The Destruction of Religious and Cultural Sites I. Introduction The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

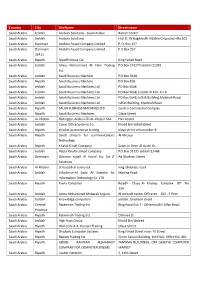

Country City Sitename Street Name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St

Country City SiteName Street name Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions - Saudi Arabia Barom Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Arabian Solutions Hial St. W.Bogddadih AlZabin Cmpound villa 102 Saudi Arabia Damman Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P. O. Box 257 Saudi Arabia Dammam Abdulla Fouad Company Limited P O Box 257 31411 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Riyadh House Est. King Fahad Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Idress Mohammed Ali Fatni Trading P.O.Box 132270 Jeddah 21382 Est. Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machine P.O.Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machine P.O Box 818 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd PO Box 5648 Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Jeddah 21432, K S A Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. PO Box 5648, Juffali Building,Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Jeddah Saudi Business Machines Ltd. Juffali Building, Madinah Road Saudi Arabia Riyadh SAUDI BUSINESS MACHINES LTD. Centria Commercial Complex Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Business Machines Olaya Street Saudi Arabia Al-Khobar Redington Arabia LTD AL-Khobar KSA Hail Center Saudi Arabia Jeddah Canar Office Systems Co Khalid Bin Walid Street Saudi Arabia Riyadh shrakat partnerships trading olaya street villa number 8 Saudi Arabia Riyadh Saudi Unicom for communications Al-Mrouje technology Saudi Arabia Riyadh Khalid Al Safi Company Salah Al-Deen Al-Ayubi St., Saudi Arabia Jeddah Azizia Panda United Company P.O.Box 33333 Jeddah 21448 Saudi Arabia Dammam Othman Yousif Al Yousif Est. for IT Ad Dhahran Street Solutions Saudi Arabia Al Khober al hasoob al asiavy est. king abdulaziz road Saudi Arabia Jeddah EchoServe-Al Sada Al Shamila for Madina Road Information Technology Co. -

Chapter Ii Foreign Policy Foundation of Saudi Arabia and Saudi Arabia Relations with Several International Organizations

CHAPTER II FOREIGN POLICY FOUNDATION OF SAUDI ARABIA AND SAUDI ARABIA RELATIONS WITH SEVERAL INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS This chapter discusses the foreign policy foundation of Saudi Arabia including the general introduction about the State of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Arabia political system, the ruling family, Saudi’s Arabia foreign policy. This chapter also discusses the Saudi Arabia relations with several international organizations. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a country that has many roles, well in the country of the Arabian Peninsula as well as the global environment. The country that still adhere this royal system reserves and abundant oil production as the supporter, the economy of their country then make the country to be respected by the entire of international community. Regardless of the reason, Saudi Arabia also became the Qibla for Muslims around the world because there are two of the holiest city which is Mecca and Medina, at once the birth of Muslim civilization in the era of Prophet Muhammad SAW. A. Geography of Saudi Arabia The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a country located in Southwest Asia, the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula, bordering with the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, as well as Northern Yemen. The extensive coastlines in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea provide a great influence on shipping (especially crude oil) through the Persian Gulf and the Suez Canal. The Kingdom occupies 80 percent of the Arabian Peninsula. Estimates of the Saudi government are at 2,217,949 15 square kilometres, while other leading estimates vary between 2,149,690 and 2,240,000 kilometres. -

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

White Paper Makkah | Retail 2018 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Evolving Dynamics Makkah Retail Overview Summary The holy city of Makkah is currently going through a major strategic development phase to improve connectivity, Ian Albert increase capacity, and enhance the experience of Umrah Regional Director and Hajj pilgrims throughout their stay. Middle East & North Africa This is reflected in the execution of several strategic infrastructure and transportation projects, which have a clear focus on increasing pilgrim capacity and improving connectivity with key projects, including the Holy Haram Expansion, Haramain High- Speed Railway, and King Abdulaziz International Airport. These projects, alongside Vision 2030, are shaping the city’s real estate landscape and stimulating the development of several large real estate projects in their surrounding areas, including King Abdulaziz Road (KAAR), Jabal Omar, Thakher City and Ru’a Al Haram. These projects are creating opportunities for the development of various retail Imad Damrah formats that target pilgrims. Managing Director | Saudi Arabia Makkah has the lowest retail density relative to other primary cities; Riyadh, Jeddah, Dammam Al Khobar and Madinah. With a retail density of c.140 sqm / 1,000 population this is 32% below Madinah which shares the same demographics profile. Upon completion of major transport infrastructure and real estate projects the number of pilgrims is projected to grow by almost 223% from 12.1 million in 2017 up to 39.1 million in 2030 in line with Vision 2030 targets. Importantly the majority of international Pilgrims originate from countries with low purchasing power. Approximately 59% of Hajj and Umrah pilgrims come from countries with GDP/capita below USD 5,000 (equivalent to SAR 18,750). -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

Sayyida Khadija (PBUH)

Sayyida Khadija (PBUH) SAYYIDA KHADIJA (pbuh) Family Tree Qusay Abd Manaf Abdu Uzza Hashim Asad Abdul Khuwaylid * Muttalib * (Khalid) Abdullah Khadija Muhammed * Custodian of the Ka’ba WWW.QFATIMA.COM 11 Key Facts Born in Makka to Khuwaylid & Fatima Bint Za’idah 567 CE Siblings Hala, Usayd & Awwam Children Qasim, Abdullah (died in infancy) Fatima (pbuh). She looked after Zaynab, Umm Kulthum & Ruqayya (daughters of her sister Hala who died) Died in Makka in 620 CE Aged 52 yrs There is Khadija the daughter of Khuwaylid who was the joint custodian of the Ka’ba with Abdul Muttalib; Khadija the successful business women; Khadija the guardian of orphans, Khadija the princess of Makka; Khadija the wife and support of Rasulullah; Khadija the mother of Fatima (pbuh) and then there is Khadija whom Rasulullah (pbuh) said was one of the women of Janna (paradise). She was born in Makka around 567 CE (the date of her birth is not known by any historian) to Khuwaylid and Fatima. Khuwaylid was a successful business man and the joint custodian of the Ka’ba with Abdul Muttalib. Her parents died early within WWW.QFATIMA.COM 2 2 10 years of each other leaving her and her siblings Awwam, Usayd and Hala orphans. She continued the family business of running trade caravans in the Summer to Syria and to Yemen in Winter becoming a successful business woman in her own right. On learning of the excellence of Muhammad (pbuh); she employs him to be her manager. She proposes to him and he accepts. The marriage was a happy one with 3 children – Qasim, Abdullah (Both who died in infancy) and Fatima (pbuh). -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

Annual Report 2019 Contents 1 LETTER FROM CEO 2 2019 HIGHLIGHTS 3 TRADE MISSIONS 4 MEMBERSHIP 6 EVENTS & OUTREACH 13 COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLICATIONS 14 THE COUNCIL Letter from CEO Dear Members of the Business Council, I wish to extend my personal thanks and appreciation to the Board of Directors, Council members and staff of the U.S.- Saudi Arabian Business Council. Having recently joined the Council as Chief Executive Officer, it is my honor to represent you all and recognize our Co-Chairmen Mr. Abdallah Jum’ah, Chairman, The Saudi Investment Bank, and Mr. Steve Demetriou, Chairman and CEO, Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. I want to thank you as well as my colleagues for a warm and productive welcome. When I joined the Council in December 2019, I found a strong organization that had a very active and productive year. Throughout 2019, the Council organized numerous executive networking events, business roundtables, two trade missions, among other activities. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the historic meeting between U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and H.M. King Abdulaziz Al-Saud, an especially significant date to me, my family, and the Business Council. This meeting, aboard the U.S.S. Quincy, became the formal establishment of diplomatic relations between our two great nations. We share a very special bond in not only business and commerce, but also history and friendship. I am particularly pleased to be joining the Business Council at this milestone. Through this special partnership, the Business Council’s underlying mandate it to offer relevant programs and services to benefit you and your company’s market strategies and growth in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. -

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Digital Book

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Introduction The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula. It is about the size of the United States East side of the Mississippi River. It is located in the Middle East, in the western portion of the continent of Asia. The kingdom is bounded by the Gulf of Aqaba and the Red Sea in the west and the Persian Gulf in the east. Can You Find it? Look up Saudi Arabia on the world map. How far is it from your country? https://www.worldatlas.com/ Facts at a Glance Language: Arabic. Religion: Islam Head of State: King Monetary Unit: Saudi Riyal Population: 22,000,000 Arabic Did you know? Arabic is written from right to left It has 28 letters Muslims believe that the Quran was revealed in Arabic by the Angel Gabriel (Jibreel) to Prophet Muhammad peace be Audio File of the Arabic Alphabet upon him. Now and Then Compare and contrast the Arabian Peninsula in 650 CE and how the political map looks now. What are the similarities? Differences? Major Cities Riyadh Mecca Jeddah Medina Where Am I? See if you can label these countries: 1. Kuwait 2.Oman 3.Qatar 4.Saudi Arabia 5.The United Arab Emirates (UAE) 6.Yemen. Can you label the area's major seas and waterways? The Red Sea Gulf of Aden Gulf of Oman The Persian Gulf (also called the Arabian Gulf). Riyadh: [ ree-yahd ] The capital and the largest city. In the older part of the city, the streets are narrow. -

Saudi Arabia.Pdf

A saudi man with his horse Performance of Al Ardha, the Saudi national dance in Riyadh Flickr / Charles Roffey Flickr / Abraham Puthoor SAUDI ARABIA Dec. 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 | Geography . 6 Introduction . 6 Geographical Divisions . 7 Asir, the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Rub al-Khali and the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Hejaz, the Western Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Nejd, the Central Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 The Eastern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Topographical Divisions . .. 9 Deserts and Mountains � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Climate . .. 10 Bodies of Water . 11 Red Sea � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Persian Gulf � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Wadis � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Major Cities . 12 Riyadh � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �12 Jeddah � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Mecca � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad

Journal of Law and Practice Volume 4 Article 3 2011 Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad Charlie Lehmann Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Jaafar-Mohammad, Imani and Lehmann, Charlie (2011) "Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce," Journal of Law and Practice: Vol. 4, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Practice by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Keywords Muslim women--Legal status laws etc., Women's rights--Religious aspects--Islam, Marriage (Islamic law) This article is available in Journal of Law and Practice: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 Jaafar-Mohammad and Lehmann: Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ISLAM REGARDING MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE 4 Wm. Mitchell J. L. & P. 3* By: Imani Jaafar-Mohammad, Esq. and Charlie Lehmann+ I. INTRODUCTION There are many misconceptions surrounding women’s rights in Islam. The purpose of this article is to shed some light on the basic rights of women in Islam in the context of marriage and divorce. This article is only to be viewed as a basic outline of women’s rights in Islam regarding marriage and divorce. -

Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS THE HIGH COST OF CHANGE Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms WATCH The High Cost of Change Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37793 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37793 The High Cost of Change Repression Under Saudi Crown Prince Tarnishes Reforms Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ................................................................................................................7 To the Government of Saudi Arabia ........................................................................................ -

1 Al-Shafi'i, Kitab Al-Umm1 This Is a Template for a Standard Set Of

Al-Shafi’i, Kitab al-Umm1 If any one of you speaks improperly of Muhammad—may God bless This is a template for a standard set of guarantees that the Imam, the and save him—of the Book of God, or of His religion, he forfeits the supreme religious leader of Islam (then the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad), protection [dhimma] of God, of the Commander of the Faithful, and of all might make to Jews and Christians living under his care in a specific city. It dates from the 700s to the 800s. the Muslims; he has contravened the conditions upon which he was given his safe-conduct; his property and his life are at the disposal of the If the Imam wishes to write a document for the poll tax (jizya) of non- Commander of the Faithful, like the property and lives of the people of the Muslims, he should write: house of war [dar al-harb]. In the name of God, the Merciful and the Compassionate. This is a If one of them commits fornication with a Muslim woman or goes document written by the servant of God so-and-so,2 Commander of the through a form of marriage with her or robs a Muslim on the highway or Faithful, on the 2nd of the month of Rabi’l, in the year such-and-such, to subverts a Muslim from his religion or gives aid to those who made war so-and-so son of so-and-so, the Christian, of the descendants of such-and- against the Muslims by fighting with them or by showing them the weak such, of the people of the city of so-and-so.