Opinion Leaders and (In)Civility in the Wake of School Shootings Deana A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Andrea Karch the Issue of Radicalization Might Be a Bitter-Tasting Stigma of Generation-Ym, “Bills of Capi- Talism” (Charles Taylor)

“I had the time of my life” Andrea Karch The issue of radicalization might be a bitter-tasting stigma of Generation-Ym, “bills of capi- talism” (Charles Taylor). At the same time the mainstream media seems to play tug-of-war between the description of an ideologically brainwashed individual and the idea of “the mass murderer next door”. News, ripe for the boulevard press and social media platforms. A clear typography of radicalized youth is impossible, though. But in a society in which the dematerialization of value and meaning seems to be a general trend, the phenomenon of young individuals that turn towards models of violence as their dernier ressort to self-identifi- cation, might be a result of just the same. IDENTITY A photo of a buff, male Neo-Nazi. His head is white, round and shaved. He has got jug ears, his mouth is opened slightly and crooked, his chin is extraordinarily large. He wears a blue Pitt Bull T-Shirt and Levis Jeans, jump boots and suspenders. He holds a leash with a light grey poodle at the end of it. This image probably is photoshopped. The New York Post’s cover photo allegedly portrays Hasna Ait Boulahcen, the first female suicide bomber who died in a raid fol- lowing the Paris attacks. Covered in a bubble bath, the shown woman is nude. The cover title is “Rub a dub dub... THUG IN A TUB”. Her whole story later turned out to have been a fake. Alexandre Bissonette’s last facebook post before he commits the Quebec city mosque shooting 2017, shows a dog wearing a Dominos pizza delivery outfit with the caption “I want one! #fridayfeeling.” An ISIS fighter holds a delicate kitten in his arms: ISILCats@Twitter “My Mewjahid protectz me”. -

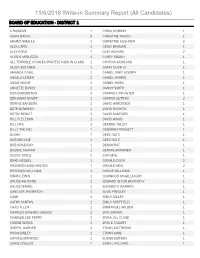

11/6/2018 Write-In Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD of EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1

11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 A RAINEAR 1 CHRIS MURRAY 1 ADAM HATCH 2 CHRISTINE ASHOO 1 AHMED SMALLS 1 CHRISTINE KUSHNER 2 ALEX CARR 1 CINDY BEAMAN 1 ALEX FORD 1 CLAY WILKINS 2 ALICE E VERLEZZA 1 COREY BRUSH 1 ALL TERRIBLE CHOICES PROTECT KIDS IN CLASS 1 CYNTHIA WOOLARD 1 ALLEN BUTCHER 1 DAFFY DUCK III 1 AMANDA GOWL 1 DANIEL GREY SCURRY 1 ANGELA LEISER 2 DANIEL HARRIS 1 ANGIE WIGHT 1 DANIEL HORN 1 ANNETTE BUSBY 1 DANNY SMITH 1 BEN DOBERSTEIN 2 DAPHNE LANCASTER 1 BENJAMIN DOVER 1 DAPHNE SUTTON 2 BERNIE SANDERS 1 DAVID HARDISTER 1 BETH BOWMAN 1 DAVID RUNYON 1 BETSY BENOIT 1 DAVID SANFORD 1 BILL FLELEHAN 1 DAVID WOOD 1 BILL NYE 1 DEANNE TALLEY 1 BILLY THE KID 1 DEBORAH PRICKETT 1 BLANK 7 DEEZ NUTS 1 BOB MELONE 1 DEEZ NUTZ 1 BOB SPAZIANO 1 DEMOCRAT 1 BOBBIE CAVNAR 1 DENNIS BRAWNER 1 BOBBY JONES 1 DON MIAL 1 BRAD HESSEL 1 DONALD DUCK 2 BRANDON WASHINGTON 1 DONALD MIAL 2 BRANNON WILLIAMS 1 DONNE WILLIAMS 1 BRIAN LEWIS 1 DURWOOD MCGILLACUDY 1 BRUCE ASHFORD 1 EDWARD ALTON HUNTER IV 1 BRUCE MAMEL 1 ELIZABETH WARREN 1 CANDLER THORNTON 1 ELVIS PRESLEY 1 CASH 1 EMILY JOLLEY 1 CATHY SANTOS 1 EMILY SHEFFIELD 1 CHAD ALLEN 1 EMMANUEL WILDER 1 CHARLES EDWARD CHEESE 1 ERIC BROWN 1 CHARLES LEE PERRY 1 ERIKA JILL CLOSE 1 CHERIE WIGGS 1 ERIN E O'LEARY 1 CHERYL GARNER 1 ETHAN MATTHEWS 1 CHRIS BAILEY 1 ETHAN SIMS 1 CHRIS BJORNSTED 1 EUSHA BURTON 1 CHRIS COLLUM 1 EVAN L POLLARD 1 11/6/2018 Write-in Summary Report (All Candidates) BOARD OF EDUCATION - DISTRICT 1 EVERITT 1 JIMMY ALSTON 1 FELIX KEYES 1 JO ANNE -

Uitdagers Van De Gevestigde Orde

9] culture wars 2.0 - uitdagers van de gevestigde orde ICT heeft gezorgd voor een informatie-explosie die alle aspecten van het moderne leven beinvloeden: economie, politiek, overheid, media, onderwijs, gezondheid en het persoonlijke en sociale leven van burgers ICT heeft de samenleving ingrijpend veranderd: we leven thans in een informatie-maatschappij, "waarin de creatie, verspreiding, gebruik, integratie en manipulatie van informatie een belangrijke economische, politieke en culturele activiteit is" 1 de digitale revolutie, aangezwengeld door informatie & communicatie-technologie, wordt gekenmerkt door: ➢ een ongekende hoeveelheid informatie die ter beschikking komt voor iedereen met een internet-verbinding dit heeft geleid tot verdere emancipatie van de burger: burgers hebben toegang tot oneindig veel informatie dit maakt de burger meer (niet perse beter) geïnformeerd (via news-feeds, en alles is te ‘Googelen’) 2 daarbij kunnen zij zelf ook informatie delen (in theorie met de hele wereld, in praktijk met gelijkgestemden) ➢ enorme macht voor grote tech-bedrijven (Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc) die floreren op big data ICT biedt instituties / overheden ongekende mogelijkheden tot vergaring en manipulatie van informatie ook andere (non-tech) bedrijven en overheden maken gebruik van big data voor marketing en monitoring de informatie-samenleving zorgt zo voor nieuwe machts-ongelijkheid ➢ concurrentie voor gevestigde instituties; m.n. voor conventionele massa-media (krant, tijdschriften, TV, radio) deze concurrentie leidt tot een ondermijning -

The Oxygen of Amplification Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online

The Oxygen of Amplification Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online By Whitney Phillips EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MAPPING THE MEDIA ECOSYSTEM We live in a time where new forms of power are emerging, where social and digital media are being leveraged to reconfigure the information landscape. This new domain requires journalists to take what they know about abuses of power and media manipulation in traditional information ecosystems and apply that knowledge to networked actors, such as white nationalist networks online. These actors create new journalistic stumbling blocks that transcend attempts to manipulate reporters solely to spin a beneficial narrative – which reporters are trained to decode – and instead represent a larger effort focused on spreading hateful ideology and other false and misleading narratives, with news coverage itself harnessed to fuel hate, confusion, and discord. The choices reporters and editors make about what to cover and how to cover it play a key part in regulating the amount of oxygen supplied to the falsehoods, antagonisms, and manipulations that threaten to overrun the contemporary media ecosystem—and, simultaneously, threaten to undermine democratic discourse more broadly. This context demands that journalists and the newsrooms that support them examine with greater scrutiny how these actors and movements endeavor to subvert journalism norms, practices, and objectives. More importantly, journalists, editors, and publishers must determine how the journalistic rule set must be strengthened and fortified against this newest form of journalistic manipulation—in some cases through the rigorous upholding of long-standing journalistic principles, and in others, by recognizing which practices and structural limitations make reporters particularly vulnerable to manipulation. -

The Hypermodern Anti-Comedy of Tim and Eric, Eric André and Million Dollar Extreme

“The Dada of Haha”: The Hypermodern Anti-Comedy of Tim and Eric, Eric André and Million Dollar Extreme Alexandra Warrick The Department of Film Studies, Columbia University Professor Richard Pena February 1st, 2016 1 SMASHING THE LIVING ROOM: AN INTRODUCTION Potted plants, a couch. A desk, a chair. Brown curtains, columns, a tabletop globe. Picture a comedy talk show set outfitted with these staples: homey, right? Comforting? It might, for you, invoke a living room; after all, as Michael Shapiro writes, “the family-like living room of the talk-show set…functions as a theatrical stage to forge intimate connections with the friends and family of the nation.” (Shapiro 32) Think, for a moment, on the worn-in “living rooms” offered by our nation’s most beloved comedy programs: the quirky clutter of Seinfeld, the stylized skyline of the Tonight Show, the comforting glow of Saturday Night Live’s faux-Grand Central spread. We know these spaces perhaps better than we do our own living rooms; the latter mutable, the former dependable. We come upon these shared “living rooms” and we, Pavlov’s audience, know that it’s time to laugh. Comedy becomes a warm, bubbling cordial that brings us, the Shapiro-style nation-as-family, together; in indulging in our shared national sense of humor, we as a culture bond together as we settle into the cozy cosmic couch these comedy programs offer us. With this in mind, once again picture the comedy talk show set. Now picture a man bursting from the wings to violently, viciously kick it to pieces. -

To Troll the Media How a Cartoon Frog Became a Hate Symbol Bachelor's

To Troll the Media How a cartoon frog became a hate symbol Bachelor’s Thesis Ville Suomela University of Jyväskylä Department of Language and Communication Studies English June 2019 Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta Kieli- ja viestintätieteiden laitos Tekijä – Author Ville Suomela Työn nimi – Title To Troll the Media: How a cartoon frog became a hate symbol Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Englannin kieli Kandidaatintutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Kesäkuu 2019 30 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Pepe-sammakko on yksi kaikista tunnetuimmista internet-meemeistä ja sitä on aktiivisesti käytetty jo 11 vuotta erilaisilla sosiaalisen median alustoilla, YouTubessa sekä reaaliaikaiseen suoratoistoon pohjautuvassa Twitchissä. Vuonna 2016 tämä meemi lisättiin yllättäen Anti- Defamation Leaguen (ADL) tietokantaan vihasymbolina. Tämän tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää, kuinka tämä kaikki tapahtui. Tutkielmaa varten aineistona on käytetty kolmea eri uutisartikkelia, jotka sijoittuivat ajallisesti Pepe-sammakon uuden merkityksen muodostumisen ympärille. Lisäksi analysoitavana on muutamia otteita meemin käytöstä ennen ja jälkeen tämän uuden kategorisoinnin. Lähestymistavaksi ja tutkielman teoreettiseksi taustaksi valitsin lähteitä identiteettien rakentumisesta, kriittisestä diskurssianalyysistä sekä media-analyysistä ja median representaatioista. Lopputuloksena vaikuttaisi siltä, että niin kutsutut ”trollit” olivat manipuloineet media-alan ammattilaisia sosiaalisessa mediassa -

On the Cultural Inaccessibility of Gaming: Invading, Creating, and Reclaiming the Cultural

On the Cultural Inaccessibility of Gaming: Invading, Creating, and Reclaiming the Cultural Clubhouse by Emma Vossen A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2018 © Emma Vossen 2018 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Dr. Todd Harper Assistant Professor Supervisor(s) Dr. Neil Randall Associate Professor Internal Member Dr. Aimée Morrison Associate Professor Internal-external Member Dr. Shana MacDonald Assistant Professor Other Member(s) Dr. Jennifer R. Whitson Assistant Professor ii Authors Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This dissertation uses intersectional feminist theory and Autoethnography to develop the concept of “cultural inaccessibility”. Cultural inaccessibility is a concept I’ve created to describe the ways that women are made to feel unwelcome in spaces of game play and games culture, both offline and online. Although there are few formal barriers preventing women from purchasing games, playing games, or acquiring jobs in the games industry, this dissertation explores the formidable cultural barriers which define women as “space invaders” and outsiders in games culture. Women are routinely subjected to gendered harassment while playing games, and in physical spaces of games culture, such as conventions, stores, and tournaments. -

How Misinformation Spreads Through Twitter

Capstone Projects & Student Papers Brookings Mountain West 2020 How Misinformation Spreads Through Twitter Mary Blankenship University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/ brookings_capstone_studentpapers Part of the Public Policy Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Repository Citation Blankenship, M. (2020). How Misinformation Spreads Through Twitter. 1-28. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_capstone_studentpapers/6 This Capstone Project is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Capstone Project in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Capstone Project has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects & Student Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW MISINFORMATION SPREADS THROUGH TWITTER Mary Blankenship University of Nevada, Las Vegas ABSTRACT While living in the age of information, an inherent drawback to such high exposure to content lends itself to the precarious rise of misinformation. Whether it is called “alternative facts,” “fake news,” or just incorrect information, because of its pervasiveness in nearly every political and policy discussion, the spread of misinformation is seen as one of the greatest challenges to overcome in the 21st century. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 47, No. 05

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus NOTRE DAME IMll JULY-AUGUST, 1969 Nonviolence or Nonexistence? The University Attempts an Answer VoL 47 No. 5 Joly-August 1969 James D. Cooney EXECUTIVE SEOIETAKV ALUMNI ASSOCIATION For your informatioii John P. Thurin '59 EonaK This is my first opportunity to welcome you to the magazine and it's a Tom Sulltvan '66 pleasure. You may notice some marked variations in both style and quality — MANACINO EDITOR hopefully pleasing — this time around, mainly because we've got a penchant Sandn Loiufoote for experimentation and because for the first time we were able to utilize the ASSISTANT EDITOB offset printing method to produce the ALUMNUS. We hope you have the Jeannine Doty EDITOUAL ASSISTANT patience to bear with us in our continuing search for that piece de resistence M. Bruce Harbn '49 in style. Though it may seem we've been a bit on the inconsistent side, we CHIEF PHOTOCKAFHEK feel each issue brings us closer to our objective. ALIJMNI ASSOCIATION OFTICERS This, our mid-summer effort, is devoted in large part to a feature on the Richaid A. Rosenthal '54 University's new program for the nonviolent resolution of human conflict. HONOHAItV FkESIDENT Leonard H. Skoglund '38 The program is a unique academic venture with implications that seem terribly niESniENT relevant in a society swollen with cruelty and violence. Prof. Charles Edwaid G. CantweU '24 McCarthy, the program director, sheds light on interesting aspects of the VlCE-BttSIDENT program and the problem with which it will be concerned. -

The Oxygen of Amplification Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online

The Oxygen of Amplification Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online By Whitney Phillips PART 1 In Their Own Words Trolling, Meme Culture, and Journalists’ Reflections on the 2016 US Presidential Election CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................... 3 On Assessing the “Alt-Right” ........................................................... 10 The 4chan Connection ...................................................................... 14 The Troll-Trained Versus Not Troll-Trained Distinction..................... 19 An Inferno of Far-Right Extremism ................................................... 23 On Seeing Wolves, But Not Seeing Trolls ........................................ 26 Internet Literacy and Amplification: A Foreshadowing ................... 31 Acknowledgments .............................................................................. 35 Endnotes................ .............................................................................. 36 Works Cited........... .............................................................................. 40 Author: Whitney Phillips; PhD 2012, English with an emphasis on folklore, University of Oregon This report is funded by Craig Newmark Philanthropies and News Integrity Initiative, with additional programmatic and general support from other Data & Society funders. For more information, please visit https://datasociety.net/about/#funding. Access the full report at http://datasociety.net/output/oxygen-of-amplification/ -

A Cut Above: the End (And Ends) of Film Censorship

A CUT ABOVE: THE END (AND ENDS) OF FILM CENSORSHIP by Daniel Vincent Sacco Master of Fine Arts York University, Toronto, Ontario, 2010 Bachelor of Arts Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, 2007 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 ©Daniel Sacco 2017 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University and York University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research I further authorize Ryerson University and York University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract A CUT ABOVE: THE END (AND ENDS) OF FILM CENSORSHIP Daniel Vincent Sacco Doctor of Philosophy Ryerson University and York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 By the beginning of the twenty-first century in the West, the notion of government-appointed bodies mandated for censoring cinematic content had fallen considerably out of fashion as institutional censorship was largely curtailed. Barring widely shared concerns regarding the exposure of underage children to material deemed inappropriate, newly rebranded “classification” boards have acted to limit the extent to which they themselves can prohibit images from entering the public market, shifting their emphasis away from censorship and toward consumer edification and greater consideration of artistic merit and authorial intent.