Abstract Spring, Mark Jeremy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/46p561r4 Author Murdock, Sara Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Sara Murdock 2018 © Copyright by Sara Murdock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange by Sara Murdock Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor David H. Gere, Chair This dissertation focuses on the concept of social equity in the context of performing arts-based cultural exchange. The work draws upon with Performance Studies and Cultural Studies, reviews several examples through Critical Race Studies and Memory Studies lenses, and then makes advances in Whiteness Studies. All cases revolve around the performing arts as a vehicle for bridging difference. From a practical vantage, the dissertation reviews how organizations do or do not succeed in activating their intentions in an equitable fashion. The document culminates in a Checklist for Social Good, offering a tangible way to link programmatic intentions with implementation. Fieldwork cited includes interviews, ethnographies, and participant observations to determine how programmatic design within cultural exchange has affected social narratives, such as whose cultures have value and on whose terms the programs progress. The dissertation is ii particularly concerned with the ways in which different worldviews and cultures can communicate effectively so as to decrease violence and xenophobia. -

Grass Roots Movements Are Redefining Revolution

number 37 summer/fall • 2018 second issue of volume xv Newsstand $5ºº green horiZon Magazine . AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE GREEN HORIZON FOUNDATION . Grass Roots Movements are Redefining Revolution A CALL FOR SUPPORT + OF THOSE IN MOTION . table contents of A Memorial for In Memory of Rhoda Gilman ......... 2 JOHN RENSENBRINK The Green Horizon Team ............ 2 RHODA GILMAN JOHN RENSENBRINK Fifty Years: What We’ve Learned ..... 3 STEVE WELZER hoda Gilman of St. Paul, Minnesota, and ran for lieutenant governor on the MOVEMENT Rdied on May 13, 2018 at the age Green ticket in 2002. She edited and wrote of 92. Her place in the history of about Minnesota’s radical political tradition, Did You Say “THE Movement?” ...... 4 Green JOHN RENSENBRINK Horizon is classic. She was an outstanding including the Minnesota Book Award leader on our Board for many years, nominee “Ringing in the Wilderness” The 3-Ds of the Greening Movement .. 7 STEVE WELZER giving us the gravitas of her wisdom on (1996). In 2008 she received the Vincent many occasions, some of which were L. Hawkinson Foundation award for her Green Independent and the Power of difficult, complex, and sensitive. Though work on peace and social justice. “Yes” ........................... 10 KATE SCHROCK a person of limited means, she coupled The Minnesota Green Party’s memorial her counsel with steady and generous states that Rhoda exemplified the “protest Take a Peek Inside: Criticism and Self-Criticism ......... 13 financial support. On behalf of all of us tradition” in Minnesota that she wrote ROMI ELNAGAR here at Green Horizon, we mourn her about in her final published book, “Stand death and we celebrate her life. -

Curriculum Windows WHATCURRICULUM THEORISTS of the 197OS CAN TEACH US ABOUT SCHOOLS and Society TODAY

,I Curriculum Windows WHATCURRICULUM THEORISTS OF THE 197OS CAN TEACH US ABOUT SCHOOLS AND SOCIEtY TODAY \ Thc;tmas�It-- s. fl'oattar and Kally Waldrop Curriculum Windows: What Curriculum Theorists of the 1970s Can Teach Us About Schools and Society Today Curriculum Windows: What Curriculum Theorists of the 1970s Can Teach Us About Schools and Society Today Edited by Thomas S. Poetter and Kelly Waldrop INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The CIP data for this book can be found on the Library of Congress website (loc.gov). Paperback: 978-1-62396-918-9 Hardcover: 978-1-62396-919-6 eBook: 978-1-62396-920-2 Copyright © 2015 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfi lming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS Foreword: Meaningful Curriculum Windows from the 1970s ............ix William H. Schubert Preface .................................................................................................. xxiii Kelly Waldrop Introduction: Curriculum Windows of the 1970s—Coming of Age .......................................................................xxvii Thomas S. Poetter 1. Revealing the Hidden Through a Curriculum Window ....................... 1 Yue Li Overly, N. (Ed.). (1970). The unstudied curriculum: Its impact on children. Washington DC: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, NEA. 2. Eyes Wide Shut ........................................................................................ 15 Robert Hendricks Weinstein, M., & Fantini, G. (Eds.). (1970). Toward humanistic education: A curriculum of affect. New York, NY: Praeger Publishing. 3. The Second Read ..................................................................................... 29 Rayshawn L. -

Verdi Opera to Be Set in WWI-Era Spain

Vol. 25 No. 19 FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 www.collegianonline.com Verdi opera to be set in WWI-era Spain In the know: By: HEIDI WILLARD Staff Writer Daylight Saving Time “Spain did not enter the Don’t forget to turn war, but the war entered your clocks one hour Spain, and its economic ahead Saturday night for and political impact eroded daylight saving time. the fragile foundations of the political system.” This White Glove quote by author Francisco J. Tomorrow is the Univer- Romero Salvadó inspired the sity’s spring cleaning day setting for this year’s opera,Il in the residence halls. Trovatore. Inspection will take place Il Trovatore was originally from 5 until 5:45 p.m. set in the 1400s, but Dr. Dar- ren Lawson, the director of Concert, Opera this production, chose to set & Drama Series the opera in Spain in 1914, a The University Opera time of civil unrest. “This is Association will present Il the most modern period in Trovatore Tuesday, Thurs- which we’ve set one of our day and next Saturday operas,” Dr. Lawson said. at 8 p.m. in Rodeheaver Because the plot of Il Auditorium. Trovatore is rather complex, a video has been incorporated Actors portray Manrico and Leonora, the hero and heroine in Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore. Photo: Amy Roukes into the production to “help the story along,” said Jill Iles, a junior speech pedagogy CSC seeks blood donors to save lives, one pint at a time major and assistant director to Dr. Lawson. BJU. She says it’s rewarding balanced meals. -

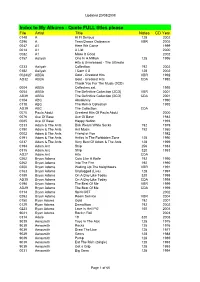

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

Open Brown SHC Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC AND SLAVIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES THE EARLY COMPOSITIONAL EDUCATION OF SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A SURVEY OF PEDAGOGY, AESTHETICS, AND INFLUENCE LAURA BROWN SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Music and Russian with interdisciplinary honors in Music and Russian Reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles D. Youmans Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Mark E. Ballora Associate Professor of Music Honors Adviser Adrian J. Wanner Professor of Slavic and Comparative Literature Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT As the creative mind behind Peter and the Wolf—perhaps the most time-tested childhood staple from the world of orchestral music—Sergey Prokofiev has touched the musical experiences of children across the world for generations. This composer, however, was not only one of the most accomplished musical personalities of the twentieth century, but also a composer who had enjoyed a remarkable childhood of his own. Sergey Prokofiev was one of the youngest and most accomplished pupils ever admitted to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. This thesis investigates why. Prokofiev was already writing operas on fantastic, fairy-tale subjects at the age of nine. He had an appetite for the spotlight and a determination to be taken seriously, even from a young age. What would happen, then, when such a precocious youth was taken seriously? In the summer of 1902, when Prokofiev was eleven years old, Reinhold Glière—a promising graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, preceded only by his reputation as a gold medalist in composition and the endorsement of his former Moscow mentors—stepped off a train in Sontsovka, Ukraine to become Prokofiev’s first significant professional music teacher. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Yiddish Songs of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Yiddish Songs of the Shoah A Source Study Based on the Collections of Shmerke Kaczerginski A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Bret Charles Werb 2014 Copyright © Bret Charles Werb 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Yiddish Songs of the Shoah A Source Study Based on the Collections of Shmerke Kaczerginski by Bret Charles Werb Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Timothy Rice, Chair This study examines the repertoire of Yiddish-language Shoah (or Holocaust) songs prepared for publication between the years 1945 and 1949, focusing its attention on the work of the most influential individual song collector, Shmerke Kaczerginski (1908-1954). Although a number of initiatives to preserve the “sung folklore” of the Nazi ghettos and camps were undertaken soon after the end of the Second World War, Kaczerginski’s magnum opus, the anthology Lider fun di getos un lagern (Songs of the Ghettos and Camps), published in New York in 1948, remains unsurpassed to this day as a resource for research in the field of Jewish folk and popular music of the Holocaust period. ii Chapter one of the dissertation recounts Kaczerginski’s life story, from his underprivileged childhood in Vilna, Imperial Russia (present-day Vilnius, Lithuania), to his tragic early death in Argentina. It details his political, social and literary development, his wartime involvement in ghetto cultural affairs and the underground resistance, and postwar sojourn from the Soviet sphere to the West. Kaczerginski’s formative years as a politically engaged poet and songwriter are shown to have underpinned his conviction that the repertoire of salvaged Shoah songs provided unique and authentic testimony to the Jewish experience of the war. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Gaycalgary and Edmonton Magazine #55, May 2008 Table of Contents 5 Music Lives Here Letter from the Publisher

May 2008 Issue 55 FREE of charge OOnene oonn OOnene IInterviews:nterviews: FFairyTalesairyTales X GGeorgeeorge TakeiTakei X MMarksarks tthehe SSpotpot fforor TTenen YYearear AAnniversarynniversary SSportyporty SSpicepice PPaulaul VVickersickers AAndnd MMORE!ORE! PPre-Pridere-Pride GuideGuide EEarlyarly IInfonfo oonn PPageage 1144 GGayCalgaryayCalgary atat thethe JunosJunos FFeist,eist, BBublé,ublé, RRussellussell PPeterseters aandnd mmore!ore! >> STARTING ON PAGE 16 GLBT RESOURCE • CALGARY & EDMONTON 2 gaycalgary and edmonton magazine #55, May 2008 Table of Contents 5 Music Lives Here Letter from the Publisher Established originally in January 1992 as Men For Men BBS by MFM 7 FairyTales Communications. Named changed to X Marks the Spot for Ten Year Anniversary GayCalgary.com in 1998. Stand alone company as of January 2004. First Issue 9 GayCalgary at the Junos of GayCalgary.com Magazine, November A Look at Canadian Music’s Biggest Week 2003. Name adjusted in November 2006 to GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine. 11 RENT 63 Publisher Steve Polyak & Rob Diaz-Marino, Experience a Season of Love [email protected] 12 Theory of a Deadman Editor Rob Diaz Marino, editor@gaycalgary. 16 com Bearing their Scars and Souvenirs Original Graphic Design Deviant Designs 14 Pre-Pride Event Listing Advertising Calgary and Edmonton Steve Polyak [email protected] Contributors 16 Map & Event Listings Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz-Marino, Jason Clevett, Find out what’s happening Jerome Voltero, Kevin Alderson, Allison Brodowski , Mercedes Allen, Stephen Lock, Dallas Barnes, Benjamin Hawkcliffe, Andrew 23 When the Past Returns Collins, Felice Newman, Romeo San Vicente, ...to Bite Us in the Butt and the Gay and Lesbian Community of Calgary and Edmonton 25 Q Scopes Photographer “Articulate conflicts, Cancer!” Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino Videographer 26 Adult Film Review Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz-Marino Berlin, Itch, Dudes and Holes Please forward all inquiries to: GayCalgary and Edmonton Magazine 28 Deep Inside Hollywood Suite 403, 215 14th Avenue S.W. -

Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Sara Murdock 2018 © Copyright by Sara Murdock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange by Sara Murdock Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor David H. Gere, Chair This dissertation focuses on the concept of social equity in the context of performing arts-based cultural exchange. The work draws upon with Performance Studies and Cultural Studies, reviews several examples through Critical Race Studies and Memory Studies lenses, and then makes advances in Whiteness Studies. All cases revolve around the performing arts as a vehicle for bridging difference. From a practical vantage, the dissertation reviews how organizations do or do not succeed in activating their intentions in an equitable fashion. The document culminates in a Checklist for Social Good, offering a tangible way to link programmatic intentions with implementation. Fieldwork cited includes interviews, ethnographies, and participant observations to determine how programmatic design within cultural exchange has affected social narratives, such as whose cultures have value and on whose terms the programs progress. The dissertation is ii particularly concerned with the ways in which different worldviews and cultures can communicate effectively so as to decrease violence and xenophobia. While no one means of communication across difference is superior, the project focuses on art, and specifically performance, as a means of dialogue and sense-based learning that augments other, sometimes superficial, forms of encounter.