Curriculum Windows WHATCURRICULUM THEORISTS of the 197OS CAN TEACH US ABOUT SCHOOLS and Society TODAY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Amii Stewart

Amii Stewart Ha iniziato le lezioni di ballo quando aveva 9 anni. Dopo 8 anni ha vinto una borsa di studi presso la prima scuola delle belle arte a Washington D.C. “Workshops For Careers In The Arts”, perfezionando il suo talento naturale per il ballo, recitazione ed il canto sotto la tutela di Mike Malone, Lewis Johnson, Debbie Allen, Charles Augins, Robert Hooks e Bernice Regan. Dal 1975 al 1978 Musicals “Bubbling Brown Sugar”: come ballerina nelle Compagnie di Miami e Broadway. Poi nella Compagnia di Londra come Interprete, Assistente della Coreografia e della Regia. “Toby Time”: Interprete, New York. “All God’s Children”: Assistente Coreografa, Prima Ballerina nello Special televisivo per il canale londinese BBC. Discografia: L.P. “Knock On Wood”, (otto millioni di dischi venduti, n°1 in tutte le classifiche mondiali.) Video: “Knock On Wood”, “Light My Fire” Premi: “Migliore artista europea per il Disco Music”, Nomina alla Grammy Awards, “Migliore esibizione” nel “Tokyo Music Festival””. Dal 1979 al 1981 Discografia: L.p.:“Paradise Bird”, (più di 500.000 copie vendute,) prodotto da Barry Lang 45 giri: “Jealousy “- “Light My Fire” (premiati con dischi d’oro) prodotto da Barry Lang L.p.: “I’m Gonna Get Your Love”, prodotto da Narada Michael Walden. Tour Promozionale: U.S., Europa, Messico, Sud America, Japone, Canada. Televisione: U.S.: “The Merv Griffin Show”, “The Dinah Shore Show” e “Soul Train”, Presentatrice dello spettacolo “Midnight Special”. U.K.: “The Terry Woogan Show”, “Top Of The Pops”, e “The Royal Command Performance” per la Regina D’Ingilterra. Video : “Paradise Bird”,”Jealousy’‘, My Girl My Guy’ (duetto con Johnny Bristol). -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/46p561r4 Author Murdock, Sara Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Sara Murdock 2018 © Copyright by Sara Murdock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Designing for Equity: Social Impact in Performing Arts-Based Cultural Exchange by Sara Murdock Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor David H. Gere, Chair This dissertation focuses on the concept of social equity in the context of performing arts-based cultural exchange. The work draws upon with Performance Studies and Cultural Studies, reviews several examples through Critical Race Studies and Memory Studies lenses, and then makes advances in Whiteness Studies. All cases revolve around the performing arts as a vehicle for bridging difference. From a practical vantage, the dissertation reviews how organizations do or do not succeed in activating their intentions in an equitable fashion. The document culminates in a Checklist for Social Good, offering a tangible way to link programmatic intentions with implementation. Fieldwork cited includes interviews, ethnographies, and participant observations to determine how programmatic design within cultural exchange has affected social narratives, such as whose cultures have value and on whose terms the programs progress. The dissertation is ii particularly concerned with the ways in which different worldviews and cultures can communicate effectively so as to decrease violence and xenophobia. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

Grass Roots Movements Are Redefining Revolution

number 37 summer/fall • 2018 second issue of volume xv Newsstand $5ºº green horiZon Magazine . AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE GREEN HORIZON FOUNDATION . Grass Roots Movements are Redefining Revolution A CALL FOR SUPPORT + OF THOSE IN MOTION . table contents of A Memorial for In Memory of Rhoda Gilman ......... 2 JOHN RENSENBRINK The Green Horizon Team ............ 2 RHODA GILMAN JOHN RENSENBRINK Fifty Years: What We’ve Learned ..... 3 STEVE WELZER hoda Gilman of St. Paul, Minnesota, and ran for lieutenant governor on the MOVEMENT Rdied on May 13, 2018 at the age Green ticket in 2002. She edited and wrote of 92. Her place in the history of about Minnesota’s radical political tradition, Did You Say “THE Movement?” ...... 4 Green JOHN RENSENBRINK Horizon is classic. She was an outstanding including the Minnesota Book Award leader on our Board for many years, nominee “Ringing in the Wilderness” The 3-Ds of the Greening Movement .. 7 STEVE WELZER giving us the gravitas of her wisdom on (1996). In 2008 she received the Vincent many occasions, some of which were L. Hawkinson Foundation award for her Green Independent and the Power of difficult, complex, and sensitive. Though work on peace and social justice. “Yes” ........................... 10 KATE SCHROCK a person of limited means, she coupled The Minnesota Green Party’s memorial her counsel with steady and generous states that Rhoda exemplified the “protest Take a Peek Inside: Criticism and Self-Criticism ......... 13 financial support. On behalf of all of us tradition” in Minnesota that she wrote ROMI ELNAGAR here at Green Horizon, we mourn her about in her final published book, “Stand death and we celebrate her life. -

Liberty Magazine January 2002.Pdf Mime Type

Terror, War, and January 2002 ------------$4.00 Rock'n' Roll "Never has a law formed a man: Liberty that breeds giants and heroes. 11 - Schiller January 2002 Inside Liberty Volume 16, Number 1 4 Letters Our critics, and very best friends. 7 Reflections We name the wrong names, fall in love with the state all over again, haul Beelzebub before The Hague, get slapped with a torture warrant, and die fat and happy in the 'burbs. Features 21 Microsoft Capitulates In settling their antitrust battle, Microsoft and the government both surrendered something, Dave Kopel explains, but the real losers were computer users and justice in America. 25 Terror, War, and Rock 'n' Roll As Sarah McCarthy demonstrates, New York City, a Pakistani cab driver, and MickJagger's body add up to one hell of a weekend. 29 Toward Martial Law Robert Levy introduces you to the USA PATRIOT Act. Well, the Bill of Rights was nice while it lasted. 31 The Mussolini of Maui Drastic times call for drastic measures. At least that's what Hawaii's governor would like us to believe. Malia Zimmerman profiles the biggest, baddest, power-hungriest governor since Huey Long. 33 Muslims in Paradise Alexander Boldizar explores an island where tourists roam, religious strife abounds, and every 50 years the elite fight to the death. 37 New Perspectives on the Cold War For almost a half century, the Cold War was the greatest threat to human life. Or was it? Stephen Browne offers a perspective from Eastern Europe. 41 Open Minds, Closed Borders Open borders mean prosperity, freedom, and happiness. -

Verdi Opera to Be Set in WWI-Era Spain

Vol. 25 No. 19 FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 www.collegianonline.com Verdi opera to be set in WWI-era Spain In the know: By: HEIDI WILLARD Staff Writer Daylight Saving Time “Spain did not enter the Don’t forget to turn war, but the war entered your clocks one hour Spain, and its economic ahead Saturday night for and political impact eroded daylight saving time. the fragile foundations of the political system.” This White Glove quote by author Francisco J. Tomorrow is the Univer- Romero Salvadó inspired the sity’s spring cleaning day setting for this year’s opera,Il in the residence halls. Trovatore. Inspection will take place Il Trovatore was originally from 5 until 5:45 p.m. set in the 1400s, but Dr. Dar- ren Lawson, the director of Concert, Opera this production, chose to set & Drama Series the opera in Spain in 1914, a The University Opera time of civil unrest. “This is Association will present Il the most modern period in Trovatore Tuesday, Thurs- which we’ve set one of our day and next Saturday operas,” Dr. Lawson said. at 8 p.m. in Rodeheaver Because the plot of Il Auditorium. Trovatore is rather complex, a video has been incorporated Actors portray Manrico and Leonora, the hero and heroine in Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore. Photo: Amy Roukes into the production to “help the story along,” said Jill Iles, a junior speech pedagogy CSC seeks blood donors to save lives, one pint at a time major and assistant director to Dr. Lawson. BJU. She says it’s rewarding balanced meals. -

Brass Events

Required Music List BRASS EVENTS 2016-17 -- 2021-22 This Association is governed by an elected State Board consisting of three music teachers and one school administrator from each of the eight zones in Indiana. Rules and Regulations of all events are determined through procedures as prescribed in the ISSMA Music Festivals Manual. All festivals are administered and coordinated through the ISSMA office. Please direct all inquiries to: Indiana State School Music Association, Inc. www.issma.net All Directors Please Note It is important to refer to the Solo and Ensemble required manuals listed on the official ISSMA web site to validate and retrieve the most current information. Any publication posted on the ISSMA, Inc. website will supersede any previously printed edition. Unless a particular editor or arranger is specified, any standard, unabridged, unarranged edition is acceptable. SPECIFIC INFORMATION PERTAINING TO BRASS EVENTS * Indicates selection is Permanently Out of Print The following abbreviations specify instrumentation used in ensembles: trpt = Trumpet hrn = French Horn btrb = Bass Trombone cor = Cornet mel = Mellophone bar = Baritone picc = Piccolo Trpt. alth = Alto Horn euph = Euphonium flgl = Flugelhorn trb = Trombone tba = Tuba NOTE: EVENT NO. 053, Mellophone/Alto Horn Solos, now has its own independent list. Selections that are specified for Alto Horn only are indicated as such on the list. NOTE: EVENT NO. 055, Bass Trombone Solos, and EVENT NO. 056, Euphonium or Baritone Solos, have their own independent lists that have been expanded to include selections from other required lists. Students entering either of these events must play a selection from the indicated list. -

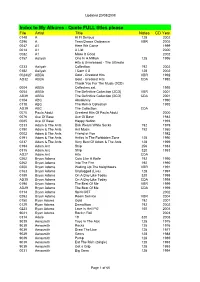

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

Abstract Spring, Mark Jeremy

ABSTRACT SPRING, MARK JEREMY. Teaching a Practical Philosophy of Mind: Design, Rationale, & Illustration of a Philosophy-Based ELA Curriculum Model. (Under the direction of Drs. Angela Wiseman and Ruie Pritchard). This study presents an intricate design and illustration of a high school ELA curriculum model conceived to help students improve their critical thinking and interpretation skills. The model is infused with philosophy-based exercises that prompt students to closely examine their thinking as part of their ELA coursework. Writings by the early pragmatist philosophers, reader response theorist Louise Rosenblatt, and critical thinking scholars provide fine-grained analyses of reading, writing, and thinking, all of which inform the design for each model stage. The final two chapters of this study feature close examination of the model in action. I use qualitative content analysis to peruse 70 artifacts created by ten students who were immersed in the ELA curriculum model’s connected stages. I report my findings in three layers of analysis: close study of the teacher’s perspective; detailed analysis of a student’s complete learning arc; and comparison and contrast of artifacts that all ten study participants created throughout the course. The findings of this study provide a foundation for answering two research questions, the first concerning how high school ELA teachers can guide students to develop a practical philosophy of mind, and the second concerning how student work displays critical thinking and interpretation. These findings provide a foundation for curriculum design and open a path for focused research on how teachers in ELA and across disciplines can use studies of critical thinking, reader response, and pragmatism to create standards-aligned exercises that spark critical thinking, interpretation, and development of a practical philosophy of mind. -

Open Brown SHC Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC AND SLAVIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES THE EARLY COMPOSITIONAL EDUCATION OF SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A SURVEY OF PEDAGOGY, AESTHETICS, AND INFLUENCE LAURA BROWN SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Music and Russian with interdisciplinary honors in Music and Russian Reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles D. Youmans Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Mark E. Ballora Associate Professor of Music Honors Adviser Adrian J. Wanner Professor of Slavic and Comparative Literature Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT As the creative mind behind Peter and the Wolf—perhaps the most time-tested childhood staple from the world of orchestral music—Sergey Prokofiev has touched the musical experiences of children across the world for generations. This composer, however, was not only one of the most accomplished musical personalities of the twentieth century, but also a composer who had enjoyed a remarkable childhood of his own. Sergey Prokofiev was one of the youngest and most accomplished pupils ever admitted to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. This thesis investigates why. Prokofiev was already writing operas on fantastic, fairy-tale subjects at the age of nine. He had an appetite for the spotlight and a determination to be taken seriously, even from a young age. What would happen, then, when such a precocious youth was taken seriously? In the summer of 1902, when Prokofiev was eleven years old, Reinhold Glière—a promising graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, preceded only by his reputation as a gold medalist in composition and the endorsement of his former Moscow mentors—stepped off a train in Sontsovka, Ukraine to become Prokofiev’s first significant professional music teacher.