The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Testament Theology

1 Seminar in Biblical Literature: Ezekiel (BIB 495) Point Loma Nazarene University Fall 2015 Professor: Dr. Brad E. Kelle Monday 2:45-5:30pm Office: Smee Hall (619)849-2314 [email protected] Office Hours: posted on door “Ah Lord Yahweh! They are saying of me, ‘Is he not always talking metaphors?’” (Ezek 20:49 [Eng.]). “There is much in this book which is very mysterious, especially in the beginning and latter end of it” –John Wesley (Explanatory Notes, 2281). COURSE DESCRIPTION (see also PLNU catalogue) This course engages the student in the study of the book of Ezekiel in English translation. Primary attention will be given to reading Ezekiel from various interpretive angles, examining the book section by section and considering major themes and motifs that run through the book, as well as specific exegetical issues. Instruction will be based upon English translations, although students who have studied Hebrew will be encouraged to make use of their skills. COURSE FOCUS The focus of this course is to provide a broad exegetical engagement with the book of Ezekiel. This engagement will involve study of the phenomenon of prophecy, the general background of Ezekiel the prophet and book, the literary and theological dynamics of the book, and the major interpretive issues in the study of Ezekiel. The aim of the course is to work specifically with the biblical text in light of the historical, social, and religious situation of the sixth century B.C.E. It will also explore, however, the meaning and significance of the literature within Christian proclamation as well as the diverse literary, theological, and methodological issues connected with these texts. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

Lesson 18.Key

Revelation Chapter 17 Lesson 18 Revelation 17:1-2 1 And one from the seven angels, the ones having the seven bowls, came and said to me, “Come, I will show to you the judgment of the great whore, the one seated upon the many waters, 2 with whom the kings of the earth engaged in illicit sex (ἐπόρνευσαν) and the ones dwelling upon the earth got drunk from the wine of her sexual immorality.” Jeremiah 51:6-8 Flee from the midst of Babylon, save your lives, each of you! Do not perish because of her guilt, for this is the time of the LORD’S vengeance; he is repaying her what is due. 7 Babylon was a golden cup in the LORD’S hand, making all the earth drunken; the nations drank of her wine, and so the nations went mad. 8 Suddenly Babylon has fallen and is shattered; wail for her! Bring balm for her wound;perhaps she may be healed. Nahum 3:1-5 1 Ah! City of bloodshed, utterly deceitful, full of booty— no end to the plunder! 2 The crack of whip and rumble of wheel, galloping horse and bounding chariot! 3 Horsemen charging, flashing sword and glittering spear, piles of dead, heaps of corpses, dead bodies without end— they stumble over the bodies! 4 Because of the countless debaucheries of the prostitute, gracefully alluring, mistress of sorcery, who enslaves nations through her debaucheries, and peoples through her sorcery, 5 I am against you, says the LORD of hosts, and will lift up your skirts over your face; and I will let nations look on your nakedness and kingdoms on your shame. -

Divinely Sanctioned Violence Against Women

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY Divinely Sanctioned Violence Against Women Biblical Marriage and the Example of the Sotah of Numbers 5 Johanna Stiebert, University of Leeds Abstract Responding to an important volume by William Cavanaugh (2009), this article argues that biblical violence executed or sanctioned by God or one of his mediators is appropriately designated religious violence. The author looks particularly at gender-based and sexual violence in marriage, challenging some prominent contemporary notions of “biblical marriage.” Focused attention is brought to Num. 5:11-31, detailing the ritual prescribed for the sotah, a woman suspected of adultery. The text is applied both to illuminate religious violence in marriage and to explore and highlight why the ritual, sometimes referred to by biblical interpreters as “strange” or “perplexing,” remains an important topic in our present-day contexts. Key Words Sotah; marriage; adultery; gender-based violence (GBV); intimate partner violence (IPV); religious violence. Introduction In this article I argue that, contrary to the proposal put forth by William Cavanaugh (2009), violence in the Bible can appropriately be designated religious violence. More specifically, I suggest that biblical violence can be classified as religious violence when it is perpetrated by God, or by human mediators who claim to be carrying out God’s instructions, or when it is given divine mandate, or framed by religious justification or religious significance. In the human realm, biblical violence takes numerous forms and is perpetrated by and against men and women. My discussion in this article, however, focuses on divinely sanctioned violence perpetrated by men against women, especially in the context of marriage. -

Aberrant Textuality? the Case of Ezekiel the (Porno) Prophet

ABERRANT TEXTUALITY? THE CASE OF EZEKIEL THE (PORNO) PROPHET Andrew Sloane Summary ‘Pornoprophetic’ readings of the unfaithful wife metaphors in Hosea 1–3, Jeremiah 2 and 3, and Ezekiel 16 and 23 criticise them as misogynistic texts that express and perpetuate negative images of women and their sexuality. This study seeks to present an evangelical response to Athalya Brenner and Fokkelien van Dijk-Hemmes’ pornoprophetic reading of Ezekiel 16 and 23. I outline their claims and supporting arguments, including their assertion that the texts constitute pornographic propaganda which shapes and distorts women’s (sexual) experience in the interests of male (sexual) power. I argue that both their underlying methods and assumptions and their specific claims are flawed, and so their claims should be rejected. While acknowledging the offensive power of the texts, I conclude that alternative explanations such as the violence of Israel’s judgement and the offensive nature of Jerusalem’s sin account better for the features of the texts which they find problematic. 1. Introduction The Old Testament prophets have been an important resource in Christian ethics, particularly in relation to understanding God’s passion for justice—and his corresponding passion that his people reflect that in the conduct of their lives and the patterns of their communities. A recent movement of evangelicals engaging with social justice and advocacy on behalf of the poor derives its name from Micah’s call to 54 TYNDALE BULLETIN 59.1 (2008) justice (Micah 6:6-8).1 Ezekiel’s vision of a new Jerusalem is a vital resource in Revelation’s vision of the new heavens and earth where, in the words of Peter, righteousness is at home (2 Pet. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

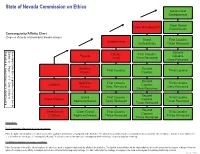

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Criminal Code

2010 Colección: Traducciones del derecho español Edita: Ministerio de Justicia - Secretaría General Técnica NIPO: 051-13-031-1 Traducción jurada realizada por: Clinter Actualización realizada por: Linguaserve Maquetación: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones ORGANIC ACT 10/1995, DATED 23RD NOVEMBER, ON THE CRIMINAL CODE. GOVERNMENT OFFICES Publication: Official State Gazette number 281 on 24th November 1995 RECITAL OF MOTIVES If the legal order has been defined as a set of rules that regulate the use of force, one may easily understand the importance of the Criminal Code in any civilised society. The Criminal Code defines criminal and misdemeanours that constitute the cases for application of the supreme action that may be taken by the coercive power of the State, that is, criminal sentencing. Thus, the Criminal Code holds a key place in the Law as a whole, to the extent that, not without reason, it has been considered a sort of “Negative Constitution”. The Criminal Code must protect the basic values and principles of our social coexistence. When those values and principles change, it must also change. However, in our country, in spite of profound changes in the social, economic and political orders, the current text dates, as far as its basic core is concerned, from the last century. The need for it to be reformed is thus undeniable. Based on the different attempts at reform carried out since the establishment of democracy, the Government has prepared a bill submitted for discussion and approval by the both Chambers. Thus, it must explain, even though briefly, the criteria on which it is based, even though these may easily be deduced from reading its text. -

Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers Working Papers 2004 Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence Elizabeth Emens Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ public_law_and_legal_theory Part of the Law Commons Chicago Unbound includes both works in progress and final versions of articles. Please be aware that a more recent version of this article may be available on Chicago Unbound, SSRN or elsewhere. Recommended Citation Elizabeth Emens, "Monogamy's Law: Compulsory Monogamy and Polyamorous Existence" (University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper No. 58, 2004). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO PUBLIC LAW AND LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 58 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE Elizabeth F. Emens THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO February 2003 This paper can be downloaded without charge at http://www.law.uchicago.edu/academics/publiclaw/index.html and at The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=506242 1 MONOGAMY’S LAW: COMPULSORY MONOGAMY AND POLYAMOROUS EXISTENCE 29 N.Y.U. REVIEW OF LAW & SOCIAL CHANGE (forthcoming 2004) Elizabeth F. Emens† Work-in-progress: Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission. I. INTRODUCTION II. COMPULSORY MONOGAMY A. MONOGAMY’S MANDATE 1. THE WESTERN ROMANCE TRADITION 2. -

Ezekiel 23-28

The Weekly Word Nov 4-10, 2019 Ezekiel continues this week with some tough words. May your reading of God’s Word be blessed this week… Grace and Peace, Bill To hear the Bible read click this link… http://www.biblegateway.com/resources/audio/. Monday, November 4: Ezekiel 23 - Pursuit… How hard God worked to get Israel’s attention. Chapter after chapter, analogy after analogy, the Lord continues to roll out His concern and disgust with Israel’s behavior and the judgment He will impose upon them because of it. Today’s chapter is another indictment for the same sins God has been telling Israel and her leaders about through this book. Will the analogy of two sisters pursuing sex and lovers get through? It seems not. Graphic at times (see verse 20) the Lord did not employ sensibilities laboring to make His point. Additionally, the Lord names some of their most heinous sins, like sacrificing (burning) children in the fire (37 & 39). This is not hyperbole; it is the sin of sacrificing children to Molek. Archaeologists have found evidence of sacrificed children whose remains are placed in jars. How depraved life had become in Israel! Back to my starting point, the Lord tried one method after another to get Israel’s attention inviting them to repent and return. They did not and judgment ultimately fell. The Lord doesn’t change. I believe God pursues people today with similar passion. After coming to faith in Jesus I could look back and see other instances when God did this and that to gain my attention. -

THRU the BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel: Effective Ministry to The

THRU THE BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel: Effective Ministry To The Spiritually Rebellious Part XXXI: God's Disgust Of His People's Idolatrous Reliance On Other People (Ezekiel 23:1-49) I. Introduction A. We often think of idolatry as the pagan worship of a false idol image. However, even in ancient Israel's day, they could do what many people today do -- idolatrously rely on other people instead of God for their needs. B. In Ezekiel 23:1-49, God painted a picture by way of a proverb on how repulsive was His people's idolatrous reliance on other Gentile nations instead of Himself, and we study this passage for our instruction (as follows): II. God's Disgust Of His People's Idolatrous Reliance On Other People, Ezekiel 23:1-49. A. In Ezekiel 23:1-35, God expressed His disgust at Israel's idolatrous reliance on other nations versus Himself: 1. In the form of a parable, the Lord told Ezekiel about two women, sisters as daughters of the same mother, who had committed harlotry in the land of Egypt, Ezekiel 23:1-3. These sisters were the people of Israel in their sojourn in Egypt later to become the Northern Kingdom with its capitol in Samaria, here figuratively named "Oholah," and the Southern Kingdom of Judah with its capitol in Jerusalem, here figuratively named "Oholibah," Ezekiel 23:4. In other words, in Egypt, Jacob's descendants came to rely idolatrously upon the nation of Egypt for protection and sustenance instead of the Lord Himself. 2. "Oholah" (Samaria) means "her tent" and "Oholibah" (Jerusalem) means "my tent is in her," referring to God's sanctuary figuratively mentioned as a "tent" in their midst. -

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange

Kinship, Networks, and Exchange Edited by Thomas Schweizer University of Cologne Douglas R. White University of California, Irvine CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WEALTH TRANSFERS OCCASIONED BY MARRIAGE: A COMPARATIVE RECONSIDERATION Duran Bell INTRODUCTION The theory of marriage payments has been oriented toward explaining why various categories of practice take place under particular ecological and technological conditions (Bossen 1988; Goody 1973; Spiro 1975; Harrel and Dickey 1985; Kressel 1977; Schlegel and Eloul 1988; Tambiah 1989; and others). This effort has been productive of a wide range of important analytical findings. However, the results of this chapter suggest that some of that work should be reconsidered by reference to a more systematic and scientifically established set of analytical categories. The attempt here is to observe wealth transfers associated with marriage in all forms of society and to reexamine those transfers on the basis of a set of theoretical understandings that have, heretofore, remained only inchoate in theliterature. The principal theoretical issue is the importance of identifying individuals as incumbents of person- categories within socially constructed collectivities. The prevailing analytical perspective tends to present reciprocity as the elementary unit of social action, as is well illustrated by the influential work of Sahlins (1972), and it presents the individual as the elementary social actor. This perspective is related to a view of human action that has deep roots in post-Enlightenment thought, but it constitutes, I believe, a serious disability for the advancement of our understanding of a broad range of social processes. The presentation here makes no attempt to construct a case against the individualist-reciprocity paradigm.