Recollections of a Sailor Boy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

THE PANAMA CANAL REVIEW November 2, 1956 Zonians by Thousands Will Go to Polls on Tuesday to Elect Civic Councilmen

if the Panama Canal Museum Vol. 7, No. 4 BALBOA HEIGHTS, CANAL ZONE, NOVEMBER 2, 1956 5 cents ANNIVERSARY PROGRAM TO BE HELD NOVEMBER 15 TO CELEBRATE FIFTIETH BIRTHDAY OF TITC TIVOLI Detailed plans are nearing completion for a community mid-centennial celebra- tion, to be held November 15, commem- orating the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the Tivoli Guest House. Arrangements for the celebration are in the hands of a committee headed by P. S. Thornton, General Manager of the Serv- ice Center Division, who was manager of the Tivoli for many years. As the plans stand at present, the cele- bration will take the form of a pageant to be staged in the great ballroom of the old hotel. Scenes of the pageant will de- pict outstanding events in the history of the building which received its first guests when President Theodore Roosevelt paid his unprecedented visit to the Isthmus November 14-17, 1906. Arrangements for the pageant and the music which will accompany it are being made by Victor, H. Herr and Donald E. Musselman, both from the faculty of Balboa High School. They are working with Mrs. C. S. McCormack, founder and first president cf the Isthmian Historical Society, who is providing them with the historical background for the pageant. Fred DeV. Sill, well-known retired em- ployee, is in charge of the speeches and introductions of the various incidents in HEADING THIS YEAR'S Community Chest Campaign are Lt. Gov. H. W. Schull, Jr., right, and the pageant. H. J. Chase, manager of the Arnold H. -

September 2019 Volume 20, Issue 9

September 2019 Volume 20, Issue 9 Lest We Forget — Inside This Issue: “The USSVI Submariner’s Creed” Meeting minutes 2 To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who Lost Boats 3 gave their lives in the pursuit of their duties while Undersea Warfare Hist 3 serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, 688 class Life Extension 4 and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of Builders Face Pressures 5 motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of Contact information 9 America and its Constitution. Application form 10 News Brief 1. Next Meeting: At 1100, third Saturday of each month at the Knollwood Sportsman’s Club. Mark your calendars for these upcoming dates: a. SEPTEMBER 21 b. OCTOBER 19 c. NOVEMBER 16 2. Duty Cook Roster: a. SEPTEMBER – TED ROTZOLL b. OCTOBER – MAURICE YOUNG c. NOVEMBER – SEE YOUR NAME HERE! 3. September Birthdays: Ted Rotzoll 8th; Charles Daniels 17th; and Bob Krautstrunk 18th. Happy Birthday, Shipmates! 4. Support the Cobia - Crash Dive is committed to keeping the Cobia healthy. You can help too, even from afar. Join the WI Maritime Museum; www.wisconsinmaritime.org. 5. Clay Hill is collecting pictures from the dedication of the Riverwalk Memorial. Kindly consider sharing copies of your photos with Clay by sending them to him at [email protected]. Crash Dive Meeting Minutes f. Webmaster – If you have August 17, 2019 something to post on the Website, send it to Frank 1. Attendees: Voznak. Waiting for some a. Glenn Barts, Sr. pictures of the memorial b. Herman Mueller dedication to post. -

Black Sailors, White Dominion in the New Navy, 1893-1942 A

“WE HAVE…KEPT THE NEGROES’ GOODWILL AND SENT THEM AWAY”: BLACK SAILORS, WHITE DOMINION IN THE NEW NAVY, 1893-1942 A Thesis by CHARLES HUGHES WILLIAMS, III Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Major Subject: History “WE HAVE . KEPT THE NEGROES’ GOODWILL AND SENT THEM AWAY”: BLACK SAILORS, WHITE DOMINION IN THE NEW NAVY, 1893-1942 A Thesis by CHARLES HUGHES WILLIAMS, III Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, James C. Bradford Committee Members, Julia Kirk Blackwelder Albert Broussard David Woodcock Head of Department, Walter Buenger August 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “We have . kept the negroes’ goodwill and sent them away”: Black Sailors, White Dominion in the New Navy, 1893-1942. (August 2008) Charles Hughes Williams, III, B.A., University of Virginia Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. James C. Bradford Between 1893 and 1920 the rising tide of racial antagonism and discrimination that swept America fundamentally altered racial relations in the United States Navy. African Americans, an integral part of the enlisted force since the Revolutionary War, found their labor devalued and opportunities for participation and promotion curtailed as civilian leaders and white naval personnel made repeated attempts to exclude blacks from the service. Between 1920 and 1942 the few black sailors who remained in the navy found few opportunities. The development of Jim Crow in the U.S. -

The Jerseyman

3rdQuarter “Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if 2006 again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN END OF AN ERA… BATTLESHIPS USS MAINE USS TEXAS US S NO USS INDIANA RTH U DAK USS MASSACHUSETTS SS F OTA LORI U DA USS OREGON SS U TAH IOWA U USS SS W YOM USS KEARSARGE U ING SS A S KENTUCKY RKAN US USS SAS NEW USS ILLINOIS YOR USS K TEXA USS ALABAMA US S S NE USS WISCONSIN U VAD SS O A KLAH USS MAINE USS OMA PENN URI SYLV USS MISSO USS ANIA ARIZ USS OHIO USS ONA NEW U MEX USS VIRGINIA SS MI ICO SSI USS NEBRASKA SSIP USS PI IDAH USS GEORGIA USS O TENN SEY US ESS USS NEW JER S CA EE LIFO USS RHODE ISLAND USS RNIA COL ORAD USS CONNECTICUT USS O MARY USS LOUISIANA USS LAND WES USS T VI USS VERMONT U NORT RGIN SS H CA IA SS KANSAS WAS ROLI U USS HING NA SOUT TON USS MINNESOTA US H D S IN AKOT DIAN A USS MISSISSIPPI USS A MASS USS IDAHO US ACH S AL USET ABAMA TS USS NEW HAMPSHIRE USS IOW USS SOUTH CAROLINA USS A NEW U JER USS MICHIGAN SS MI SEY SSO USS DELAWARE USS URI WIS CONS IN 2 THE JERSEYMAN FROM THE EDITOR... Below, Archives Manager Bob Walters described for us two recent donations for the Battleship New Jersey Museum and Memorial. The ship did not previously have either one of these, and Bob has asked us to pass this on to our Jerseyman readers: “Please keep the artifact donations coming. -

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History at the Cabildo Chapter 1 Introduction This book is the result of research conducted for an exhibition on Louisiana history prepared by the Louisiana State Museum and presented within the walls of the historic Spanish Cabildo, constructed in the 1790s. All the words written for the exhibition script would not fit on those walls, however, so these pages augment that text. The exhibition presents a chronological and thematic view of Louisiana history from early contact between American Indians and Europeans through the era of Reconstruction. One of the main themes is the long history of ethnic and racial diversity that shaped Louisiana. Thus, the exhibition—and this book—are heavily social and economic, rather than political, in their subject matter. They incorporate the findings of the "new" social history to examine the everyday lives of "common folk" rather than concentrate solely upon the historical markers of "great white men." In this work I chose a topical, rather than a chronological, approach to Louisiana's history. Each chapter focuses on a particular subject such as recreation and leisure, disease and death, ethnicity and race, or education. In addition, individual chapters look at three major events in Louisiana history: the Battle of New Orleans, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Organization by topic allows the reader to peruse the entire work or look in depth only at subjects of special interest. For readers interested in learning even more about a particular topic, a list of additional readings follows each chapter. Before we journey into the social and economic past of Louisiana, let us look briefly at the state's political history. -

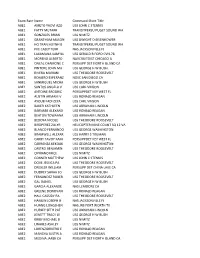

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

Fall 2020 Tributaries

Tributaries A Publication of the North Carolina Maritime Letter from the Board History Council www.ncmaritimehistory.org Letter from the Editor Fall 2020 Number 18 “Who Pays for That?” The Steamship Twilight and the Tribulations of Post-Civil War Southern Enterprise By: Jeremy Borrelli A Pirate Haven? The Pirates and their Relationship with Colonial North Carolina By: Allyson Ropp Call for Student Representatives Tributaries A Publication of the North Carolina Maritime History Council www.ncmaritimehistory.org Fall 2020 Number 18 Contents Members of the Executive Board 3 Letter from the Board 4 Letter from the Editor 5 Jeremy Borrelli “Who Pays for That?” 7 The Steamship Twilight and the Tribulations of Post-Civil War SouthernEnterprise Allyson Ropp A Pirate Haven? 21 The Pirates and their Relationship with Colonial North Carolina Call for Submissions 32 Call for a Student Representative to the Executive Board 33 Style Appendix 34 Tributaries Fall 2020 1 Tributaries is published by the North Carolina Maritime History Council, Inc., 315 Front Street, Beaufort, North Carolina, 28516-2124, and is distributed for educational purposes www.ncmaritimehistory.org Chair Lynn B. Harris Editor Chelsea Rachelle Freeland Copyright © 2020 North Carolina Maritime History Council North Carolina Maritime History Council 2 Tributaries A Publication Members of the North Carolina Maritime Chair David Bennett Chelsea Rachelle Freeland Lynn B. Harris, Ph.D. Curator of Maritime History Senior Analyst, Cultural Property History Council Professor North Carolina Maritime Museum U.S. Department of State www.ncmaritimehistory.org Program in Maritime Studies (252) 504-7756 (Contractor) Department of History [email protected] Washington, DC 20037 East Carolina University (202) 632-6368 Admiral Eller House, Office 200 Jeremy Borrelli [email protected] Greenville, NC 27858 Staff Archaeologist (252) 328-1967 Program in Maritime Studies Frances D. -

Parker-Mastersthesis-2016

Abstract “DASH AT THE ENEMY!”: THE USE OF MODERN NAVAL THEORY TO EXAMINE THE BATTLEFIELD AT ELIZABETH CITY, NORTH CAROLINA By Adam Kristopher Parker December 2015 Director: Dr. Nathan Richards DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Immediately following the Union victory at Roanoke Island (7-8 February 1862), Federal naval forces advanced north to the Pasquotank River and the town of Elizabeth City, North Carolina where remnants of the Confederate “Mosquito Fleet” retreated. The resulting battle led to another Union victory and capture of the Dismal Swamp Canal, thereby cutting off a major supply route for the Confederate Navy from the naval yards at Norfolk, Virginia as well as destroying the Confederate fleet guarding northeastern North Carolina. The naval tactics used in the battle at Elizabeth City have been previously examined using the documentary record; however, little archaeological research has been undertaken to ground truth interpretations of the battle. The present study is an archaeological analysis of the battle using the same framework used by the American Battlefield Protection Program, a military terrain analysis called KOCOA. Since the KOCOA framework was developed as a means to analyze terrestrial battlefields based on modern military theory, questions arise as to whether a traditionally land-focused paradigm is the best way to analyze and understand naval engagements. Hence, the present study considers amending the KOCOA foundation by integrating modern naval theories used by the United States Navy into analysis of a naval battlefield. -

Extensions of Remarks

September 19, 1983 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 24729 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS LEGAL AND ILLEGAL IMMIGRA- Every nation has as one of its sovereign workers employed in this country-34 mil TION: THE IMPACT, THE rights, the right to control the flow of lion people-hold jobs in exactly the kinds CHOICES people into its country. Of the 165 nations of low-skilled industrial, service and agricul on this planet, 164 do so rigidly. Only the tural jobs in which illegal aliens typically United States has a lax immigration policy. find employment, and that 10.5 million HON. BILL LOWERY If you or I were to go to Mexico or Canada, workers are employed at or below the mini OF CALIFORNIA it would be next to impossible under their mum wage. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES laws for us to cross that border, get a job or LEGAL INEQUITIES become productive members of their soci Monday, September 19, 1983 eties. What we have to ask as a nation are Though there are necessarily two parties e Mr. LOWERY of California. Mr. three basic questions: in this offering and accepting of employ First, how many people will we admit to ment, only undocumented foreign nationals Speaker, we will soon be debating the are legally culpable. Worse yet, this legal in most important piece of immigration this country for permanent residency? Two, who will get the slots? Who, of the equity increases the dependence of undocu legislation to come before the Con 600 million people around the world who mented aliens on their employers, making gress in over 20 years. -

Stephen C. Rowan and the US Navy

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2012 Stephen C. Rowan and the U.S. Navy: Sixty Years of Service Cynthia M. Zemke Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Zemke, Cynthia M., "Stephen C. Rowan and the U.S. Navy: Sixty Years of Service" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1263. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1263 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STEPHEN C. ROWAN AND THE U.S. NAVY: SIXTY YEARS OF SERVICE by Cynthia M. Zemke A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History Approved: _____________________ _____________________ S. Heath Mitton Timothy Wolters Committee Chair Committee Member _____________________ _____________________ Denise Conover Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright Cynthia M. Zemke 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Stephen C. Rowan and the U.S. Navy: Sixty Years of Service by Cynthia M. Zemke, Master of Science Utah State University, 2012 Major Professor: Dr. Denise Conover Department: History This thesis is a career biography, and chronicles the life and service of Stephen Clegg Rowan, an officer in the United States Navy, and his role in the larger picture of American naval history.