Spaced Learning Enhances Episodic Memory by Increasing Neural Pattern Similarity Across Repetitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing Exam Prep with Customized Digital Flashcards

Enhancing Exam Prep with Customized Digital Flashcards Susan L. Murray Julie Phelps Hanan Altabbakh Missouri University of Science and Technology American University of Kuwait Abstract Flashcards are traditionally constructed with pa- Wissman, Rawson, and Pyc (2012) showed that It is common for college classes to contain basic per index cards; questions are written or typed on one students have limited knowledge of the benefit of us- information that must be mastered before learning side of an index card, and the solution is on the other. ing flashcards in their learning process. The study re- more difficult concepts or applications. Many students Digital flashcards can simulate this design. They can be vealed that 83% of students reported using flashcards struggle with learning facts, terms, or fundamental viewed at different speeds for better-spaced repetition to learn vocabulary, while 29% used them for key con- concepts; in some situations, students are even un- application. Showing the next card at the proper timing cepts. The study finds that students would significantly sure about what they should study. Flashcards are a ensure the appropriate lags between sessions or within benefit from flashcards if they extend their application well-established educational aid for learning basic the cards themselves (Pham, Chen, Nguyen, & Hwang, to a broader variety of learning objectives. The same information. Software programs are available that can 2016). There are other advantages for students using study also revealed that few instructors recommend generate flashcards electronically. This paper details an digital flashcards. They are easy to share or post online. using flashcards as a learning strategy in their courses. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

Chen Gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian

chen gui denis twitchett Chen gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian ome quarter-century ago, studies by Antonino Forte and Richard S Guisso greatly advanced our understanding of the ways in which the empress Wu Zetian ࣳঞ֚ made deliberate and sophisticated use of Buddhist materials both before and after declaring herself ruler of a new Zhou ࡌʳdynasty in 690, in particular the text of Dayun jing Օႆᆖ in establishing her claim to be a legitimate sovereign.1 However, little attention has ever been given to the numerous political writings that had earlier been compiled in her name. These show that for some years before the demise of her husband emperor Gaozong in 683, she had been at considerable pains to establish her credentials as a potential ruler in more conventional terms, and had commissioned the writing of a large series of political writings designed to provide the ideologi- cal basis for both a new style of “Confucian” imperial rule and a new type of minister. All save two of these works were long ago lost in China, where none of her writings seems to have survived the Song, and most may not have survived the Tang. We are fortunate enough to possess that titled complete with its commentary, and also a fragmentary Chen gui copy of the work on music commissioned in her name, Yue shu yaolu ᑗ ᙕ,2 only thanks to their preservation in Japan. They had been ac- quired by an embassy to China, almost certainly that of 702–704, led టԳ (see the concluding section of thisضby Awata no ason Mahito ொ article) to the court of empress Wu, who was at that time sovereign of 1 See Antonino Forte, Political Propaganda and Ideology in China at the End of the Seventh Century (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale,1976); R. -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

Investigating Distribution of Practice Effects for the Learning of Foreign Language Verb Morphology in the Young Learner Classroom

This is a repository copy of Investigating distribution of practice effects for the learning of foreign language verb morphology in the young learner classroom. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/141710/ Version: Published Version Article: Kasprowicz, Rowena Eloise orcid.org/0000-0001-9248-6834, Marsden, Emma Josephine orcid.org/0000-0003-4086-5765 and Sephton, Nick (2019) Investigating distribution of practice effects for the learning of foreign language verb morphology in the young learner classroom. The Modern Language Journal. pp. 580-606. ISSN 1540-4781 https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12586 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Investigating Distribution of Practice Effects for the Learning of Foreign Language Verb Morphology in the Young Learner Classroom ROWENA E. KASPROWICZ,1 EMMA MARSDEN,2 and NICK SEPHTON3 1University -

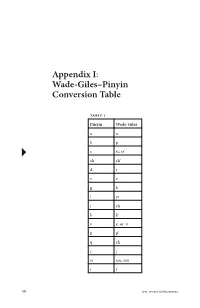

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's Name Dates R Pinyin Romanization of Artist's

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's name ❍ Dates ❍ Pinyin Romanization of Artist's name Artists are listed alphabetically by Wade-Giles. This list is not comprehensive; it reflects the catalogue of visual resource materials offered by AAPD. Searches are possible in either form of Romanization. To search for a specific artist, use the find mode (under Edit) from the pull-down menu. Lady Ai-lien ❍ (late 19th c.) ❍ Lady Ailian Cha Shih-piao ❍ (1615-1698) ❍ Zha Shibiao Chai Ta-K'un ❍ (d.1804) ❍ Zhai Dakun Chan Ching-feng ❍ (1520-1602) ❍ Zhan Jingfeng Chang Feng ❍ (active ca.1636-1662) ❍ Zhang Feng Chang Feng-i ❍ (1527-1613) ❍ Zhang Fengyi Chang Fu ❍ (1546-1631) ❍ Zhang Fu Chang Jui-t'u ❍ (1570-1641) ❍ Zhang Ruitu Chang Jo-ai ❍ (1713-1746) ❍ Zhang Ruoai Chang Jo-ch'eng ❍ (1722-1770) ❍ Zhang Ruocheng Chang Ning ❍ (1427-ca.1495) ❍ Zhang Ning Chang P'ei-tun ❍ (1772-1842) ❍ Zhang Peitun Chang Pi ❍ (1425-1487) ❍ Zhang Bi Chang Ta-ch'ien [Chang Dai-chien] ❍ (1899-1983) ❍ Zhang Daqian Chang Tao-wu ❍ (active late 18th c.) ❍ Zhang Daowu Chang Wu ❍ (active ca.1360) ❍ Zhang Wu Chang Yü [Chang T'ien-yu] ❍ (1283-1350, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu [Zhang Tianyu] Chang Yü ❍ (1333-1385, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu Chang Yu ❍ (active 15th c., Ming Dynasty) ❍ Zhang You Chang Yü-ts'ai ❍ (died 1316) ❍ Zhang Yucai Chao Chung ❍ (active 2nd half 14th c.) ❍ Zhao Zhong Chao Kuang-fu ❍ (active ca. 960-975) ❍ Zhao Guangfu Chao Ch'i ❍ (active ca.1488-1505) ❍ Zhao Qi Chao Lin ❍ (14th century) ❍ Zhao Lin Chao Ling-jang [Chao Ta-nien] ❍ (active ca. -

Implementing Distributed Practice

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Graduate Research Papers Student Work 2005 Implementing distributed practice Christi Sires University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2005 Christi Sires Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp Part of the Educational Methods Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Sires, Christi, "Implementing distributed practice" (2005). Graduate Research Papers. 1539. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/1539 This Open Access Graduate Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Research Papers by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Implementing distributed practice Abstract Distributed practice is a daily routine where students are exposed to a math problem, asked to solve it, and then explain how they solved it. The idea of short intervals of instruction over a period of time can have remarkable results. This instructional strategy has been cited in numerous research studies, an indication that it may be successful in helping students better understand how they can solve mathematical problems. This study will try to determine the growth of Jewett Elementary's first grade students as they were exposed to distributed practice over a period of time from first ot second quarter during the 2004-2005 school year. The areas that -

Distributed Practice Theoretical Analysis and Practical Implications

Optimizing Distributed Practice Theoretical Analysis and Practical Implications Nicholas J. Cepeda,1,2 Noriko Coburn,2 Doug Rohrer,3 John T. Wixted,2 Michael C. Mozer,4 and Harold Pashler2 1York University, Toronto, ON, Canada 2University of California, San Diego, CA 3University of South Florida, FL 4University of Colorado, Boulder, CO Abstract. More than a century of research shows that increasing the gap between study episodes using the same material can enhance retention, yet little is known about how this so-called distributed practice effect unfolds over nontrivial periods. In two three-session laboratory studies, we examined the effects of gap on retention of foreign vocabulary, facts, and names of visual objects, with test delays up to 6 months. An optimal gap improved final recall by up to 150%. Both studies demonstrated nonmonotonic gap effects: Increases in gap caused test accuracy to initially sharply increase and then gradually decline. These results provide new constraints on theories of spacing and confirm the importance of cumulative reviews to promote retention over meaningful time periods. Keywords: spacing effect, distributed practice, long-term memory, instructional design Introduction Distributed Practice: Basic Phenomena An increased temporal lag between study episodes often The typical distributed practice study – including the studies enhances performance on a later memory test. This finding described below – requires subjects to study the same mate- is generally referred to as the ‘‘spacing effect’’, ‘‘lag effect’’, rial in each of the two learning episodes separated by an or ‘‘distributed practice effect’’ (for reviews, see Cepeda, interstudy gap (henceforth, gap). The interval between the Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006; Dempster, 1989; second learning episode and the final test is the test delay. -

Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 6 2-1-2003 Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans Sheau-yueh J. Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh J. (2003) "Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. researching YOUR ASIAN ROOTS CHINESE AMERICANS sheau yueh J chao baruch college city university new york introduction situated busiest mid town manhattan baruch senior colleges within city university new york consists twenty campuses spread five boroughs new york city intensive business curriculum attracts students country especially those asian pacific ethnic background encompasses nearly 45 entire student population baruch librarian baruch college city university new york I1 encountered various types questions serving reference desk generally these questions solved without major difficulties however beginning seven years ago unique question referred me repeatedly each new semester began how I1 find reference book trace my chinese name resource english help me find origin my chinese surname -

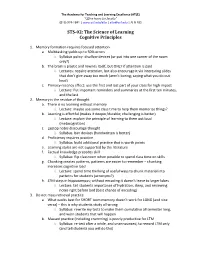

STS-‐02: the Science of Learning Cognitive Principles

The Academy for Teaching and Learning Excellence (ATLE) “Office hours for faculty” (813) 974-1841 | www.usf.edu/atle | [email protected] | ALN 185 STS-02: The Science of Learning Cognitive Principles 1. Memory formation requires focused attention a. Multitasking yields up to 50% errors i. Syllabus policy: disallow devices (or put into one corner of the room only?) b. The brain is plastic and rewires itself, but ONLY if attention is paid i. Lectures: require attention, but also encourage it via interesting slides that don’t give away too much (aren’t boring; saying what you do out loud) c. Primacy-recency effect: use the first and last part of your class for high impact i. Lecture: Put important reminders and summaries at the first ten minutes, and the last. 2. Memory is the residue of thought a. There is no learning without memory i. Lecture: maybe use some class time to help them memorize things? b. Learning is effortful (makes it deeper/durable; challenging is better) i. Lecture: explain the principle of learning to them out loud (metacognition) c. Laptop notes discourage thought i. Syllabus: ban devices (handwritten is better) d. Proficiency requires practice i. Syllabus: build additional practice that is worth points e. Learning styles are not supported by the literature f. Factual knowledge precedes skill i. Syllabus: flip classroom when possible to spend class time on skills g. Chunking creates patterns, patterns are easier to remember – chunking increases cognitive load i. Lecture: spend time thinking of useful ways to chunk material into patterns for students (acronyms?) h.