Affinity-Seeking in the Classroom: Which Strategies Are Associated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

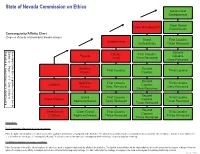

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Criminal Code

2010 Colección: Traducciones del derecho español Edita: Ministerio de Justicia - Secretaría General Técnica NIPO: 051-13-031-1 Traducción jurada realizada por: Clinter Actualización realizada por: Linguaserve Maquetación: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones ORGANIC ACT 10/1995, DATED 23RD NOVEMBER, ON THE CRIMINAL CODE. GOVERNMENT OFFICES Publication: Official State Gazette number 281 on 24th November 1995 RECITAL OF MOTIVES If the legal order has been defined as a set of rules that regulate the use of force, one may easily understand the importance of the Criminal Code in any civilised society. The Criminal Code defines criminal and misdemeanours that constitute the cases for application of the supreme action that may be taken by the coercive power of the State, that is, criminal sentencing. Thus, the Criminal Code holds a key place in the Law as a whole, to the extent that, not without reason, it has been considered a sort of “Negative Constitution”. The Criminal Code must protect the basic values and principles of our social coexistence. When those values and principles change, it must also change. However, in our country, in spite of profound changes in the social, economic and political orders, the current text dates, as far as its basic core is concerned, from the last century. The need for it to be reformed is thus undeniable. Based on the different attempts at reform carried out since the establishment of democracy, the Government has prepared a bill submitted for discussion and approval by the both Chambers. Thus, it must explain, even though briefly, the criteria on which it is based, even though these may easily be deduced from reading its text. -

Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers Working Papers 2004 Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ public_law_and_legal_theory Part of the Law Commons Chicago Unbound includes both works in progress and final versions of articles. Please be aware that a more recent version of this article may be available on Chicago Unbound, SSRN or elsewhere. Recommended Citation Elizabeth Emens, "Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence" (University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper No. 58, 2004). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO PUBLIC LAW AND LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 58 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE Elizabeth F. Emens THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO February 2003 This paper can be downloaded without charge at http://www.law.uchicago.edu/academics/publiclaw/index.html and at The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=506242 1 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE 29 N.Y.U. REVIEW OF LAW & SOCIAL CHANGE (forthcoming 2004) Elizabeth F. Emens† Work-in-progress: Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission. I. INTRODUCTION II. COMPULSORY MONOGAMY A. MONOGAMY’S MANDATE 1. THE WESTERN ROMANCE TRADITION 2. -

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange Edited by Thomas Schweizer University of Cologne Douglas R. White University of California, Irvine CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WEALTH TRANSFERS OCCASIONED BY MARRIAGE: A COMPARATIVE RECONSIDERATION Duran Bell INTRODUCTION The theory of marriage payments has been oriented toward explaining why various categories of practice take place under particular ecological and technological conditions (Bossen 1988; Goody 1973; Spiro 1975; Harrel and Dickey 1985; Kressel 1977; Schlegel and Eloul 1988; Tambiah 1989; and others). This effort has been productive of a wide range of important analytical findings. However, the results of this chapter suggest that some of that work should be reconsidered by reference to a more systematic and scientifically established set of analytical categories. The attempt here is to observe wealth transfers associated with marriage in all forms of society and to reexamine those transfers on the basis of a set of theoretical understandings that have, heretofore, remained only inchoate in theliterature. The principal theoretical issue is the importance of identifying individuals as incumbents of person- categories within socially constructed collectivities. The prevailing analytical perspective tends to present reciprocity as the elementary unit of social action, as is well illustrated by the influential work of Sahlins (1972), and it presents the individual as the elementary social actor. This perspective is related to a view of human action that has deep roots in post-Enlightenment thought, but it constitutes, I believe, a serious disability for the advancement of our understanding of a broad range of social processes. The presentation here makes no attempt to construct a case against the individualist-reciprocity paradigm. -

Attachment Orientations and Relationship Maintenance in College Friendships Samuel Chung Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-2018 Attachment Orientations and Relationship Maintenance in College Friendships Samuel Chung Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Personality and Social Contexts Commons Recommended Citation Chung, Samuel, "Attachment Orientations and Relationship Maintenance in College Friendships" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1280. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1280 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences Attachment Orientations and Relationship Maintenance in College Friendships by Samuel Chung A thesis presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, Samuel Chung Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. -

Cultural Differences in Adult Attachment and Facial Emotion Recognition

University of Ulm Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy Director: Prof. Dr. Harald Gündel Section Medical Psychology Head: Prof. Dr. Harald C. Traue Cultural Differences in Adult Attachment and Facial Emotion Recognition Dissertation to obtain the Doctoral Degree of Human Biology (Dr. biol. hum.) at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ulm by Hang Li born in Huolinguole, Inner Mongolia, P.R. China 2013 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Dr. Thomas Wirth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Harald C. Traue 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. phil. Ute Ziegenhain Tag der Promotion: 18. 10. 2013 CONTENTS Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................................... I Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... III 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Issues ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Attachment and facial emotion recognition .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Individualism and collectivism ............................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Cultural differences -

Taken Before. for the Bride. 56

THE GIFT OF THE BRIDE: A CRITICAL NOTE ON MAURICE FREEDMAN'S INTERPRETATION OF TRADITIONAL CHINESE MARRIAGE John McCreery Freedman (1970:185) has asserted that the patrilocal grand form of marriage in traditional Chinese society would leave the family of the bride ritually and socially inferior to the family of the groom. He says, The rites of marriage demonstrate that the bride's body, fertility, domestic service and loyalty are handed over by one family to another. To her natal family the loss is severe, both emotionally and economically: a member of the family is turned into a drain on its resources and a potential foe (Freedman, 1970:185). In making these assertions Freedman reiterated a position he had taken before. There is a Chinese proverb which says, "A boy is born facing in; a girl is born facing out." In other words from the moment she comes into life a girl is a potential loss to her family. Among Singapore Chinese from southern Fukien daughters are spoken of as "goods on which one loses." These statements re- flect the rule that a woman left her family on marriage and contributed children to the group into which she married. Her domestic services, her fertility, and her chief ritual attach- ments were transferred from one family to another. The con- veyance of rights in a woman from one family to another was validated by the passage of bride-price (Freedman, 1958:31). It is fair, I think, to say that for Freedman the rites of the patri- local grand form of marriage were first and foremost a rite de passage for the bride. -

April 2018 1. Current Leave and Other Employment-Related Policies To

Spain1 Gerardo Meil (Autonomous University of Madrid), Irene Lapuerta (Public University of Navarre) and Anna Escobedo (University of Barcelona) April 2018 For comparisons with other countries in this review on leave provision and early childhood education and care services, please see the cross-country tables at the front of the review (also available individually on the Leave Network website). To contact authors of country notes, see the members page on the Leave Network website. 1. Current leave and other employment-related policies to support parents a. Maternity leave (Permiso y prestación por maternidad) (responsibility of the Ministry of Labour and Social Security) Length of leave (before and after birth) • Sixteen (16) weeks: six weeks are obligatory and must be taken following the birth, while the remaining ten weeks can be taken before or after birth. Payment and funding • One hundred (100) per cent of earnings up to a ceiling of €3,751.20 a month in 2017 and 2018. • A flat-rate benefit (€537.84 per month or €17.84 per day) is paid for 42 calendar days to all employed women who do not meet eligibility requirements (a mere increase of 18 cents per day since July 2016, after being unchanged since 2010). • Financed by social insurance contributions from employers and employees. As a rule, employers pay 23.6 per cent of gross earnings and employees pay 4.7 per cent to cover common contingencies which include pensions, sickness and leaves (contingencias comunes), with an additional contribution paid to cover unemployment. In the case of public servants, all contributions are paid by their employer. -

Wedding Planning Checklist

Wedding Planning Checklist From booking your venue to creating your registry of gifts, you’ll have plenty of wedding-related tasks to handle. Here is a sample wedding checklist that covers the major items, along with a suggested timeline. Remember to have fun and take time along the way to relax and recharge. You’ve got a big day — and a bright future — ahead! 16-9 Months Out 4-5 Months Out 2 Months Out Start looking through magazines and Book the rehearsal venue. Touch base with all vendors. on websites such as Pinterest for Attend tastings, choose your baker and Meet with your photographer and inspiration. Put all your ideas in one order your cake. videographer. place, or start your own wedding board. Send your guest list to your shower host. Review the playlist with your DJ or Determine your budget. Figure out band. how much you can spend based on all Order your veil, shoes and other contributions. accessories. Enjoy your shower(s) and your bachelorette party. Choose your wedding party and ask Schedule your first dress fitting. them to participate. Try out makeup and hair artists; book Start your preliminary guest list. your favorite. 1 Month Out Hire a wedding planner if desired. Choose your music playlist for your Track RSVPs. reception. Explore ceremony and reception venues, Get your marriage license. checking on potential dates, and reserve. Schedule your final dress fitting. Book your officiant. 3 Months Out Confirm times with all vendors. Explore photographers, DJs or bands, Finalize your menu. Map out your seating plan. florists and caterers.