and Other Stories of Disjuncture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

SEX (Education)

A Guide to Eective Programming for Muslim Youth LET’S TALK ABOUT SEX (education) A Resource Developed by the HEART Peers Program i A Guide to Sexual Health Education for Muslim Youth AT THE heart of the CENTRAL TO ALL MATTER WORKSHOPS WAS THE HEART Women & Girls seeks to promote the reproductive FOLLOWING QUESTION: health and mental well-being of faith-based communities through culturally-sensitive health education. How can we convey information about sexual Acknowledgments About the Project and reproductive health This toolkit is the culmination of three years of research The inaugural peer health education program, HEART and fieldwork led by HEART Women & Girls, an Peers, brought together eight dynamic college-aged to American Muslim organization committed to giving Muslim women and Muslim women from Loyola University, the University girls a safe platform to discuss sensitive topics such as of Chicago, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison women and girls in a body image, reproductive health, and self-esteem. The for a twelve-session training on sexual and reproductive final toolkit was prepared by HEART’s Executive Director health, with a special focus on sexual violence. Our eight manner that is mindful Nadiah Mohajir, with significant contributions from peer educator trainees comprised a diverse group with of religious and cultural Ayesha Akhtar, HEART co-founder & former Policy and respect to ethnicity, religious upbringing and practice, Research Director, and eight dynamic Muslim college- and professional training. Yet they all came together values and attitudes aged women trained as sexual health peer educators. for one purpose: to learn how to serve as resources for We extend special thanks to each of our eight educators, their Muslim peers regarding sexual and reproductive and also advocates the Yasmeen Shaban, Sarah Hasan, Aayah Fatayerji, Hadia health. -

Houses Built on Sand: Violence, Sectarianism and Revolution in the Middle East

125 5 Building Beirut, transforming Jerusalem and breaking Basra Empires collapse. Gang leaders are strutting about like statesmen. The peoples Can no longer be seen under all those armaments. So the future lies in darkness and the forces of right Are weak. All this was plain to you. Walter Benjamin, On the Suicide of the Refugee Cities of Salt, a novel by Abdelrahman Munif set in an unnamed Gulf kingdom tells the story of the transformation of Wadi Al Uyan by Americans after the discovery of oil.1 The wadi, initially described as a ‘salvation from death’ amid the treacherous desert heat, played an important role in the lives of the Bedouin community of the unnamed kingdom – although the reader quickly draws parallels with Saudi Arabia – and its ensuing destruction has a devastating impact upon the people who lived there. The novel explores tensions between tradition and modernity that became increasingly pertinent after the discovery of oil, outlining the transformation of local society amid the socio-eco nomic development of the state. The narrative reveals how these developments ride roughshod over tribal norms that had long regulated life, transforming the regulation and ordering of space, grounding the exception within a territorially bounded area. It was later banned by a number of Gulf states. Although fictional, the novel offers a fascinating account of the evolution of life across the Gulf. World Bank data suggests that 65% of the Middle East’s population live in cities, although in Kuwait this is 98%, in Qatar it is 99%, but in Yemen it is only 35%.2 Legislation designed to regulate life finds most traction within urban areas, where jobs and welfare projects offer a degree of protection. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

Israeli Reactions in a Soviet Moment: Reflections on the 1970 Leningrad Affair

No. 58 l September 2020 KENNAN CABLE Mark Dymshits, Sylva Zalmanson, Edward Kuznetsov & 250,000 of their supporters in New York Ciry, 1979. (Photo:Courtesy of Ilya Levkov; CC-BY-SA) Israeli Reactions in a Soviet Moment: Reflections on the 1970 Leningrad Affair By Jonathan Dekel-Chen The Kennan Institute convened a virtual meeting and public demonstrators pushed the Kremlin to retry in June 2020 marking the 50th anniversary of the the conspirators, commute death sentences for their attempted hijacking of a Soviet commercial flight from leaders, and reduce the prison terms for the rest. Leningrad.1 The 16 Jewish hijackers hoped to draw international attention to their struggle for emigration to A showing of the 2016 documentary filmOperation Israel, although many of them did not believe that they Wedding (the code name for the hijacking) produced by would arrive at their destination. Some were veterans Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, daughter of two conspirators, of the Zionist movement who had already endured preceded the Kennan panel and served as a backdrop punishment for so-called “nationalist, anti-Soviet for its conversations. The film describes the events from crimes,” whereas others were newcomers to activism.2 the vantage point of her parents. As it shows, the plight Their arrest on the Leningrad airport tarmac in June of the hijackers—in particular Edward Kuznetsov and 1970, followed by a show trial later that year, brought Sylva Zalmanson—became a rallying point for Jewish the hijackers the international attention they sought. and human rights activists in the West. Both eventually Predictably, the trial resulted in harsh prison terms. -

Tafsir Ibn Kathir Alama Imad Ud Din Ibn Kathir

Tafsir Ibn Kathir Alama Imad ud Din Ibn Kathir Tafsir ibn Kathir , is a classic Sunni Islam Tafsir (commentary of the Qur'an) by Imad ud Din Ibn Kathir. It is considered to be a summary of the earlier Tafsir al-Tabari. It is popular because it uses Hadith to explain each verse and chapter of the Qur'an… Al A'la The Virtues of Surat Al-A`la This Surah was revealed in Makkah before the migration to Al-Madinah. The proof of this is what Al-Bukhari recorded from Al-Bara' bin `Azib, that he said, "The first people to come to us (in Al-Madinah) from the Companions of the Prophet were Mus`ab bin `Umayr and Ibn Umm Maktum, who taught us the Qur'an; then `Ammar, Bilal and Sa`d came. Then `Umar bin Al-Khattab came with a group of twenty people, after which the Prophet came. I have not seen the people of Al-Madinah happier with anything more than their happiness with his coming (to Al-Madinah). This was reached to such an extent that I saw the children and little ones saying, `This is the Messenger of Allah who has come.' Thus, he came, but he did not come until after I had already recited (i.e., learned how to recite). 3 , Glorify the Name of your Lord, the Most High. (87:1) as well as other Surahs similar to it.'' It has been confirmed in the Two Sahihs that the Messenger of Allah said to Mu`adh, Why didn't you recite, 3 , !" - Glorify the Name of your Lord, the Most High, (Surah 87); - By the sun and its brightness, (Surah 91); - By the night when it envelopes. -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

An Urban Miracle Geddes @ Tel Aviv the Single Success of Modern Planning Editor: Thom Rofe Designed by the Author

NAHOUM COHEN ARCHITECT & TOWN PLANNER AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV THE SINGLE SUCCESS OF MODERN PLANNING EDITOR: THOM ROFE DESIGNED BY THE AUTHOR WWW.NAHOUMCOHEN.WORDPRESS.COM ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE AUTHOR WRITTEN AND PUBLISHED BY THE KIND ASSISTANCE OT THE TEL AVIV MUNICIPALITY NOTE: THE COMPLETE BOOK WILL BE SENT IN PDF FORM ON DEMAND BY EMAIL TO - N. COHEN : [email protected] 1 NAHOUM COHEN architect & town planner AN URBAN MIRACLE GEDDES @ TEL AVIV 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE INTRODUCTION 11 PART TWO THE SETTING 34 PART THREE THE PLAN 67 3 PART FOUR THE PRESENT 143 PART FIVE THE FUTURE 195 ADDENDA GEDDES@TEL AVIV 4 In loving memory of my parents, Louisa and Nissim Cohen Designed by the Author Printed in Israel 5 INTRODUCTION & FOREWORD 6 Foreword The purpose of this book is twofold. First, it aims to make known to the general public the fact that Tel Aviv, a modern town one hundred years of age, is in its core one of the few successes of modern planning. Tel Aviv enjoys real urban activity, almost around the clock, and this activity contains all the range of human achievement: social, cultural, financial, etc. This intensity is promoted and enlivened by a relatively minor part of the city, the part planned by Sir Patrick Geddes, a Scotsman, anthropologist and man of vision. This urban core is the subject of the book, and it will be explored and presented here using aerial photos, maps, panoramic views, and what we hope will be layman-accessible explanations. -

The Colonizing Self Or, Home and Homelessness in Israel / Palestine

The Colonizing Self Or, HOme and HOmelessness in israel / Palestine Hagar Kotef The Colonizing Self A Theory in Forms Book Series Editors Nancy Rose Hunt and Achille Mbembe Duke University Press / Durham and London / 2020 The Colonizing Self or, home and homelessness in israel/palestine Hagar Kotef © ���� duke university press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Richardson and typeset in Portrait by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Kotef, Hagar, [date] author. Title: The colonizing self : or, home and homelessness in Israel/Palestine / Hagar Kotef. Other titles: Theory in forms. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Series: Theory in forms | Includes biblio- graphical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020017127 (print) | lccn 2020017128 (ebook) isbn 9781478010289 (hardcover) isbn 9781478011330 (paperback) isbn 9781478012863 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Land settlement—West Bank. | Land settlement—Social aspects—West Bank. | Israelis—Colonization—West Bank. | Israelis—Homes and haunts—Social aspects—West Bank. | Israelis—West Bank—Social conditions. Classification: lcc ds110.w47 k684 2020 (print) | lcc ds110.w47 (ebook) ddc 333.3/156942089924—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017127 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017128 Cover art: © Marjan Teeuwen, courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery, NY. The cover image by the Dutch artist Marjan Teeuwen, from a series titled Destroyed House, is of a destroyed house in Gaza, which Teeuwen reassembled and photographed. This form of reclaiming debris and rubble is in conversation with many themes this book foregrounds—from the effort to render destruction visible as a critique of violence to the appropriation of someone else’s home and its destruction as part of one’s identity, national revival, or (as in the case of this image) a professional art exhibition. -

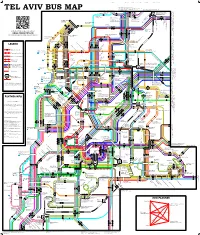

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Gandhi's View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious

religions Article Gandhi’s View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious Theology Ephraim Meir 1,2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 2 Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa Abstract: This article describes Gandhi’s view on Judaism and Zionism and places it in the framework of an interreligious theology. In such a theology, the notion of “trans-difference” appreciates the differences between cultures and religions with the aim of building bridges between them. It is argued that Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was limited, mainly because he looked at Judaism through Christian lenses. He reduced Judaism to a religion without considering its peoplehood dimension. This reduction, together with his political endeavors in favor of the Hindu–Muslim unity and with his advice of satyagraha to the Jews in the 1930s determined his view on Zionism. Notwithstanding Gandhi’s problematic views on Judaism and Zionism, his satyagraha opens a wide-open window to possibilities and challenges in the Near East. In the spirit of an interreligious theology, bridges are built between Gandhi’s satyagraha and Jewish transformational dialogical thinking. Keywords: Gandhi; interreligious theology; Judaism; Zionism; satyagraha satyagraha This article situates Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s in the perspective of a Jewish dialogical philosophy and theology. I focus upon the question to what extent Citation: Meir, Ephraim. 2021. Gandhi’s religious outlook and satyagraha, initiated during his period in South Africa, con- Gandhi’s View on Judaism and tribute to intercultural and interreligious understanding and communication. -

Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bet HaMikdash ; "The Holy House"), refers to Part of a series of articles on ,שדקמה תיב :The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple (Hebrew a series of structures located on the Temple Mount (Har HaBayit) in the old city of Jerusalem. Historically, two Jews and Judaism navigation temples were built at this location, and a future Temple features in Jewish eschatology. According to classical Main page Jewish belief, the Temple (or the Temple Mount) acts as the figurative "footstool" of God's presence (Heb. Contents "shechina") in the physical world. Featured content Current events The First Temple was built by King Solomon in seven years during the 10th century BCE, culminating in 960 [1] [2] Who is a Jew? ∙ Etymology ∙ Culture Random article BCE. It was the center of ancient Judaism. The Temple replaced the Tabernacle of Moses and the Tabernacles at Shiloh, Nov, and Givon as the central focus of Jewish faith. This First Temple was destroyed by Religion search the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Construction of a new temple was begun in 537 BCE; after a hiatus, work resumed Texts 520 BCE, with completion occurring in 516 BCE and dedication in 515. As described in the Book of Ezra, Ethnicities Go Search rebuilding of the Temple was authorized by Cyrus the Great and ratified by Darius the Great. Five centuries later, Population this Second Temple was renovated by Herod the Great in about 20 BCE.