The Kingdom of Dahomey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

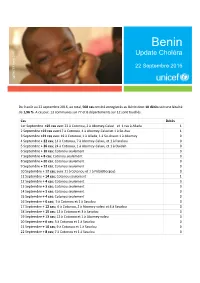

Update Choléra

Benin Update Choléra 22 Septembre 2016 @UNICEF Benin 2016 Benin @UNICEF Du 9 août au 22 septembre 2016, au total, 508 cas ont été enregistrés au Bénin dont 10 décès soit une létalité de 1,96 %. A ce jour, 13 communes sur 77 et 6 départements sur 12 sont touchés. Cas Décès 1er Septembre +25 cas avec 22 à Cotonou, 2 à Abomey-Calavi et 1 cas à Allada 1 2 Septembre +22 cas avec17 à Cotonou, 4 à Abomey-Calavi et 1 à So-Ava 1 3 Septembre +21 cas avec 19 à Cotonou, 1 à Allada, 1 à So-Ava et 1 à Abomey 0 4 Septembre + 22 cas; 14 à Cotonou, 7 à Abomey-Calavi, et 1 à Parakou 0 5 Septembre + 26 cas; 24 à Cotonou, 1 à Abomey-Calavi, et 1 à Ouidah 0 6 Septembre + 10 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 7 Septembre + 8 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 8 Septembre + 20 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 9 Septembre + 12 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 10 Septembre + 12 cas; avec 11 à Cotonou et 1 à Ndali(Borgou) 0 11 Septembre + 14 cas; Cotonou seulement 1 12 Septembre + 4 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 13 Septembre + 3 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 14 Septembre + 3 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 15 Septembre + 4 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 16 Septembre + 6 cas; 5 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 17 Septembre + 12 cas; 6 à Cotonou, 2 à Abomey-calavi et 4 à Savalou 0 18 Septembre + 15 cas; 12 à Cotonou et 3 à Savalou 0 19 Septembre + 13 cas; 12 à Cotonou et 1 à Abomey-calavi 0 20 Septembre + 6 cas; 5 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 21 Septembre + 10 cas; 9 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 22 Septembre + 8 cas; 7 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 1. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Black Rhetoric: the Art of Thinking Being

BLACK RHETORIC: THE ART OF THINKING BEING by APRIL LEIGH KINKEAD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2013 Copyright © by April Leigh Kinkead 2013 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the guidance, advice, and support of others. I would like to thank my advisor, Cedrick May, for his taking on the task of directing my dissertation. His knowledge, advice, and encouragement helped to keep me on track and made my completing this project possible. I am grateful to Penelope Ingram for her willingness to join this project late in its development. Her insights and advice were as encouraging as they were beneficial to my project’s aims. I am indebted to Kevin Gustafson, whose careful reading and revisions gave my writing skills the boost they needed. I am a better writer today thanks to his teachings. I also wish to extend my gratitude to my school colleagues who encouraged me along the way and made this journey an enjoyable experience. I also wish to thank the late Emory Estes, who inspired me to pursue graduate studies. I am equally grateful to Luanne Frank for introducing me to Martin Heidegger’s theories early in my graduate career. This dissertation would not have come into being without that introduction or her guiding my journey through Heidegger’s theories. I must also thank my family and friends who have stood by my side throughout this long journey. -

Chapter Two: the Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era

Chapter Two: The Global Context: Asia, Europe, and Africa in the Early Modern Era Contents 2.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 30 2.1.1 Learning Outcomes ....................................................................................... 30 2.2 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: PORTUGAL AND SPAIN ........................... 31 2.2.1 Portugal Initiates the Age of Discovery ............................................................. 31 2.2.2 The Spanish in the Age of Discovery ................................................................ 33 2.2.3 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 35 Key Concepts ....................................................................................................35 Test Yourself ...................................................................................................... 36 2.3 ASIA IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: CHINESE EXPANSION DURING THE MING DYNASTY 37 2.3.1 Before You Move On... ................................................................................... 40 Key Concepts ................................................................................................... 40 Test Yourself .................................................................................................... 41 2.4 EUROPE IN THE AGE OF DISCOVERY: ENGLAND AND FRANCE ........................ 41 2.4.1 England and France at War .......................................................................... -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Rapport Final De L'enquete Steps Au Benin

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN MINISTERE DE LA SANTE Direction Nationale de la Protection Sanitaire Programme National de Lutte contre les Maladies Non Transmissibles RAPPORT FINAL DE L’ENQUETE STEPS AU BENIN Juin 2008 EQUIPE DE REDACTION Pr. HOUINATO Dismand Coordonnateur National / PNLMNT Dr SEGNON AGUEH Judith A. Médecin Epidémiologiste / PNLMNT Pr. DJROLO François Point focal diabète /PNLMNT Dr DJIGBENNOUDE Oscar Médecin Santé Publique/ PNLMNT i Sommaire RESUME ...........................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................... 2 2 OBJECTIFS ................................................................................................ 5 3 CADRE DE L’ETUDE: (étendue géographique).........................................7 4 METHODE ............................................................................................... 16 5 RESULTATS ............................................................................................ 23 6 Références bibliographiques...................................................................... 83 7 Annexes ii Liste des tableaux Tableau I: Caractéristiques sociodémographiques des sujets enquêtés au Bénin en 2008..... 23 Tableau II: Répartition des sujets enquêtés en fonction de leur niveau d’instruction, activité professionnelle et département au Bénin en 2008. ................................................................ 24 Tableau III : Répartition des consommateurs -

African Mythology a to Z

African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z Celtic Mythology A to Z Chinese Mythology A to Z Egyptian Mythology A to Z Greek and Roman Mythology A to Z Japanese Mythology A to Z Native American Mythology A to Z Norse Mythology A to Z South and Meso-American Mythology A to Z MYTHOLOGY A TO Z African Mythology A to Z SECOND EDITION 8 Patricia Ann Lynch Revised by Jeremy Roberts [ African Mythology A to Z, Second Edition Copyright © 2004, 2010 by Patricia Ann Lynch All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Chelsea House 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lynch, Patricia Ann. African mythology A to Z / Patricia Ann Lynch ; revised by Jeremy Roberts. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60413-415-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Mythology—African. 2. Encyclopedias—juvenile. I. Roberts, Jeremy, 1956- II. Title. BL2400 .L96 2010 299.6' 11303—dc22 2009033612 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web at http://www.chelseahouse.com Text design by Lina Farinella Map design by Patricia Meschino Composition by Mary Susan Ryan-Flynn Cover printed by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Bood printed and bound by Bang Printing, Brainerd, MN Date printed: March 2010 Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Miszelle Warrior-Women of Dahomey

Miszelle Martin van Creveld Warrior-Women of Dahomey Ever since America's armed forces were put on a volunteer basis in 1971-72, the bar- riers which traditionally kept women out of the military have been crumbling. In January 2000 the European Court in its wisdom ruled that the Bundeswehr's pol- icy of keeping out women was against European law; thus probably hastening the end of conscription in Germany and certainly making sure that the subject will continue to be debated for years to come. In this broad context, the warrior women of Dahomey are interesting on two counts. First, they are sometimes regarded as living proof that women can fight and have fought. Second, some radical feminists have pointed to the Dahomean she-fighters as a model of prowess; one which oth- er women, struggling to liberate themselves from the yoke of »patriarchy«, should do well to take as their model. On the other hand, it is this author's experience that when most people, femi- nists and miUtary historians included, are asked to explain what they know about the warrior-women in question they respond with an embarrassed silence. Ac- cordingly, my purpose is to use the available sources - all of them European, and some quite fanciful - in order to provide a brief survey of the facts. Those who want to use those facts either for arguing that women can and should participate in combat or for wider feminist purposes, welcome. This Story opens towards the end of the sixteenth Century, a period when Euro- peans traveUing to other continents competed with each other as to who could bring back the strängest and most fanciful tales. -

Africana Studies Review

AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ON THE COVER DETAIL FROM A PIECE OF THE WOODEN QUILTS™ COLLECTION BY NEW ORLEANS- BORN ARTIST AND HOODOO MAN, JEAN-MARCEL ST. JACQUES. THE COLLECTION IS COMPOSED ENTIRELY OF WOOD SALVAGED FROM HIS KATRINA-DAMAGED HOME IN THE TREME SECTION OF THE CITY. ST. JACQUES CITES HIS GRANDMOTHER—AN AVID QUILTER—AND HIS GRANDFATHER—A HOODOO MAN—AS HIS PRIMARY INFLUENCES AND TELLS OF HOW HEARING HIS GRANDMOTHER’S VOICE WHISPER, “QUILT IT, BABY” ONE NIGHT INSPIRED THE ACCLAIMED COLLECTION. PIECES ARE NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM AND OTHER VENUES. READ MORE ABOUT ST. JACQUES’ JOURNEY BEGINNING ON PAGE 75 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY DEANNA GLORIA LOWMAN AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ISSN 1555-9246 AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Africana Studies Review ....................................................................... 4 Editorial Board ....................................................................................................... 5 Introduction to the Spring 2019 Issue .................................................................... 6 Funlayo E. Wood Menzies “Tribute”: Negotiating Social Unrest through African Diasporic Music and Dance in a Community African Drum and Dance Ensemble .............................. 11 Lisa M. Beckley-Roberts Still in the Hush Harbor: Black Religiosity as Protected Enclave in the Contemporary US ................................................................................................ 23 Nzinga Metzger The Tree That Centers the World: The Palm Tree as Yoruba Axis Mundi ........ -

![Dogon Restudied: a Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [And Comments and Replies]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4277/dogon-restudied-a-field-evaluation-of-the-work-of-marcel-griaule-and-comments-and-replies-1654277.webp)

Dogon Restudied: a Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [And Comments and Replies]

Dogon Restudied: A Field Evaluation of the Work of Marcel Griaule [and Comments and Replies] Walter E. A. van Beek; R. M. A. Bedaux; Suzanne Preston Blier; Jacky Bouju; Peter Ian Crawford; Mary Douglas; Paul Lane; Claude Meillassoux Current Anthropology, Vol. 32, No. 2. (Apr., 1991), pp. 139-167. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0011-3204%28199104%2932%3A2%3C139%3ADRAFEO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O Current Anthropology is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. -

Terms of Reference

Telephone: + 49 (0) 228 815 2800 Fax: + 49 (0) 228 815 2898/99 Email: [email protected] TERMS OF REFERENCE National consultant – Support to GCF project document design for a gender-responsive LDN Transformative Project - in Benin Consultancy reference number: CCD/20/GM/33 Background The Global Mechanism is an institution of the UNCCD, mandated to assist countries in the mobilization of financial resources from the public and private sector for activities that prevent, control or reverse desertification, land degradation and drought. As the operational arm of the convention, the Global Mechanism supports countries to translate the Convention into action. In September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, including goal 15, which aims to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”. The main expected result is defined under target 15.3 to “combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world” by 2030. In September 2017, the 13th session of the Conference of Parties (COP) of the UNCCD emphasized the critical role of Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) Transformative Projects and Programmes for the implementation of the Convention. This has been reaffirmed at the 14th session of the COP in New Delhi in September 2019. The government of Benin has adopted LDN targets at the highest level in 2017 and is now in the process of designing a gender responsive LDN Transformative Project/Programme to translate its voluntary LDN targets into concrete implementation.