So, Says I, We Are a Brutal Kind”I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Rhetoric: the Art of Thinking Being

BLACK RHETORIC: THE ART OF THINKING BEING by APRIL LEIGH KINKEAD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2013 Copyright © by April Leigh Kinkead 2013 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the guidance, advice, and support of others. I would like to thank my advisor, Cedrick May, for his taking on the task of directing my dissertation. His knowledge, advice, and encouragement helped to keep me on track and made my completing this project possible. I am grateful to Penelope Ingram for her willingness to join this project late in its development. Her insights and advice were as encouraging as they were beneficial to my project’s aims. I am indebted to Kevin Gustafson, whose careful reading and revisions gave my writing skills the boost they needed. I am a better writer today thanks to his teachings. I also wish to extend my gratitude to my school colleagues who encouraged me along the way and made this journey an enjoyable experience. I also wish to thank the late Emory Estes, who inspired me to pursue graduate studies. I am equally grateful to Luanne Frank for introducing me to Martin Heidegger’s theories early in my graduate career. This dissertation would not have come into being without that introduction or her guiding my journey through Heidegger’s theories. I must also thank my family and friends who have stood by my side throughout this long journey. -

Chapter Two: the Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era

Chapter Two: The Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era Contents 2.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 30 2.1.1 Learning Outcomes ....................................................................................... 30 2.2 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: PORTUGAL AND SPAIN ........................... 31 2.2.1 Portugal Initiates the Age of Discovery ............................................................. 31 2.2.2 The Spanish in the Age of Discovery ................................................................ 33 2.2.3 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 35 Key Concepts ....................................................................................................35 Test Yourself ...................................................................................................... 36 2.3 ASIA IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: CHINESE EXPANSION DURING THE MING DYNASTY 37 2.3.1 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 40 Key Concepts ................................................................................................... 40 Test Yourself .................................................................................................... 41 2.4 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: ENGLAND AND FRANCE ........................ 41 2.4.1 England and France at War .......................................................................... -

African Mythology a to Z

African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z Celtic Mythology A to Z Chinese Mythology A to Z Egyptian Mythology A to Z Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z Japanese Mythology A to Z Native American Mythology A to Z Norse Mythology A to Z South and Meso-American Mythology A to Z MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION 8 Patricia Ann Lynch Revised by Jeremy Roberts [ African Mythology A to Z, Second Edition Copyright © 2004, 2010 by Patricia Ann Lynch All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Chelsea House 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lynch, Patricia Ann. African mythology A to Z / Patricia Ann Lynch ; revised by Jeremy Roberts. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60413-415-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Mythology—African. 2. Encyclopedias—juvenile. I. Roberts, Jeremy, 1956- II. Title. BL2400 .L96 2010 299.6' 11303—dc22 2009033612 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web at http://www.chelseahouse.com Text design by Lina Farinella Map design by Patricia Meschino Composition by Mary Susan Ryan-Flynn Cover printed by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Bood printed and bound by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Date printed: March 2010 Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Miszelle Warrior-Women of Dahomey

Miszelle Martin van Creveld Warrior-Women of Dahomey Ever since America's armed forces were put on a volunteer basis in 1971-72, the bar- riers which traditionally kept women out of the military have been crumbling. In January 2000 the European Court in its wisdom ruled that the Bundeswehr's pol- icy of keeping out women was against European law; thus probably hastening the end of conscription in Germany and certainly making sure that the subject will continue to be debated for years to come. In this broad context, the warrior women of Dahomey are interesting on two counts. First, they are sometimes regarded as living proof that women can fight and have fought. Second, some radical feminists have pointed to the Dahomean she-fighters as a model of prowess; one which oth- er women, struggling to liberate themselves from the yoke of »patriarchy«, should do well to take as their model. On the other hand, it is this author's experience that when most people, femi- nists and miUtary historians included, are asked to explain what they know about the warrior-women in question they respond with an embarrassed silence. Ac- cordingly, my purpose is to use the available sources - all of them European, and some quite fanciful - in order to provide a brief survey of the facts. Those who want to use those facts either for arguing that women can and should participate in combat or for wider feminist purposes, welcome. This Story opens towards the end of the sixteenth Century, a period when Euro- peans traveUing to other continents competed with each other as to who could bring back the strängest and most fanciful tales. -

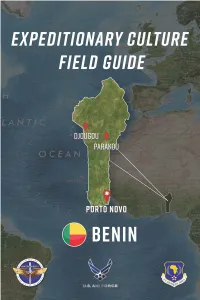

The Kingdom of Dahomey

THE KINGDOM OF DAHOMEY J. LOMBARD In earlier times 'Danhomé' was the name given to the fabulous kingdom of Abomey; and it is by this name that the modern republic is known. Sorne of the first European travelIers visited the country and left eye-witness accounts of the splendour and organization of the royal court. An employee of the Mrican Company, BulIfinch Lambe, visited the Dahomey capital in 1724. Henceforth innumerable missions-English for the most part arrived at the capital of the Abomey kings. Norris (in 1772 and 1773), Forbes, Richard Burton, and Dr. Répin(aIl in the nineteenth century) were a few of the travelIers who left detailed accounts of their journeys. On the eve of European penetration the Dahomey kingdom stretched from the important coastal ports of Whydah and Cotonou to the eighth paralIel, excluding Savé and Savalou. Savalou formed a smalI alIied kingdom. East to west, it extended from Ketu, on the present Nigerian border, to the district around Atakpame in modern Togo. Towns like AlIada (the capital of the former kingdom of Ardra), Zagnanado, Parahoue (or Aplahoué), and Dassa-Zoumé came under the suzerainty of the Dahomean kings. Even the Porto Novo kingdom was at one time threatened by Dahomean forces at the time of the treaty agreeing to a French protectorate. The Dahomey kingdom thus stretched almost two hundred miles from north to south, and one hundred miles from east to west. Its population has been estimated roughly at two hundred thousand. The founding of the Abomey kingdom dates from about the beginning of the seventeenth century. -

Africana Studies Review

AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ON THE COVER DETAIL FROM A PIECE OF THE WOODEN QUILTS™ COLLECTION BY NEW ORLEANS- BORN ARTIST AND HOODOO MAN, JEAN-MARCEL ST. JACQUES. THE COLLECTION IS COMPOSED ENTIRELY OF WOOD SALVAGED FROM HIS KATRINA-DAMAGED HOME IN THE TREME SECTION OF THE CITY. ST. JACQUES CITES HIS GRANDMOTHER—AN AVID QUILTER—AND HIS GRANDFATHER—A HOODOO MAN—AS HIS PRIMARY INFLUENCES AND TELLS OF HOW HEARING HIS GRANDMOTHER’S VOICE WHISPER, “QUILT IT, BABY” ONE NIGHT INSPIRED THE ACCLAIMED COLLECTION. PIECES ARE NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM AND OTHER VENUES. READ MORE ABOUT ST. JACQUES’ JOURNEY BEGINNING ON PAGE 75 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY DEANNA GLORIA LOWMAN AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ISSN 1555-9246 AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Africana Studies Review ....................................................................... 4 Editorial Board ....................................................................................................... 5 Introduction to the Spring 2019 Issue .................................................................... 6 Funlayo E. Wood Menzies “Tribute”: Negotiating Social Unrest through African Diasporic Music and Dance in a Community African Drum and Dance Ensemble .............................. 11 Lisa M. Beckley-Roberts Still in the Hush Harbor: Black Religiosity as Protected Enclave in the Contemporary US ................................................................................................ 23 Nzinga Metzger The Tree That Centers the World: The Palm Tree as Yoruba Axis Mundi ........ -

![Dogon Restudied: a Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [And Comments and Replies]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4277/dogon-restudied-a-field-evaluation-of-the-work-of-marcel-griaule-and-comments-and-replies-1654277.webp)

Dogon Restudied: a Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [And Comments and Replies]

Dogon Restudied: A Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [and Comments and Replies] Walter E. A. van Beek; R. M. A. Bedaux; Suzanne Preston Blier; Jacky Bouju; Peter Ian Crawford; Mary Douglas; Paul Lane; Claude Meillassoux Current Anthropology, Vol. 32, No. 2. (Apr., 1991), pp. 139-167. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0011-3204%28199104%2932%3A2%3C139%3ADRAFEO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O Current Anthropology is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. -

Stewardship in West African Vodun: a Case Study of Ouidah, Benin

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2010 STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN HAYDEN THOMAS JANSSEN The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation JANSSEN, HAYDEN THOMAS, "STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN" (2010). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 915. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/915 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STEWARDSHIP IN WEST AFRICAN VODUN: A CASE STUDY OF OUIDAH, BENIN By Hayden Thomas Janssen B.A., French, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2003 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Geography The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2010 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Jeffrey Gritzner, Chairman Department of Geography Sarah Halvorson Department of Geography William Borrie College of Forestry and Conservation Tobin Shearer Department of History Janssen, Hayden T., M.A., May 2010 Geography Stewardship in West African Vodun: A Case Study of Ouidah, Benin Chairman: Jeffrey A. Gritzner Indigenous, animistic religions inherently convey a close relationship and stewardship for the environment. This stewardship is very apparent in the region of southern Benin, Africa. -

Palace Sculptures of Abomey Combines Color Photographs of the Bas-Reliefs with a Lively History of Dahomey, Complemented by Rare Historical Images

114 SUGGESTED READING Suggested Reading Assogba, Romain-Philippe. Le Musee d'Histoire Moss, Joyce, and George Wilson. Peoples de Ouidah: Decouverte de la COte des Esc/aves. of the Wo rld: Africans South of the Sahara. Ouidah, Benin: Editions Saint Michel, 1994. Detroit and London: Gale Research, 1991. Beckwith, Carol, and Angela Fisher. Pliya, Jean. Dahomey. Issy-les-Moulineaux, "The African Roots of Vo odoo." Na tional France: Classiques Africains, 1975. Geographic Magazine 88 (August 1995): 102-13. Ronen, Dov. Dahomey: Between Tradition and Blier, Suzanne Preston. African Vo dun: Art, Modernity. Ithaca, N.Y., and London: Cornell Psychology, and Power. Chicago: University of University Press, 1975. Chicago Press, 1995. Waterlot, E. G. Les bas-reliefs des Palais Royaux ___. "The Musee Historique in Abomey: d'Abomey. Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, 1926. Art, Politics, and the Creation of an African Museum." In Arte in Africa 2. Florence: Centro In addition to the scholarly works listed above, di Studi di Storia delle Arte Africane, 1991. interested readers may consult Archibald ___. "King Glele of Danhome: Divination Dalzel's account of Dahomey in the late eigh Portraits of a Lion King and Man of Iron." teenth century, The History of Dahomy: African Arts 23, no. 4 (October 1990): 42-53, An Inland Kingdom ofAf rica (1793; reprint, London, Frank Cass and Co., 1967), and Sir 93-94· Richard Burton's A Mission to Gelele, King of "The Place Where Vo dun Was Born." Dahome (1864; reprint, London, Routledge & Na tural History Magazine 104 (October 1995): Kegan Paul, 1966); both offer historical 40-49· European perspectives on the Dahomey king Decalo, Samuel. -

The Land Has Changed: History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2010 The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria Korieh, Chima J. University of Calgary Press Chima J. Korieh. "The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria". Series: Africa, missing voices series 6, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48254 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE LAND HAS CHANGED History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria Chima J. Korieh ISBN 978-1-55238-545-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

ECFG-Benin-Apr-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Beninese medics perform routine physical examinations on local residents of Wanrarou, Benin). ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Benin Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Benin, focusing on unique cultural features of Beninese society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: Beninese Army Soldier practices baton strikes during peacekeeping training with US Marine in Bembereke, Benin). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

History 377: History of Africa, 1500-1870

History 377: History of Africa, 1500‐1870 Fall 2009 Neil Kodesh MWF 11.00‐11.55 [email protected] 1131 Humanities Office Hours: Monday, 1.00‐2.30 TA: Sean Bloch 5115 Humanities Mansa Musa, King of Mali Welcome to History 377. The course provides a survey of the cultural and social history of Africa south of the Sahara from approximately 1500‐1870. Because there is so much to learn about Africa and Africans during this period, we cannot strive for exhaustive coverage. However, we will visit almost every major historical region of sub‐Sarahan Africa at least once during the semester and will focus on several important themes in the history of the continent. The first part of the course focuses on the historical development of African societies prior to the rise of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades. We will then explore the origins of the Atlantic slave trade and its impact on Africa. Finally, we will complete the course by examining the momentous transformations in sub‐Saharan Africa during ʺthe long 19th century,ʺ including the dramatic growth of the Indian Ocean slave trade, the establishment of European settlements in South Africa, and the expansion of European influence in other parts of the continent during the period leading up to the formal establishment of colonial rule. 1 Required Readings: The following books are available for purchase at the University Bookstore and are also on reserve at Helen C. White: Lisa A. Lindsay, Captives as Commodities: The Transatlantic Slave Trade D.T. Niane, Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali Stephanie Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora I have also collected a set of readings for you to purchase from the copy center in the Humanities building (room 1650) and placed readings on reserve at College Library.