Advancing a Clinically Relevant Perspective of the Clonal Nature of Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Profiling Data

Compound Name DiscoveRx Gene Symbol Entrez Gene Percent Compound Symbol Control Concentration (nM) JNK-IN-8 AAK1 AAK1 69 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(E255K)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 87 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 65 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-phosphorylated ABL1 61 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 42 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-phosphorylated ABL1 60 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(M351T)-phosphorylated ABL1 81 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-phosphorylated ABL1 56 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-phosphorylated ABL1 92 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Y253F)-phosphorylated ABL1 71 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-nonphosphorylated ABL1 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL2 ABL2 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1 ACVR1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1B ACVR1B 88 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2A ACVR2A 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2B ACVR2B 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVRL1 ACVRL1 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK3 CABC1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK4 ADCK4 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT1 AKT1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT2 AKT2 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT3 AKT3 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ALK ALK 85 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha1 PRKAA1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha2 PRKAA2 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 ANKK1 ANKK1 75 1000 JNK-IN-8 ARK5 NUAK1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK1 MAP3K5 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK2 MAP3K6 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 83 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKC AURKC 95 1000 JNK-IN-8 -

Supplementary Table 1

SI Table S1. Broad protein kinase selectivity for PF-2771. Kinase, PF-2771 % Inhibition at 10 μM Service Kinase, PF-2771 % Inhibition at 1 μM Service rat RPS6KA1 (RSK1) 39 Dundee AURKA (AURA) 24 Invitrogen IKBKB (IKKb) 26 Dundee CDK2 /CyclinA 21 Invitrogen mouse LCK 25 Dundee rabbit MAP2K1 (MEK1) 19 Dundee AKT1 (AKT) 21 Dundee IKBKB (IKKb) 16 Dundee CAMK1 (CaMK1a) 19 Dundee PKN2 (PRK2) 14 Dundee RPS6KA5 (MSK1) 18 Dundee MAPKAPK5 14 Dundee PRKD1 (PKD1) 13 Dundee PIM3 12 Dundee MKNK2 (MNK2) 12 Dundee PRKD1 (PKD1) 12 Dundee MARK3 10 Dundee NTRK1 (TRKA) 12 Invitrogen SRPK1 9 Dundee MAPK12 (p38g) 11 Dundee MAPKAPK5 9 Dundee MAPK8 (JNK1a) 11 Dundee MAPK13 (p38d) 8 Dundee rat PRKAA2 (AMPKa2) 11 Dundee AURKB (AURB) 5 Dundee NEK2 11 Invitrogen CSK 5 Dundee CHEK2 (CHK2) 11 Invitrogen EEF2K (EEF-2 kinase) 4 Dundee MAPK9 (JNK2) 9 Dundee PRKCA (PKCa) 4 Dundee rat RPS6KA1 (RSK1) 8 Dundee rat PRKAA2 (AMPKa2) 4 Dundee DYRK2 7 Dundee rat CSNK1D (CKId) 3 Dundee AKT1 (AKT) 7 Dundee LYN 3 BioPrint PIM2 7 Invitrogen CSNK2A1 (CKIIa) 3 Dundee MAPK15 (ERK7) 6 Dundee CAMKK2 (CAMKKB) 1 Dundee mouse LCK 5 Dundee PIM3 1 Dundee PDPK1 (PDK1) (directed 5 Invitrogen rat DYRK1A (MNB) 1 Dundee RPS6KB1 (p70S6K) 5 Dundee PBK 0 Dundee CSNK2A1 (CKIIa) 4 Dundee PIM1 -1 Dundee CAMKK2 (CAMKKB) 4 Dundee DYRK2 -2 Dundee SRC 4 Invitrogen MAPK12 (p38g) -2 Dundee MYLK2 (MLCK_sk) 3 Invitrogen NEK6 -3 Dundee MKNK2 (MNK2) 2 Dundee RPS6KB1 (p70S6K) -3 Dundee SRPK1 2 Dundee AKT2 -3 Dundee MKNK1 (MNK1) 2 Dundee RPS6KA3 (RSK2) -3 Dundee CHEK1 (CHK1) 2 Invitrogen rabbit MAP2K1 (MEK1) -4 Dundee -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Anti-MAP3K10 Product Datasheet

Anti-MAP3K10 Product Datasheet Polyclonal Antibody PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Product Name Anti-MAP3K10 Product Number HPA007039 Gene Description mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 10 Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Host Rabbit Antigen Sequence Recombinant Protein Epitope Signature Tag (PrEST) antigen sequence: LPSGFEHKITVQASPTLDKRKGSDGASPPASPSIIPRLRAIRLTPVDCGG SSSGSSSGGSGTWSRGGPPKKEELVGGKKKGRTWGPSSTLQKERVGGEER LKGLGEGSKQWSSS Purification Method Affinity purified using the PrEST antigen as affinity ligand Verified Species Human Reactivity Recommended IHC (Immunohistochemistry) Applications - Antibody dilution: 1:200 - 1:500 - Retrieval method: HIER pH6 ICC-IF (Immunofluorescence) - Fixation/Permeabilization: PFA/Triton X-100 - Working concentration: 0.25-2 µg/ml Characterization Data Available at atlasantibodies.com/products/HPA007039 Buffer 40% glycerol and PBS (pH 7.2). 0.02% sodium azide is added as preservative. Concentration Lot dependent Storage Store at +4°C for short term storage. Long time storage is recommended at -20°C. Notes Gently mix before use. Optimal concentrations and conditions for each application should be determined by the user. For protocols, additional product information, such as images and references, see atlasantibodies.com. Product of Sweden. For research use only. Not intended for pharmaceutical development, diagnostic, therapeutic or any in vivo use. No products from Atlas Antibodies may be resold, modified for resale or used to manufacture commercial products without prior written approval from Atlas Antibodies AB. Warranty: The products supplied by Atlas Antibodies are warranted to meet stated product specifications and to conform to label descriptions when used and stored properly. Unless otherwise stated, this warranty is limited to one year from date of sales for products used, handled and stored according to Atlas Antibodies AB's instructions. Atlas Antibodies AB's sole liability is limited to replacement of the product or refund of the purchase price. -

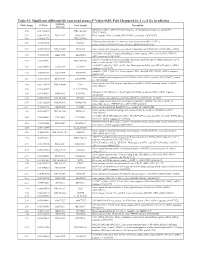

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Comprehensive Analyses of DNA Repair Pathways, Smoking and Bladder Cancer Risk in Los Angeles and Shanghai

IJC International Journal of Cancer Comprehensive analyses of DNA repair pathways, smoking and bladder cancer risk in Los Angeles and Shanghai Roman Corral1,2, Juan Pablo Lewinger1,2, David Van Den Berg1,2, Amit D. Joshi3, Jian-Min Yuan4, Manuela Gago-Dominguez1,2,5, Victoria K. Cortessis1,2,6, Malcolm C. Pike1,2,7, David V. Conti1,2, Duncan C. Thomas1,2, Christopher K. Edlund2, Yu-Tang Gao8, Yong-Bing Xiang8, Wei Zhang8, Yu-Chen Su1,2 and Mariana C. Stern1,2 1 Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine of USC, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 2 Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 3 Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA 4 Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, University of Pittsbugh, Pittsburgh, PA 5 Galician Foundation of Genomic Medicine, Complexo Hospitalario Universitario Santiago, Servicio Galego de Saude, IDIS, Santiago de Compostela, Spain 6 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 7 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 8 Department of Epidemiology, Shanghai Cancer Institute and Cancer Institute of Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China Tobacco smoking is a bladder cancer risk factor and a source of carcinogens that induce DNA damage to urothelial cells. Using data and samples from 988 cases and 1,004 controls enrolled in the Los Angeles County Bladder Cancer Study and the Shanghai Bladder Cancer Study, we investigated associations between bladder cancer risk and 632 tagSNPs that comprehensively capture genetic variation in 28 DNA repair genes from four DNA repair pathways: base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination repair (HHR). -

Supplemental Material 1

Cdk20 Csrp2bp Bub1 Tmed3 1700012B15Rik Uck1 Atad2 Pbk Rfc4 Ucp3 Mtmr7 Bid Rad9 Hadh Zc3h12a Bcl2l11 1700052K11Rik Cd83 Ncaph Cdca7l Ezh2 Kif23 Rel Cdh13 Nr4a1 Pola1 Phf19 Vldlr Snx7 Fam96a Ripk2 Ccne2 Ncapd2 Pqlc3 A130009I22Rik Niacr1 Peli1 Cenpn Ralgds Dbf4 Trpc6 Gadd45b Dyrk2 Il1b Prim1 Pcna Dnmt1 Ttc30a1 Cflar Fas Tro Tank Rapgef2 Icosl 9930012K11Rik Cd28 Ccdc86 Ube2f Klhl6 Commd8 Ccrl2 D4Wsu53e Tnfaip8l2 Ehd1 Kdm2b Uhrf1 Trim37 Tecrl AI467606 Ilf2 Cobra1 Aurkb Cdc42ep2 Nfkbil2 Appbp2 Nfkbiz Zfp85-rs1 Nlrp3 Zmym5 Il6 Foxo3 Sept3 Ets2 Serpinb2 Smc3 Msh6 Itga5 Gpsm3 Slbp Dennd4c Rffl Trappc1 Mrpl34 Socs3 Ocel1 Tnfaip3 Swap70 1110003O08Rik Junb Pmm1 Cxcl10 Brca1 Acpl2 Coq10b Marcksl1 Map3k10 Braf Tnf Icam1 Pold3 AI462493 Nfkbia Dnmbp Dnajc9 Tnip1 Chfr Trim13 Slc35c2 Rb1 C78513 Limk1 C1qa Fen1 BC088983 Tsc22d3 Tnfsf9 Mapk3 E2f1 Zc3h12c Casp4 Ttf2 Maff Gmnn Zfp715 Mdm2 Mcm7 Irf1 Parp1 Ftsj2 Myo10 Irak2 Mid1ip1 Apeh Rad51c Map3k4 Tk1 E2f7 Tiparp Ptgs2 Spata13 Hmga2-ps1 Wdhd1 Clspn Ubac1 Erp29 Thap4 Dna2 Prkag2 Il1a Rfwd3 Gbp3 Cdca5 3110043O21Rik Clec4e Cxcl11 Speg Tarbp2 Cdk2 Zufsp Cdca2 E2f2 1700054N08Rik Tnfsf10 5730499H23Rik Inf2 C1qb Anapc5 Sco1 Bst2 2010107G23Rik Cnpy4 D10Wsu102e Brip1 H2-D1 Gpd1l Suv420h2 4930579G24Rik Cdc6 Cntnap2 Cyp2b10 Plod2 Irf7 C2 Lsm3 9330175E14Rik Aak1 Ick Rassf7 Cd22 Cd72 Tap1 Tcn2 Malt1 Uba7 Atp1a2 Ar Tap2 Cd86 Herc5 Heca Atp2a2 Ttc28 Dhrs3 Stat1 Ccdc22 Abca5 Nhlrc2 Ddx58 Gpx1 Dgkd Fbxl7 Lap3 Lama4 Neil1 Enpp4 Tpst1 Cybb Ccne1 Sec24d Fcgr4 Hk3 Rasgrp2 Dcun1d2 Vegfa Ecsit Ddx60 Eif2ak2 Cyp2r1 Gimap4 Fip1l1 -

Role and Regulation of the P53-Homolog P73 in the Transformation of Normal Human Fibroblasts

Role and regulation of the p53-homolog p73 in the transformation of normal human fibroblasts Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Lars Hofmann aus Aschaffenburg Würzburg 2007 Eingereicht am Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Dr. Martin J. Müller Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael P. Schön Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Georg Krohne Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig angefertigt und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel und Quellen verwendet habe. Diese Arbeit wurde weder in gleicher noch in ähnlicher Form in einem anderen Prüfungsverfahren vorgelegt. Ich habe früher, außer den mit dem Zulassungsgesuch urkundlichen Graden, keine weiteren akademischen Grade erworben und zu erwerben gesucht. Würzburg, Lars Hofmann Content SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ IV ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ............................................................................................. V 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Molecular basics of cancer .......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Early research on tumorigenesis ................................................................................. 3 1.3. Developing -

Title Human Genetic Diversity Possibly Determines Human's Compliance to COVID-19

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 April 2020 Title Human genetic diversity possibly determines human's compliance to COVID-19 1* 2 1 1 1 1 2 2 Yiqiang Zhao , Yongji Liu , Sa Li , Yuzhan Wang , Lina Bu , Qi Liu , Hongyi Lv , Fang Wan , Lida Wu2, Zeming Ning3, Yuchun Gu2,4* 1. Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China 2. Allife Medicine Ltd., Beijing, China 3. The Wellcome Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Cambridge, UK 4. Regenerative Medicine Center, Aston University, Birmingham, UK Corresponding Author Prof. Yiqiang Zhao Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health China Agricultural University Beijing, China Email: [email protected] And Prof. Yuchun Gu The regenerative Medicine Center Aston University Birmingham, UK & Allife Medicine Co.Ltd Beijing, China Email: [email protected] © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 April 2020 Abstract The rapid spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a serious threat to public health systems globally and is subsequently, a cause of anxiety and panic within human society. Understanding the mechanisms and reducing the chances of having severe symptoms from COVID-19 will play an essential role in treating the disease, and become an urgent task to calm the panic. However, the COVID-19 test developed to identify virus carriers is unable to predict symptom development in individuals upon infection. Experiences from other plagues in human history and COVID-19 statistics suggest that genetic factors may determine the compliance with the virus, i.e., severe, mild, and asymptomatic. -

Supplementary Materials and Tables a and B

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1 Table A. Main characteristics of the subset of 23 AML patients studied by high-density arrays (subset A) WBC BM blasts MYST3- MLL Age/Gender WHO / FAB subtype Karyotype FLT3-ITD NPM status (x109/L) (%) CREBBP status 1 51 / F M4 NA 21 78 + - G A 2 28 / M M4 t(8;16)(p11;p13) 8 92 + - G G 3 53 / F M4 t(8;16)(p11;p13) 27 96 + NA G NA 4 24 / M PML-RARα / M3 t(15;17) 5 90 - - G G 5 52 / M PML-RARα / M3 t(15;17) 1.5 75 - - G G 6 31 / F PML-RARα / M3 t(15;17) 3.2 89 - - G G 7 23 / M RUNX1-RUNX1T1 / M2 t(8;21) 38 34 - + ND G 8 52 / M RUNX1-RUNX1T1 / M2 t(8;21) 8 68 - - ND G 9 40 / M RUNX1-RUNX1T1 / M2 t(8;21) 5.1 54 - - ND G 10 63 / M CBFβ-MYH11 / M4 inv(16) 297 80 - - ND G 11 63 / M CBFβ-MYH11 / M4 inv(16) 7 74 - - ND G 12 59 / M CBFβ-MYH11 / M0 t(16;16) 108 94 - - ND G 13 41 / F MLLT3-MLL / M5 t(9;11) 51 90 - + G R 14 38 / F M5 46, XX 36 79 - + G G 15 76 / M M4 46 XY, der(10) 21 90 - - G NA 16 59 / M M4 NA 29 59 - - M G 17 26 / M M5 46, XY 295 92 - + G G 18 62 / F M5 NA 67 88 - + M A 19 47 / F M5 del(11q23) 17 78 - + M G 20 50 / F M5 46, XX 61 59 - + M G 21 28 / F M5 46, XX 132 90 - + G G 22 30 / F AML-MD / M5 46, XX 6 79 - + M G 23 64 / M AML-MD / M1 46, XY 17 83 - + M G WBC: white blood cell. -

Computational Inferences of Mutations Driving Mesenchymal Differentiation in Glioblastoma

Computational Inferences of Mutations Driving Mesenchymal Differentiation in Glioblastoma James Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 ! 2013 James Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Computational Inferences of Mutations Driving Mesenchymal Differentiation in Glioblastoma James Chen This dissertation reviews the development and implementation of integrative, systems biology methods designed to parse driver mutations from high- throughput array data derived from human patients. The analysis of vast amounts of genomic and genetic data in the context of complex human genetic diseases such as Glioblastoma is a daunting task. Mutations exist by the hundreds, if not thousands, and only an unknown handful will contribute to the disease in a significant way. The goal of this project was to develop novel computational methods to identify candidate mutations from these data that drive the molecular differentiation of glioblastoma into the mesenchymal subtype, the most aggressive, poorest-prognosis tumors associated with glioblastoma. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1… Introduction and Background 1 Glioblastoma and the Mesenchymal Subtype 3 Systems Biology and Master Regulators 9 Thesis Project: Genetics and Genomics 20 CHAPTER 2… TCGA Data Processing 23 CHAPTER 3… DIGGIn Part 1 – Selecting f-CNVs 33 Mutual Information 40 Application and Analysis 45 CHAPTER 4… DIGGIn Part 2 – Selecting drivers 52 CHAPTER 5… KLHL9 Manuscript 63 Methods 90 CHAPTER 5a… Revisions work-in-progress 105 CHAPTER 6… Discussion 109 APPENDICES… 132 APPEND01 – TCGA classifications 133 APPEND02 – GBM f-CNV list 136 APPEND03 – MES f-CNV candidate drivers 152 APPEND04 – Scripts 149 APPEND05 – Manuscript Figures and Legends 175 APPEND06 – Manuscript Supplemental Materials 185 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Califano Lab and my mentor, Andrea Califano, for their intellectual and motivational support during my stay in their lab.