Di Zi Gui � (Students' Rules)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imprints FINAL 15Dec2016.Indd

ls ia er at M ed ht ig yr op C : ss re P ity rs ve ni U se Newest Sources of Western Zhou History: ne hi Inscribed Bronze Vessels, 2000–2010 C he T Edward L. SHAUGHNESSY The University of Chicago In 2002, I published a survey of inscribed bronze vessels of the Western Zhou period that had appeared in the course of the preceding decade. timing was appropriate for at least a couple of reasons. First, the 1990s marked the first flowering of the new Chinese economic expansion; with the dramatic increase in construction activity and with newfound wealth in China came a concomitant rise in the number of ancient bronze vessels taken out of China’s earth. Although much of this excavation was unfor- tunately undertaken by tomb robbers, and the individual bronzes thus lost their archaeological context, nevertheless many of them appeared on the antiques markets and eventually made their way into museums and/or the scholarly press. Second, the decade also witnessed the five-year long Xia- Shang-Zhou Chronology Project (1995–2000). This multidisciplinary inquiry into ancient China’s political chronology was funded by the Chinese government at levels hitherto unimagined for humanistic and social science research, and it resulted in numerous discoveries and publi- cations. The chronology of the Western Zhou period, based to a very large extent on the inscriptions in bronze vessels of the period, was perhaps the most important topic explored by this project. The decade witnessed extensive archaeological excavations at several major Zhou states, as well as the discovery of several fully-dated bronze inscriptions that were the subject of much discussion in the context of the “Xia-Shang-Zhou Chro- nology Project.” 1 The sive archaeologicalThe ten years campaigns, that have severaljust passed of them have unearthing brought several sites and more ceme- exten- teries of heretofore unknown states within the Zhou realm, as well as many, many more bronze vessels from throughout the Western Zhou period, some of them with truly 2startling inscriptions. -

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

Chen Gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian

chen gui denis twitchett Chen gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian ome quarter-century ago, studies by Antonino Forte and Richard S Guisso greatly advanced our understanding of the ways in which the empress Wu Zetian ࣳঞ֚ made deliberate and sophisticated use of Buddhist materials both before and after declaring herself ruler of a new Zhou ࡌʳdynasty in 690, in particular the text of Dayun jing Օႆᆖ in establishing her claim to be a legitimate sovereign.1 However, little attention has ever been given to the numerous political writings that had earlier been compiled in her name. These show that for some years before the demise of her husband emperor Gaozong in 683, she had been at considerable pains to establish her credentials as a potential ruler in more conventional terms, and had commissioned the writing of a large series of political writings designed to provide the ideologi- cal basis for both a new style of “Confucian” imperial rule and a new type of minister. All save two of these works were long ago lost in China, where none of her writings seems to have survived the Song, and most may not have survived the Tang. We are fortunate enough to possess that titled complete with its commentary, and also a fragmentary Chen gui copy of the work on music commissioned in her name, Yue shu yaolu ᑗ ᙕ,2 only thanks to their preservation in Japan. They had been ac- quired by an embassy to China, almost certainly that of 702–704, led టԳ (see the concluding section of thisضby Awata no ason Mahito ொ article) to the court of empress Wu, who was at that time sovereign of 1 See Antonino Forte, Political Propaganda and Ideology in China at the End of the Seventh Century (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale,1976); R. -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

CEPS: an Open Access MATLAB Graphical User Interface (GUI) for the Analysis of Complexity and Entropy in Physiological Signals

entropy Article CEPS: An Open Access MATLAB Graphical User Interface (GUI) for the Analysis of Complexity and Entropy in Physiological Signals David Mayor 1,* , Deepak Panday 2, Hari Kala Kandel 3, Tony Steffert 4,5 and Duncan Banks 5 1 School of Health and Social Work, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield AL10 9AB, UK 2 School of Engineering and Computer Science, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield AL10 9AB, UK; [email protected] 3 Department of Computing, Goldsmiths College, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK; [email protected] 4 MindSpire, Napier House, 14-16 Mount Ephraim Rd, Tunbridge Wells TN1 1EE, UK; [email protected] 5 School of Life, Health and Chemical Sciences, Walton Hall, The Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background: We developed CEPS as an open access MATLAB® GUI (graphical user interface) for the analysis of Complexity and Entropy in Physiological Signals (CEPS), and demonstrate its use with an example data set that shows the effects of paced breathing (PB) on variability of heart, pulse and respiration rates. CEPS is also sufficiently adaptable to be used for other time series physiological data such as EEG (electroencephalography), postural sway or temperature measurements. Methods: Data were collected from a convenience sample of nine healthy adults in a pilot for a larger study investigating the effects on vagal tone of breathing paced at various Citation: Mayor, D.; Panday, D.; different rates, part of a development programme for a home training stress reduction system. Results: Kandel, H.K.; Steffert, T.; Banks, D. -

T H E a Rt a N D a Rc H a E O L O Gy O F a N C I E Nt C H I

china cover_correct2pgs 7/23/04 2:15 PM Page 1 T h e A r t a n d A rc h a e o l o g y o f A n c i e nt C h i n a A T E A C H E R ’ S G U I D E The Art and Archaeology of Ancient China A T E A C H ER’S GUI DE PROJECT DIRECTOR Carson Herrington WRITER Elizabeth Benskin PROJECT ASSISTANT Kristina Giasi EDITOR Gail Spilsbury DESIGNER Kimberly Glyder ILLUSTRATOR Ranjani Venkatesh CALLIGRAPHER John Wang TEACHER CONSULTANTS Toni Conklin, Bancroft Elementary School, Washington, D.C. Ann R. Erickson, Art Resource Teacher and Curriculum Developer, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia Krista Forsgren, Director, Windows on Asia, Atlanta, Georgia Christina Hanawalt, Art Teacher, Westfield High School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia The maps on pages 4, 7, 10, 12, 16, and 18 are courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The map on page 106 is courtesy of Maps.com. Special thanks go to Jan Stuart and Joseph Chang, associate curators of Chinese art at the Freer and Sackler galleries, and to Paul Jett, the museum’s head of Conservation and Scientific Research, for their advice and assistance. Thanks also go to Michael Wilpers, Performing Arts Programmer, and to Christine Lee and Larry Hyman for their suggestions and contributions. This publication was made possible by a grant from the Freeman Foundation. The CD-ROM included with this publication was created in collaboration with Fairfax County Public Schools. It was made possible, in part, with in- kind support from Kaidan Inc. -

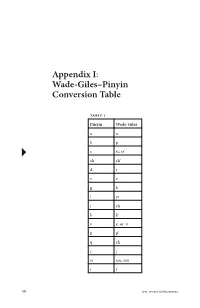

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's Name Dates R Pinyin Romanization of Artist's

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's name ❍ Dates ❍ Pinyin Romanization of Artist's name Artists are listed alphabetically by Wade-Giles. This list is not comprehensive; it reflects the catalogue of visual resource materials offered by AAPD. Searches are possible in either form of Romanization. To search for a specific artist, use the find mode (under Edit) from the pull-down menu. Lady Ai-lien ❍ (late 19th c.) ❍ Lady Ailian Cha Shih-piao ❍ (1615-1698) ❍ Zha Shibiao Chai Ta-K'un ❍ (d.1804) ❍ Zhai Dakun Chan Ching-feng ❍ (1520-1602) ❍ Zhan Jingfeng Chang Feng ❍ (active ca.1636-1662) ❍ Zhang Feng Chang Feng-i ❍ (1527-1613) ❍ Zhang Fengyi Chang Fu ❍ (1546-1631) ❍ Zhang Fu Chang Jui-t'u ❍ (1570-1641) ❍ Zhang Ruitu Chang Jo-ai ❍ (1713-1746) ❍ Zhang Ruoai Chang Jo-ch'eng ❍ (1722-1770) ❍ Zhang Ruocheng Chang Ning ❍ (1427-ca.1495) ❍ Zhang Ning Chang P'ei-tun ❍ (1772-1842) ❍ Zhang Peitun Chang Pi ❍ (1425-1487) ❍ Zhang Bi Chang Ta-ch'ien [Chang Dai-chien] ❍ (1899-1983) ❍ Zhang Daqian Chang Tao-wu ❍ (active late 18th c.) ❍ Zhang Daowu Chang Wu ❍ (active ca.1360) ❍ Zhang Wu Chang Yü [Chang T'ien-yu] ❍ (1283-1350, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu [Zhang Tianyu] Chang Yü ❍ (1333-1385, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu Chang Yu ❍ (active 15th c., Ming Dynasty) ❍ Zhang You Chang Yü-ts'ai ❍ (died 1316) ❍ Zhang Yucai Chao Chung ❍ (active 2nd half 14th c.) ❍ Zhao Zhong Chao Kuang-fu ❍ (active ca. 960-975) ❍ Zhao Guangfu Chao Ch'i ❍ (active ca.1488-1505) ❍ Zhao Qi Chao Lin ❍ (14th century) ❍ Zhao Lin Chao Ling-jang [Chao Ta-nien] ❍ (active ca. -

On the War Culture of Rewarding, Management and Sacrificing in the Ancient China Zhou Dynasty Based on the War Inscriptions

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 11, No. 8, 2015, pp. 60-66 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/7434 www.cscanada.org On the War Culture of Rewarding, Management and Sacrificing in the Ancient China Zhou Dynasty Based on the War Inscriptions DENG Fei[a],* [a]Institute of Chinese Language and Documents, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. INTRODUCTION *Corresponding author. As we know, the early Chinese considered that two things Supported by National Funds for Social Science “Research on the Time were the most important for one country. One was Category in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions in Ancient Chinese Shang sacrificing to the gods and ancestors. One was fighting. Dynasty” (13XYY017); Chinese Special Postdoctoral Funds “Research Fighting continued the political activity. The bronze on the Time Category in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions in Ancient inscriptions in the Zhou dynasty are of rich language Chinese Shang Dynasty” (2014T70841); Chinese Postdoctoral Funds materials about war, contrast to the oracle-bone “Research on the Cognitive Issues of the Time Category in the Oracle- Bone Inscriptions in Ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty” (2013M531921); inscriptions in the Shang dynasty, these language Chongqing city’s Postdoctoral Funds “ Research on the Different materials are systematical and complete, so they have Expressions of the Time Category in the Oracle-Bone Inscriptions in provided so many materials to us to investigate all aspects Ancient Chinese Shang Dynasty” (XM201359). of war culture. This paper will discuss the war culture of rewarding, management and sacrificing. Received 19 April 2015; accepted 2 June 2015 Published online 26 August 2015 1. -

Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 6 2-1-2003 Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans Sheau-yueh J. Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh J. (2003) "Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. researching YOUR ASIAN ROOTS CHINESE AMERICANS sheau yueh J chao baruch college city university new york introduction situated busiest mid town manhattan baruch senior colleges within city university new york consists twenty campuses spread five boroughs new york city intensive business curriculum attracts students country especially those asian pacific ethnic background encompasses nearly 45 entire student population baruch librarian baruch college city university new york I1 encountered various types questions serving reference desk generally these questions solved without major difficulties however beginning seven years ago unique question referred me repeatedly each new semester began how I1 find reference book trace my chinese name resource english help me find origin my chinese surname