Politics, Shipping, and Pirates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

A Pirate's Life for Me

A Pirate’s Life for Me 1| Page April 13th Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Table of Contents Staff Introductions…………………………………………………………………………………..……....3-4 Crisis Overview………………………………………………………………………………………......…...5 Pirate History………………………………..……………………………………………….…………....….6-10 Features of the Caribbean……………...…………………………………………….……………....….11-13 Dangers of the Sea………………………………………………………………………………….………..13-14 Character List…………………….…………………………………………………………….…...…….......14-24 Citations/Resources………..…………………………………………………………………..…………...25-26 Disclaimers…………….…………………………………………………………...………………………......26-27 2| Page Staff Introductions Head Crisis Staff - Sarah Hlay Dear Delegates, Hello and welcome to the “It’s A Pirate’s Life For Me” Committee! I am very excited to have all of you as a part of my committee to learn and explore the era that is the Golden Era of Piracy. My name is Sarah Hlay and I will be your Crisis Director for this committee. I am a junior at Kutztown University and this is my fourth semester as a part of Kutztown Model UN. This is my second Kumunc but first time running my own crisis. I am excited for you all to be part of my first crisis and to use creative problem solving together over the course of our committee. Pirate history is something that has always fascinated me and is a topic I enjoy learning more about each day. I’m excited to share my love and knowledge of this topic within one of the best eras that have existed. I hope to learn as much from me as I will from you. At Kutztown, I am studying Art Education and although I am not part of the Political Science department does not mean that debating and creative thinking is something I’m passionate about. -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

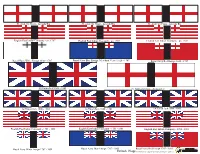

British Flags Permission to Copy for Personal Gaming Use Granted GAME STUDIOS

St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – CrossEnglish - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – Cross English - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – EnglishCross - flArmada ag of the Era Armada Era EnglishEnglish East IndianIndia Company Company - -pre pre 1707 1707 EnglishEnglish East East Indian India Company - pre 1707 EnglishEnglish EastEast IndianIndia Company Company - - pre pre 1707 1707 Standard Royal Navy Blue Squadron Ensign, Royal Navy White Ensign 1630 - 1707 Royal Navy Blue Ensign /Merchant Vessel 1620 - 1707 RoyalRoyal Navy Navy Red Red Ensign Ensign 1620 1620 - 1707 - 1707 1st Union Jack 1606 - 1801 St. Andrews Cross - Armada Era 1st1st UnionUnion fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 1st1st Union Union Jack fl ag, 1606 1606 - 1801- 1801 1st1st Union Union fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 Royal Navy White Ensign 1707 - 1801 Royal Navy Blue Ensign 1707 - 1801 RoyalRed Navy Ensign Red as Ensignused by 1707 Royal - 1801Navy and ColonialSEA subjects DOG GAME STUDIOS British Flags Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted GAME STUDIOS . Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag SEA DOG Dutch Flags GAME STUDIOS Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted. -

2019 Annual Report Bryn Mawr Film Institute

PLACEHOLDER 2019 ANNUAL REPORT BRYN MAWR FILM INSTITUTE 2019 1 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 1 MISSION 2 2019 FILMS SCREENED 3 2019 STAGE ON SCREEN 6 SPECIAL EVENTS 7 2019 IN POSTERS 10 FINANCES 11 UNRESTRICTED GIFT DONORS 13 ENDOWMENT AND OPERATIONAL SUPPORT 17 EDUCATION DONORS 18 MEMBERSHIP LEADERS 19 COMMUNITY AND VOLUNTEERS 21 2019 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 23 2019 BMFI STAFF 24 LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR YESTERDAY AND TODAY Given that this 2019 annual distinguished cinematic style, neighboring zip codes than in report is being written in 2020, our audiences, members and prior years. BMFI continues it becomes unique in that the non-members alike showed to be nationally recognized year covered represents one up in droves. Our courses and as a leader among art house of BMFI’s most successful seminars drew an ever-widening cinemas. We are very proud of in history, yet precedes a group of film enthusiasts, and this reputation, and we plan to period which has been most our data shows us that the maintain it. challenging, due to the more people participate in pandemic. I am confident that our educational offerings, the With your help and support we will be ready and able to more first run films they come through your memberships and welcome everyone back as soon to see together at the theater. generous donations, BMFI will as it is safe to do so. After all, We view this as the perfect continue to be a cultural mecca feature films, since the days reflection of our mission, for our entire area for many of nickelodeons, were always namely to “build community years to come—one that we will intended for group viewing. -

Fall 2020 Tributaries

Tributaries A Publication of the North Carolina Maritime Letter from the Board History Council www.ncmaritimehistory.org Letter from the Editor Fall 2020 Number 18 “Who Pays for That?” The Steamship Twilight and the Tribulations of Post-Civil War Southern Enterprise By: Jeremy Borrelli A Pirate Haven? The Pirates and their Relationship with Colonial North Carolina By: Allyson Ropp Call for Student Representatives Tributaries A Publication of the North Carolina Maritime History Council www.ncmaritimehistory.org Fall 2020 Number 18 Contents Members of the Executive Board 3 Letter from the Board 4 Letter from the Editor 5 Jeremy Borrelli “Who Pays for That?” 7 The Steamship Twilight and the Tribulations of Post-Civil War SouthernEnterprise Allyson Ropp A Pirate Haven? 21 The Pirates and their Relationship with Colonial North Carolina Call for Submissions 32 Call for a Student Representative to the Executive Board 33 Style Appendix 34 Tributaries Fall 2020 1 Tributaries is published by the North Carolina Maritime History Council, Inc., 315 Front Street, Beaufort, North Carolina, 28516-2124, and is distributed for educational purposes www.ncmaritimehistory.org Chair Lynn B. Harris Editor Chelsea Rachelle Freeland Copyright © 2020 North Carolina Maritime History Council North Carolina Maritime History Council 2 Tributaries A Publication Members of the North Carolina Maritime Chair David Bennett Chelsea Rachelle Freeland Lynn B. Harris, Ph.D. Curator of Maritime History Senior Analyst, Cultural Property History Council Professor North Carolina Maritime Museum U.S. Department of State www.ncmaritimehistory.org Program in Maritime Studies (252) 504-7756 (Contractor) Department of History [email protected] Washington, DC 20037 East Carolina University (202) 632-6368 Admiral Eller House, Office 200 Jeremy Borrelli [email protected] Greenville, NC 27858 Staff Archaeologist (252) 328-1967 Program in Maritime Studies Frances D. -

Pirates - V1.0 Pirates Henrik Raun – 22.Jan.1986 – 105 BPM

Henrik Raun - Pirates - V1.0 Pirates Henrik Raun – 22.Jan.1986 – 105 BPM Drum intro – ad lib march style until a round on the drums C1 | G D A Hm | Guitar melody intro – 2 guitars unison (No chords) | G D A Em | | G D A Hm | Emanuel Wynn's flag: | G D Em . | A1 | Am G Dm Am | Pirates for just one day – We’ll kill and rape and then be on our way | Am G Dm Am | Pirates for just one day – Justice will be skipped whatever you’ll say B1 | D Am G Am | We’ll pay with our lives – But first we’ll kill every man child and wife | D Am G Am | We’ll use our knives – To cut out the guts of the government spies C2 | G D A Hm | 2 guitars doing chords – (No melody) | G D A Em | | G D A Hm | Richard Worley's flag: | G D Em . | A2 | Am G Dm Am | Pirates for just one day – When the day is gone we promise to move on | Am G Dm Am | Pirates for just one day – But is seems to me that this day will linger on B2 | D Am G Am | We’ll hang from the gallows – We’ll never know why it ended this way | D Am G Am | We’ll hang from the gallows – It’s not our fault just turned out this way B3 | D Am G Am | At the least resistance – We’ll chop of their heads and feed them to the sharks | D Am G Am | At none resistance – We’ll rape the woman and kill them afterwards C3 | G D A Hm | Henrik doing melody – Peter doing chords | G D A Em | | G D A Hm | Jolly Roger flown by Calico Jack Rackham: | G D Em . -

South Carolina's Maritime History: an Annotated Bibliography, Colonial Period Carl Naylor [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Faculty & Staff ubP lications Institute of 1990 South Carolina's Maritime History: An Annotated Bibliography, Colonial Period Carl Naylor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sciaa_staffpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 1990. Naylor, Carlton A. South Carolina's Maritime History: An Annotated Bibliography, Colonial Period. Columbia, SC: The outhS Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina, 1990. http://www.cas.sc.edu/sciaa/ © 1990 by The outhS Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty & Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUTH CAROLINA'S MARITIME HISTORY An Annotated Bibliography Colonial Period By Carleton A. Nay lor 1990 SOUTH CAROLINA'S MARITIME HISTORY An Annotated Bibliography - Colonial Period - By Carleton A. Naylor (c) 1990 Carleton A. Naylor CONTENTS A: SHIPS, SHIPBUILDING, SHIPWRIGHTS Al: Published Works. ' . .... 1 A2: Periodicals ..... .. 6 A3: Manuscript Collections. .8 A4: Newspapers.... • •• • •.. '. 8 A5: Miscellaneous ......... • •.••••••••• 9 B: SHIPPING, MARITIME COMMERCE, SHIPOWNERS B1: Published Works. ..10 B2: Periodicals ..... ' ..... 14 B3: Manuscript Collections .. ..16 B4: Newspapers ..... .. 18 B5: Miscellaneous .. ... 18 C: PIRATES, PRIVATEERS, NAVAL ACTIVITIES C1~ Published Works .. .20 C2: Periodicals ...•. .22 C3: Manuscript Collections .. .24 C4: Newspapers .... .... 24 C5: Miscellaneous •. .... 25 D: RIVERS, WATERWAYS, PORTS D1: Published Works .. .26 D2: Periodicals .•... .. 28 D3: Manuscript Collections ... .29 D4: Newspapers .......... -

Pirate Articles and Their Society, 1660-1730

‘Piratical Schemes and Contracts’: Pirate Articles and their Society, 1660-1730 Submitted by Edward Theophilus Fox to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maritime History In May 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract During the so-called ‘golden age’ of piracy that occurred in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, several thousands of men and a handful of women sailed aboard pirate ships. The narrative, operational techniques, and economic repercussions of the waves of piracy that threatened maritime trade during the ‘golden age’ have fascinated researchers, and so too has the social history of the people involved. Traditionally, the historiography of the social history of pirates has portrayed them as democratic and highly egalitarian bandits, divided their spoil fairly amongst their number, offered compensation for comrades injured in battle, and appointed their own officers by popular vote. They have been presented in contrast to the legitimate societies of Europe and America, and as revolutionaries, eschewing the unfair and harsh practices prevalent in legitimate maritime employment. This study, however, argues that the ‘revolutionary’ model of ‘golden age’ pirates is not an accurate reflection of reality. -

Annual Report 2017–18

Annual Report 2017–18 1 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 2 Introduction During the 2017–18 season, the Metropolitan Opera presented more than 200 exiting performances of some of the world’s greatest musical masterpieces, with financial results resulting in a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses—the fourth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Bellini’s Norma and also included four other new productions, as well as 19 revivals and a special series of concert presentations of Verdi’s Requiem. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 12th year, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office and media) totaled $114.9 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All five new productions in the 2017–18 season were the work of distinguished directors, three having had previous successes at the Met and one making an auspicious company debut. A veteran director with six prior Met productions to his credit, Sir David McVicar unveiled the season-opening new staging of Norma as well as a new production of Puccini’s Tosca, which premiered on New Year’s Eve. The second new staging of the season was also a North American premiere, with Tom Cairns making his Met debut directing Thomas Adès’s groundbreaking 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel. -

The Specialist Sailor in World War II

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-2021 Below-deck: The Specialist Sailor in World War II Gregory Falcon Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Falcon, Gregory. "Below-deck: The Specialist Sailor in World War II." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000289 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Below-deck: the specialist sailor in World War II A Thesis by Gregory Falcon Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August, 2021 Committee in charge Dr. Jennifer Keene – Chair Dr. Kyle Longley Dr. Alexander Bay The thesis of Gregory Falcon is approved. Jennifer Keene, Ph.D., Chair Kyle Longley, Ph.D. Alexander Bay, Ph.D. June, 2021 Below-deck: the specialist sailor in World War II Copyright © 2021 by Gregory Falcon III ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to a number of people who kept me anchored during this thesis experience. -

Research & Creative Achievement Week

10TH ANNUAL RESEARCH & CREATIVE ACHIEVEMENT WEEK APRIL 4 – 8 2016 MENDENHALL STUDENT CENTER #RCAW2016 @ECUGRADSCHOOL ECU.EDU/GRAD Research & Creative Achievement Week 2016 We would like to give a special thanks to ECU School of Art and Design graphic design undergraduate student Thomas Davis, for his cover design, poster, and program art. We would also like to recognize Doctoral of Physics student Taylor Dement, for his development and management of the abstract book. Table of Contents 06 Letter from Provost Ronald Mitchelson, Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences Phyllis Horns, and Interim Vice Chancellor, Division of Research, Economic Development and Engagement Michael Van Scott 07 Program Sponsers 08 Research and Creative Achievement Week Committees 09 Event Schedule 10 Lectures and Symposia 18 Mentor Listing 19 Student Presenter Schedule 19 Graduate Oral Presentations 24 Graduate Poster Presentations 31 Graduate Online Presentations 32 Post Doctoral Scholar Presentations 33 Undergraduate Oral Presentations 36 Undergraduate Poster Presentations 45 Undergraduate Online Presentations 47 Graduate Abstracts 47 Oral Presentations 73 Poster Presentations 116 Online Presentations 117 Post Doctoral Scholar Abstracts 121 Undergraduate Abstracts 121 Oral Presentations 133 Poster Presentations 188 Online Presentations 191 Presenter Index 5 | RCAW 2016 RCAW 2016 | 6 Program Sponsers Division of Academic Affairs Division of Health Sciences Brody Graduate Student Association Office of Undergraduate Research Office of Postdoctoral Affairs Graduate