Early Islamic Architecture in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽabbāsid Art: Squinch Fragmentation As The

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽAbbāsid Art: squinch fragmentation as The structural origin of the muqarnas La tradición sasánida en el arte ʿabbāssí: la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina como origen estructural de la decoración de muqarnas A tradição sassânida na arte abássida: a fragmentação do arco de canto como origem estrutural da decoração das Muqarnas Alicia CARRILLO1 Abstract: Islamic architecture presents a three-dimensional decoration system known as muqarnas. An original system created in the Near East between the second/eighth and the fourth/tenth centuries due to the fragmentation of the squinche, but it was in the fourth/eleventh century when it turned into a basic element, not only all along the Islamic territory but also in the Islamic vocabulary. However, the origin and shape of muqarnas has not been thoroughly considered by Historiography. This research tries to prove the importance of Sasanian Art in the aesthetics creation of muqarnas. Keywords: Islamic architecture – Tripartite squinches – Muqarnas –Sasanian – Middle Ages – ʽAbbāsid Caliphate. Resumen: La arquitectura islámica presenta un mecanismo de decoración tridimensional conocido como decoración de muqarnas. Un sistema novedoso creado en el Próximo Oriente entre los siglos II/VIII y IV/X a partir de la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina, y que en el siglo XI se extendió por toda la geografía del Islam para formar parte del vocabulario del arte islámico. A pesar de su importancia y amplio desarrollo, la historiografía no se ha detenido especialmente en el origen formal de la decoración de muqarnas y por ello, este estudio pone de manifiesto la influencia del arte sasánida en su concepción estética durante el Califato ʿabbāssí. -

Penelitian Individual

3 ii COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH (THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND-STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY WALISONGO) GENDER AND IDENTITY POLITICS (DYNAMICS OF MOSLEM WOMEN IN AUSTRALIA) Researchers: Misbah Zulfa Elizabeth Lift Anis Ma’shumah Nadiatus Salama Academic Advisor: Dr. Morgan Brigg Dr. Lee Wilson Funded by DIPA UIN Walisongo 2015 iii iv PREFACE This research, entitled Gender and Identity Politics (Dynamics of Moslem Women in Australia) is implemented as the result of cooperation between State Islamic University Walisongo and The University of Queensland (UQ) Brisbane Australia for the second year. With the completion of this research, researchers would like to say thank to several people who have helped in the processes as well as in the completion of the research . They are 1 Rector of State Islamic University Walisongo 2. Chairman of Institute for Research and Community Service (LP2M) State Islamic University Walisongo 3. Chancellor of The UQ 4. Academic advisor from The UQ side : Dr. Morgan Brigg and Dr. Lee Wilson 5. All those who have helped the implementation of this study Finally , we must state that these report has not been perfect . We are sure there are many limitedness . Therefore, we are happy to accept criticism , advice and go for a more refined later . Semarang, December 2015 Researchers v vi TABLE OF CONTENT PREFACE — v TABLE OF CONTENT — vi Chapter I. Introduction A. Background — 1 B. Research Question — 9 C. Literature Review — 9 D. Theoretical Framework — 14 E. Methods — 25 Chapter II. Identity Politics and Minority-Majority Relation among Women A. Definition of Identity Politics — 29 B. Definition of Majority-Minority — 36 C. -

Treasures of Iran

Treasures of Iran 15 Days Treasures of Iran Home to some of the world's most renowned and best-preserved archaeological sites, Iran is a mecca for art, history, and culture. This 15-day itinerary explores the fascinating cities of Tehran, Shiraz, Yazd, and Isfahan, and showcases Iran's rich, textured past while visiting ancient ruins, palaces, and world-class museums. Wander vibrant bazaars, behold Iran's crown jewels, and visit dazzling mosques adorned with blue and aqua tile mosaics. With your local guide who has led trips here for over 23 years, be one of the few lucky travelers to discover this unique destination! Details Testimonials Arrive: Tehran, Iran “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me Depart: Tehran, Iran —widening my view of the world and its peoples.” Duration: 15 Days Jane B. Group Size: 6-16 Guests "Our trip to Iran was an outstanding Minimum Age: 16 Years Old success! Both of our guides were knowledgeable and well prepared, and Activity Level: Level 2 played off of each other, incorporating . lectures, poetry, literature, music, and historical sights. They were generous with their time and answered questions non-stop. Iran is an important country, strategically situated, with 3,000+ years of culture and history." Joseph V. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek is an expert in Iran Our team of local guides are true This journey exposes travelers travel, with over five years' experts, including Saeid Haji- to the hospitality of Iranian experience taking small Hadi (aka Hadi), who has been people, while offering groups into the country. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Iran Eco Adventure Tours

Iran Eco Adventure TOURS “My mother was one of the first professional female rock climbers in Iran and she was the memberof first Iranian student team to climb Mount Everest.She introduced my uncle to mountaineering then my uncle in turn converted other members of the family.” SahandAghdaie recalls as he explains the backstory of Iran Eco Adventure. For Sahand, the founder and CEO of Iran Eco Adventure Tours Co., mountaineering and nature are like family heirlooms. Thus, he joined his uncle in 2006 to bring into being one of the pioneer Iranian companies in Eco adventures. Iran Eco Adventure is the brand name of incoming tours and a division of Spilet Eco Adventures Co. It’s an Iran based company and for over 10 years we’ve been made memories and trips for people who love outdoor activities and hiking, have a passion for travel and a bucket list of exciting adventures. Iran Eco Adventure Our travel experience runs deep, from years mountaineering and traveling in nature of Iran to research trips and just bouncing around every corner of the country. This deep experience is the reason behind our pioneering approach to winning itineraries. Whether you’ve taken many trips, or you’re tying up for the first time, we design and offer everything in the tour program according to your needs. Our tours offer variety of adventure activities ranging from hiking, trekking and biking to alpine skiing and desert safari. Giving you the joy of adventure in numerous locations of our beautiful country under our proficiency steam is what our company mission is all about and we pride ourselves on our knowledge of destinations and our dedication to nature. -

Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N

Exhibit A LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N. Sheridan Rd. Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, August 7, 2014 CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is re- sponsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city per- mits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recom- mendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment dur- ing the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 CAIRO SUPPER CLUB BUILDING (ORIGINALLY WINSTON BUILDING) 4015-4017 N. SHERIDAN RD. BUILT: 1920 ARCHITECT: PAUL GERHARDT, SR. Located in the Uptown community area, the Cairo Supper Club Building is an unusual building de- signed in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, rarely used for Chicago buildings. This one-story commercial building is clad with multi-colored terra cotta, created by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company and ornamented with a variety of ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus-decorated col- umns and a concave “cavetto” cornice with a winged-scarab medallion. -

Needs Assessment Study.Pdf

A NATIONAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF MOSQUES ASSOCIATED with Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) & North American Islamic Trust (NAIT) By: Ihsan Bagby CONTENTS Introduction - 3 Basic Demographics - 4 Islamic Approaches - 10 Finances - 11 Imam and Staff - 14 Governance - 21 Women - 26 Mosque Activities and Programs - 30 Training of Mosque Personnel - 37 Grading Various Aspects of the Mosque - 38 Priorities (Open-Ended Question) - 39 Priority Ranking of Various Aspects of the Mosque - 41 Challenges Facing the Mosque - 42 Recommendations to ISNA and NAIT - 44 An Agenda for the American Mosque - 46 Published by the Islamic Society of North America - Copyright © 2013 | Layout & Design by: Abdullah Fadhli Page: 2 INTRODUCTION A NATIONAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT OF MOSQUES ASSOCIATED with Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) & North American Islamic Trust (NAIT) By: Ihsan Bagby This study is a needs assessment of those The National Needs Assessment consists of mosques that are associated with the two parts. Part One is the Mosque Leader Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) Survey and Part Two is an in-depth study and/or the North American Islamic Trust of three mosques. This document is the (NAIT). The general purpose of any needs report on the Mosque Leader Survey. Part assessment is to determine the strengths, Two of the National Needs Assessment will weaknesses, priorities and needs of an be published separately. institution, and based on the results to make recommendations for strengthening Methodology. Using the criteria for and growing that institution. The goal, establishing whether a mosque is therefore, of this needs assessment is to associated with ISNA/NAIT, a list was understand mosques in order to propose generated which included 331 mosques. -

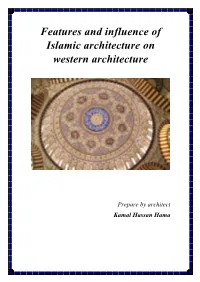

Features and Influence of Islamic Architecture on Western Architecture

Features and influence of Islamic architecture on western architecture Prepare by architect Kamal Hassan Hama List of content . Historical overview . The most important elements of Islamic architecture . Influences of Islamic architecture . Features of Islamic architecture and arts . The impact of Islamic architecture on Western architecture Historical overview Islamic architec The characteristics and characteristics of Islamic architecture were greatly influenced by the Islamic religion and the scientific renaissance that followed it. It differs from one region to another according to the weather and the previous architectural and civilizational legacy in the region, as the open courtyard is spread in the Levant, Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula, while it disappeared in Turkey as a result of the cold weather and in Yemen due to the architectural legacy. We also see the development of form and function over time and the change in the political, living and cultural conditions of the population ture is the structural characteristics that Muslims used to be their identity, and that architecture arose thanks to Islam in the areas that it reached such as the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, the Levant, the Maghreb, Turkey, Iran and others, in addition to the regions that ruled for long periods such as Andalusia (now Spain) and India. The most important elements of Islamic architecture Minarets Domes Contracts Saucer Niche Basement Mashrabiyas Columns and crowns Ornaments, decorations and muqarnas Minarets Minarets appeared in Islamic architecture -

Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bet HaMikdash ; "The Holy House"), refers to Part of a series of articles on ,שדקמה תיב :The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple (Hebrew a series of structures located on the Temple Mount (Har HaBayit) in the old city of Jerusalem. Historically, two Jews and Judaism navigation temples were built at this location, and a future Temple features in Jewish eschatology. According to classical Main page Jewish belief, the Temple (or the Temple Mount) acts as the figurative "footstool" of God's presence (Heb. Contents "shechina") in the physical world. Featured content Current events The First Temple was built by King Solomon in seven years during the 10th century BCE, culminating in 960 [1] [2] Who is a Jew? ∙ Etymology ∙ Culture Random article BCE. It was the center of ancient Judaism. The Temple replaced the Tabernacle of Moses and the Tabernacles at Shiloh, Nov, and Givon as the central focus of Jewish faith. This First Temple was destroyed by Religion search the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Construction of a new temple was begun in 537 BCE; after a hiatus, work resumed Texts 520 BCE, with completion occurring in 516 BCE and dedication in 515. As described in the Book of Ezra, Ethnicities Go Search rebuilding of the Temple was authorized by Cyrus the Great and ratified by Darius the Great. Five centuries later, Population this Second Temple was renovated by Herod the Great in about 20 BCE. -

Two Queens of ^Baghdad Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of ^Baghdad oi.uchicago.edu Courtesy of Dr. Erich Schmidt TOMB OF ZUBAIDAH oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of Baghdad MOTHER AND WIFE OF HARUN AL-RASH I D By NABIA ABBOTT ti Vita 0CCO' cniia latur THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press • Chicago 37 Agent: Cambridge University Press • London Copyright 1946 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1946. Composed and printed by The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu Preface HE historical and legendary fame of Harun al- Rashld, the most renowned of the caliphs of Bagh dad and hero of many an Arabian Nights' tale, has ren dered him for centuries a potent attraction for his torians, biographers, and litterateurs. Early Moslem historians recognized a measure of political influence exerted on him by his mother Khaizuran and by his wife Zubaidah. His more recent biographers have tended either to exaggerate or to underestimate the role of these royal women, and all have treated them more or less summarily. It seemed, therefore, desirable to break fresh ground in an effort to uncover all the pertinent his torical materials on the two queens themselves, in order the better to understand and estimate the nature and the extent of their influence on Harun and on several others of the early cAbbasid caliphs. As the work progressed, first Khaizuran and then Zubaidah emerged from the privacy of the royal harem to the center of the stage of early cAbbasid history. -

Aws Edition 1, 2009

Appendix B WS Edition 1, 2009 - [WI WebDoc [10/09]] A 6 Interior and Exterior Millwork © 2009, AWI, AWMAC, WI - Architectural Woodwork Standards - 1st Edition, October 1, 2009 B (Appendix B is not part of the AWS for compliance purposes) 481 Appendix B 6 - Interior and Exterior Millwork METHODS OF PRODUCTION Flat Surfaces: • Sawing - This produces relatively rough surfaces that are not utilized for architectural woodwork except where a “rough sawn” texture or nish is desired for design purposes. To achieve the smooth surfaces generally required, the rough sawn boards are further surfaced by the following methods: • Planing - Sawn lumber is passed through a planer or jointer, which has a revolving head with projecting knives, removing a thin layer of wood to produce a relatively smooth surface. • Abrasive Planing - Sawn lumber is passed through a powerful belt sander with tough, coarse belts, which remove the rough top surface. Moulded Surfaces: Sawn lumber is passed through a moulder or shaper that has knives ground to a pattern which produces the moulded pro[le desired. SMOOTHNESS OF FLAT AND MOULDED SURFACES Planers and Moulders: The smoothness of surfaces which have been machine planed or moulded is determined by the closeness of the knife cuts. The closer the cuts to each other (i.e., the more knife cuts per inch [KCPI]) the closer the ridges, and therefore the WS Edition 1, 2009 - [WI WebDoc [10/09]] smoother the resulting appearance. A Sanding and Abrasives: Surfaces can be further smoothed by sanding. Sandpapers come in grits from coarse to [ne and are assigned ascending grit numbers. -

The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol

The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.nuhmafricanus3 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 Alternative title The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained Author/Creator Leo Africanus Contributor Pory, John (tr.), Brown, Robert (ed.) Date 1896 Resource type Books Language English, Italian Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast;Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu, Southern Swahili Coast Source Northwestern University Libraries, G161 .H2 Description Written by al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed al-Wezaz al-Fasi, a Muslim, baptised as Giovanni Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus.