The Hypermodern Anti-Comedy of Tim and Eric, Eric André and Million Dollar Extreme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gregg Turkington on What He Learned from Punk Rock

June 13, 2017 - Gregg Turkington is best known for his "anti-comedy" character, Neil Hamburger. The Australian actor co-stars in the film review web series "On Cinema at the Cinema" with Tim Heidecker and is the co-writer and co-star of the Adult Swim series, Decker. He had a part in the 2015 film Ant-Man, and that same year, starred in Entertainment, a drama he co-wrote. In the 1990s, he ran the music label, Amarillo Records, and played in bands like Caroliner, Zip Code Rapists, Faxed Head, and has released a number of albums as Neil Hamburger, mostly on the Chicago independent music label, Drag City. He contributed artwork and live recordings to Flipper's Public Flipper Limited Live 1980-1985. As told to Charlie Sextro, 2383 words. Tags: Culture, Music, Comedy, Inspiration, Beginnings, Independence. Gregg Turkington on what he learned from punk rock I’m interested to hear how your fascination with showmanship began. As a kid, how interested were you in entertainment? Super interested. Initially really with music, and then I got more into movies. I was a complete obsessive about all the things I liked. I grew up in Tempe, Arizona. I was really into Phil Ochs. He was my absolute idol. I was really into the Bee Gees and The Who. Then I got really into a revival, repertoire theater, The Valley Art. It was like $2 or something and I would pretty much go to any movie that was playing, to see what was going on. Then when I saw something that interested me, I would go over to the campus at ASU. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

President Biden Spotted in Trump Statue Park Kissing Bronze Hair of Shirley Temple //DIANA KOLSKY

FEB 8, 2021//VOL. IV, ISSUE 3 BRB, gearing up for the ensuing Pillow Fights. 2 FD Exclusive: Governor Cuomo to COVID Task Force: “Have We Tried Peeing on the Virus?” //JAMES DWYER 4 President Biden Spotted in Trump Statue Park Kissing Bronze Hair of Shirley Temple //DIANA KOLSKY 5 The Trade-In Value on this Gamestop Stock Sucks //BRADY O'CALLAHAN 6 Where Are The $2,000 Checks? We’re Building an Army of Harriet Tubman Clones to Deliver Them as We Speak //MATTHEW BRIAN COHEN 8 Pitchfork Reviews Ariel Pink & John Maus Debut Collaboration, We The People //MICHAEL "PORTLAND MIKE" KNACKSTEDT GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 10 Paid Advertisement: The Cancelled Crate™ //THE FUNCTIONALLY DEAD HEADS 11 This Quarantine Valentine’s Day, Give Them a Gift They’ll Love: One Goddamn Day Alone //AMANDA PORYES GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 13 14 Functionally Dead Investment Newsletter: Think Like A Stock //MATTHEW BRIAN COHEN 15 Salute to Our Inessential Workers //THE FUNCTIONALLY DEAD HEADS 18 Marriage Is a Capitalist Institution, Mom (and I Can't Find Anyone Who Likes Me for Me) //ANDREW BARLOW GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 20 Dr. Jill Biden Gave Me CPR, and I Died for Seven Minutes //DIANA KOLSKY 21 Teen Militia Member Weighs Pros and Cons of Listing His Oath Keepers Affiliation on College Application //CAMILLE TINNIN GUEST CONTRIBUTOR 23 What Do I Do Now? //DAN LOPRETO THIS IS A MAGAZINE OF PARODY, SATIRE, AND OPINION//DESIGNED BY DIANA KOLSKY 1 FD EXCLUSIVE Governor Cuomo to COVID Task Force: “Have We Tried Peeing on the Virus?” //JAMES DWYER FD has secured access to a recording from a recent phone call between NY Governor Andrew Cuomo and his COVID Task Force. -

Mister America

Presents MISTER AMERICA A film by Eric Notarnicola 86 mins, USA, 2019 Language: English Distribution Mongrel Media Inc 217 – 136 Geary Ave Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filming took place on location in San Bernardino and the Los Angeles area. Using a mix of actors and non-actors, the small crew used documentary techniques to give the experience of a true story unfolding in real time. Often filming in four to five locations a day and using a script in which specific dialogue was scarce but the intention for each scene was detailed, actors improvised fully in the moment to allow their characters to develop naturally. What resulted was a team in-sync and fully ready to capture the chaotic world around them. 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com 1. ABOUT THE CAST As one half of comedy duo “Tim and Eric” and creator of Abso Lutely Productions, Tim Heidecker can easily be viewed as a godfather of subversive, alt-comedy. With roles in “Us”, “Eastbound & Down”, “Awesome Show”, “Portlandia” and more, Mr. Heidecker has helped to affect the comedy landscape for years to come. As a co-creator of On Cinema and its ensuing worlds with Gregg Turkington, he’s been able to prod at multiple facets of society. -

2015 Year in Review

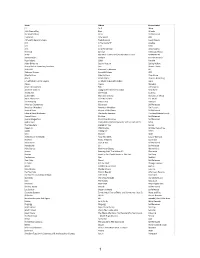

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Meeting of the Administrative Rules Review Committee

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE RULES REVIEW COMMITTEE Time of The regular meeting of the Administrative Rules Review Meeting Committee was held Tuesday and Wednesday, July 11 and 12, 1989, Committee Room 22, State Capitol, Des Moines, Iowa. Members Senator Berl E. Priebe, Chairman; Representative Emil S. Present Pavich, Vice Chairman; Senators Donald v. Doyle and Dale L. Tieden; Representative David Schrader. Absent due to illness, Representative Betty Jean Clark. Staff present: Joseph A. Royce, Counsel; Phyllis Barry, Administrative Code Editor; Vivian Haag, Executive Secretary. Also preseni:: Barbara Brooker Burnett, Governor's Adminis trative Rules Coordinator; Evelyn Hawthorne, Democratic Caucus. Meeting Chairman Priebe convened the Committee at 10 a.m., Tuesday, Convened July 11, 1989, Senate Committee Room 22. The following rules of Disaster Services were before the Committee: Disaster services - enhanced 911 tclephonl! systems, ch 10, ~·A llC 91;r;o ........... · · · · · · · · · ·. · · · · · · · · · · •·. · · · .... · · 6/28!1i9 PUBLIC DEFENSE Present for the discussion were Ellen Gordon, Director; DEPARTMENT David L. Miller and Jerry L. Ostendorf; Charles E. Hinkle, Humboldt County; Kenneth J. Hartman, Hartman and Associ ates, Boone. Gordon explained that rules addressing enhanced 911 telephone systems were mandated by legislation. A hearing on the rules resulted in changes being made. Chairman Priebe recognized Hartman, who was representing Humboldt, Mahaska, Washington, Dallas, Buchanan and Web ster Counties. Hartman offered what he believed to be constructive criticism and referenced a critique which he had mailed to ARRC members. Areas of disagreement included 10.8(3) which requires approval of the plan modifications and addenda by the Division prior to im plementation. -

Stage Door Theatre's Season 48 Auditions

STAGE DOOR THEATRE’S SEASON 48 AUDITIONS WHO? Stage Door Theatre is seeking actors, performers, and improvisers of multiple identities and abilities. All parts are compensated/paid. WHERE? 5339 Chamblee Dunwoody Rd. Dunwoody, GA 30338 WHEN? August 7th @ 11 am – 5 pm. Please click on the following link to reserve your slot: https://forms.gle/rdLnhsB96MGANSGy6 (callbacks may be held August 8th, if necessary). WHAT? Stage Door Theatre is auditioning for the following: - A Midsummer Night’s Dream (tracks listed at the end of this section) • Rehearses August 12th-September 3rd; Performs September 4th and 5th • Please prepare one 60 second Shakespearean monologue Oberon/Theseus Lysander/Flute/Cobweb Egeus/Starveling/Mote - Stage Door Theatre’s resident Improv/Sketch Comedy Troupe • Rehearses T-TH in September, October, December, February, April • Performs in November, January, March, May, June • Prepare one 60 sec. Story and one 60 sec. comic monologue in verse - Stage Door Theatre’s Season 48 tracks • Looking for actors ages 40+ • Prepare 2 contrasting monologues in verse and 16 bars of a Golden Age Musical or operetta SHOW DATES TRACK 1 TRACK 2 TRACK 3 TRACK 4 Romeo and Reh: Sep. Capulet Nurse Friar Lady Capulet Juliet Per: Oct Lawrence Halloween Reh: Oct various various various various Cabaret Per: Oct A Christmas Reh: Nov Scrooge Christmas various Christmas Carol Per: Dec Present Past Importance Reh: Jan Merriman Ms. Prism Reverend Lady Of Being Per: Feb Chausuble Bracknell Earnest Valentine’s Reh: Feb various various various various Day Cabaret Per: Feb The Pirates Reh: March Sergent of Ruth Major TBD of Penzance Per: April Police General Stanley . -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Comedy Series A.P. Bio Gary Meets Dave Jack loses Helen’s money that she needs for the school mascot Pam the Ram’s surgery so he tells her it was stolen. The students help Jack try get the cash back. Meanwhile, Stef, Mary and Michelle run into trouble with their mall-walking group. Richie Keen, Directed by A.P. Bio Katie Holmes Day Jack vows to ruin the local holiday, Katie Holmes Day, because he’s jealous that a fellow Toledoan achieved their dreams. Meanwhile, Durbin is determined not to flub his line in the pageant this year. Mary and Stef run the holiday rummage sale. Anu Valia, Directed by B Positive Pilot Drew, a recently divorced father, discovers he needs a kidney and finds his donor in the last person he ever would've imagined. James Burrows, Directed by black-ish Our Wedding Dre Dre's (Anthony Anderson) intimate wedding plans for Pops (Laurence Fishburne) and Ruby (Jenifer Lewis) go awry when Pops' brother, Uncle Norman, (Danny Glover) shows up unexpectedly for the festivities. Meanwhile Ruby refuses Bow's (Tracee Ellis Ross) offer to help with preparations. Eric Dean Seaton, Directed by black-ish Please, Baby, Please Dre tries to soothe baby DeVante back to sleep by reading him a bedtime story that becomes a story expressing his own concerns about the state of our country. Kenya Barris, Directed by Breeders No Fear Luke’s anxiety is becoming a problem at home and school. Would a medical diagnosis make his life easier or harder? Ally faces further tension after her mother Leah is robbed. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Reference No. Collection Site

PASSPORTS APPLIED IN PCG DUBAI/FSPsRCOsManila/VFS(PaRC) PASSPORTS READY FOR RELEASE AS OF 29 August 2021 RELEASING SECTION 8-12NN, 1-5PM, SUN-THU, EXCEPT HOLIDAYS TO SEARCH FOR YOUR NAME press "CONTROL F" OR "F3". If your name is already listed, please proceed to your designated Collection Site with your OLD PASSPORT AND OFFICIAL RECEIPT to claim your new e- passport. If the applicant cannot come personally to collect the passport, authorize someone to pick-up the passport. The following are the requirements: AUTHORIZATION LETTER, OLD PASSPORT, ORIGINAL RECEIPT, AND ORIGINAL AND COPY OF VALID IDENTIFICATION CARD OF AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE. WRITE THE REFERENCE NUMBER AT THE TOP OF YOUR RECEIPT UPON CLAIMING YOUR PASSPORT Middle Collection Last name First name Reference No. name Site AARTS ESRA MAE R. 2000106100360 DubaiPCG ABABA ROLANDO JR. I. 2000134000360 DubaiPCG ABACAN RENELYN D. 2000122300360 DubaiPCG ABAD MARIA EMMA D. 2000120550360 DubaiPCG ABAD CRISALDO B. 2000121900360 DubaiPCG ABAD ARIANNE FAYE D. 2000016765000 PaRC ABAD MICHELLE JANE D. 2000135890360 DubaiPCG ABAD MA. LAVINIA R. 2000037215000 PaRC ABAD SARAH T. 2000037435000 PaRC ABAD GERALD E. 2000137190360 Dubai PCG ABAD PAOLO NOEL R. 2000038495000 PaRC ABADILLA JOJO A. 2000017505000 PaRC ABAGAT LILIA D. 2000037825000 PaRC ABALAYAN AUDREIL O. 2000017855000 PaRC ABALAYAN MILDRED O. 2000017865000 PaRC ABALLE JESIE FE S. 2000136280360 Dubai PCG ABALOS ARRA BELLA J. 2000019735000 PaRC ABALOS BLENS RADIEL S. 2000136930360 Dubai PCG ABALOS LIZA C. 2000037855000 PaRC ABALOS ALDRIN D. 2000038055000 PaRC ABALUS XYNE AUBRIELLE C. 2000124910360 DubaiPCG ABANICO DANILO JR. M. 2000106680360 DubaiPCG ABAO DANIEL V. 2000120610360 DubaiPCG ABAO MARY LYN A. -

EMILY TING 2008 N ALVARADO STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90039 TEL: 651.442.2545 EMAIL: [email protected]

EMILY TING www.emilyting.com 2008 N ALVARADO STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90039 TEL: 651.442.2545 EMAIL: [email protected] SELECTED CREDITS TELEVISION 2016 Costume Designer Broken Thank You, Brain! / ABC Digital 2016 Costume Designer Comedy Bang! Bang! Abso Lutely Productions / IFC 2015 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 4 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2015 Costumer Why? With Hannibal Buress Comedy Central 2014 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 3 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer Check It Out! With Dr. Steve Brule Season 3 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer Hannibal Buress: Unemployable (Pilot) JAX Media / Comedy Central 2013 Costume Designer Candy Ranch (Pilot) Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim 2013 Costume Designer The Eric Andre Show Season 2 Abso Lutely Productions / Adult Swim ADVERTISING 2016 Costume Designer Eric Andre at the RNC and DNC Promos Abso Lutely Productions 2015 Costume Designer USAA: Car Buying Service Sandwich Video 2015 Costume Designer Ruffles: Ridgiculous HeLo 2015 Costume Designer Toyota Camry: Fatherʼs Day Video Buzzfeed 2015 Costume Designer Why? With Hannibal Buress Promos Comedy Central 2014 Costume Designer American Legacy: Erase and Replace PSA Abso Lutely Productions 2013 Costume Designer Guinness : The Colorful World of Black Prologue 2013 Costume Designer Motorola: Tim and Ericʼs First Vacation Jash 2013 Costume Designer Nick Offerman Paddle Your Own Canoe Promo Funny or Die 2013 Costume Designer Groupon: Imagine Sandwich Video 2013 Costume Designer Zipcar: Wheels When You Want Them Sandwich Video 2013 Costume Designer Intel: Big Box Odd Machine FEATURE FILM 2011 Wardrobe Supervisor Nancy, Please Small Coup Films / dir. -

Nickelodeon's Groundbreaking Hit Comedy Icarly Concludes Its Five-Season Run with a Special Hour-Long Series Finale Event, Friday, Nov

Nickelodeon's Groundbreaking Hit Comedy iCarly Concludes Its Five-season Run With A Special Hour-long Series Finale Event, Friday, Nov. 23, At 8 P.M. (ET/PT) Carly Shay's Air Force Colonel Father Appears for First Time in Emotional Culmination of Beloved Series SANTA MONICA, Calif., Nov. 14, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Nickelodeon's groundbreaking and beloved hit comedy, iCarly, which has entertained millions of kids and made random dancing and spaghetti tacos pop culture phenomenons, will end its five- season run with an unforgettable hour-long series finale event on Nickelodeon Friday, Nov. 23, at 8 p.m. (ET/PT) . (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20121114/NY13645 ) In "iGoodbye," Spencer (Jerry Trainor) offers to take Carly (Miranda Cosgrove) to the Air Force father-daughter dance when their dad, Colonel Shay, isn't able to accompany her because of his overseas deployment. When Spencer gets sick and can't take her, Freddie (Nathan Kress) and Gibby (Noah Munck) try to cheer Carly up by offering to go with her. Colonel Shay surprises everyone when he arrives just in time to take Carly to the dance. When they return from their wonderful evening together, Carly is disappointed to learn her dad must return to Italy that evening and she is faced with a very difficult decision. "iCarly has been a truly definitional show that was the first to connect the web and TV into the fabric of its story-telling, and we are so very proud of it and everyone who worked on it," said Cyma Zarghami, President, Nickelodeon Group. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name First Paper Second Paper

LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME FIRST PAPER SECOND PAPER Stynsberg Oscar V14, P4 Styrcula John V21, P19 Styrzula John V21, P19 Styscz Anton V23, P56 V23, P56 Stysez Anton B1, F2, P267 Stysz Anton V23, P56 V23, P56 Subic Frank V8, P93 Succhetti Pietro V10, P116 Succhetti Pietro V13, P875 Succhetti Pietro V15, P1049 Succoli Buskin V13, P815 Suchal Vilma B6, F4, P2627 Sucoli Buskin V15, P974 Sudak John V30, P9 Suderland S. V8, P397 Suenaert Victor V10, P152 Suenaert Victor V13, P838 Suenaert Victor V15, P1002 Suino Henry V13, P673 Suino Henry V15, P773 Sullivan John E. V8, P186 Sullivan John E. V14, P382 Sullivan John E. V11, P10 Sullivan Thomas V8, P151 Sunaert Victor V10, P152 Sund Carl Martinsen B1, F1, P100 Sundberg August V8, P414 Sundberg August V16, P329 Sundberg Ole V8, P294 Sundberg Ole V13, P852 Thursday, August 05, 2004 Page 498 of 568 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME FIRST PAPER SECOND PAPER Sundberg Ole V15, P1020 Sunderlund John V8, P64 Sunderson Fed V10, P313 Sundholm Jonas Sigfrid B1, F3, P332 Sundholm Jonas Sigfrid B1, F3, P332 Sundholm Jonas Sigfrid V22, P181 V22, P181 Sundin Alfred V8, P179 Sundin Aug. V14, P260 Sundin August V12, P247 Sundin Daniel V8, P269 Sundin Erik Axel V10, P277 Sundin John V8, P120 Sundin Magnus V8, P288 Sundin Walfred V10, P268 Sundling Mary Swanson B6, F4, P2608 Sundling Selma B3, F3, P2112 Sundling Selma B5, F3, P2176 Sundquist Andreio V15, P653 Sundquist Andrew V12, P585 Sundquist Andrew V8, P57 Sundquist John V21, P38 V21, P38 Sundquist M. V11, P26 Sundquist M.