Lowland Deer Panel Report to Scottish Natural Heritage February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Falkirk Wheel, Scotland

Falkirk Wheel, Scotland Jing Meng Xi Jing Fang Natasha Soriano Kendra Hanagami Overview Magnitudes & Costs Project Use and Social and Economic Benefits Technical Issues and Innovations Social Problems and Policy Challenges Magnitudes Location: Central Scotland Purpose: To connecting the Forth and Clyde canal with the Union canal. To lift boats from a lower canal to an upper canal Magnitudes Construction Began: March 12, 1999 Officially at Blairdardie Road in Glasgow Construction Completed: May 24, 2002 Part of the Millennium Link Project undertaken by British Waterways in Scotland To link the West and East coasts of Scotland with fully navigable waterways for the first time in 35 years Magnitudes The world’s first and only rotating boat wheel Two sets of axe shaped arms Two diametrically opposed waterwater-- filled caissons Magnitudes Overall diameter is 35 meters Wheel can take 4 boats up and 4 boats down Can overcome the 24m vertical drop in 15 minute( 600 tones) To operate the wheel consumes just 1.5 kilowattkilowatt--hourshours in rotation Costs and Prices Total Cost of the Millennium Link Project: $123 M $46.4 M of fund came from Nation Lottery Falkirk Wheel Cost: $38.5 M Financing Project was funded by: British Waterways Millennium Commission Scottish Enterprise European Union Canalside local authorities Fares for Wheel The Falkirk Wheel Experience Tour: Adults $11.60 Children $6.20 Senior $9.75 Family $31.20 Social Benefits Proud Scots Queen of Scotland supported the Falkirk Wheel revived an important -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day

Holly Marriott Webb Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day Master’s thesis in Global Environmental History 1 Abstract Marriott Webb, H. 2019. Histories of Value: Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day. Uppsala, Department of Archaeology and Ancient His- tory. Imagining the English landscape as an assemblage entangling deer and people throughout history, this thesis explores how changes in deer population connect to the ways deer have been valued from 1800 to the present day. Its methods are mixed, its sources are conversations – human voices in the ongoing historical negotiations of the multispecies body politic, the moot of people, animals, plants and things which shapes and orders the landscape assemblage. These conversations include interviews with people whose lives revolve around deer, correspondence with the organisations that hold sway over deer lives, analysis of modern media discourse around deer issues and exchanges with the history books. It finds that a non-linear increase in deer population over the time period has been accompanied by multiple changes in the way deer are valued as part of the English landscape. Ending with a reflection on how this history of value fits in to wider debates about the proper representation of animals, the nature of non-human agency, and trajectories of the Anthropocene, this thesis seeks to open up new ways of exploring questions about human- animal relationships in environmental history. Keywords: Assemblages, Deer, Deer population, England, Hunting, Landscape, Making killable, Moots, Multispecies, Nativist paradigm, Olwig, Pests, Place, Trash Animals, Tsing, United Kingdom, Wildlife management. -

Police Division.Dot

Safer Communities Directorate Police Powers Unit T: 0131-244-2355 E: [email protected] T Johnson Via email ___ Our ref: FOI/13/00538 26 April 2013 Dear T Johnson Thank you for your email dated 5 April, in which you make a request under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 (FOISA) for: 1) Information about the make, model and muzzle energy of the gun used in the fatal shooting of a child in Easterhouse in 2005; 2) Details of the number of meetings, those involved in said meetings and the minutes of meetings regarding the Scottish Firearms Consultative Panel (SFCP); 3) Information regarding land that provides a safe shooting ground that is as accessible as a member of the public’s own garden, or clubs that offer open access to the general public; and 4) Details of any ranges that people can freely rent similar to other countries, in the central belt area of Scotland. In relation to your request number 1), I have assumed that you are referring specifically to the death of Andrew Morton. Following a search of our paper and electronic records, I have established that the information you have requested is not held by the Scottish Government. You may wish to contact either the police or Procurator Fiscal Service, who may be able to provide this information. Contact details for Police Scotland can be found online at www.scotland.police.uk/access-to-information/freedom-of-information/, and for the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service at www.crownoffice.gov.uk/FOI/Freedom-Information- and-Environmental-Information-Regulations. -

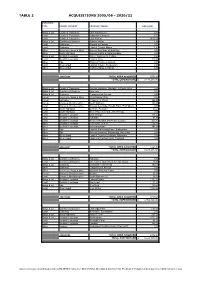

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Scottish Register of Tartans Bill (SP Bill 76 ) As Introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 27 September 2006

This document relates to the Scottish Register of Tartans Bill (SP Bill 76 ) as introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 27 September 2006 SCOTTISH REGISTER OF TARTANS BILL —————————— POLICY MEMORANDUM INTRODUCTION 1. This document relates to the Scottish Register of Tartans Bill introduced in the S cottish Parliament on 27 September 2006 . It has been prepared by Jamie McGrigor MSP, the member in charge of the Bill with the assistance of the Parliament’s Non Executive Bills Unit to satisfy Rul e 9.3.3(c ) of the Parliament ’s Standing Orders. The contents are entirely the responsibility of the member and have not been endorsed by the Parliament. Explanatory Notes and other accompanying documents are published separately as SP Bill 76 –EN. POLICY OBJECTIVES OF THE BILL Overview 2. The Bill provides for the establishment of a Register of Tartans and for the appointment of a Keeper to administer and maintain the Register . 3. The stated purpose of the Bill is to create an archive of tartans for reference and information purposes. It is also hoped that the existence of the Register will help promote tartan generally by providing a central point of focus for those interested in tartan . Key objective of the Bill 4. The object ive of the Bill is to create a not for profit Scottish Registe r. While registration is voluntary the Register will function as both a current record and a national archive and will be accessible to the public. Registration does not interfere with existing rights in tartan or create any additional rights and the purpose of registration is purely to create, over time, a central, authoritative source of information on tartan designs. -

O'er Crag and Torrent with Rod and Gun : Shooting and Fishing

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ', \r . O'ER CRAG AND TORRENT 4 O'ER CRAG AND TORRENT 6un SHOOTING AND FISHING BY W. STANHOPE-LOVELL LONDON R. A. EVERETT & CO. 42 ESSEX STREET, STRAND, W.C. 1904 All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS fAGE DEDICATION 7 PREFACE - n OTTER HUNTING 13 FOOT HARRIERS 45 PSEUDONYMOUS FOOT BEAGLES - - - - 57 BADGERS ------.-. 7! GROUSE SHOOTING IN - - IRELAND OVER DOGS .105 ST. GILES' DAY II9 ON THE BORDERS OF DARTMOOR WITH THE PARTRIDGES 129 PHEASANT - SHOOTING I 4I SNIPE SHOOTING IN IRELAND 153 TROUT FISHING IN WICKLOW 165 " A RED LETTER - DAY ON THE CAMEL RIVER" 191 SEA FISHING AT ST. IVES 20$ SHEEP-DOG TRIALS 215 A SPORTSMAN'S CHRISTMAS .... 227 MY DERBY SWEEP ----... 239 ODDS AND ENDS 249 EXODUS 257 ' JOHN A. DOYLE, ESQ., J.P.D.L. AND FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE, OXFORD THESE UNPRETENTIOUS EFFORTS ARE DEDICATED WITH EVERY SENTIMENT OF REGARD AND AS A SMALL TOKEN OF APPRECIATION OF THE MANY HAPPY DAYS OF SPORT I AND MINE HAVE SPENT THROUGH HIS INSTRUMENTALITY AND KINDNESS. WM. STANHOPE-LOVELL (Fiery Brown), Pendarren Cottage, July, 1904. PREFACE SOME of the reminiscences recorded in the following pages were originally written for Land and Water to whose editor I am indebted for unvarying courtesy and kindness and for other papers. The idea of publishing some of my recol- lections in book form was suggested in the smoking-room, after a very pleasant shoot, by some keen old friends, well known in the world of sport, who urged me to write a series of short anecdotes relating to various forms of our common pleasure, based on personal and practical experience. -

Game Bird Farm and Shooting Preserve Programs

Game Bird Farm and Shooting Preserve Programmatic EIS 3 - 1 Game Bird Farm and Shooting Preserve Programs FINAL PROGRAMMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT December 2001 Final PEIS Game Bird Farm and Shooting Preserve Programmatic EIS 3 - 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1-1 BACKGROUND FOR PROGRAMMATIC EIS ...................................................................................1-1 PURPOSE AND NEED .......................................................................................................................1-2 ROLE OF FWP AND OTHER GOVERNMENT AGENCIES.............................................................1-2 PUBLIC SCOPING..............................................................................................................................1-3 Issues Raised During Scoping Period...................................................................................1-3 Wildlife ......................................................................................................................1-3 Vegetation.................................................................................................................1-3 Noise.........................................................................................................................1-3 Socioeconomic .........................................................................................................1-3 PUBLIC COMMENTS -

"I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speth, Alana, ""I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624392. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-szar-c234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth Nicholson, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alana Speth Approved by the Committee L Committee Chair Pullen Professor James Whittenburg, History The College of William and Mary Professor LuAnn Homza, History The College of William and Mary • 7 i ^ i Assistant Professor Kathrin Levitan, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE The radical and complex changes that unfolded in the Scottish Highlands beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century have often been depicted as an example of mainstream British assimilation. -

Scottish Lowlands FD Strategic Plan 2007-2017

SCOTTISH LOWLANDS FOREST DISTRICT STRATEGIC PLAN 2007 – 2017 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 1 Contents 1 Planning framework 3 2 Description of the District 8 3 Evaluation of the previous District Strategic Plan 15 4 Identification and analysis of issues 16 5 Response to the issues, implementation and monitoring 30 Appendices 1 Evaluation of achievements (1999-2006) under previous Strategic Plan 49 2 List of local plans and guidance 61 3 Scheduled ancient monuments, sites of special scientific interest and ancient woodland sites 63 4 District map 5 Standard maps 67-77 6 Key issues cross-referenced to SFS themes 78 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 2 1 Planning framework 1.1 Introduction Forestry in Scotland is the responsibility of Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Government. Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) acts as the Scottish Government’s Forestry Department. Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES) is an executive agency of FCS with the role of managing the national forest estate according to FCS policies. Scottish Lowlands Forest District is the part of FES with responsibility for management of the estate in central Scotland. The aim of this Plan is to describe how the District will deliver its part of the Scottish Forestry Strategy (SFS 2006), which is the forest policy of the Scottish Government. The strategy articulates a vision for forestry in Scotland, to be met by 2025. Scottish Forestry Strategy Vision By the second half of this century, people are benefiting widely from Scotland's trees, woodlands and forests, actively engaging with and looking after them for the use and enjoyment of generations to come. -

Deer Legislation

Introduction This guide describes the general principles of the law relating to wild deer, it is not a full description of It is therefore advisable to carry written permission that law. It is important to study the full legislation as proof of your right to be on the land. to which this guide relates (see Further Information) Practitioners need to be fully conversant with current Exemptions. An offence is not committed if the legislation in order to make informed management perpetrator did so in the belief that he would have decisions and be sure that their actions are legal. been given consent if the owner or occupier knew of his doing it and the circumstances, or he has other The following defi nitions apply: lawful authority. “Deer” means deer of any species and includes the Ownership of deer. Deer which can roam carcass or any part thereof freely are wild animals and are not owned by, or “Night” means the period between 1 hour after the responsibility of, anyone. A wild deer becomes sunset and 1 hour before sunrise the property of the landowner when “reduced into “Vehicle” includes any vehicle including aircraft, possession” i.e. killed or captured, thus a culled deer hovercraft or boat is the property of the owner of the land on which it dies, a deer killed in a road accident is the property The law specifi cally relating to deer in England and of the owner of the highway, verge or land on which Wales is contained in the Deer Act 1991(Deer Act) it falls.