Capital Injection, Restructuring Targets and Personnel Management: the Case of Japanese Regional Banks∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of the 77 Bank, Ltd Growth Strategy

Strategies of The 77 Bank, Ltd Growth Strategy Best Consulting Bank Human Resource Development In order to become a bank that is truly supported by its customers and to establish a solid management base for the future, we have set the image of the bank we aspire to become as the following, and actively trained specialist resources. Interview 01 “Best Consulting Bank” that responds to customersʼ needs by offering the optimum solutions Striving to solve the issues of quality assurance Corporate Support Department and manpower shortage on the front line of manufacturing. Kei Akama I was assigned to Tohoku Electronics Industry Co., Ltd. with Tohoku Electronics Industry has about 1,000 employees in the headquarters in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture for one year entire group, I was forced to be keenly aware of the issue of the under the Local Company Trainee program that started in 2018. shortage of manpower at the manufacturing front line. I believe I was assigned to the Quality Assurance Department, where I that these valuable experiences as a trainee at a local company dealt with automobile manufacturers and interacted with manu- can be utilized in my current work. I am currently working in the facturing sites to ensure the quality of automobile-related parts. Corporate Support Office, providing support mainly to custom- I was interested in the manufacturing industry, including ers in the fishery processing industry in the coastal areas of the automobiles and machinery, and I thought I had acquired some prefecture that are still on the road to recovery from the Great prior knowledge before I was transferred to the company, but I East Japan Earthquake. -

Regional Banks in Japan 2008

Regional Banks in Japan 2008 We, the 64 regional banks in Japan, have for a long time enjoyed the patronage of the people of our regions as banks that move in step with the community. Hokkaido The Hokkaido Bank The regional banks as financial institutions that have the trust of their customers, will continue to contribute to the activation of regional societies through meeting various financial needs in the regions, by enhancing financial functions such as relationship- based banking. Aomori The Aomori Bank THE MICHINOKU BANK Akita Iwate THE AKITA BANK The Bank of Iwate The Hokuto Bank THE TOHOKU BANK Yamagata THE SHONAI BANK The Yamagata Bank Miyagi The 77 Bank Niigata The Daishi Bank Fukushima The Hokuetsu Bank The Toho Bank Ishikawa Toyama The Hokkoku Bank The Hokuriku Bank THE TOYAMA BANK Tochigi Gunma The Ashikaga Bank Tottori Fukui Nagano The Gunma Bank Ibaraki The Hachijuni Bank The Joyo Bank Shimane THE TOTTORI BANK The Fukui Bank Gifu The San-in Godo Bank Kyoto Saitama The Kanto Tsukuba Bank The Ogaki Kyoritsu Bank The Musashino Bank Hyogo The Bank of Kyoto The Juroku Bank Okayama The Tajima Bank Tokyo Shiga Hiroshima The Chugoku Bank The Tokyo Tomin Bank Fukuoka Yamaguchi The Hiroshima Bank Osaka THE SHIGA BANK Chiba THE BANK OF FUKUOKA The Yamaguchi Bank The Kinki Osaka Bank Aichi The Chikuho Bank The Senshu Bank The Chiba Bank THE NISHI-NIPPON CITY BANK Kagawa The Bank of Ikeda The Chiba Kogyo Bank Saga Ehime The Hyakujushi Bank Mie THE BANK OF SAGA Oita The Iyo Bank The Mie Bank Tokushima Nara THE OITA BANK The Hyakugo Bank -

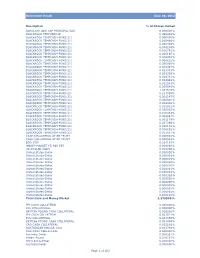

Retirement Funds June 30, 2012 Description % of Shares Owned

Retirement Funds June 30, 2012 Description % of Shares Owned BARCLAYS LOW CAP PRINCIPAL CAS 0.000000% BLACKROCK FEDFUND(30) 0.440244% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000000% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000486% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000485% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008246% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.006791% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.005165% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.006043% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004035% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.035990% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.020497% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.023343% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008326% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000781% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004848% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.022593% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000646% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 1.307615% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.214356% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.001147% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.024810% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.009406% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.018922% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.030062% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.010464% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004697% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.001179% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.007266% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000112% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008062% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.011657% CASH COLLATERAL AT BR TRUST 0.000001% CASH COLLATERAL AT BR TRUST 0.000584% EOD STIF 0.024153% MONEY MARKET FD FOR EBT 0.000000% US DOLLAR CASH 0.008786% United States-Dollar 0.000000% United States-Dollar 0.000003% United States-Dollar 0.000019% United States-Dollar 0.000003% United States-Dollar -

Outline of IWATE UNIVERSITY for International Students a Wide Variety of Research Topics, Made Possible by the Extensive Campus

Outline of I ATE UNIVERSITY for International Students Contact Information Support available in Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean International Office YouTube 3-18-34 Ueda, Morioka-shi, Iwate 020-8550 Japan TEL+81-19-621-6057 / +81-19-621-6076 FAX+81-19-621-6290 E-mail: [email protected] Website Instagram Support available only in Japanese Topic Division/Office in Charge TEL E-mail General Administration and Public Relations About the university in general Division, General Administration Department 019-621-6006 [email protected] Admissions Office, About the entrance exam Student Services Department 019-621-6064 Student Support Division, Facebook About student life Student Services Department 019-621-6060 [email protected] About careers for students Career Support Division, INDEX after graduation Student Services Department 019-621-6709 [email protected] Graduation certificates for graduates and Student Services Division, 1. About Iwate University ………………………………… p.2 students who have completed their studies Student Services Department 019-621-6055 [email protected] 2. Undergraduate and Graduate Programs ………… p.4 3. Research Topics ………………………………………… p.14 Twitter 4. Types of International Students …………………… p.16 5. Support for International Students ……………… p.18 Website Iwate University Japanese English https://www.iwate-u.ac.jp/english/index.html 6. A Day in the Life of an International Student… p.20 Global Education Center Japanese English Chinese Korean https://www.iwate-u.ac.jp/iuic/ 7. Interviews with International Students ………… p.22 Researchers Database Japanese English http://univdb.iwate-u.ac.jp/openmain.jsp 8. Campus Calendar………………………………………… p.23 Questions related to the entrance exam Japanese https://www.iwate-u.ac.jp/admission/index.html WeChat (Chinese International Students Association) 9. -

Current Management Information Briefing

Strategic Business Innovator Current Management Information Briefing June 29, 2017 Yoshitaka Kitao Representative Director, President & CEO SBI Holdings, Inc. The items in this document are provided as information related to the financial results and the business strategy of the SBI Group companies and not as an invitation to invest in the stock or securities issued by each company. None of the Group companies guarantees the completeness of this document in terms of information and future business strategy. The content of this document is subject to revision or cancellation without warning. Note: Fiscal Year (“FY”) ends March 31 of the following year 1 I. SBI Group’s Financial Results for the Past Five Years II. Various Measures for the Next Generation Based on the Changes in the Business Environment 2 I. SBI Group’s Financial Results for the Past Five Years 3 Consolidated Financial Results for the Past Five Fiscal Years (IFRS) [Revenue] Historical high (JPY billion) Financial Services Asset Management 261.7 261.9 Biotechnology-related 4.0 5.5 250 245.0 232.8 2.2 2.2 91.5 80.4 200 65.8 72.7 154.3 150 1.0 33.0 100 177.0 162.6 166.2 147.8 50 113.3 0 FY2012 FY2013 FY2014 FY2015 FY2016 * Abovementioned figures are before elimination of the inter-segment transactions. Also, since there are Group companies that have been transferred from one segment to an another, the abovementioned figures reflect disclosed figures during each fiscal year, therefore, there may be some discrepancies 4 Consolidated Financial Results for the Past Five Fiscal Years (IFRS) [Profit before income tax expense] (JPY billion) Financial Services Asset Management Biotechnology-related 78 63.1 8.1 52.2 68 43.1 58 17.6 13.9 48 38.9 9.0 38 67.3 28 15.0 50.8 48.9 6.3 18 37.3 8 18.7 -2 -7.3 -6.6 -3.9 -2.4 -9.6 -12 FY2012 FY2013 FY2014 FY2015 FY2016 * Abovementioned figures include profit or loss not allocated to specific business segments and inter-segment eliminations. -

Expanding Besta Network

Expanding BeSTA network More than 50 banks are currently using or planning to use BeSTA, core banking software developed by NTT DATA, and the network is the largest of its kind in Japan. Regional Bank Integrated Services Center (14 banks) STELLA CUBE (9 banks) Aomori Bank Bank of Kyoto Tohoku Bank Kanagawa Bank AKITA BANK Senshu Ikeda Bank Tokyo Tomin BankNagano Bank Bank of Iwate TOTTORI BANK TOYAMA BANK Sendai Bank Ashikaga Bank Shikoku Bank Tajima Bank Kirayaka Bank Chiba Kogyo BankOita Bank FUKUHO BANK Hokuetsu Bank NISHI-NIPPON CITY BANK Fukui Bank Aichi Bank MEJAR (5 banks) Hokkaido Bank HOKURIKU BANK BeSTAcloud (10 banks) Bank of Yokohama77 Bank FIDEA Holdings Higashi-Nippon Bank Hokuto Bank SHONAI BANK Aozora Bank NEXTBASE (13 banks) * BeSTA package provided SBK FUKUOKA CHUO BANK Saga Kyoei Bankfrom Hitachi, Ltd. BANK OF NAGASAKI Howa Bank Miyazaki Taiyo Bank MINAMI NIPPON BANK OKINAWA KAIHO BANK Copyright © 2015 NTT DATA Corporation 1 Collaboration concerning BeSTA® banking application and surrounding businesses By combining highly compatible solutions regardless of the frameworks of conventional core banking businesses or other banking businesses, the scope of businesses has been expanded. Ideas on collaboration concerning surrounding businesses are also broadly solicited. Scope expansion Regional Omichannel revitalization Individual-Number Successi BPO Business matching utilization on Payment Regional Cloud/virtualization FINTECH sophistication currency Channel Strategy ATM Branch terminal Business Assets in custody Market management Bank app DM Legal system Assets in custody Financial CRM Integrated DB (investment trust, Contact center Instruments and IFRS insurance) Exchange Act Sales support Financing support Internet banking AML BIS Mobile banking Backbone system (BeSTA) Copyright © 2015 NTT DATA Corporation 2 Priority areas of strategic IT investment Three areas to be studied intensively are operation, data accumulation/analysis, and utilization of external expertise. -

Tokyo Stock Exchange Tokyo Stock Exchange

Tokyo Stock Exchange Annual Report 1998 Year Ended March 31, 1998 Profile or almost 120 years, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) has Fbeen recognized and functioned as Japan’s central stock market. Since its reestablishment in 1949, the TSE has responded positively to trading demands from both overseas and domestic investors, operating both cash and derivatives markets. Now, at the drawn of a new era in which the legal and system- atic framework created by the recent market reforms is taking shape, the TSE is endeavoring to construct and operate a highly efficient and competitive market that will allow it to play a major role in the economic life of Japan, Asia and the world. 3000 2500 2000 1500 CONTENTS Statistical Highlights.....................................3 1000 Message from the President..........................5 TSE Market System.......................................6 Special Feature............................................12 500 Financial Statements...................................14 Board of Governors and Auditors ..............17 List of Members and Special Participants ...20 1970 7172 73 74 75 Statistical Highlights At December 31 1997 1996 1995 (STOCK MARKET) Listed Companies : Domestic .................................................. 1,805 1,766 1,714 : Foreign ..................................................... 60 67 77 Newly Listed Companies : Domestic .................................................. 50 59 32 : Foreign ..................................................... 1 20 Market Value (¥ billions) : Domestic -

DAIWA Earnings Analysis of Major Banks–I

DAIWA DAIWA INSTITUTE OF RESEARCH LTD. 6 December 2007 (No of pages: 19) Earnings Analysis of Major Banks–I —1H FY07 Earnings Summary and Operating Environment— (Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp is affiliated with Daiwa Securities SMBC. See disclaimer below.) Equity Research Dept Akira Takai • Major banks’ aggregate 1H FY07 parent real net business profit (total sum of group banks) edged down 2.6% y/y to Y1,614.8 billion. Domestic net interest income expanded, mainly thanks to improvement in loan-deposit interest rate spreads. Treasury operations apparently improved overall, helped by lower overseas interest rates. Meanwhile, slow growth in net fee/commission income and an increase in overhead weighed on profit. • However, the main factor dragging down profit was aggregate credit costs net of recoveries, which reached Y366.1 billion, reversing course net credit recoveries of Y244.9 booked a year earlier. A number of banks took a hit from earnings deterioration at group non-banks and higher income taxes due to the realization of deferred tax assets during the year-earlier period. This capped aggregate consolidated net income at Y947.9 billion, 45.4% below the 1H FY06 figure, which was the highest in history. However, solid profitability prompted some banks to resume or raise common dividends in 1H. • The BOJ did not raise interest rates in 1H, after having lifted the unsecured overnight call rate 0.25% twice in FY06. The bond market retreated in 1Q but began to rebound in 2Q. Meanwhile, global equity markets pulled back in response to the deepening subprime loan crisis in August, causing Japanese equities to plummet. -

Applying Financial Expertise to Design the Future

Annual Report & CSR ReportAnnual Applying Financial Expertise to Design the Future 2 0 12 http://www.dbj.jp/en Development Bank of Japan Inc. 9-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004, Japan This report is printed on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) as being made from sustainably Development Bank of Japan Inc. managed forests. The report is printed with vegetable ink. All the electricity used in printing and binding this report (600 kWh) was supplied by green resources. Annual Report & CSR Report 2012 Profile (As of September 1, 2012) Established: October 1, 2008 (The Japan Development Bank [1951] and the Hokkaido-Tohoku Development Finance Public Corporation [1956] were merged to form the Development Bank of Japan in 1999) Legal basis: The Development Bank of Japan Inc. Act (Act No. 85 of 2007) President: Toru Hashimoto Number of employees: 1,147 (As of March 31, 2012) Capital: ¥1,198,316 million (100% owned by the Japanese government) Address: 9-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004, Japan URL: http://www.dbj.jp/en Number of offices: Branch offices, 10; representative offices, 8; overseas representative office, 1; and overseas subsidiaries, 2 Subsidiaries and affiliated companies: Consolidated subsidiaries, 17; non-consolidated subsidiaries, 23; and affiliated companies, 15 (As of March 31, 2012) Main business: The provision of long-term funding (investment and loans) Purpose: To conduct business activities utilizing the methods of combining investments and financing and other sophisticated financial methodologies, thereby contributing to the smooth supply of funds to those who need long-term business funds, as well as to the sophistication of financial functions. -

Corporate Profile

CORPORATE PROFILE ACOM CO., LTD. PhiloThe Spirits of Foundatioopn : Circleh ofy Trust ACOM was founded as a draper with credo of “Putting trust on people and winning their trust back.” ACOM was founded as“Maruito Gofuku Ten” in Kobe in 1936. When the founder, Masao Kinoshita, started this business, he promised himself to hold the spirit of mutual trust,“To trust others, and win trust” as a philosophy. The trade name,“Maruito”, was decided since the harmonization of warp and weft, which is linked to an element of the kimono, represents mutual trust. “When one trusts another from bottom of one’s heart, the trust is reciprocated without fail.” We wish to broaden such trust. These are our withes expressed in our spirit of foundation, “Circle of Trust”. We have inherited the spirit of foundation,“Circle of Trust”, as our basis of“corporate philosophy” even in our history of continuous changes. 01 ACOM Corporate Profile President & CEO Masataka Kinoshita By putting the customer first, we aim to become “ACOM that offers New Conveniences” and “Global ACOM” that is well known in the markets of many more countries. We would like to express our sincere gratitude for your continuous patronage to the Group. I assumed the position of President and Chief Executive Officer of the Company as of June 23, 2021. We would like to express our sincere condolences to all those who passed away from the new coronavirus infection. We also would like to offer our heartfelt sympathy to all those who were struck by the new coronavirus infection. We pray for the earliest recovery. -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 The Bank of Iwate, Ltd. Annual Report 2019 Sachio Taguchi President Message from the President Thank you very much for your continued patronage of the Bank of Iwate. In April 2019 we began implementing our new medium-term management plan “Iwagin Frontier Plan – To the Next” (the “Plan”), which will last for a period of four years. The theme of the Plan is “pursuing CSV to build a future with the region.” CSV stands for “Creating Shared Value,” and by confronting the various issues facing our region head on as we execute the Plan, and endeavoring to resolve them, we aim to create shared value and achieve growth for both the community and the Bank. The environment surrounding the Bank is becoming increasingly uncertain, as not only is the local economy shrinking due to a declining population and a shortage of successors, but we are also faced with challenges such as the continuation of negative interest-rate policy by the Bank of Japan and entry into the financial business by firms from other sectors. To tackle this situation and establish co-prosperity with our region, based on which we do the bulk of our business, our executives and employees are all working together to execute various measures in accordance with the Plan. Our corporate message, “Trust, and beyond,” embodies our commitment to gaining the confidence of our customers and then taking that one step further to build a strong relationship of trust with them. Our executives and employees will be working together to make sure that we remain a bank that local customers trust and choose, so we truly hope that we can count on your continued support and patronage. -

Strategies of the 77 Bank, Ltd

Strategies of The 77 Bank, Ltd. E S G The Economy and Growth Potential of Miyagi Prefecture Industrial transformation Increase in visitors ● Expansion of manufacturing industry has created new ● Building a tourism platform Miyagi Prefecture, the primary base of operations for The 77 Bank, is located in the southeast of the Tohoku region. The jobs and grown peripheral industries (e.g., Toyota Motor - Creation of DMO in Sendai/Matsushima (March 2018) About The 77 Bank, Ltd. prefecture is an important crossroads linking Tohoku to Tokyo, the nation’s capital. In 1989, Sendai, the prefectural capital, East Japan and Tokyo Electron Miyagi). - Opening of Miyagi Olle (October 2018) became the 11th city in Japan specially designated by ordinance. The branches and offices of major national businesses ● Toyota Motor East Japan has concentrated production of and organizations, including government agencies, are concentrated in Sendai, thereby positioning Sendai as the compact cars. ● Privatization of Sendai Airport preeminent city of the Tohoku region. In terms of major economic indicators such as population, gross prefectural product, ● Alps Alpine’s new core plant in Japan starts operation. - New routes and increased flights on domestic and and retail sales amount, Miyagi Prefecture ranks around 15th within the nation, and the national share is roughly 2%. international routes Although Miyagi Prefecture experienced significant damage due to the Great East Japan Earthquake, particularly in coastal areas, reconstruction projects have now reached the final phase thanks to joint efforts by the public and private sectors. In addition, with the expansion of major automotive and electronics companies, the manufacturing industry is expected to [Number of offices] [Cumulative total accommodation nights by foreigners] become a driver for post-recovery economic growth while economic concentration is advancing owing to active construction No.1 growth investment related to redevelopment projects in Sendai.