Acting: the First Six Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

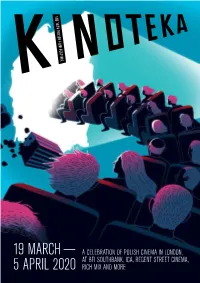

Kinoteka2020 Guide-Compressed.Pdf

Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 kinoteka.org.u k Welcome to Kinoteka 18! Welcome to Kinoteka 18! 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO KINOTEKA 18! Welcome to KINOTEKA 18! ................................................................ 1 As we enter a new decade, Polish film documentaries with a trio of recent films, continues to go from strength to strength. spanning topics such as loneliness, Japanese While Agnieszka Holland, that tireless voice students’ struggles with learning the Polish SCREENINGS & EVENTS from the old guard of Polish film-making, language, and romantic intimacy among the Opening Night Gala ....................................................................... 4 continues to channel her vision with Mr. tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto. New Polish Cinema ........................................................................ 6 Jones, a number of newer talents have broken We continue to bring you the best in through – most notably, screenwriter Mateusz exclusive cinematic experiences with a Documentaries ............................................................................ 12 Pacewicz and actor Bartosz Bielenia in Corpus series of interactive events and showcases Focus: Richard Boleslawski ............................................................... 16 Christi, Poland’s short-listed entry for this encompassing the breadth of cinema history. Family Event .............................................................................. 18 year’s Academy Awards. At the 18th Kinoteka The Cinema Museum focuses on the early Tadeusz Kantor -

The Vocabulary of Acting: a Study of the Stanislavski 'System' in Modern

THE VOCABULARY OF ACTING: A STUDY OF THE STANISLAVSKI ‘SYSTEM’ IN MODERN PRACTICE by TIMOTHY JULES KERBER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS BY RESEARCH Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis aims to examine the extent to which the vocabulary of acting created by Konstantin Stanislavski is recognized in contemporary American practice as well as the associations with the Stanislavski ‘system’ held by modern actors in the United States. During the research, a two-part survey was conducted examining the actor’s processes while creating a role for the stage and their exposure to Stanislavski and his written works. A comparison of the data explores the contemporary American understanding of the elements of the ‘system’ as well as the disconnect between the use of these elements and the stigmas attached to Stanislavski or his ‘system’ in light of misconceptions or prejudices toward either. Keywords: Stanislavski, ‘system’, actor training, United States Experienced people understood that I was only advancing a theory which the actor was to turn into second nature through long hard work and constant struggle and find a way to put it into practice. -

FOREWORD. What Thomas Hobbes Knows About Today's Russia

FOREWORD What Thomas Hobbes Knows About Today’s Russia RICHARD SCHECHNER hen I was growing up in the theater more than a half- W century ago, it was all Russia. Yes, we knew about Brecht, barely, and the drama—plays—was Ameri- can and international; but the theater, that was Russian. Not purely Russian, but doubly filtered. Stanislavski was with us in translation, first My Life in Art and then An Actor Prepares. But more impor- tant, Stanislavski’s deputies controlled the “serious” American the- ater (not the commercial side of Broadway). The Group Theatre people were vitally working—Harold Clurman, Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, Sandford Meisner. And before that, in 1923, defectors from the Moscow Art Theater/USSR, Maria Ouspenskaya and Richard Boleslavsky, started the American Laboratory Theatre, bringing to the New World what they knew of Stanislavski, firsthand. The impact of Stanislavski then—and even now—cannot be overesti- mated, in the theater and then in the movies and on to television. A kind of realism, softened to be sure (as you will see when you read the book in your hands), but pedestrian enough in the way viii \ Foreword that postmodern dance featured the way “people really moved.” The American Lab and the Group Theatre featured not so much behav- ior, the outside, but the inside—the way “people really felt.” At least that was the guiding principle. And then came Lee Strasberg, another Group Theatre alumnus, who thought he knew Stanislavski better than the master knew himself. And maybe Strasberg was right. He took Stanislavski’s relatively early way of working by means of “affective/emotional memory” and developed it into The Method—mining the “real emotions” of actors and inserting these emotions into the onstage life of the characters. -

Stage Actors and Modern Acting Methods Move to Hollywood in the 1930S

Document generated on 10/02/2021 5:28 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies Stage Actors and Modern Acting Methods Move to Hollywood in the 1930s L’arrivée à Hollywood, dans les années 1930, des acteurs de théâtre et des techniques de jeu modernes Cynthia Baron L’acteur entre les arts et les médias Article abstract Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2014 In this article, the author considers factors in commercial 1930s American theatre and film which led to the unusual circumstance of many stage-trained URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1030232ar actors employing ostensibly theatrical acting methods to respond effectively to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1030232ar the challenges and opportunities of industrial sound film production. The author proposes that with American sound cinema fundamentally changing See table of contents employment prospects on Broadway and Hollywood production practices, the 1930s represent a unique moment in the history of American performing arts, wherein stage-trained actors in New York and Hollywood developed performances according to principles of modern acting articulated by Publisher(s) Stanislavsky, the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York and the Cinémas acting manuals written by theatre-trained professionals and used by both stage and screen actors. To illustrate certain aspects of the era’s conception of modern acting, the author analyzes a scene from Captains Courageous (Victor ISSN Flemining, 1937) with Spencer Tracy and a scene from The Guardsman (Sidney 1181-6945 (print) Franklin, 1931) with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Baron, C. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College The

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By ANDREA V. JOHNSON Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE ACTING SYSTEM OF KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI AS APPLIED TO PIANO PERFORMANCE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Barbara Fast, Chair Dr. Jane Magrath, Co-Chair Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Igor Lipinski Dr. Rockey Robbins Dr. Click here to enter text. © Copyright by ANDREA V. JOHNSON 2019 All Rights Reserved. AKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this document and degree would have been impossible without the guidance and support of my community. Foremost, I wish to express my gratitude to my academic committee including current and past members: Dr. Jane Magrath, Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Eugene Enrico, Dr. Igor Lipinski, Dr. Caleb Fulton, and Dr. Rockey Robbins. Dr. Magrath, thank you for your impeccable advice, vision, planning, and unwavering dedication to my development as a pianist and teacher. You left no stone unturned to ensure that I had the support necessary for success at OU and I remain forever grateful to you for your efforts, your kindness, and your commitment to excellence. My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Fast for serving as chair of this committee, for your support throughout the degree program, and for many conversations with valuable recommendations for my professional development. Dr. Enrico, thank you for your willingness to serve on my committee and for your suggestions for the improvement of this document. -

The Chicano Theatre Movement and Actor Training in the United States

FROM LA CARPA TO THE CLASSROOM: THE CHICANO THEATRE MOVEMENT AND ACTOR TRAINING IN THE UNITED STATES Dennis Sloan A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Tim Brackenbury Graduate Faculty Representative Angela K. Ahlgren Cynthia Baron © 2020 Dennis Sloan All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor The historical narrative of actor training has thus far been limited to the history of Eurocentric actor training. Put another way, it has been predominantly white. While the history of actor training has been understudied in general, the history of training for actors of color has been almost non-existent. Yet scholars including Alison Hodge and Mark Evans have made direct links between actor training and both the evolution of theatre and the development of personal, artistic, and socio-political worldviews. Since the recorded history of actor training focuses almost exclusively on white practitioners, however, this history privileges the experiences and perspectives of white practitioners over those of color. Rooted in the argument that a history of actor training based so exclusively on whiteness is incomplete and inaccurate, this dissertation explores the history of actor training for Latinx actors, especially those who participated in and came out of the Chicanx Theatre Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and who went on to engage in other training programs afterwards. Relying primarily on original archival research, I document multifaceted attempts to train Latinx actors in the United States in the mid- to late twentieth century. -

Theatre, Jazz, and the Making of the Making of and Jazz, Theatre, Highbrow/Lowdown: Class

Books Highbrow/Lowdown: Theatre, Jazz, and the Making of the New Middle Class. By David Savran. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009; 326 pp.; illustrations. $24.95 paper. The cover image of Highbrow/Lowdown, David Savran’s study of the political economy of performing arts in the 1920s, enacts the rever- sals and defamiliarizations that the book accomplishes throughout its pages. Divided in half, the top portion is a photo of a production of Elmer Rice’s drama The Adding Machine (1923), the bottom, an image from J. Hartley Manners’s lesser-known The National Anthem (1922). The upper scene is spare and expressionistic, with an angular court- room and masked judge weighing the verdict on Rice’s Mr. Zero. The lower scene features a young Laurette Taylor surrounded by a five- piece jazz band in a basement dive. A quick glance might take these images as iconographic of the high and low that the title evokes: seri- ous literary drama on top and jazzy melodrama on bottom. By the end of the book, however, these two scenes reveal themselves not to be irreparably split by the divisions of cultural distinction but rather as two sides of the same coin. Savran reframes these plays by showing how they both sought to distance themselves from the popularity of jazz. Neither high nor low, The Adding Machine and The National Anthem together represent a middlebrow theatre, one that excised the improvisations of both jazz and popular amusements and that spoke to the social experiences of an emergent US middle class. Highbrow/Lowdown investigates the social and economic forces that underwrote the uneasy and anxious differentiation of “legitimate” American theatre from a range of amusements deemed lower class, unscripted, popular, commercial, and “illegitimate.” The book poses the following question: “Why was the Jazz Age the era in which American drama was invented?” (39). -

Utilizing the Stanislavski System and Core Acting Skills to Teach Actors in Arts Entrepreneurship Courses

Volume 2, Issue 1 ISSN: 2693-7271 Utilizing the Stanislavski System and Core Acting Skills to Teach Actors in Arts Entrepreneurship Courses James D. Hart Southern Methodist University Abstract With insight into key pedagogical approaches of theatre training, an understanding of research regarding common psychological characteristics of actors and awareness of identified parallels between arts entrepreneurship and acting course content, arts entrepreneurship instructors can, in their classrooms, increase the likelihood of relating to acting students and subsequently, leverage their students’ inherent and developed skills. Research-based psychological characteristics of actors are offered, as are suggestions to appeal to actors’ general sensibilities (and how they may wish to be engaged). The Stanislavski System is the most popular approach to actor training; its critical structural components are discussed in addition to various offshoots of the original technique. Unique features of acting training such as encouraging imagination, reflection, openness to experience, emotional connections, pursuit of goals and the importance of soft skills are emphasized. SECTION I Know Before Whom You Speak We in the theatre have our own lexicon, our actors’ jargon which has been wrought out of life. We do use, to be sure, certain scientific terms too, as for example ’the subconscious,’ ’intuition,’ but we take them in their 1 everyday, simplest connotation and not in any philosophical sense. Though there is little consensus in the literature, a number of researchers have identified common personality features of actors. Extraverted, lively and expressive, actors are generally more open to experiences than non-actors and are also believed to be more 1 Constantin Stanislavski, Stanislavski’s Legacy (London: Routledge, 2015), 30. -

History of Method Acting | Strasberg | Group Theatre | Actor Studio| the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute

1/2/14 History of Method Acting | Strasberg | Group Theatre | Actor Studio| The Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute About » Programs » Classes » Admissions » Productions and Events History The Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute is built on a history that stretches back to the 1920’s, decades before it was officially founded in 1969. In 1923, Lee Strasberg, then a young actor just beginning to find his way in what was quickly emerging as a new American theatre culture, sat in the audience for the performances of Konstantin Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) during its legendary American tour. For the first time, the American theatre witnessed the extraordinary artistic possibilities of ensemble theatre as effortlessly realized by these Russian masters. When the MAT’s American tour finished a year and half later the American theatre would never be the same. For Lee Strasberg – who would soon become one of the theatre’s most influential voices – Stanislavsky’s example inspired his “life in art”. The insights and information Strasberg gained from Stanislavsky’s MAT guided him as he contributed his own insights to the development of the actor and the American Theatre—taking Stanislavsky’s “system” and building what would eventually be called “The Method.” In time, Lee Strasberg’s work would travel the world and revolutionize acting and directing for both stage and film. In 1925, the growing influence of Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre on Lee Strasberg’s thought brought him to the doors of the recently opened American Laboratory Theatre. The “Lab”, as it was affectionately called, was founded by Maria Ouspenskaya and Richard Boleslavsky, two former actors of the Moscow Art Theatre and (more importantly) founding members of the Moscow Art Theatre’s First Studio (heavily rooted in Stanislasvky’s ‘System’. -

The Russian Pre-Theatrical Actor and the Stanislavsky System

The Russian Pre-Theatrical Actor and the Stanislavsky System by John Wesley Hill A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Theater and Drama) In The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Mbala D. Nkanga, Chair Professor Valerie Ann Kivelson Professor Leigh A. Woods Lecturer Martin W. Walsh In some cases, a children’s game, a folk game, or a village dance brings us closer to answering to the question of what is theater and what it should be than the work of a great playwright. A.I Beletskii Copyright John Wesley Hill 2009 To Leta, Lydia, and Vladimir ii Acknowledgements Thanks to: Center for Russian and East European Studies at the University of Michigan, Lauren Atkins, Wojciech Beltkiewicz, Myra Bertrand, Jeffrey Blim, John Carnwath, Stratos Constantinidis, Janet Crayne, Kate Elswit, Jody Enders, Rachel Facey, Karen Frye, Jay M. Gipson-King, Maurice and Barbara Hill, Olga P. Ignateyva, Claudia Jensen, Mary-Allen Johnson, Valerie Kivelson, Boris Katz, Bonnie Kerschbaum, Sam Kinser, Natalie Kononenko, Ann Kushkova, Alaina Lemon, Irina Lewandowski , M.A. Lobanov, Ewa Małachowska-Pasek, Holly Maples, Rosalind Martin, Predrag Matejic, Pat McCune, Anna Meerman-Bader, Vitalii Mikhailovich Miller, A.F. Nekrylova, Mbala Nkanga, Linda Norton, D Ohlandt (Ross), Ingrid Peterson, Irakli Pipia, Greg Poggi, Henry Reynolds, Talia Rodgers, Svitlana Rogovyk, Jeanmarie Rouhier-Willoughby, Suleyman Sarihan, Becky Seauvageau, Eric Schinzer, I.I. Shangina, Mila Shevchenko, Stephen Siercks, Daniel Strauss, Hellen Sullivan, Maeve Sullivan, Marina Swoboda, A.L. Toporkov, Igor’ Ushakov, Bisera Vlahovljak, Martin Walsh, EJ Westlake, Erica Wetter, Steven Whiting, Faith Wigzell, Leigh Woods, and the staff of Interlibrary Loan at the University of Michigan.