Download-Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Analysis of Vocal Ornamentation in Iranian Classical Music

437 Analysis of Vocal Ornamentation in Iranian Classical Music Sepideh Shafiei Graduate Center, City University of New York [email protected] ABSTRACT There are two main recorded vocal radifs sung by two mas- ters of the art during the twentieth century: Davami¯ and In this paper we study tahrir, a melismatic vocal ornamen- Karimi. tation which is an essential characteristic of Persian classi- cal music and can be compared to yodeling. It is consid- Tahrir is rapid transition between the main note and a ered the most important technique through which the vo- higher-pitched note. The second note is usually referred calist can display his/her prowess. In Persian, nightingale’s to as tekyeh, which means leaning in Persian. From sig- song is used as a metaphor for tahrir and sometimes for a nal processing perspective one of the differences between specific type of tahrir. Here we examine tahrir through tahrir and vibrato is that the pitch rises and fall in tahrir is a case study. We have chosen two prominent singers of usually sharper and the deviation from the main notes can Persian classical music one contemporary and one from be larger compared to vibrato [3]. Also, the oscillation in the twentieth century. In our analysis we have appropri- vibrato is toward both higher and lower frequency around ated both audio recordings and transcriptions by one of the the main note, but in tahrir mainly the higher frequency most prominent ethnomusicologists, Masudiyeh, who has is touched abruptly. There are different types of tahrir in worked on Music of Iran [1]. -

Life Science Journal 2013;10(9S) Http

Life Science Journal 2013;10(9s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Studying Mistaken Theory of Calendar Function of Iran’s Cross-Vaults Ali Salehipour Department of Architecture, Heris Branch, Islamic Azad University, Heris, Iran [email protected] Abstract: After presenting the theory of calendar function of Iran’s cross-vaults especially “Niasar” cross-vault in recent years, there has been lots of doubts and uncertainty about this theory by astrologists and archaeologists. According to this theory “Niasar cross-vault and other cross-vaults of Iran has calendar function and are constructed in a way that sunrise and sunset can be seen from one of its openings in the beginning and middle of each season of year”. But, mentioning historical documentaries we conclude here that the theory of calendar function of Iran’s cross-vaults does not have any strong basis and individual cross-vaults had only religious function in Iran. [Ali Salehipour. Studying Mistaken Theory of Calendar Function of Iran’s Cross-Vaults. Life Sci J 2013;10(9s):17-29] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 3 Keywords: cross-vault; fire temple; Calendar function; Sassanid period 1. Introduction 2.3 Conformity Of Cross-Vaults’ Proportions With The theory of “calendar function of Iran’s Inclined Angle Of Sun cross-vaults” is a wrong theory introduced by some The proportion of “base width” to “length of interested in astronomy in recent years and this has each side” of cross-vault, which is a fixed proportion caused some doubts and uncertainties among of 1 to 2.3 to 3.9 makes 23.5 degree arch between researchers of astronomy and archaeologists but the edges of bases and the visual line created of it except some distracted ideas, there has not been any which is equal to inclining edge of sun. -

Pdf 734.61 K

Mathematics Interdisciplinary Research 5 (2020) 239 − 257 The Projection Strategies of Gireh on the Iranian Historical Domes Ahad Nejad Ebrahimi ? and Aref Azizpour Shoubi Abstract The Gireh is an Islamic geometric pattern which is governed by mathe- matical rules and conforms to Euclidean surfaces with fixed densities. Since dome-shaped surfaces do not have a fixed density, it is difficult to make use of a structure like Gireh on these surfaces. There are, however, multiple domes which have been covered using Gireh, which can certainly be thought of a remarkable achievement by past architects. The aim of this paper is to discover and classify the strategies employed to spread the Gireh over dome surfaces found in Iran. The result of this research can provide new insights into how Iranian architects of the past were able to extend the use of the Gireh from flat surfaces to dome-shaped elements. The result of this paper reveal that the projection of Gireh on dome surface is based on the following six strategies: 1- Spherical solids, 2- radial gore segments, 3- articulation, 4- changing Gireh without articulating, 5- changing the number of Points in the Gireh based on numerical sequences, and 6- hybrid. Except for the first method, all of the other strategies have been discovered in this study. The radial gore segments strategy is different from the previously-developed methods. Keywords: Islamic mathematics, geometry, Gireh, domical surface, pattern pro- jection How to cite this article A. Nejad-Ebrahimi and A. Azizpour-Shoubi, The projection Strategies of Gireh on the Iranian Historical domes, Math. -

Itinerary Brilliant Persia Tour (24 Days)

Edited: May2019 Itinerary Brilliant Persia Tour (24 Days) Day 1: Arrive in Tehran, visiting Tehran, fly to Shiraz (flight time 1 hour 25 min) Sightseeing: The National Museum of Iran, Golestan Palace, Bazaar, National Jewelry Museum. Upon your pre-dawn arrival at Tehran airport, our representative carrying our show card (transfer information) will meet you and transfer you to your hotel. You will have time to rest and relax before our morning tour of Tehran begins. To avoid heavy traffic, taking the subway is the best way to visit Tehran. We take the subway and charter taxis so that we make most of the day and visit as many sites as possible. We begin the day early morning with a trip to the National Museum of Iran; an institution formed of two complexes; the Museum of Ancient Iran which was opened in 1937, and the Museum of the Islamic Era which was opened in 1972.It hosts historical monuments dating back through preserved ancient and medieval Iranian antiquities, including pottery vessels, metal objects, textile remains, and some rare books and coins. We will see the “evolution of mankind” through the marvelous display of historic relics. Next on the list is visiting the Golestan Palace, the former royal Qajar complex in Iran's capital city, Tehran. It is one of the oldest historic monuments of world heritage status belonging to a group of royal buildings that were once enclosed within the mud-thatched walls of Tehran's Arg ("citadel"). It consists of gardens, royal buildings, and collections of Iranian crafts and European presents from the 18th and 19th centuries. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 369 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Martin, Klaas Flechsig, Larissa Chu, Leigh Dehaney, OUR READERS Leonie Gavalas, Lianne Bosch, Lisandra Ilisei, Luis Many thanks to the travellers who used the last Maia, Luzius Thuerlimann, Maarten Jan Oskam, edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, useful Maksymilian Dzwonek, Manfred Henze, Marc Verkerk, advice and interesting anecdotes: Adriaan van Dijk, Marcel Althaus, Marei Bauer, Marianne Schoone, Adrian Ineichen, Adrien Bitton, Adrien Ledeul, Agapi Mario Sergio Dd Oliveira Pinto, Marjolijn -

Iranian Bazaars and the Social Sustainability Of

Journal of Construction in Developing Countries (Early View) This PROVISIONAL PDF corresponds to the article upon acceptance. Copy edited, formatted, finalised version will be made available soon. Manuscript Title Iranian Bazaars and the Social Sustainability of Modern Commercial Spaces in Iranian Cities Authors Kimia Ghasemi, Mostafa Behzadfar and Mahdi Hamzenejad Submitted Date 04-Mar-2020 (1st Submission) Accepted Date 30-Jun-2020 EARLY VIEW © Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia. This work is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Iranian Bazaars and the Social Sustainability of Modern Commercial Spaces in Iranian Cities Kimia Ghasemi, Mostafa Behzadfar and Mahdi Hamzenejad School of Architecture & Urban Development, Iran University of Science & Technology, Tehran, Iran Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract: According to some factors such as participation, interactions, identification and security, Iran’s traditional bazaars are good examples of social sustainability. In fact, bazaars are not considered as merely an economic environment but also an environment for many social activities due to their status and their location in the important environments and centers of the city and the significant role and social status of market’s businessmen in the city. However, in the modern industrial era and with appearance of new urban elements, it can be observed that many spaces for commuting and many urban traditional environments took important social-cultural functions. Under these circumstances, this research used the descriptive analytical method to focus on evaluating the environments of persistent traditional social business centers in order to achieve persistence in modern social business centers through evaluating and studying the historical background of business centers, urban services and traditional elements that form them. -

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Edited by Halim Rane Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Editor Halim Rane MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Halim Rane Centre for Social and Cultural Research / School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science Griffith University Nathan Australia Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) (available at: www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ Australia muslim). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-1222-8 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-1223-5 (PDF) © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Preface to ”Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” ........................ ix Halim Rane Introduction to the Special Issue “Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” Reprinted from: Religions 2021, 12, 314, doi:10.3390/rel12050314 .................. -

Iti-Info” № 4 (25) 2014

RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE «МИТ-ИНФО» № 4 (25) 2014 “ITI-INFO” № 4 (25) 2014 УЧРЕЖДЁН НЕКОММЕРЧЕСКИМ ПАРТНЕРСТВОМ ПО ПОДДЕРЖКЕ ESTABLISHED BY NON-COMMERCIAL PARTNERSHIP FOR PROMOTION OF ТЕАТРАЛЬНОЙ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ И ИСКУССТВА «РОССИЙСКИЙ THEATRE ACTIVITITY AND ARTS «RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ЦЕНТР МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ИНСТИТУТА ТЕАТРА». INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE» ЗАРЕГИСТРИРОВАН ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЙ СЛУЖБОЙ ПО НАДЗОРУ В СФЕРЕ REGISTERED BY THE FEDERAL AGENCY FOR MASS-MEDIA AND СВЯЗИ И МАССОВЫХ КОММУНИКАЦИЙ. COMMUNICATIONS. СВИДЕТЕЛЬСТВО О РЕГИСТРАЦИИ REGISTRATION LICENSE SMI PI № FS77-34893 СМИ ПИ № ФС77-34893 ОТ 29 ДЕКАБРЯ 2008 ГОДА OF DECEMBER 29TH, 2008 АДРЕС РЕДАКЦИИ: 129594, МОСКВА, EDITORIAL BOARD ADDRESS: УЛ. ШЕРЕМЕТЬЕВСКАЯ, Д. 6, К. 1 129594, MOSCOW, SHEREMETYEVSKAYA STR., 6, BLD. 1 ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ ПОЧТА: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] НА ОБЛОЖКЕ: СЦЕНА ИЗ СПЕКТАКЛЯ «БОЕВОЙ КОНЬ» COVER: “WAR HORSE” BY MARIANNE ELLIOT/TOM MORRIS. КОРОЛЕВСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ТЕАТРА ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ, ROYAL NATIONAL THEATRE ПОСТАНОВКА: МЭРИЭНН ЭЛЛИОТТ И ТОМ МОРРИС OF GREAT BRITAIN ФОТО: BRINKHOFF/MOEGENBURG PHOTO BY BRINKHOFF/MOEGENBURG ФОТОГРАФИИ ПРЕДОСТАВЛЕНЫ ОТДЕЛОМ ПО СВЯЗЯМ С PHOTOS ARE PROVIDED BY PR DEPARTMENT ОБЩЕСТВЕННОСТЬЮ И РЕКЛАМЕ ВСЕРОССИЙСКОГО МУЗЕЙНОГО OF MUSEUM ASSOCIATION OF MUSICAL CULTURE NAMED ОБЪЕДИНЕНИЯ МУЗЫКАЛЬНОЙ КУЛЬТУРЫ ИМ. М. И. ГЛИНКИ, AFTER M. GLINKA, PRESS SERVICES OF THE PETR FOMENKO ПРЕСС-СЛУЖБАМИ ТЕАТРА «МАСТЕРСКАЯ ПЕТРА ФОМЕНКО», WORKSHOP AND CHEKHOV INTERNATIONAL THEATRE FESTIVAL, МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ТЕАТРАЛЬНОГО ФЕСТИВАЛЯ ИМ. А. П. ЧЕХОВА, CHRISTOPHE RAYNAUD DE LAGE, OLEG CHERNOUS, CHRISTOPHE RAYNAUD DE LAGE, ОЛЕГОМ ЧЕРНОУСОМ, MARINA MARINA BALYSH, ALEXANDER IVANISHIN, BALYSH, АЛЕКСАНДРОМ ИВАНИШИНЫМ, MANIA ZYZAK MANIA ZYZAK DITOR IN HIEF LFIRA ГЛАВНЫЙ РЕДАКТОР: АЛЬФИРА АРСЛАНОВА E - -C : A ARSLANOVA DITOR IN HIEF EPUTY LGA ЗАМ. -

FOREWORD. What Thomas Hobbes Knows About Today's Russia

FOREWORD What Thomas Hobbes Knows About Today’s Russia RICHARD SCHECHNER hen I was growing up in the theater more than a half- W century ago, it was all Russia. Yes, we knew about Brecht, barely, and the drama—plays—was Ameri- can and international; but the theater, that was Russian. Not purely Russian, but doubly filtered. Stanislavski was with us in translation, first My Life in Art and then An Actor Prepares. But more impor- tant, Stanislavski’s deputies controlled the “serious” American the- ater (not the commercial side of Broadway). The Group Theatre people were vitally working—Harold Clurman, Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, Sandford Meisner. And before that, in 1923, defectors from the Moscow Art Theater/USSR, Maria Ouspenskaya and Richard Boleslavsky, started the American Laboratory Theatre, bringing to the New World what they knew of Stanislavski, firsthand. The impact of Stanislavski then—and even now—cannot be overesti- mated, in the theater and then in the movies and on to television. A kind of realism, softened to be sure (as you will see when you read the book in your hands), but pedestrian enough in the way viii \ Foreword that postmodern dance featured the way “people really moved.” The American Lab and the Group Theatre featured not so much behav- ior, the outside, but the inside—the way “people really felt.” At least that was the guiding principle. And then came Lee Strasberg, another Group Theatre alumnus, who thought he knew Stanislavski better than the master knew himself. And maybe Strasberg was right. He took Stanislavski’s relatively early way of working by means of “affective/emotional memory” and developed it into The Method—mining the “real emotions” of actors and inserting these emotions into the onstage life of the characters. -

Beyond Realism: Into the Studio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons Beyond Realism: Into the Studio Tom Cornford Shakespeare Bulletin, Volume 31, Number 4, Winter 2013, pp. 709-718 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/shb/summary/v031/31.4.cornford.html Access provided by University of York (10 Dec 2013 06:02 GMT) Epilogue Beyond Realism: Into the Studio TOM CORNFORD University of York As a director, a teacher of actors and directors, and––most of all––as an audience member, I am often confounded by the ubiquity of realist aesthetics in the Anglophone theater. The original political force of the idea of showing life-as-it-is-lived has long since drained away, and we have somehow become trapped within its husk.1 On the other hand, as a scholar of theater practice (and as a theater maker whose practice has been profoundly altered by that scholarship), I cannot help but be aware that the discipline in which I work owes a great debt to realism. That obligation is part of a still-greater debt to the Russian actor, director, and teacher Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky, whose “system” is gener- ally acknowledged to be the first comprehensive attempt to extend the widespread understanding of the art of acting and our capacity to teach and explore it further. In these concluding thoughts to this issue, I will explore the roots of Stanislavsky’s “system” in his enduring commitment to the Studio as the creative center of theater making. -

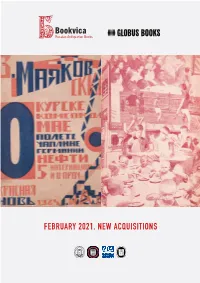

February 2021. New Acquisitions F O R E W O R D

FEBRUARY 2021. NEW ACQUISITIONS F O R E W O R D Dear friends & colleagues, We are happy to present our first catalogue of the year in which we continue to study Russian and Soviet reality through books, magazines and other printed materials. Here is a list of contents for your easier navigation: ● Architecture, p. 4 ● Women Studies, p. 19 ● Health Care, p. 25 ● Music, p. 34 ● Theatre, p. 40 ● Mayakovsky, p. 49 ● Ukraine, p. 56 ● Poetry, p. 62 ● Arctic & Antarctic, p. 66 ● Children, p. 73 ● Miscellaneous, p. 77 We will be virtually exhibiting at Firsts Canada, February 5-7 (www.firstscanada.com), andCalifornia Virtual Book Fair, March 4-6 (www.cabookfair.com). Please join us and other booksellers from all over the world! Stay well and safe, Bookvica team February 2021 BOOKVICA 2 Bookvica 15 Uznadze St. 25 Sadovnicheskaya St. 0102 Tbilisi Moscow, RUSSIA GEORGIA +7 (916) 850-6497 +7 (985) 218-6937 [email protected] www.bookvica.com Globus Books 332 Balboa St. San Francisco, CA 94118 USA +1 (415) 668-4723 [email protected] www.globusbooks.com BOOKVICA 3 I ARCHITECTURE 01 [HOUSES FOR THE PROLETARIAT] Barkhin, G. Sovremennye rabochie zhilishcha : Materialy dlia proektirovaniia i planovykh predpolozhenii po stroitel’stvu zhilishch dlia rabochikh [i.e. Contemporary Workers’ Dwellings: Materials for Projecting and Planned Suggestions for Building Dwellers for Workers]. Moscow: Voprosy truda, 1925. 80 pp., 1 folding table. 23x15,5 cm. In original constructivist wrappers with monograph MB. Restored, pale stamps of pre-war Worldcat shows no Ukrainian construction organization on the title page, pp. 13, 45, 55, 69, copies in the USA.