Fall 2020 Tributaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

Colonial Office

PU1LIC il",;·-;.'H> O' .L';E L0l1(lo11, En;' II C,l,);r\L ")F'I...;-;;: Am-.~~c'1: ,f St::1tc; 1. 117"), 1'- i\")riL, rli' ...'1,11. Lor d Dnr-rrou Lb ::0 j n"I' '. ':!'Cc') 1J). kilJ l mcn t i.on of Col.• 1;lC1.c'·\n I.:; pr oj c r l: '11 r-ti z;' L; n r erj i ncn t nmon; SC'Jti'3h irnrd,~r'l.,t·, in llo r t h C'1.r~fO.n"l "I_~' L775, 3 rh~'t 4hit(lh',ll.. Dnr t mout h to (Jt~" (c oy), r i c f l~-t;tr.r rer;ardinr. Lo y-i i i o t IC01.i.n; ill t h : IIJ"1("~ o t l Lcmo n t c ;!' 80· tel. (-3 ). 177S, '(~hY, Boston. G" ~c to Dar t moubl, l-j_,," ;c 1.1 ont 0.1 Co]. J'i "1C 1oan '::;1H' 0 j C ct. 80, I 3. I- :L 1775, 12 June, Boston. GLlCC to Dnr t raou Ll; , 31'i':!f "("ire ic o to Hnc10an. ~ O· 11-. \ - i ') . 1775, 2l~ July. Boo t on . GLlGC to Dar bmou tn . Gov o r-nor r: r t i.n and loyalist feel inG in North carol,i~O. Is: I - =:L ,- NNI ln t i () . 1775, "lG Hay, Bcr-u . l r n to GaGe (ropy). Situ,'3tion in Nor t h Ca r o'l i ria [e ncl.os od Vii I:h n')o,'r J. -

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M. Bartos, Administrator Governor Roy Cooper Office of Archives and History Secretary Susi H. Hamilton Deputy Secretary Kevin Cherry July 31, 2020 Braden Ramage [email protected] North Carolina Army National Guard 1636 Gold Star Drive Raleigh, NC 27607 Re: Demolish & Replace NC Army National Guard Administrative Building 116, 116 Air Force Way, Kure Beach, New Hanover County, GS 19-2093 Dear Mr. Ramage: Thank you for your submission of July 8, 2020, transmitting the requested historic structure survey report (HSSR), “Historic Structure Survey Report Building 116, (former) Fort Fisher Air Force Radar Station, New Hanover County, North Carolina”. We have reviewed the HSSR and offer the following comments. We concur that with the findings of the report, that Building 116 (NH2664), is not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places for the reasons cited in the report. We have no recommendations for revision and accept this version of the HSSR as final. Additionally, there will be no historic properties affected by the proposed demolition of Building 116. Thank you for your cooperation and consideration. If you have questions concerning the above comment, contact Renee Gledhill-Earley, Environmental Review Coordinator, at 919-814-6579 or [email protected]. In all future communication concerning this project, please cite the above referenced tracking number. Sincerely, Ramona Bartos, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer cc Megan Privett, WSP USA [email protected] Location: 109 East Jones Street, Raleigh NC 27601 Mailing Address: 4617 Mail Service Center, Raleigh NC 27699-4617 Telephone/Fax: (919) 814-6570/807-6599 HISTORIC STRUCTURES SURVEY REPORT BUILDING 116, (FORMER) FORT FISHER AIR FORCE RADAR STATION New Hanover County, North Carolina Prepared for: North Carolina Army National Guard Claude T. -

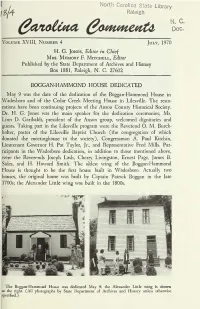

Ally Two Houses, the Original Home Was Built by Captain Patrick Boggan in the Late 1700S; the Alexander Little Wing Was Built in the 1800S

North Carolina State Library Raleigh N. C. Doc. VoLUME XVIII, NuMBER 4 JULY, 1970 H. G. JoNES, Editor in Chief MRs. MEMORY F. MITCHELL, Editor Published by the State Department of Archives and History Box 1881, Raleigh, N. C. 27602 BOGGAN-HAMMOND HOUSE DEDICATED May 9 was the date of the dedication of the Boggan-Hammond House in Wadesboro and of the Cedar Creek Meeting House in Lilesville. The resto rations have been continuing projects of the Anson County Historical Society. Dr. H. G. Jones was the main speaker for the dedication ceremonies; Mr. Linn D. Garibaldi, president of the Anson group, welcomed dignitaries and guests. Taking part in the Lilesville program were the Reverend 0. M. Burck halter, pastor of the Lilesville Baptist Church (the congregation of which donated the meetinghouse to the society), Congressman A. Paul Kitchin, Lieutenant Governor H. Pat Taylor, Jr., and Representative Fred Mills. Par ticipants in the Wadesboro dedication, in addition to those mentioned above, were the Reverends Joseph Lash, Cherry Livingston, Ernest Page, James B. Sides, and H. Howard Smith. The oldest wing of the Boggan-Hammond House is thought to be the first house built in Wadesboro. Actually two houses, the original home was built by Captain Patrick Boggan in the late 1700s; the Alexander Little wing was built in the 1800s. The Boggan-H3mmond House was dedicated May 9; the Alexander Little wing is shown at the right. (All photographs by State Department of Archives and History unless otherwise specified.) \ Pictured above is the restored Cedar Creek Meeting House. FOUR MORE NORTH CAROLINA STRUCTURES BECOME NATIONAL LANDMARKS Four North Carolina buildings were designated National Historic Landmarks by the Department of the Interior in May. -

A Pirate's Life for Me

A Pirate’s Life for Me 1| Page April 13th Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Table of Contents Staff Introductions…………………………………………………………………………………..……....3-4 Crisis Overview………………………………………………………………………………………......…...5 Pirate History………………………………..……………………………………………….…………....….6-10 Features of the Caribbean……………...…………………………………………….……………....….11-13 Dangers of the Sea………………………………………………………………………………….………..13-14 Character List…………………….…………………………………………………………….…...…….......14-24 Citations/Resources………..…………………………………………………………………..…………...25-26 Disclaimers…………….…………………………………………………………...………………………......26-27 2| Page Staff Introductions Head Crisis Staff - Sarah Hlay Dear Delegates, Hello and welcome to the “It’s A Pirate’s Life For Me” Committee! I am very excited to have all of you as a part of my committee to learn and explore the era that is the Golden Era of Piracy. My name is Sarah Hlay and I will be your Crisis Director for this committee. I am a junior at Kutztown University and this is my fourth semester as a part of Kutztown Model UN. This is my second Kumunc but first time running my own crisis. I am excited for you all to be part of my first crisis and to use creative problem solving together over the course of our committee. Pirate history is something that has always fascinated me and is a topic I enjoy learning more about each day. I’m excited to share my love and knowledge of this topic within one of the best eras that have existed. I hope to learn as much from me as I will from you. At Kutztown, I am studying Art Education and although I am not part of the Political Science department does not mean that debating and creative thinking is something I’m passionate about. -

Are We a Bunch of Robin Hoods?” Filesharing As a Folk Tradition of Resistance Benjamin Staple

Document generated on 09/27/2021 8:47 a.m. Ethnologies “Are We a Bunch of Robin Hoods?” Filesharing as a Folk Tradition of Resistance Benjamin Staple Crime and Folklore Article abstract Crime et folklore On the edge of the digital frontier, far from the oceans of their maritime Volume 41, Number 1, 2019 namesakes, pirate communities flourish. Called outlaws and thieves, these file-sharers practice a vernacular tradition of digital piracy in the face of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1069852ar overwhelming state power. Based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted with DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1069852ar Warez Scene cracking groups and the Kickass Torrents community, this article locates piracy discourse as a site of contested identity. For file-sharers who embrace it, the pirate identity is a discursively-constructed composite that See table of contents enables users to draw upon (and create) outlaw folk hero traditions to express themselves and affect small-scale change in the world around them. This article argues that pirate culture is more nuanced than popularly depicted and Publisher(s) that, through traditional practice, piracy is a vernacular performance of resistance. Association Canadienne d’Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Staple, B. (2019). “Are We a Bunch of Robin Hoods?”: Filesharing as a Folk Tradition of Resistance. Ethnologies, 41(1), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069852ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2020 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS David M. Williams and Andrew P. White as well as those from the humanities. The (comp.). A Select Bibliography of British and section on Maritime Law lists work on Irish University Theses About Maritime pollution and the maritime environment, and History, 1792-1990. St. John's, Newfound• on the exploitation of sea resources. It is land: International Maritime Economic particularly useful to have the Open Univer• History Association, 1992. 179 pp., geo• sity and the C.NAA. theses listed. graphical and nominal indices. £10 or $20, The subjects are arranged under twenty- paper; ISBN 0-969588-5. five broad headings; there are numerous chronological geographic and subject sub• The establishment of the International and divisions and an author and geographic British Commissions for Maritime History, index to facilitate cross referencing. Though both of which have assisted in the publica• it is mildly irritating to have details some• tion of this bibliography, illustrates the times split between one column and the steadily growing interest in maritime history next, the whole book is generally convenient during the last thirty years. However, the and easy to use. The introduction explains increasing volume of research in this field the reasons for the format of the biblio• and the varied, detailed work of postgradu• graphy, its pattern of classification and the ate theses have often proved difficult to location and availability of theses. This has locate and equally difficult to consult. This recently much improved and an ASLIB bibliography provides access to this "enor• number is helpfully listed for the majority of mously rich resource" (p. -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science