Representations of Lovesickness in Victorian Literature Viktorya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

The Formation of Interpersonal Attraction and Intimate Relationships on Internet Relay Chat

The Formation of Interpersonal Attraction and Intimate Relationships on Internet Relay Chat An Exploratory Study CHERRIE JOY F. BILLEDO This research investigated the formation of interpersonal attraction and intimate relationships on Internet Relay Chat (IRC). Two methods were employed: survey and in-depth interview. Purposive and convenience sampling were used for both methods. Results revealed that the formation of in-person and online interpersonal attraction and intimate relationships have similar initial stages of development. For online relationships however, partners have to undergo processes to shift from online to in-person. It was also shown that similar attraction cues were important online and in-person. A closer examination, however, showed that these attraction cues differ in salience and quality. This study contributes to the understanding of the impact of computer-mediated communication, particularly IRC, on the development of intimate relationships. The advent of computer-mediated communication (CMC) via the Internet, is believed to have significant implications on various aspects of human endeavor. People are not only meeting and interacting through the Internet; they are forming meaningful relationships as well. According to an article in Newsweek magazine, the phenomenon of online relationships is growing at a fast rate that it now warrants serious attention (Stone 2001). In the Philippines, online romantic relationships are already slowly entering the cultural mainstream through Internet Cherrie Joy F. Billedo is an assistant professor at the Department of Psychology, University of the Philippines Diliman. Email: [email protected] Billedo.p65 1 5/26/2009, 11:02 AM 2 PHILIPPINE SOCIAL SCIENCES REVIEW relay chat (IRC), one form of CMC. -

Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups

Chapter 10 Employee Network and Affinity Groups Employee Network and Affinity Groups n corporate America, a common mission, vision, and purpose in thought and action across Iall levels of an organization is of the utmost importance to bottom line success; however, so is the celebration, validation, and respect of each individual. Combining these two fundamental areas effectively requires diligence, understanding, and trust from all parties— and one way organizations are attempting to bridge the gap is through employee network and affinity groups. Network and affinity groups began as small, informal, self-started employee groups for people with common interests and issues. Also referred to as employee or business resource groups, among other names, these impactful groups have now evolved into highly valued company mainstays. Today, network and affinity groups exist not only to benefit their own group members; but rather, they strategically work both inwardly and outwardly to edify group members as well as their companies as a whole. Today there is a strong need to portray value throughout all workplace initiatives. Employee network groups are no exception. To gain access to corporate funding, benefits and positive impact on return on investment needs to be demonstrated. As network membership levels continue to grow and the need for funding increases, network leaders will seek ways to quantify value and return on investment. In its ideal state, network groups should support the company’s efforts to attract and retain the best talent, promote leadership and development at all ranks, build an internal support system for workers within the company, and encourage diversity and inclusion among employees at all levels. -

The Prevalence and Nature of Unrequited Love

SGOXXX10.1177/2158244013492160SAGE OpenBringle et al. 492160research-article2013 Article SAGE Open April-June 2013: 1 –15 The Prevalence and Nature © The Author(s) 2013 DOI: 10.1177/2158244013492160 of Unrequited Love sgo.sagepub.com Robert G. Bringle1,2, Terri Winnick2,3 and Robert J. Rydell4 Abstract Unrequited love (UL) is unreciprocated love that causes yearning for more complete love. Five types of UL are delineated and conceptualized on a continuum from lower to greater levels of interdependence: crush on someone unavailable, crush on someone nearby, pursuing a love object, longing for a past lover, and an unequal love relationship. Study 1a found all types of UL relationships to be less emotionally intense than equal love and 4 times more frequent than equal love during a 2-year period. Study 1b found little evidence for limerent qualities of UL. Study 2 found all types of UL to be less intense than equal love on passion, sacrifice, dependency, commitment, and practical love, but more intense than equal love on turmoil. These results suggest that UL is not a good simulation of true romantic love, but an inferior approximation of that ideal. Keywords unrequited love, interdependence, love, friendship Although virtually all aspire to consummate romantic love, Baumeister et al., 1993). Interdependence encompasses the path toward achieving the ideal love relationship is lit- influence, behavioral control, and the frequency, diversity, tered with relationships that are incomplete approximations. and length of interaction (Berscheid, Snyder, & Omoto, Many of these are discarded, whereas some relationships are 2004). Berscheid and Ammazzalorso (2001) posited that maintained in spite of their imperfections. -

Lovesickness” in Late Chos Ǒn Literature

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reinterpreting “Lovesickness” in Late Chos ǒn Literature A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Janet Yoon-sun Lee 2014 © Copyright by Janet Yoon-sun Lee 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reinterpreting “Lovesickness” in Late Chos ǒn Literature By Janet Yoon-sun Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Peter H. Lee, Chair My dissertation concerns the development of the literary motif of “lovesickness” (sangsa py ǒng ) in late Chos ǒn narratives. More specifically, it examines the correlation between the expression of feelings and the corporeal symptoms of lovesickness as represented in Chos ǒn romance narratives and medical texts, respectively, of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As the convergence of literary and medical discourse, lovesickness serves as a site to define both the psychological and physical experiences of love, implying the correlation between mind and body in the non-Western tradition. The analysis itself is re-categorized into the discussions of the feeling and the body. In the discussion of the feeling, it will be argued that the feeling of longing not only occupies an important position in literature, but also is gendered and structured in lyrics and narratives of the seventeenth century. In addressing the rubric of feelings of “longing,” this part seeks the ii theoretical grounds of how the intense experience of longing is converted to language of love and to bodily symptoms to constitute the knowledge of lovesickness. The second part concerns the representation of lovesick characters in Korean romance, particularly concerning the body politics of the Chos ŏn society. -

The Unrequited Love As Reflected in William Blake's “Love's Secret”

1 THE UN5(4UITED L29( AS REF/ECTED IN WIL/IAM B/$.E‘S —L29(‘S SECRET“ Submitted by: Olivia Fergie Risthania 13020110110008 ABSTRACT The purpose of this final academic paper is to describe the love story which tells sadness in :illiam Blake‘s —Love's Secret“. The writer adopts Erich Fromm‘s theory of unrequited love from The Art of Loving. This final academic paper concerns intrinsic and extrinsic side of the poem. In the intrinsic side, the writer discusses about the existing diction and figurative language such as denotation and connotation and imagery to understand the true meaning of the poem. The extrinsic side, the writer discusses about unrequited love. The writer used library research, note-taking and internet browsing for collecting the data. The result is that love does not only bring happiness but also deep sadness for the speaker of the poem as unrequited love which is reflected in —/ove's Secret“. So, it succeeds in bringing the readers to feel what the speaker feels. Keywords: Love, Diction, Figurative Language, Unrequited Love, Deep Sadness 1. Introduction Poetry is universal because there are a lot of topics can be shown, for example: love, family, life, sadness, happiness, death, marriage and others. Those issues are the reflection of the ordinary life which the ordinary person is concerned. In all ages and in some countries, poetry has been regarded as one of important thing in human‘s existence. Love is an incredibly powerful word. This word is so easy to say, but it has a great meaning and feeling to every human being. -

Elvis Presley Once Sang, "Wise Men Say Only Fools Rush In, but I Can't

Laws of Attraction - Ruth 2:5-22 Dr. Kevin D. Glenn – Lead Pastor Elvis Presley once sang, "Wise men say only fools rush in, but I can't help falling in love with you." Have you ever noticed the language we use when we describe the beginning of romantic relationships? We use so many phrases about relationships that imply a loss of control: "Swept off my feet," "intoxicated," "falling in love," "fell for you.", etc. With all this stumbling and falling, no wonder relationships can hurt so much! This morning we’ll witness the beginning moments in the relationship between Ruth and Boaz. How do their first encounters help us re-examine the ways we relate when we’re interested in someone? What principles can we take from their interaction to help us, whether we’re married, divorced, or single? What are some laws of attraction seen in this part of the story? 1. Use your head to guide your heart. There is nothing wrong with being aware of your initial chemistry with someone. However, looks can fade, change, or be surgically altered…We must look below the skin for admirable qualities, qualities that will either confirm or betray outward appearances. • Many of today’s dating practices actually hinder our ability to really know a person. • Ignoring your head to follow your feelings can lead to a broken heart. • Ask questions, get history, look for patterns. Be smart, not just smitten. Boaz asked the foreman of his harvesters, "Whose young woman is that?" 6 The foreman replied, "She is the Moabitess who came back from Moab with Naomi. -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

Human-Computer Interaction and Sociological Insight: a Theoretical Examination and Experiment in Building Affinity in Small Groups Michael Oren Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups Michael Oren Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Oren, Michael, "Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12200. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human-computer interaction and sociological insight: A theoretical examination and experiment in building affinity in small groups by Michael Anthony Oren A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Co-Majors: Human Computer Interaction; Sociology Program of Study Committee: Stephen B. Gilbert, Co-major Professor William F. Woodman, Co-major Professor Daniel Krier Brian Mennecke Anthony Townsend Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Michael Anthony Oren, 2011. All -

Broken Heart

(see: drugs, doing too many). Keep your eyes on the dream, but also on each rung of the ladder. B 56 See alSo: disenchantment • hope, loss of • broken friendship broken friendship See: friend, falling out with your best broken heart As It Is in Heaven Rare is the person who goes through life with their heart Niall WilliamS intact. Once the arrow has flown from Cupid’s bow and struck Jane Eyre its target, quivering with a mischievous thrill, there begins Charlotte Brontë a chemical reaction that despatches its victim on a journey filled with some of life’s most sublime pleasures but also its most tormented pitfalls (see: love, doomed; love, unrequited; lovesickness; falling out of love with love; and, frankly, most of the other ailments in this book). Nine times out of ten,* romance is dashed on the rocks and it all ends in tears. Why so cynical? Because literature bursts with heart- break like so many aortic aneurisms. You can barely pick up a novel that does not secrete the grief of a failed romance, or the loss of a loved one through death, betrayal or some-such unforeseen disaster. Heartbreak doesn’t just afflict those on the outward journey; it can strike even when you thought you were safely stowed (see also: adultery; divorce; and death of a loved one). Those afflicted have no choice, at least initially, but to sit down with a big box of tissues, another of choco- lates, and a novel that will open up the tear ducts and allow you to cry yourself a river. -

What's Love Got to Do with It: Courtship in Antebellum

WHAT’S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT: COURTSHIP IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY TAYLOR M. GARRISON Honors Thesis Muhlenberg History Department Dr. Lynda Yankaskas 6 May 2020 Garrison 2 In June of 1826, Edward Dickinson proposed to Emily Norcross via letter. A month later, Norcross had yet to accept, Dickinson poured out his affections for her across even more pages. He wrote: “I am perfectly satisfied in relation to your character & your virtues—and were you as well satisfied that our union would promote our mutual happiness, I would most cheerfully offer you my heart & hand—will you accept them?”1 No parents had been consulted for input nor had there been any discussion of economic exchange. Instead, Dickinson proposed marital happiness by means of his hand, economic and legal attachment, and his heart, companionship and emotional connection. In offering Norcross his hand and heart, Dickinson forsook the courtship traditions of the past and embraced the spirit of the American Revolution. Young adults in post-Revolutionary America exercised semi-independence from their parents.2 There was greater acceptance of young adult’s independent decisions through society-at-large’s push for democratic equality. Thus, society afforded them the power to make many of their own social choices. The rise of the Industrial Revolution further supported semi-independence by pushing many young adults to work outside the family home. Despite the growing societal support for young adults’ freedom, many courting Americans depended upon their family for essentials, such as economic support and physical housing. While young adults primarily constructed their own beliefs about courtship and marriage, they were cognizant of their continuing dependence on their families and adjusted their behavior accordingly. -

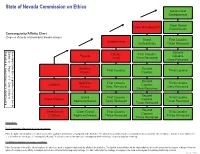

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage.