Kinship, Networks, and Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Report: the Practice of Dowry and the Incidence of Dowry Abuse in Australia

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Practice of dowry and the incidence of dowry abuse in Australia February 2019 Commonwealth of Australia 2019 ISBN 978-1-76010-898-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. This document was produced by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee secretariat and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Members of the committee Members Senator Louise Pratt (ALP, WA) (Chair) Senator the Hon Ian Macdonald (LNP, QLD) (Deputy Chair) Senator Kimberley Kitching (ALP, VIC) Senator Nick McKim (AG, TAS) Senator Jim Molan AO, DSC (LP, NSW) Senator Murray Watt (ALP, QLD) Participating Members Senator Larissa Waters (AG, QLD) Secretariat Dr Sean Turner, Acting Committee Secretary Ms Nicola Knackstredt, Acting Principal Research Officer Ms Brooke Gay, Administrative Officer Suite S1.61 Telephone: (02) 6277 3560 Parliament House Fax: (02) 6277 5794 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii Table of contents Members of the committee ............................................................................... iii Recommendations .............................................................................................vii Chapter 1............................................................................................................. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad

Journal of Law and Practice Volume 4 Article 3 2011 Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad Charlie Lehmann Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Jaafar-Mohammad, Imani and Lehmann, Charlie (2011) "Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce," Journal of Law and Practice: Vol. 4, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Practice by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Keywords Muslim women--Legal status laws etc., Women's rights--Religious aspects--Islam, Marriage (Islamic law) This article is available in Journal of Law and Practice: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 Jaafar-Mohammad and Lehmann: Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ISLAM REGARDING MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE 4 Wm. Mitchell J. L. & P. 3* By: Imani Jaafar-Mohammad, Esq. and Charlie Lehmann+ I. INTRODUCTION There are many misconceptions surrounding women’s rights in Islam. The purpose of this article is to shed some light on the basic rights of women in Islam in the context of marriage and divorce. This article is only to be viewed as a basic outline of women’s rights in Islam regarding marriage and divorce. -

Strategies for Combating the Culture of Dowry and Domestic Violence in India

pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com "Violence against women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women" Expert Group Meeting Organized by: UN Division for the Advancement of Women in collaboration with: UN Office on Drugs and Crime 17 to 20 May 2005 Vienna, Austria Strategies for Combating the Culture of Dowry and Domestic Violence in India Expert paper prepared by: Madhu Purnima Kishwar Manushi, India 1 This paper deals with the varied strategies used by Manushi and other women’s organizations to deal with issues of domestic violence, the strengths and limitations of approaches followed hitherto and strategies I think might work far better than those tried so far. However, at the very outset I would like to clarify that even though Manushi played a leading role in bringing national attention to domestic violence and the role dowry has come to play in making women’s lives vulnerable, after nearly 28 years of dealing with these issues, I have come to the firm conclusion that terms “dowry death” and “dowry violence” are misleading. They contribute towards making domestic violence in India appear as unique, exotic phenomenon. They give the impression that Indian men are perhaps the only one to use violence out of astute and rational calculations. They alone beat up women because they get rewarded with monetary benefits, whereas men in all other parts of the world beat their wives without rhyme or reason, without any benefits accruing to them. Domestic violence is about using brute force to establish power relations in the family whereby women are taught and conditioned to accepting a subservient status for themselves. -

Women Who Kill Women

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Sturm College of Law: Faculty Scholarship University of Denver Sturm College of Law 2016 Women Who Kill Women Rashmi Goel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/law_facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation 22 Wm & Mary J. Women & L. 549 (2015-2016) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sturm College of Law: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Women Who Kill Women Publication Statement Copyright held by the author. User is responsible for all copyright compliance. This paper is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/law_facpub/40 WOMEN WHO KILL WOMEN RASHMI GOEL* INTRODUCTION I. THE CURIOUS CASES OF WOMEN WHO KILL WOMEN II. THE PROBLEM OF DOWRY DEATHS III. THE INDIAN LEGISLATIVE RESPONSE-PUNISHING PRACTICE WHILE PRESERVING CULTURE A. The Dowry ProhibitionAct of 1961 B. Dowry Harassment and Cruelty: Section 498A C. The Offense of Dowry Death: Section 304B IV. ANSWERING WHY A. The Hurdle of Section 304B B. Beyond Greed 1. Internalized Patriarchy 2. PatriarchalBargain 3. Limited Opportunities to Exercise Power 4. Individual Agency and Autonomy V. GOING FORWARD-DON'T COUNT ON THE COURTS CONCLUSION INTRODUCTION Every hour of every day,1 a woman in India dies over someone's dissatisfaction with her dowry.2 Sometimes she is killed outright, other times the new bride is driven to suicide.3 They call these dowry * Associate Professor of Law, University of Denver, Sturm College of Law. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

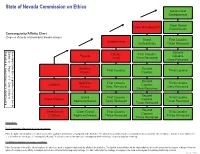

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Criminal Code

2010 Colección: Traducciones del derecho español Edita: Ministerio de Justicia - Secretaría General Técnica NIPO: 051-13-031-1 Traducción jurada realizada por: Clinter Actualización realizada por: Linguaserve Maquetación: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones ORGANIC ACT 10/1995, DATED 23RD NOVEMBER, ON THE CRIMINAL CODE. GOVERNMENT OFFICES Publication: Official State Gazette number 281 on 24th November 1995 RECITAL OF MOTIVES If the legal order has been defined as a set of rules that regulate the use of force, one may easily understand the importance of the Criminal Code in any civilised society. The Criminal Code defines criminal and misdemeanours that constitute the cases for application of the supreme action that may be taken by the coercive power of the State, that is, criminal sentencing. Thus, the Criminal Code holds a key place in the Law as a whole, to the extent that, not without reason, it has been considered a sort of “Negative Constitution”. The Criminal Code must protect the basic values and principles of our social coexistence. When those values and principles change, it must also change. However, in our country, in spite of profound changes in the social, economic and political orders, the current text dates, as far as its basic core is concerned, from the last century. The need for it to be reformed is thus undeniable. Based on the different attempts at reform carried out since the establishment of democracy, the Government has prepared a bill submitted for discussion and approval by the both Chambers. Thus, it must explain, even though briefly, the criteria on which it is based, even though these may easily be deduced from reading its text. -

The Economics of Dowry and Brideprice

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 21, Number 4—Fall 2007—Pages 151–174 The Economics of Dowry and Brideprice Siwan Anderson ayments between families at the time of marriage existed during the history of most developed countries and are currently pervasive in many areas of P the developing world. These payments can be substantial enough to affect the welfare of women and a society’s distribution of wealth. Recent estimates document transfers per marriage amounting to six times the annual household income in South Asia (Rao, 1993), and four times in sub-Saharan Africa (Dekker and Hoogeveen, 2002). This paper first establishes some basic facts about the prevalence and magni- tude of marriage payments. It then discusses how such patterns vary across coun- tries depending upon economic conditions, societal structures, institutions, and family characteristics. Such payments have also evolved within societies over time. For example, in some periods such payments have risen sharply. In some cases, payments have shifted from the grooms’ sides to the brides’, and vice versa. Also, property rights over such payments have sometimes shifted between marrying partners and parental generations. Economists, who have only recently begun to work on the topic, have focused on explaining these facts. The second part of the paper addresses this economic literature. Though considerable insight into many of the facts has been gained, many of the existing economic explanations are weakly convincing, and many puzzles remain. One crucial difficulty is that solid data in this field have been extremely rare. The descriptions of marriage payments in this paper are synthe- sized from a patchwork of studies across periods, places, and even epochs, and there are doubtless numerous cases which remain undocumented. -

The Practice of Dowry and the Incidence of Dowry Abuse in Australia

The practice of dowry and the incidence of dowry abuse in Australia Submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee August 2018 Anti-Slavery Australia Faculty of Law University of Technology Sydney PO Box 123, Broadway NSW 2007 www.antislavery.org.au Anti-Slavery Australia: Submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Inquiry into the practice and incidence of dowry abuse in Australia. August 2018 Contents RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................... 4 1. DOWRY ABUSE ............................................................................................................ 6 1.1. What is dowry? ...................................................................................................... 6 1.2. What is dowry abuse? .......................................................................................... 7 1.3. Prevalence and incidence of dowry abuse internationally ................................. 8 1.4. Prevalence and incidence of dowry abuse in Australia ...................................... 9 1.5. Nexus between dowry abuse and family violence, forced marriage, modern slavery and domestic servitude ................................................................................... 12 1.5.1. Human trafficking, slavery and family violence ............................................. 12 1.5.2. Forced marriage and family violence ............................................................