Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Did Solomon Build the Temple? by Dr

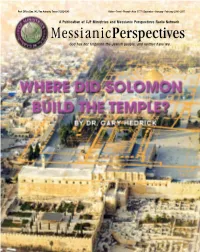

Post Office Box 345, San Antonio, Texas 78292-0345 Kislev –Tevet– Shevat–Adar 5777 / December– January– February 2016–2017 A Publication of CJF Ministries and Messianic Perspectives Radio Network MessianicPerspectives ® God has not forgotten the Jewish people, and neither have we. e are living in tumultuous times. Many things that Historical Background Wwe’ve always taken for granted are being called into question. The people of Israel had three central places of worship in ancient times: the Tabernacle, the First Temple, and the One hotly-disputed question these days is, “Were the an- Second Temple. Around 538 BC, the Jewish captives were cient Temples really on the Temple Mount?” You’d think released by King Cyrus of Persia to return from exile to the fact that Mount Moriah (and the manmade plat- their Land. Zerubbabel and Joshua the priest led the ef- form around it) has been known for many centuries as fort to rebuild the Second Temple, and work commenced “the Temple Mount”1 would provide an important clue, around 536 BC on the site of the First Temple, which the wouldn’t you? Babylonians had destroyed. The new Temple was simpler and more modest than its impressive predecessor had It’s a bit like the facetious query about who’s buried in been.2 Centuries later, when Yeshua sat contemplatively Grant’s tomb. Who else would be in that tomb but Mr. on the Mount of Olives with His disciples (Matt. 24), they Grant and what else would have been on the Temple looked down on the Temple Mount as King Herod’s work- Mount but the Temple? ers were busily at work remodeling and expanding the But not everyone agrees. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

Houses Built on Sand: Violence, Sectarianism and Revolution in the Middle East

125 5 Building Beirut, transforming Jerusalem and breaking Basra Empires collapse. Gang leaders are strutting about like statesmen. The peoples Can no longer be seen under all those armaments. So the future lies in darkness and the forces of right Are weak. All this was plain to you. Walter Benjamin, On the Suicide of the Refugee Cities of Salt, a novel by Abdelrahman Munif set in an unnamed Gulf kingdom tells the story of the transformation of Wadi Al Uyan by Americans after the discovery of oil.1 The wadi, initially described as a ‘salvation from death’ amid the treacherous desert heat, played an important role in the lives of the Bedouin community of the unnamed kingdom – although the reader quickly draws parallels with Saudi Arabia – and its ensuing destruction has a devastating impact upon the people who lived there. The novel explores tensions between tradition and modernity that became increasingly pertinent after the discovery of oil, outlining the transformation of local society amid the socio-eco nomic development of the state. The narrative reveals how these developments ride roughshod over tribal norms that had long regulated life, transforming the regulation and ordering of space, grounding the exception within a territorially bounded area. It was later banned by a number of Gulf states. Although fictional, the novel offers a fascinating account of the evolution of life across the Gulf. World Bank data suggests that 65% of the Middle East’s population live in cities, although in Kuwait this is 98%, in Qatar it is 99%, but in Yemen it is only 35%.2 Legislation designed to regulate life finds most traction within urban areas, where jobs and welfare projects offer a degree of protection. -

Penelitian Individual

3 ii COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH (THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND-STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY WALISONGO) GENDER AND IDENTITY POLITICS (DYNAMICS OF MOSLEM WOMEN IN AUSTRALIA) Researchers: Misbah Zulfa Elizabeth Lift Anis Ma’shumah Nadiatus Salama Academic Advisor: Dr. Morgan Brigg Dr. Lee Wilson Funded by DIPA UIN Walisongo 2015 iii iv PREFACE This research, entitled Gender and Identity Politics (Dynamics of Moslem Women in Australia) is implemented as the result of cooperation between State Islamic University Walisongo and The University of Queensland (UQ) Brisbane Australia for the second year. With the completion of this research, researchers would like to say thank to several people who have helped in the processes as well as in the completion of the research . They are 1 Rector of State Islamic University Walisongo 2. Chairman of Institute for Research and Community Service (LP2M) State Islamic University Walisongo 3. Chancellor of The UQ 4. Academic advisor from The UQ side : Dr. Morgan Brigg and Dr. Lee Wilson 5. All those who have helped the implementation of this study Finally , we must state that these report has not been perfect . We are sure there are many limitedness . Therefore, we are happy to accept criticism , advice and go for a more refined later . Semarang, December 2015 Researchers v vi TABLE OF CONTENT PREFACE — v TABLE OF CONTENT — vi Chapter I. Introduction A. Background — 1 B. Research Question — 9 C. Literature Review — 9 D. Theoretical Framework — 14 E. Methods — 25 Chapter II. Identity Politics and Minority-Majority Relation among Women A. Definition of Identity Politics — 29 B. Definition of Majority-Minority — 36 C. -

The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 7: The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The Ministry for Islamic Affairs, Endowments, Da’wah, and Guidance, commonly abbreviated to the Ministry of Islamic Affairs (MOIA), supervises and regulates religious activity in Saudi Arabia. Whereas the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) directly enforces religious law, as seen in Mapping the Saudi State, Chapter 1,1 the MOIA is responsible for the administration of broader religious services. According to the MOIA, its primary duties include overseeing the coordination of Islamic societies and organizations, the appointment of clergy, and the maintenance and construction of mosques.2 Yet, despite its official mission to “preserve Islamic values” and protect mosques “in a manner that fits their sacred status,”3 the MOIA is complicit in a longstanding government campaign against the peninsula’s traditional heritage – Islamic or otherwise. Since 1925, the Al Saud family has overseen the destruction of tombs, mosques, and historical artifacts in Jeddah, Medina, Mecca, al-Khobar, Awamiyah, and Jabal al-Uhud. According to the Islamic Heritage Research Foundation, between just 1985 and 2014 – through the MOIA’s founding in 1993 –the government demolished 98% of the religious and historical sites located in Saudi Arabia.4 The MOIA’s seemingly contradictory role in the destruction of Islamic holy places, commentators suggest, is actually the byproduct of an equally incongruous alliance between the forces of Wahhabism and commercialism.5 Compelled to acknowledge larger demographic and economic trends in Saudi Arabia – rapid population growth, increased urbanization, and declining oil revenues chief among them6 – the government has increasingly worked to satisfy both the Wahhabi religious establishment and the kingdom’s financial elite. -

Lincoln Square Synagogue for As Sexuality, the Role Of

IflN mm Lincoln Square Synagogue Volume 27, No. 3 WINTER ISSUE Shevat 5752 - January, 1992 FROM THE RABBI'S DESK.- It has been two years since I last saw leaves summon their last colorful challenge to their impending fall. Although there are many things to wonder at in this city, most ofthem are works ofhuman beings. Only tourists wonder at the human works, and being a New Yorker, I cannot act as a tourist. It was good to have some thing from G-d to wonder at, even though it was only leaves. Wondering is an inspiring sensation. A sense of wonder insures that our rela¬ tionship with G-d is not static. It keeps us in an active relationship, and protects us from davening or fulfilling any other mitzvah merely by rote. A lack of excitement, of curiosity, of surprise, of wonder severs our attachment to what we do. Worse: it arouses G-d's disappointment I wonder most at our propensity to cease wondering. None of us would consciously decide to deprive our prayers and actions of meaning. Yet, most of us are not much bothered by our lack of attachment to our tefilot and mitzvot. We are too comfortable, too certain that we are living properly. That is why I am happy that we hosted the Wednesday Night Lecture with Rabbi Riskin and Dr. Ruth. The lecture and the controversy surrounding it certainly woke us up. We should not need or even use controversy to wake ourselves up. However, those of us who were joined in argument over the lecture were forced to confront some of the serious divisions in the Orthodox community, and many of its other problems. -

Early Islamic Architecture in Iran

EARLY ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE IN IRAN (637-1059) ALIREZA ANISI Ph.D. THESIS THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2007 To My wife, and in memory of my parents Contents Preface...........................................................................................................iv List of Abbreviations.................................................................................vii List of Plates ................................................................................................ix List of Figures .............................................................................................xix Introduction .................................................................................................1 I Historical and Cultural Overview ..............................................5 II Legacy of Sasanian Architecture ...............................................49 III Major Feature of Architecture and Construction ................72 IV Decoration and Inscriptions .....................................................114 Conclusion .................................................................................................137 Catalogue of Monuments ......................................................................143 Bibliography .............................................................................................353 iii PREFACE It is a pleasure to mention the help that I have received in writing this thesis. Undoubtedly, it was my great fortune that I benefited from the supervision of Robert Hillenbrand, whose comments, -

Homeland, Identity and Wellbeing Amongst the Beni-Amer in Eritrea-Sudan and Diasporas

IM/MOBILITY: HOMELAND, IDENTITY AND WELLBEING AMONGST THE BENI-AMER IN ERITREA-SUDAN AND DIASPORAS Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester Saeid Hmmed BSc MSc (OU) Department of Geography University of Leicester September 2017 i Abstract This thesis focuses on how mobility, identity, conceptions of homeland and wellbeing have been transformed across time and space amongst the Beni-Amer. Beni-Amer pastoralist societies inhabit western Eritrea and eastern Sudan; their livelihoods are intimately connected to livestock. Their cultural identities, norms and values, and their indigenous knowledge, have revolved around pastoralism. Since the 1950s the Beni-Amer have undergone rapid and profound socio-political and geographic change. In the 1950s the tribe left most of their ancestral homeland and migrated to Sudan; many now live in diasporas in Western and Middle Eastern countries. Their mobility, and conceptions of homeland, identity and wellbeing are complex, mutually constitutive and cannot be easily untangled. The presence or absence, alteration or limitation of one of these concepts affects the others. Qualitatively designed and thematically analysed, this study focuses on the multiple temporalities and spatialities of Beni-Amer societies. The study subjected pastoral mobility to scrutiny beyond its contemporary theoretical and conceptual framework. It argues that pastoral mobility is currently understood primarily via its role as a survival system; as a strategy to exploit transient concentration of pasture and water across rangelands. The study stresses that such perspectives have contributed to the conceptualization of pastoral mobility as merely physical movement, a binary contrast to settlement; pastoral societies are therefore seen as either sedentary or mobile. -

The Misconception Series

THE MISCONCEPTION SERIES • LECTURE ONE – INTRODUCTION TO MISCONCEPTION SERIES o Why and how do misconceptions arise? o What are the effects of misconceptions? o Brief examples of current misconceptions o Brief overview of lecture series • LECTURE TWO – IS GOD INVOLVED IN THE WORLD? o Overview of a few misconceptions about God’s involvement in the world o What is the extent to which God is involved in the world? o Knowledge vs Judgement o Free will o What about rabbis who say natural disasters and diseases are judgements from God? • LECTURE THREE – COMMANDMENTS o Overview of a few misconceptions about keeping commandments/mitzvoth o Definition of a commandment/mitzvah o Why are we commanded to do mitzvoth if they are merely for our own benefit? o Why are there stories in the Torah of God punishing those who do not follow commandments? • LECTURE FOUR – PRAYER o Overview of a few misconceptions about Prayer o Philosophy of prayer o Laws of prayer o Power of prayer (holy men’s blessings/gravesite prayers/paying for prayers) • LECTURE FIVE – SUPERSTITION o Overview of a few superstitions in our communities o Can we alter our reality by performing rituals? o Segulot, dybbuks, kapparot, parnassah – what are they? o The Zohar and Kabbalah • LECTURE SIX – STUDYING TORAH vs WORKING o Point out a few misconceptions about Torah study and the working world o Are we obligated to live a life of Torah study? o Yeshiva/Kollel system o Army service • LECTURE SEVEN – CUSTOM vs LAW o Difference between custom and law o Importance of customs o Why has custom -

The Colonizing Self Or, Home and Homelessness in Israel / Palestine

The Colonizing Self Or, HOme and HOmelessness in israel / Palestine Hagar Kotef The Colonizing Self A Theory in Forms Book Series Editors Nancy Rose Hunt and Achille Mbembe Duke University Press / Durham and London / 2020 The Colonizing Self or, home and homelessness in israel/palestine Hagar Kotef © ���� duke university press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Richardson and typeset in Portrait by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Kotef, Hagar, [date] author. Title: The colonizing self : or, home and homelessness in Israel/Palestine / Hagar Kotef. Other titles: Theory in forms. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Series: Theory in forms | Includes biblio- graphical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020017127 (print) | lccn 2020017128 (ebook) isbn 9781478010289 (hardcover) isbn 9781478011330 (paperback) isbn 9781478012863 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Land settlement—West Bank. | Land settlement—Social aspects—West Bank. | Israelis—Colonization—West Bank. | Israelis—Homes and haunts—Social aspects—West Bank. | Israelis—West Bank—Social conditions. Classification: lcc ds110.w47 k684 2020 (print) | lcc ds110.w47 (ebook) ddc 333.3/156942089924—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017127 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017128 Cover art: © Marjan Teeuwen, courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery, NY. The cover image by the Dutch artist Marjan Teeuwen, from a series titled Destroyed House, is of a destroyed house in Gaza, which Teeuwen reassembled and photographed. This form of reclaiming debris and rubble is in conversation with many themes this book foregrounds—from the effort to render destruction visible as a critique of violence to the appropriation of someone else’s home and its destruction as part of one’s identity, national revival, or (as in the case of this image) a professional art exhibition. -

Needs Assessment Study.Pdf

A NATIONAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF MOSQUES ASSOCIATED with Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) & North American Islamic Trust (NAIT) By: Ihsan Bagby CONTENTS Introduction - 3 Basic Demographics - 4 Islamic Approaches - 10 Finances - 11 Imam and Staff - 14 Governance - 21 Women - 26 Mosque Activities and Programs - 30 Training of Mosque Personnel - 37 Grading Various Aspects of the Mosque - 38 Priorities (Open-Ended Question) - 39 Priority Ranking of Various Aspects of the Mosque - 41 Challenges Facing the Mosque - 42 Recommendations to ISNA and NAIT - 44 An Agenda for the American Mosque - 46 Published by the Islamic Society of North America - Copyright © 2013 | Layout & Design by: Abdullah Fadhli Page: 2 INTRODUCTION A NATIONAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF MOSQUES ASSOCIATED with Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) & North American Islamic Trust (NAIT) By: Ihsan Bagby This study is a needs assessment of those The National Needs Assessment consists of mosques that are associated with the two parts. Part One is the Mosque Leader Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) Survey and Part Two is an in-depth study and/or the North American Islamic Trust of three mosques. This document is the (NAIT). The general purpose of any needs report on the Mosque Leader Survey. Part assessment is to determine the strengths, Two of the National Needs Assessment will weaknesses, priorities and needs of an be published separately. institution, and based on the results to make recommendations for strengthening Methodology. Using the criteria for and growing that institution. The goal, establishing whether a mosque is therefore, of this needs assessment is to associated with ISNA/NAIT, a list was understand mosques in order to propose generated which included 331 mosques. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II.