Spear-Carrier in a Backwater War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Twenty-Five Years Ahead of Its Time: the American Aerial Torpedo in World War I

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AHEAD OF ITS TIME: THE AMERICAN AERIAL TORPEDO IN WORLD WAR I Michael H. Taint, Lt. Colonel, USAF (Ret) Independent Scholar To the modern-day public, no weapon system is more evocative of American high technology than the “drone” or, more formally, the “Unmanned Aerial System” (UAS) or “Remotely Piloted Aircraft” (RPA). UASs in the last two decades have been deployed extensively through southwest Asia and appear almost daily in news reports. Few realize they were pioneered a century ago and nearly took their place alongside the tank, submarine, chemical weapons and fighter aircraft as an important technological breakthrough of World War I. This paper explores the development and testing of the first American drone. Developed in Dayton, Ohio, this “aerial torpedo” (also called an “automatic carrier” or “flying bomb”) was created by automotive innovator Charles F. “Boss” Kettering and nicknamed, in his honor, the “Kettering Bug.” Along with Kettering, important future actors in American military airpower such as General of the Air Force Henry “Hap” Arnold and James Doolittle of “Doolittle’s Raiders” were also involved in this secret development project, probably the first of its kind in Air Force history. Like most projects pushing the limits of the state of the art, the Kettering Bug was hampered by technical challenges; however, the project showed how breakthroughs can be achieved when a small group of accomplished technical experts are brought together on a complex task and allowed to seek creative solutions. Theirs was no small accomplishment. Looking back on the project, General “Hap” Arnold’s assessment was: The Bug was twenty five years ahead of its time. -

Maritime Patrol Aviation: 90 Years of Continuing Innovation

J. F. KEANE AND C. A. EASTERLING Maritime Patrol Aviation: 90 Years of Continuing Innovation John F. Keane and CAPT C. Alan Easterling, USN Since its beginnings in 1912, maritime patrol aviation has recognized the importance of long-range, persistent, and armed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in sup- port of operations afl oat and ashore. Throughout its history, it has demonstrated the fl ex- ibility to respond to changing threats, environments, and missions. The need for increased range and payload to counter submarine and surface threats would dictate aircraft opera- tional requirements as early as 1917. As maritime patrol transitioned from fl ying boats to land-based aircraft, both its mission set and areas of operation expanded, requiring further developments to accommodate advanced sensor and weapons systems. Tomorrow’s squad- rons will possess capabilities far beyond the imaginations of the early pioneers, but the mis- sion will remain essentially the same—to quench the battle force commander’s increasing demand for over-the-horizon situational awareness. INTRODUCTION In 1942, Rear Admiral J. S. McCain, as Com- plane. With their normal and advance bases strategically mander, Aircraft Scouting Forces, U.S. Fleet, stated the located, surprise contacts between major forces can hardly following: occur. In addition to receiving contact reports on enemy forces in these vital areas the patrol planes, due to their great Information is without doubt the most important service endurance, can shadow and track these forces, keeping the required by a fl eet commander. Accurate, complete and up fl eet commander informed of their every movement.1 to the minute knowledge of the position, strength and move- ment of enemy forces is very diffi cult to obtain under war Although prescient, Rear Admiral McCain was hardly conditions. -

A GOULD ISLAND CHRONOLOGY and Some Associated Historical Notes by Captain Frank Snyder (USN Ret)

Occasional Paper # 3 A GOULD ISLAND CHRONOLOGY And Some Associated Historical Notes By Captain Frank Snyder (USN Ret) Gould Island, the small oblong island that lies off our eastern shore between Jamestown’s North End and Middletown, is an unexplored and, because of its dedicated uses, essentially unexplorable part of Jamestown. On August 9, 2003, during our Sunset History Cruise, Captain Frank Snyder, a retired Captain in the United States Navy and formerly a professor at the Naval War College, told us about the history of Gould Island, especially its use by the Navy. He provided the society with a detailed chronology of the island’s history. The following pages are excerpted from his talk and accompanying notes. Rosemary Enright A chain-link fence divides Gould Island into north March 28, 1657: Gould Island (then and south. The 17 acres north of the fence – Aquopimoquk) is sold to Thomas Gould, for whom administered by the U. S. Navy – is closed to the island is now named, by Scuttape, a grandson visitors. The area south of the fence – of Conanicus. The same year Conanicut Island is administered by the State of Rhode Island – is a purchased from the Indians by a group of bird sanctuary and is also closed to the public Newporters. except by special permit. May 20, 1673: Thomas Gould transfers one-half Statements of the island’s area vary from 40 acres of Gould Island to John Cranston, and then, a year (in the Providence Journal) to 56 acres (in early later, conveys the remaining half to Mr. -

Luftwaffe Maritime Operations in World War Ii

AU/ACSC/6456/2004-2005 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY LUFTWAFFE MARITIME OPERATIONS IN WORLD WAR II: THOUGHT, ORGANIZATION AND TECHNOLOGY by Winston A. Gould, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Instructor: Dr Richard R. Muller Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2005 Distribution A: Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited Ú±®³ ß°°®±ª»¼ λ°±®¬ ܱ½«³»²¬¿¬·±² п¹» ÑÓÞ Ò±ò ðéðìóðïèè Ы¾´·½ ®»°±®¬·²¹ ¾«®¼»² º±® ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·• »•¬·³¿¬»¼ ¬± ¿ª»®¿¹» ï ¸±«® °»® ®»•°±²•»ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ ¬¸» ¬·³» º±® ®»ª·»©·²¹ ·²•¬®«½¬·±²•ô •»¿®½¸·²¹ »¨·•¬·²¹ ¼¿¬¿ •±«®½»•ô ¹¿¬¸»®·²¹ ¿²¼ ³¿·²¬¿·²·²¹ ¬¸» ¼¿¬¿ ²»»¼»¼ô ¿²¼ ½±³°´»¬·²¹ ¿²¼ ®»ª·»©·²¹ ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ò Í»²¼ ½±³³»²¬• ®»¹¿®¼·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»² »•¬·³¿¬» ±® ¿²§ ±¬¸»® ¿•°»½¬ ±º ¬¸·• ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ •«¹¹»•¬·±²• º±® ®»¼«½·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»²ô ¬± É¿•¸·²¹¬±² Ø»¿¼¯«¿®¬»®• Í»®ª·½»•ô Ü·®»½¬±®¿¬» º±® ײº±®³¿¬·±² Ñ°»®¿¬·±²• ¿²¼ λ°±®¬•ô ïîïë Ö»ºº»®•±² Ü¿ª·• Ø·¹¸©¿§ô Í«·¬» ïîðìô ß®´·²¹¬±² Êß îîîðîóìíðîò λ•°±²¼»²¬• •¸±«´¼ ¾» ¿©¿®» ¬¸¿¬ ²±¬©·¬¸•¬¿²¼·²¹ ¿²§ ±¬¸»® °®±ª·•·±² ±º ´¿©ô ²± °»®•±² •¸¿´´ ¾» •«¾¶»½¬ ¬± ¿ °»²¿´¬§ º±® º¿·´·²¹ ¬± ½±³°´§ ©·¬¸ ¿ ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·º ·¬ ¼±»• ²±¬ ¼·•°´¿§ ¿ ½«®®»²¬´§ ª¿´·¼ ÑÓÞ ½±²¬®±´ ²«³¾»®ò ïò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÜßÌÛ íò ÜßÌÛÍ ÝÑÊÛÎÛÜ ßÐÎ îððë îò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÌÇÐÛ ððóððóîððë ¬± ððóððóîððë ìò Ì×ÌÔÛ ßÒÜ ÍËÞÌ×ÌÔÛ ë¿ò ÝÑÒÌÎßÝÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÔËÚÌÉßÚÚÛ ÓßÎ×Ì×ÓÛ ÑÐÛÎßÌ×ÑÒÍ ×Ò ÉÑÎÔÜ ÉßÎ ××æ ë¾ò ÙÎßÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÌØÑËÙØÌô ÑÎÙßÒ×ÆßÌ×ÑÒ ßÒÜ ÌÛÝØÒÑÔÑÙÇ ë½ò ÐÎÑÙÎßÓ ÛÔÛÓÛÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ -

Atlantic Fleet, It Is the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic On September 1, 1939 Germany invades Poland. Allies or go on the offensive with deadly submarine Two days later Britain and France declare war and wolf packs and surface raiders of the German the Battle of the Atlantic begins. Over the next five Kriegsmarine. years and eight months a deadly struggle would be fought on the high seas, from the frigid waters "The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating of the Arctic to the South Atlantic. factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening At the heart of the conflict was the tonnage war. elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended Britain required a continuous supply of imported ultimately on its outcome." - Winston Churchill war materials to keep on fighting and the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) was tasked with Getting Started preventing the arrival of these goods from across If this is your first time playing Atlantic Fleet, it is the Atlantic. recommended to begin by completing the Training Missions. To do so, simply select Training Missions Atlantic Fleet from the main menu. Atlantic Fleet is a turn-based tactical and strategic simulation of the Battle of the Atlantic. Take Continue with some Single Battles to get a feel for command of surface ships, submarines as well as combat and gunnery. The Battle of the River Plate carrier and land based aircraft in a deadly struggle and Convoy HX-106 battles (playing Germany for for control of shipping lanes during World War II. both) make for excellent initial practice. -

The British Torpedo Bombers Left Three Battleships Sunk Or Sinking in the Main Harbor of the Italian Battle Fleet

A painting hanging in Britain’s National Museum of the Royal Navy shows a torpedo plane from HMS Illustrious attacking the ships at Taranto harbor on Nov. 11, 1940. Painting by Charles David Cobb, The National Museum of the Royal Navy The British torpedo bombers left three battleships sunk or sinking in the main harbor of the Italian battle fleet. 60 MARCH 2017 H WWW.AIRFORCEMAG.COM of questions and interviewing as many eyewitnesses as they could. Taranto is often described as the precursor or blueprint for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 13 months later, but that is something of an exaggeration. Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto was already thinking about a strike on Pearl Harbor, possibly with aerial torpedoes. There is little doubt, though, that Taranto confirmed the feasibility of Yamamoto’s idea. Serious planning of By John T. Correll the attack and experiments to modify aerial torpedoes for use in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor—about the same depth as at Taranto—began in early 1941. CHALLENGE IN THE MED Adm. Andrew B. Cunningham, com- manding the British Mediterranean Fleet, was caught short-handed when Italian dictator Benito Mussolini de- clared war on Britain June 10, 1940. Some of Cunningham’s assets had been transferred to the Home Fleet for the impending Battle of Britain. Other British forces were tied down in North Africa, where an Italian army was massed on the frontier between Egypt and Libya. Cunningham had to keep the sea lanes open to the Suez Canal, the critical passage to India, Australia, and British possessions in Asia, but n the night of Nov. -

Nano Unmanned Aerial Vehicles - Drone Or Helicopter in Military S

Special Issue - 2019 International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 CONFCALL - 2019 Conference Proceedings Nano Unmanned Aerial Vehicles - Drone or Helicopter in Military S. Nagarajan Assistant Professor Dept of AERO- PITS Jagannathan Panneerselvam Raj Mohmed Sadiq Batcha Dept of AERO- PITS Dept of AERO- PITS Abstract:- An unmanned Aerial vehicle (UAV) (or un TERMINOLOGY: crewed aerial vehicle, commonly known as a Drone) Multiple terms are used for unmanned aerial vehicles, is an aircraft without a human pilot on board and a which generally refer to the same concept. The term drone, type of unmanned vehicle. The nano is a military more widely used by the public, was coined in reference to micro unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in use by the early remotely-flown target aircraft used for practice firing armed forces of the United States, France, the United of the battleships’ guns, and the term was first used with the Kingdom, Germany, Australia, Norway, the 1920s Fairey Queen and 1930s de Havilland Queen Bee Netherlands and India. The unit measures around target aircraft. The term unmanned aircraft system (UAS) 10*2.5 cm (4*1 in) and provides troops on the ground was adopted by the United States Department of Defense with local situational awareness. They are small (DoD) and the United States Federal Aviation enough to fit in one hand and weigh just over half an Administration in 2005 according to their Unmanned ounce (16 g, including batteries). The UAV is Aircraft System Roadmap 2005-2030. The International equipped with triple cameras(one looking forward, Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and British Civil one looking straight down, one pointing downward at Aviation Authority adopted this term, also used in the 45 degrees), which gives the operator full-motion European Union’s Single-European-Sky (SES) Air-Traffic- video and still images. -

Gallery of Classics

1 Air Force Magazine This is a recreation of an Air Force Magazine article. Photos February 1997 have been changed for online presentation. Some data has been updated for accuracy. GGaalllleerryy ooff CCllaassssiiccss Compiled by Jeffrey P. Rhodes Key FF First flight FFL First flight location FFM First flight model FFP First flight pilot USAF Air Force and all predecessors Models/variants Quantity production models and major variants Left: P-12 fighters FFL: Cleveland, Ohio. Bombers FFP: Unconfirmed. Models/variants: MB-2. NBS-1. MB-2/NBS-1 Powerplant: Two Packard Liberty 12A liquid-cooled V- A derivative of the first US-designed bomber, the Martin 12s of 420 hp each. MB-1, the MB-2 featured a number of improvements. Wingspan: 74 ft 2 in. Twenty MB-2s were ordered in June 1920, and the type Length: 42 ft 8 in. was rushed into production so that Brig. Gen. William L. Height: 15 ft 63/4 in. ―Billy‖ Mitchell could use the aircraft in the planned Weight: 13,695 lb gross. strategic bombing tests off the Virginia Capes. From July Armament: Five .30-cal. Lewis machine guns in nose 13–21, 1921, General Mitchell‘s 1st Provisional Air and amidships; 1,800 lb of bombs internally and up to Brigade, based at Langley Field, Va., sank three ships, 2,000 lb of bombs externally. including the captured German battleship Ostfriesland, Accommodation: Four (pilot, copilot/navigator, and demonstrated the vulnerability of naval vessels to bombardier/gunner, and rear gunner). aerial attack. The Air Service then ordered another 110 Cost: $17,490 (Curtiss). -

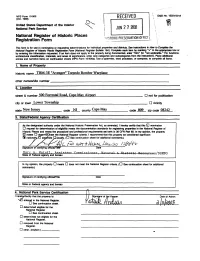

RECEIVED } OMB R^O

NPS Form 10-900 RECEIVED } OMB r^O. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN272002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ilSTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Pieces Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete ad Kerns. 1. Name of Property _____ historic name TBM-3E "Avenger" Torpedo Bomber Warplane_______________________ other names/site number 2. Location street & number 500 Forrestal Road, Cape May Airport D not for publication city or town Lower Township _ D vicinity New Jersey code_NJ_ county Cape May code 009 zip code 08242 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act. as amended, I hereby certify that this S nomination O request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets O doerrtoT^neet the National Register criteria. -

Video Preview

“The way I trained in the TBM [Avenger torpedo bomber] at Fort Lauderdale was to climb in and put the throttle forward and take off. There were no special simulators for the TBM.” — George H. W. Bush, Pilot, U.S. Navy, LTJG Table of Contents Click the section title to jump to it. Click any blue or purple head to return: Video Preview Video Voices Connect the Video to Science and Engineering Design Explore the Video Explore and Challenge Identify the Challenge Investigate, Compare, and Revise Pushing the Envelope Build Science Literacy through Reading and Writing Summary Activity Next Generation Science Standards Common Core State Standards for ELA & Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects Assessment Rubric For Inquiry Investigation Video Preview "The Torpedo Bomber" is one of 20 short videos in the series Chronicles of Courage: Stories of Wartime and Innovation. In October of 1944, during World War II, the United States Navy patrolled the dangerous Philippine island waters in the Pacific Ocean to support the Allied troops and intercept the Imperial Japanese Navy. They encountered one of the largest warships ever put to sea—the Japanese super-battleship Musashi. To carry out an attack, the U.S. relied on the Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger—a rugged 3-seat torpedo bomber with a powerful engine and a deadly 2,200-pound torpedo. Time Video Content 0:00–0:16 Series opening 0:17–1:11 Fighting the Japanese in the Pacific 1:12–1:37 The Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger Torpedo Bomber 1:38–2:35 Attacking a super-battleship 2:36–3:46 The torpedo as a weapon 3:47–4:20 Will Japan sink? 4:21–5:10 The end is in sight 5:11–5:25 Closing credits Chronicles of Courage: Stories of Wartime and Innovation “The Torpedo Bomber” 1 Video Voices—The Experts Tell the Story By interviewing people who have demonstrated courage in the face of extraordinary events, the Chronicles of Courage series keeps history alive for current generations to explore. -

Evolution of the Cruise Missile

The Evolution of the Cruise Missile by KENNETH P. WERRELL Air University (AU) Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Werrell, Kenneth P. The Evolution of the Cruise Missile . "September 1985 ." Includes bibliographies and index. 1 . Cruise Missiles-History . I. Air University (US) . II . Title. UG1312 .C7W47 1985 358'.174'0973 85-8131 First Printing 1985 Second Printing 1998 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the editors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents US Government Printing Office Washington DC 20402 90 t&iz c*nezieani a7lio ka(TE jzzvzJ, au jzviny, at wdl izzvE witfi tfiE ezuisz m.illiz. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK CONTENTS Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ii FOREWORD. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ix THE AUTHOR . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . .. .. .. .. ... .. xiii I INTRODUCTION . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Notes . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 II THE EARLY YEARS . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Foreign Efforts . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Navy-Sperry Flying Bomb . .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Army-Kettering Bug .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Foreign Developments . .. .. .. .. 17 The Army-Sperry Experiments . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 US