The Figurative Significance of Intimate Possession in Affinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

'The “I” Inside “Her”': Queer Narration in Sarah Waters's Tipping the Velvet and Wesley Stace's Misfortune

This article was downloaded by: [Emily Jeremiah] On: 07 August 2012, At: 03:44 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Women: A Cultural Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwcr20 ‘The “I” inside “her”’: Queer Narration in Sarah Waters's Tipping the Velvet and Wesley Stace's Misfortune Emily Jeremiah Version of record first published: 25 Jun 2008 To cite this article: Emily Jeremiah (2007): ‘The “I” inside “her”’: Queer Narration in Sarah Waters's Tipping the Velvet and Wesley Stace's Misfortune , Women: A Cultural Review, 18:2, 131-144 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09574040701400171 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

SARAH WATERS's TIPPING the VELVET* María Isabel Romero Ruiz

PROSTITUTION, IDENTITY AND THE NEO-VICTORIAN: SARAH WATERS’S TIPPING THE VELVET* María Isabel Romero Ruiz Universidad de Málaga Abstract Sarah Waters’s Neo-Victorian novel Tipping the Velvet (1998) is set in the last decades of the nineteenth century and its two lesbian protagonists are given voice as the marginalised and “the other.” Judith Butler’s notion of gender performance is taken to its extremes in a story where male prostitution is exerted by a lesbian woman who behaves and dresses like a man. Therefore, drawing from Butler’s theories on gender performance and Elisabeth Grosz’s idea about bodily inscriptions, this article will address Victorian and contemporary discourses connected with the notions of identity and agency as the result of sexual violence and gender abuse. Keywords: violence, prostitution, Tipping the Velvet, bodily inscriptions, performance, Judith Butler, Elisabeth Grosz. Resumen La novela neo-victoriana de Sarah Waters Tipping the Velvet (1998) está situada en las últi- mas décadas del siglo xix y sus dos protagonistas lesbianas reciben voz como marginadas y «las otras». La noción de performatividad de género de Judith Butler es llevada hasta los 187 extremos en una historia donde la prostitución masculina es ejercida por una mujer lesbiana que se comporta y se viste como un hombre. Por tanto, utilizando las teorías de Butler sobre la performatividad del género y la idea de Elisabeth Grosz sobre inscripciones corpóreas, este artículo tratará de acercarse a discursos victorianos y contemporáneos relacionados con las nociones de identidad y agencialidad como resultado de la violencia sexual y el abuso de género. -

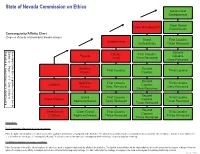

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Criminal Code

2010 Colección: Traducciones del derecho español Edita: Ministerio de Justicia - Secretaría General Técnica NIPO: 051-13-031-1 Traducción jurada realizada por: Clinter Actualización realizada por: Linguaserve Maquetación: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones ORGANIC ACT 10/1995, DATED 23RD NOVEMBER, ON THE CRIMINAL CODE. GOVERNMENT OFFICES Publication: Official State Gazette number 281 on 24th November 1995 RECITAL OF MOTIVES If the legal order has been defined as a set of rules that regulate the use of force, one may easily understand the importance of the Criminal Code in any civilised society. The Criminal Code defines criminal and misdemeanours that constitute the cases for application of the supreme action that may be taken by the coercive power of the State, that is, criminal sentencing. Thus, the Criminal Code holds a key place in the Law as a whole, to the extent that, not without reason, it has been considered a sort of “Negative Constitution”. The Criminal Code must protect the basic values and principles of our social coexistence. When those values and principles change, it must also change. However, in our country, in spite of profound changes in the social, economic and political orders, the current text dates, as far as its basic core is concerned, from the last century. The need for it to be reformed is thus undeniable. Based on the different attempts at reform carried out since the establishment of democracy, the Government has prepared a bill submitted for discussion and approval by the both Chambers. Thus, it must explain, even though briefly, the criteria on which it is based, even though these may easily be deduced from reading its text. -

Garden Paths and Blind Spots

LUCIE ARMITT ON SARAH WATERS’S THE LITTLE STRANGER Garden Paths and Blind Spots When I interviewed Sarah Waters in 2006, I reminded her of an attempt I had made on our first meeting to try and ‘claim’ her as a Welsh Writer. Though now residing in London, she was, of course, born in Pembrokeshire, and I continue to hope to see her to reflect on that aspect of her identity in her fiction. Her response, however, was candid: ‘I love London precisely because I have come to it from a small town in Pembrokeshire – which was a great place to grow up in, but London seemed to me to be the place to go to perhaps slightly re-invent yourself, or to find communities of people – in my case, gay people – that you couldn't find at home.’ 1 In her new novel, The Little Stranger , she does not return to Wales, but she does return to the countryside, setting the novel in the rural Warwickshire village of Lidcote, near Leamington Spa. Waters has, of course, established herself as a writer of lesbian historical fiction and has self-consciously situated her work within a lesbian literary tradition. In the months and weeks prior to the publication of The Little Stranger rumours circulated, allegedly prompted by Waters herself, that there were to be no lesbian characters in it and, indeed, at first sight there are not. The Little Stranger is set just after the end of the Second World War and just before the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948, therefore taking up where the 1947 section of her previous novel, The Night Watch (2006), ends. -

Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers Working Papers 2004 Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ public_law_and_legal_theory Part of the Law Commons Chicago Unbound includes both works in progress and final versions of articles. Please be aware that a more recent version of this article may be available on Chicago Unbound, SSRN or elsewhere. Recommended Citation Elizabeth Emens, "Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence" (University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper No. 58, 2004). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO PUBLIC LAW AND LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 58 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE Elizabeth F. Emens THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO February 2003 This paper can be downloaded without charge at http://www.law.uchicago.edu/academics/publiclaw/index.html and at The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=506242 1 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE 29 N.Y.U. REVIEW OF LAW & SOCIAL CHANGE (forthcoming 2004) Elizabeth F. Emens† Work-in-progress: Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission. I. INTRODUCTION II. COMPULSORY MONOGAMY A. MONOGAMY’S MANDATE 1. THE WESTERN ROMANCE TRADITION 2. -

Kit Stallmann –

Kit Stallmann English 495 Dr. Leslie Werden December 6, 2019 Straight-Jackets: Gay Characters and Mental Asylums Across Times and Cultures, as Portrayed in Film and Literature A historical crime novel written in 2002, an erotic Korean phycological thriller film, and a classic of American literature written by Ken Kesey feature some fascinating shared elements, despite the differences in medium and genre between the three. All take place, in part or whole, inside a mental institute, with characters committed to the institute who are homosexual. Scattered as they are between genres, time periods, context, and settings, they share several obvious connections, namely secrets and deception, unreliable narration, and most, notably, gay characters committed to mental institutions. Although these stories are spread out across times and cultures, each share commonalities of physical and occasionally sexual abuse at the hands of heterosexual medical professionals, and also prominently feature escapes from abusive situations in ways that return the dignity that was taken from each character during their imprisonment. This exchange of abuse for freedom with each character’s sexuality intact shows that authors across cultures understand the vulnerability of homosexual people under the oppressive care of heterosexual medical professionals. Furthermore, the authors, two of whom are straight men and one of whom is a lesbian woman, sympathize with their gay characters and, while allowing them to suffer, also give them an escape that restores their dignity and offers them a happy ending. Fingersmith, a Victorian crime novel written by Sarah Waters in 2002, follows two young women with their own strains of madness. -

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange Edited by Thomas Schweizer University of Cologne Douglas R. White University of California, Irvine CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WEALTH TRANSFERS OCCASIONED BY MARRIAGE: A COMPARATIVE RECONSIDERATION Duran Bell INTRODUCTION The theory of marriage payments has been oriented toward explaining why various categories of practice take place under particular ecological and technological conditions (Bossen 1988; Goody 1973; Spiro 1975; Harrel and Dickey 1985; Kressel 1977; Schlegel and Eloul 1988; Tambiah 1989; and others). This effort has been productive of a wide range of important analytical findings. However, the results of this chapter suggest that some of that work should be reconsidered by reference to a more systematic and scientifically established set of analytical categories. The attempt here is to observe wealth transfers associated with marriage in all forms of society and to reexamine those transfers on the basis of a set of theoretical understandings that have, heretofore, remained only inchoate in theliterature. The principal theoretical issue is the importance of identifying individuals as incumbents of person- categories within socially constructed collectivities. The prevailing analytical perspective tends to present reciprocity as the elementary unit of social action, as is well illustrated by the influential work of Sahlins (1972), and it presents the individual as the elementary social actor. This perspective is related to a view of human action that has deep roots in post-Enlightenment thought, but it constitutes, I believe, a serious disability for the advancement of our understanding of a broad range of social processes. The presentation here makes no attempt to construct a case against the individualist-reciprocity paradigm. -

In Another Time and Place: the Handmaiden As an Adaptation

In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation SHIN, Chi Yun <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0629-6928> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/22714/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version SHIN, Chi Yun (2018). In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema ISSN: 1756-4905 (Print) 1756-4913 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjkc20 In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation Chi-Yun Shin To cite this article: Chi-Yun Shin (2018): In another time and place: TheHandmaiden as an adaptation, Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema, DOI: 10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 19 Sep 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 64 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjkc20 JOURNAL OF JAPANESE AND KOREAN CINEMA https://doi.org/10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781 In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation Chi-Yun Shin Department of Humanities, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article considers the South Korean auteur director Park Chan- The Handmaiden; wook’s latest film The Handmaiden, which is the film adaptation of transnational adaptation; British writer Sarah Waters’s third novel Fingersmith.