FOREWORD. What Thomas Hobbes Knows About Today's Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Download-Pdf

AN ANALYSIS OF ECLECTIC THEATRE IN IRAN BASED ON TA’ZIYEH FARIDEH ALIZADEH CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University 2015of Malaya AN ANALYSIS OF ECLECTIC THEATRE IN IRAN BASED ON TA’ZIYEH FARIDEH ALIZADEH THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University of Malaya 2015 UNIVERSITI MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Farideh Alizadeh Registration/Matric No: RHA110003 Name of Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis (“this Work”): An Analysis of Eclectic Theatre in Iran Based on Ta’ziyeh Field of Study: Drama/Theatre I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor ought I reasonably to know that the making of this Work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (‘UM’), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

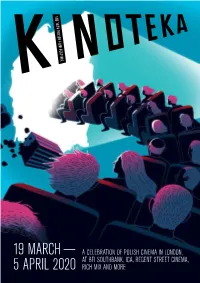

Kinoteka2020 Guide-Compressed.Pdf

Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 kinoteka.org.u k Welcome to Kinoteka 18! Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO KINOTEKA 18! Welcome to KINOTEKA 18! ................................................................ 1 As we enter a new decade, Polish film documentaries with a trio of recent films, continues to go from strength to strength. spanning topics such as loneliness, Japanese While Agnieszka Holland, that tireless voice students’ struggles with learning the Polish SCREENINGS & EVENTS from the old guard of Polish film-making, language, and romantic intimacy among the Opening Night Gala ....................................................................... 4 continues to channel her vision with Mr. tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto. New Polish Cinema ........................................................................ 6 Jones, a number of newer talents have broken We continue to bring you the best in through – most notably, screenwriter Mateusz exclusive cinematic experiences with a Documentaries ............................................................................ 12 Pacewicz and actor Bartosz Bielenia in Corpus series of interactive events and showcases Focus: Richard Boleslawski ............................................................... 16 Christi, Poland’s short-listed entry for this encompassing the breadth of cinema history. Family Event .............................................................................. 18 year’s Academy Awards. At the 18th Kinoteka The Cinema Museum focuses on the early Tadeusz Kantor -

Iti-Info” № 4 (25) 2014

RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE «МИТ-ИНФО» № 4 (25) 2014 “ITI-INFO” № 4 (25) 2014 УЧРЕЖДЁН НЕКОММЕРЧЕСКИМ ПАРТНЕРСТВОМ ПО ПОДДЕРЖКЕ ESTABLISHED BY NON-COMMERCIAL PARTNERSHIP FOR PROMOTION OF ТЕАТРАЛЬНОЙ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ И ИСКУССТВА «РОССИЙСКИЙ THEATRE ACTIVITITY AND ARTS «RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ЦЕНТР МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ИНСТИТУТА ТЕАТРА». INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE» ЗАРЕГИСТРИРОВАН ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЙ СЛУЖБОЙ ПО НАДЗОРУ В СФЕРЕ REGISTERED BY THE FEDERAL AGENCY FOR MASS-MEDIA AND СВЯЗИ И МАССОВЫХ КОММУНИКАЦИЙ. COMMUNICATIONS. СВИДЕТЕЛЬСТВО О РЕГИСТРАЦИИ REGISTRATION LICENSE SMI PI № FS77-34893 СМИ ПИ № ФС77-34893 ОТ 29 ДЕКАБРЯ 2008 ГОДА OF DECEMBER 29TH, 2008 АДРЕС РЕДАКЦИИ: 129594, МОСКВА, EDITORIAL BOARD ADDRESS: УЛ. ШЕРЕМЕТЬЕВСКАЯ, Д. 6, К. 1 129594, MOSCOW, SHEREMETYEVSKAYA STR., 6, BLD. 1 ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ ПОЧТА: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] НА ОБЛОЖКЕ: СЦЕНА ИЗ СПЕКТАКЛЯ «БОЕВОЙ КОНЬ» COVER: “WAR HORSE” BY MARIANNE ELLIOT/TOM MORRIS. КОРОЛЕВСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ТЕАТРА ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ, ROYAL NATIONAL THEATRE ПОСТАНОВКА: МЭРИЭНН ЭЛЛИОТТ И ТОМ МОРРИС OF GREAT BRITAIN ФОТО: BRINKHOFF/MOEGENBURG PHOTO BY BRINKHOFF/MOEGENBURG ФОТОГРАФИИ ПРЕДОСТАВЛЕНЫ ОТДЕЛОМ ПО СВЯЗЯМ С PHOTOS ARE PROVIDED BY PR DEPARTMENT ОБЩЕСТВЕННОСТЬЮ И РЕКЛАМЕ ВСЕРОССИЙСКОГО МУЗЕЙНОГО OF MUSEUM ASSOCIATION OF MUSICAL CULTURE NAMED ОБЪЕДИНЕНИЯ МУЗЫКАЛЬНОЙ КУЛЬТУРЫ ИМ. М. И. ГЛИНКИ, AFTER M. GLINKA, PRESS SERVICES OF THE PETR FOMENKO ПРЕСС-СЛУЖБАМИ ТЕАТРА «МАСТЕРСКАЯ ПЕТРА ФОМЕНКО», WORKSHOP AND CHEKHOV INTERNATIONAL THEATRE FESTIVAL, МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ТЕАТРАЛЬНОГО ФЕСТИВАЛЯ ИМ. А. П. ЧЕХОВА, CHRISTOPHE RAYNAUD DE LAGE, OLEG CHERNOUS, CHRISTOPHE RAYNAUD DE LAGE, ОЛЕГОМ ЧЕРНОУСОМ, MARINA MARINA BALYSH, ALEXANDER IVANISHIN, BALYSH, АЛЕКСАНДРОМ ИВАНИШИНЫМ, MANIA ZYZAK MANIA ZYZAK DITOR IN HIEF LFIRA ГЛАВНЫЙ РЕДАКТОР: АЛЬФИРА АРСЛАНОВА E - -C : A ARSLANOVA DITOR IN HIEF EPUTY LGA ЗАМ. -

The Vocabulary of Acting: a Study of the Stanislavski 'System' in Modern

THE VOCABULARY OF ACTING: A STUDY OF THE STANISLAVSKI ‘SYSTEM’ IN MODERN PRACTICE by TIMOTHY JULES KERBER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine the extent to which the vocabulary of acting created by Konstantin Stanislavski is recognized in contemporary American practice as well as the associations with the Stanislavski ‘system’ held by modern actors in the United States. During the research, a two-part survey was conducted examining the actor’s processes while creating a role for the stage and their exposure to Stanislavski and his written works. A comparison of the data explores the contemporary American understanding of the elements of the ‘system’ as well as the disconnect between the use of these elements and the stigmas attached to Stanislavski or his ‘system’ in light of misconceptions or prejudices toward either. Keywords: Stanislavski, ‘system’, actor training, United States Experienced people understood that I was only advancing a theory which the actor was to turn into second nature through long hard work and constant struggle and find a way to put it into practice. -

Stage Actors and Modern Acting Methods Move to Hollywood in the 1930S

Document generated on 10/02/2021 5:28 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Stage Actors and Modern Acting Methods Move to Hollywood in the 1930s L’arrivée à Hollywood, dans les années 1930, des acteurs de théâtre et des techniques de jeu modernes Cynthia Baron L’acteur entre les arts et les médias Article abstract Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2014 In this article, the author considers factors in commercial 1930s American theatre and film which led to the unusual circumstance of many stage-trained URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1030232ar actors employing ostensibly theatrical acting methods to respond effectively to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1030232ar the challenges and opportunities of industrial sound film production. The author proposes that with American sound cinema fundamentally changing See table of contents employment prospects on Broadway and Hollywood production practices, the 1930s represent a unique moment in the history of American performing arts, wherein stage-trained actors in New York and Hollywood developed performances according to principles of modern acting articulated by Publisher(s) Stanislavsky, the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York and the Cinémas acting manuals written by theatre-trained professionals and used by both stage and screen actors. To illustrate certain aspects of the era’s conception of modern acting, the author analyzes a scene from Captains Courageous (Victor ISSN Flemining, 1937) with Spencer Tracy and a scene from The Guardsman (Sidney 1181-6945 (print) Franklin, 1931) with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Baron, C. -

Beyond Realism: Into the Studio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons Beyond Realism: Into the Studio Tom Cornford Shakespeare Bulletin, Volume 31, Number 4, Winter 2013, pp. 709-718 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/shb/summary/v031/31.4.cornford.html Access provided by University of York (10 Dec 2013 06:02 GMT) Epilogue Beyond Realism: Into the Studio TOM CORNFORD University of York As a director, a teacher of actors and directors, and––most of all––as an audience member, I am often confounded by the ubiquity of realist aesthetics in the Anglophone theater. The original political force of the idea of showing life-as-it-is-lived has long since drained away, and we have somehow become trapped within its husk.1 On the other hand, as a scholar of theater practice (and as a theater maker whose practice has been profoundly altered by that scholarship), I cannot help but be aware that the discipline in which I work owes a great debt to realism. That obligation is part of a still-greater debt to the Russian actor, director, and teacher Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky, whose “system” is gener- ally acknowledged to be the first comprehensive attempt to extend the widespread understanding of the art of acting and our capacity to teach and explore it further. In these concluding thoughts to this issue, I will explore the roots of Stanislavsky’s “system” in his enduring commitment to the Studio as the creative center of theater making. -

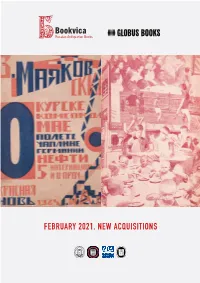

February 2021. New Acquisitions F O R E W O R D

FEBRUARY 2021. NEW ACQUISITIONS F O R E W O R D Dear friends & colleagues, We are happy to present our first catalogue of the year in which we continue to study Russian and Soviet reality through books, magazines and other printed materials. Here is a list of contents for your easier navigation: ● Architecture, p. 4 ● Women Studies, p. 19 ● Health Care, p. 25 ● Music, p. 34 ● Theatre, p. 40 ● Mayakovsky, p. 49 ● Ukraine, p. 56 ● Poetry, p. 62 ● Arctic & Antarctic, p. 66 ● Children, p. 73 ● Miscellaneous, p. 77 We will be virtually exhibiting at Firsts Canada, February 5-7 (www.firstscanada.com), andCalifornia Virtual Book Fair, March 4-6 (www.cabookfair.com). Please join us and other booksellers from all over the world! Stay well and safe, Bookvica team February 2021 BOOKVICA 2 Bookvica 15 Uznadze St. 25 Sadovnicheskaya St. 0102 Tbilisi Moscow, RUSSIA GEORGIA +7 (916) 850-6497 +7 (985) 218-6937 [email protected] www.bookvica.com Globus Books 332 Balboa St. San Francisco, CA 94118 USA +1 (415) 668-4723 [email protected] www.globusbooks.com BOOKVICA 3 I ARCHITECTURE 01 [HOUSES FOR THE PROLETARIAT] Barkhin, G. Sovremennye rabochie zhilishcha : Materialy dlia proektirovaniia i planovykh predpolozhenii po stroitel’stvu zhilishch dlia rabochikh [i.e. Contemporary Workers’ Dwellings: Materials for Projecting and Planned Suggestions for Building Dwellers for Workers]. Moscow: Voprosy truda, 1925. 80 pp., 1 folding table. 23x15,5 cm. In original constructivist wrappers with monograph MB. Restored, pale stamps of pre-war Worldcat shows no Ukrainian construction organization on the title page, pp. 13, 45, 55, 69, copies in the USA. -

Acting: the First Six Lessons

Acting: The First Six Lessons Acting: The First Six Lessons is a key text for drama students today. These dramatic dialogues between the teacher and “the Creature”—an idealistic student—explore the “craft” of acting according to one of the godfathers of method acting. The book also features Boleslavsky’s lec- tures to The Creative Theatre and American Laboratory Theatre, as well as “Acting with Maria Ouspenskaya,” four short essays on the work of Ouspenskaya, his colleague and fellow actor trainer. This new edition is edited with an introduction and bibliography by Rhonda Blair, author of The Actor, Image, and Action. Richard Boleslavsky (1889–1937) (born Ryszard Boleslawski) was a Polish actor and director. He was a member of the Moscow Art Theatre and director of its First Studio. He emigrated to New York in the 1920s and was the first teacher of the Stanislavski system of acting in the West. He went on to produce plays on Broadway and was a leading Hollywood director in the 1930s. Rhonda Blair is Professor of Theatre at Southern Methodist University. She is a leading voice on the applications of cognitive science on the acting process and the author of The Actor, Image, and Action: Acting and Cognitive Neuroscience. She is currently the President of the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR). Acting: The First Six Lessons Documents from the American Laboratory Theatre Richard Boleslavsky Edited and introduced by Rhonda Blair 711 Third Avenue, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10017 Contents Acknowledgments viii Editor’s introduction ix Acting: -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College The

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By ANDREA V. JOHNSON Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Barbara Fast, Chair Dr. Jane Magrath, Co-Chair Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Igor Lipinski Dr. Rockey Robbins Dr. Click here to enter text. © Copyright by ANDREA V. JOHNSON 2019 All Rights Reserved. AKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this document and degree would have been impossible without the guidance and support of my community. Foremost, I wish to express my gratitude to my academic committee including current and past members: Dr. Jane Magrath, Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Eugene Enrico, Dr. Igor Lipinski, Dr. Caleb Fulton, and Dr. Rockey Robbins. Dr. Magrath, thank you for your impeccable advice, vision, planning, and unwavering dedication to my development as a pianist and teacher. You left no stone unturned to ensure that I had the support necessary for success at OU and I remain forever grateful to you for your efforts, your kindness, and your commitment to excellence. My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Fast for serving as chair of this committee, for your support throughout the degree program, and for many conversations with valuable recommendations for my professional development. Dr. Enrico, thank you for your willingness to serve on my committee and for your suggestions for the improvement of this document. -

The Chicano Theatre Movement and Actor Training in the United States

FROM LA CARPA TO THE CLASSROOM: THE CHICANO THEATRE MOVEMENT AND ACTOR TRAINING IN THE UNITED STATES Dennis Sloan A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Tim Brackenbury Graduate Faculty Representative Angela K. Ahlgren Cynthia Baron © 2020 Dennis Sloan All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor The historical narrative of actor training has thus far been limited to the history of Eurocentric actor training. Put another way, it has been predominantly white. While the history of actor training has been understudied in general, the history of training for actors of color has been almost non-existent. Yet scholars including Alison Hodge and Mark Evans have made direct links between actor training and both the evolution of theatre and the development of personal, artistic, and socio-political worldviews. Since the recorded history of actor training focuses almost exclusively on white practitioners, however, this history privileges the experiences and perspectives of white practitioners over those of color. Rooted in the argument that a history of actor training based so exclusively on whiteness is incomplete and inaccurate, this dissertation explores the history of actor training for Latinx actors, especially those who participated in and came out of the Chicanx Theatre Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and who went on to engage in other training programs afterwards. Relying primarily on original archival research, I document multifaceted attempts to train Latinx actors in the United States in the mid- to late twentieth century.