Film for Thought – Nazarin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Series 29:6) Luis Buñuel, VIRIDIANA (1961, 90 Min)

September 30, 2014 (Series 29:6) Luis Buñuel, VIRIDIANA (1961, 90 min) Directed by Luis Buñuel Written by Julio Alejandro, Luis Buñuel, and Benito Pérez Galdós (novel “Halma”) Cinematography by José F. Aguayo Produced by Gustavo Alatriste Music by Gustavo Pittaluga Film Editing by Pedro del Rey Set Decoration by Francisco Canet Silvia Pinal ... Viridiana Francisco Rabal ... Jorge Fernando Rey ... Don Jaime José Calvo ... Don Amalio Margarita Lozano ... Ramona José Manuel Martín ... El Cojo Victoria Zinny ... Lucia Luis Heredia ... Manuel 'El Poca' Joaquín Roa ... Señor Zequiel Lola Gaos ... Enedina María Isbert ... Beggar Teresa Rabal ... Rita Julio Alejandro (writer) (b. 1906 in Huesca, Arágon, Spain—d. 1995 (age 89) in Javea, Valencia, Spain) wrote 84 films and television shows, among them 1984 “Tú eres mi destino” (TV Luis Buñuel (director) Series), 1976 Man on the Bridge, 1974 Bárbara, 1971 Yesenia, (b. Luis Buñuel Portolés, February 22, 1900 in Calanda, Aragon, 1971 El ídolo, 1970 Tristana, 1969 Memories of the Future, Spain—d. July 29, 1983 (age 83) in Mexico City, Distrito 1965 Simon of the Desert, 1962 A Mother's Sin, 1961 Viridiana, Federal, Mexico) directed 34 films, which are 1977 That 1959 Nazarin, 1955 After the Storm, and 1951 Mujeres sin Obscure Object of Desire, 1974 The Phantom of Liberty, 1972 mañana. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1970 Tristana, 1969 The Milky Way, 1967 Belle de Jour, 1965 Simon of the Desert, 1964 José F. Aguayo (cinematographer) (b. José Fernández Aguayo, Diary of a Chambermaid, 1962 The Exterminating -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Exterminating Angel

6 FEBRUARY 2001 (III:4) LUIS BUÑUEL (Luis Buñuel Portolés, 22 February 1900, Calanda, Spain—29 July 1983, Mexico City, Mexico,cirrhosis of the liver) became a controversial and internationally-known filmmaker with his first film, the 17-minute Un Chien andalou 1929 (An Andalousian Dog), which he made with Salvador Dali. He wrote and directed 33 other films, most of them interesting, man y of them considered master pieces by critics and by fellow filmmaker s. Some of them are : Cet obscur objet du désir 1977 (That Obscure Object of Desire), Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie 1972 (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), Tristana 1970, La Voie lactée 1969 (The Milky Way), Belle de jour 1967, Simón del desierto 1965 (Simon of the Desert), Viridiana 1961, Nazarín 1958, Subida al cielo 1952 (Ascent to Heaven, Mexican Bus Ride), Los Olvidados 1950 (The Young and the Damned), Las Hurdes 1932 (Land Without Bread ), and L’Âge d'or 1930 (Age of Gold). His autobiography, My Last Sigh (Vintage, New York) was published the year after his death. Some critics say much of it is apocryphal, the screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (who collaborated with Buñuel on six scripts), claims he wrote it based on things Buñel said. Whatever: it’s a terrific book. Leonard Maltin wrote this biographical note on Buñuel in his Movie Encyclopedia (1994): “One of the screen's greatest artists, a director whose unerring society-with remarkable energy and little mercy: The instincts and assured grasp of cinematic technique enabled Exterminating Angel (1962), a savage him to create some of film's most memorable images....After assault on the bourgeois mentality, with guests trapped at a the sardoni c docum entary Las Hurdes in 1932, Buñuel took a dinner party; Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), a costume 15-year layoff from directing. -

Buñuel and Mexico: the Crisis of National Cinema

UC_Acevedo-Muæoz (D).qxd 8/25/2003 1:12 PM Page i Buñuel and Mexico This page intentionally left blank UC_Acevedo-Muæoz (D).qxd 8/25/2003 1:12 PM Page iii Buñuel and Mexico The Crisis of National Cinema Ernesto R. Acevedo-Muñoz University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London UC_Acevedo-Muæoz (D).qxd 8/25/2003 1:12 PM Page iv University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2003 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Acevedo-Muñoz, Ernesto R., 1968–. Buñuel and Mexico : the crisis of national cinema / by Ernesto R. Acevedo-Muñoz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–520-23952-0 (alk. paper) 1. Buñuel, Luis, 1900– .—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Motion pictures—Mexico. I. Title. PN1998.3.B86A64 2003 791.43'0233'092—dc21 2003044766 Manufactured in the United States of America 1211 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 10987654321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine- free (TCF). It meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48– 1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). 8 UC_Acevedo-Muæoz (D).qxd 8/25/2003 1:12 PM Page v A Mamá, Papá, y Carlos R. Por quererme y apoyarme sin pedir nada a cambio, y por siempre ir conmigo al cine And in loving memory of Stan Brakhage (1933–2003) This page intentionally left blank UC_Acevedo-Muæoz (D).qxd 8/25/2003 1:12 PM Page vii Contents List of Figures ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. -

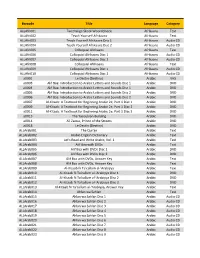

Barcode Title Language Category Allafri001 Tweetalige Skool

Barcode Title Language Category ALLAfri001 Tweetalige Skool-Woordeboek Afrikaans Text ALLAfri002 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri003 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri004 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri005 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri006 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri007 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri008 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri009 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri010 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD a0001 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic VHS a0003 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0004 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0005 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0006 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0007 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0009 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0011 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 3 Arabic DVD a0013 The Yacoubian Building Arabic DVD a0014 Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets Arabic DVD a0018 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic DVD ALLArab001 The Qur'an Arabic Text ALLArab002 Arabic-English Dictionary Arabic Text ALLArab003 Let's Read and Write Arabic, Vol. 1 Arabic Text ALLArab004 Alif Baa with DVDs Arabic Text ALLArab005 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 1 Arabic DVD ALLArab006 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 2 Arabic -

Filmmaking and Film Studies

Libraries FILMMAKING AND FILM STUDIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 025 Sunset Red DVD-9505 African Violet #1 VHS-3655 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 After Gorbachev's USSR DVD-2615 11 x 14/One Way Boogie Woogie/27 Years Later DVD-9953 Agit-Film VHS-2622 13 Most Beautiful: Songs for Andy Warhol's Screen Tests DVD-2978 Ah, Liberty! VHS-5952 14 Video Paintings DVD-8355 Airport/Airport 1975 DVD-3307 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-1239 Akira DVD-0315 DVD-0260 DVD-1214 25th Hour DVD-2291 Akran DVD-6838 39 Steps DVD-0337 Alaya VHS-1199 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Alexander Nevsky DVD-8367 400 Blows DVD-8362 DVD-4983 56 Up DVD-8322 Alexander Nevsky (Criterion) c.2 DVD-4983 c.2 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 Alexeieff at the Pinboard VHS-3822 A to Z VHS-4494 Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection Bonus DVD-0958 Disc Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 1-4) DVD-6979 Discs 1 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 5-8) DVD-6979 Discs 5 Alice DVD-4863 Abbas Kiarostami (Discs 9-10) DVD-6979 Discs 9 Alice c,2 DVD-4863 c.2 Aberration of Light DVD-7584 All My Life VHS-2415 Abstronic VHS-1350 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD-1284 Ace of Light VHS-1123 All that Heaven Allows DVD-0329 Across the Rappahannock VHS-5541 All That Heaven Allows c.2 DVD-0329 c.2 Act of Killing DVD-4434 Alleessi: An African Actress DVD-3247 Adaptation DVD-4192 Alphaville -

An Approach to Cinema Novo Through 'La Ricotta'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Pasolini and Third World hunger: an approach to Cinema Novo through ©La ricotta© Article Accepted Version Elduque, A. (2016) Pasolini and Third World hunger: an approach to Cinema Novo through ©La ricotta©. Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 4 (3). pp. 369-385. ISSN 20477368 doi: https://doi.org/10.1386/jicms.4.3.335_7 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/65671/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher's version if you intend to cite from the work. Published version at: http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals/view-Journal,id=215/ To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jicms.4.3.335_7 Publisher: Intellect All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading's research outputs online Pasolini and Third World hunger: an approach to Cinema Novo through La ricotta Among the numerous connections that exist between Latin American and Italian cinema, the link between Pasolini’s works and Brazilian films is one of the most evident and frequently analysed. This relation is so fruitful that, although it has been the focus of a huge number of works, it remains an endless source for cultural and formal analysis. -

Thomas Adès's the Exterminating Angel

TEMPO 71 (280) 21–46 © 2017 Cambridge University Press 21 doi:10.1017/S0040298217000067 THOMAS ADÈS’S THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL Edward Venn Abstract: Thomas Adès’s third opera, The Exterminating Angel, is based closely upon Luis Buñuel’s 1962 film El ángel exterminador, in which the hosts and guests at a high-society dinner party find themselves inexplicably unable to leave the dining room. Initial critical response to the opera too often focused on superficial simi- larities and discrepancies between the two works at the expense of attending to the specifically musical ways in which Adès presented the drama. This article explores the role that repetition plays in the opera, and in particular how repetitions serve both as a means of critiquing bourgeois sensibilities and as a representation of (loss of) will. I conclude by drawing on the work of Deleuze in order to situate the climax of the opera against the notion of the eternal return, highlighting how the music articulates the dramatic failure of the characters to escape. Thomas Adès’s third opera, The Exterminating Angel, is based closely upon Luis Buñuel’s 1962 film El ángel exterminador, in which the hosts and guests at a high-society dinner party find themselves inex- plicably unable to leave the dining room. Having first seen the film as a teenager, Adès was attracted to its operatic potential, ‘because every opera is about getting out of a particular situation’.1 Copyright issues prevented an early realisation of these intentions;2 but although these were not fully resolved until 2011,3 work with Tom Cairns on the libretto began in 2009.4 The opera’s commission was formally announced in November 2011,5 and the final versions of the score and libretto are dated 2015. -

ASFS-AFHVS 2009 Program Penn State College

JOINT ANNUAL MEETING OF AFHVS & ASFS MAY 28‐31, 2009 PENN STATER CONFERENCE CENTER STATE COLLEGE, PENNSYLVANIA, USA 1 2 2009 AFHVS/ASFS Conference Informing Possibilities for the Future of Food and Agriculture WELCOME! Welcome to the 2009 joint annual meeting of the Agriculture, Food and Human Values Society and the Association for the Study of Food and Society! The theme of our conference this year—“Informing Possibilities for the Future of Food and Agriculture”—has only become more relevant since it was first settled upon about a year ago. As the administrations of national governments have changed, as economies at a multitude of scales experience strains and generate hardships not seen in decades, as more people actively recognize and respond to the social and environmental crises that cross‐cut our local places and global relations in the 21st century, we need to come together, now perhaps more than ever, to share our research findings, our intellectual insights and our practical ideas about the future of food and agriculture. This is precisely what will happen in dizzying abundance over the two‐and‐a‐half days of the 2009 AFHVS/ASFS conference. We hope you enjoy the conference. We welcome you to Penn State University, to the borough of State College, and to the beautiful wooded hills and farms of Central Pennsylvania! We encourage you to take a walking tour of at least some of the 7,200 acre campus with over 14,064 trees including 224 historic stately elm trees. The pedestrian‐friendly campus is beautifully landscaped with perennial flowers, shrubs, and trees and the spring is an excellent time to take in the sights. -

Floresta De Signos

Doc’s Kingdom 2019 Floresta de signos ~ Forest of signs Arcos de Valdevez 1 - 6 de Setembro de 2019 1 Com a cabeça nas estrelas, envoltas em tecidos estampados coloridos, deambulemos pelas forestas em busca de territórios imaginários. Entre o céu e a terra, luz e trevas, memória e esquecimento, que cintilem as projeções e ressoem as palavras. Vamos abrir as janelas e deixar o vento entrar. Vamos mergulhar em águas intemporais refetindo as chamas vacilantes das nossas vidas multiplicadas. Vamos desbastar, cortar, cavar, tecer, desdobrar e desenhar mapas para nos perdermos, para melhor nos encontrarmos no mundo habitável do cinema. Agnès Wildenstein, programadora convidada ~ Te head in the stars, draped in colorful patterned fabrics, let us wander in the forests in search of imagined territories. Between sky and earth, light and darkness, memory and forgetfulness, may the projections sparkle and the words resound. Let’s open the windows and let in the wind. Let’s dive into timeless waters refecting the fickering fames of our multiplied lives. Let’s cut, open up, dig, weave, unfold, draw maps to get lost, in order to better fnd ourselves in the habitable world of cinema. Agnès Wildenstein, guest programmer 2 3 Índice according to the present 11 after emigrating 15 animism 25 apprendre 26 archéologie, ça fait penser 27 at the instigation 28 both sides 35 but what a spiral 36 can we feel 38 carnet du bois 48 ce que j’aime 51 cena 16 52 ces mots 53 chamar 54 cher robert 56 chinawaren 57 classification of embroidery 58 color is something 63