Bering Land National Preserve Junior Ranger Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

The Less-Splendid Isolation of the South American Continent

news and update ISSN 1948-6596 commentary The less-splendid isolation of the South American continent Only few biogeographic scenarios capture the im- lower Central America (Costa Rica) and South agination as much as the closure of the Isthmus of America (northern Colombia), and that some Panama. The establishment of this connection snapping shrimp populations were already split ended the “splendid isolation” of the South Amer- long before the Isthmus had finally closed (most ican continent (Simpson 1980), a continent that between 7–10 mya but some >15 mya). Next to had been unconnected to any other land mass for this, several papers showed that plants also mi- over 50 million years. When the Isthmus rose out grated between North and South America prior to of the water some 3 million years ago (mya) the the closure of the Isthmus (e.g., Erkens et al. 2007, Great American Biotic Interchange started. Since Bacon et al. 2013), although for plants it is difficult terrestrial biotic interchange was no longer to rule out that this happened via long-distance blocked by the Central American Seaway, dispersal. Thus, the new findings of Montes and (asymmetrical) invasion of taxa across this new colleagues fit much better with a wealth of evi- land bridge transformed biodiversity in North as dence from the biological realm that has been well as South America (Leigh et al. 2014). Or so amassed over the last years, than the old model of the story goes. a relatively rapid rise of the Isthmus. A recent paper by Montes et al. (2015) casts If the land-bridge was available much earli- further serious doubt on this scenario from a geo- er to many terrestrial organisms, the question that logical perspective. -

Day 2 Social Studies

Day 2 Social Studies - Read the article "The Earliest Americans" and complete the Build Your Map Skills page and Extinct Animals of North America page. Language Arts - Draw a self-portrait of yourself in the center of a piece of paper. Write a simile that describes parts of yourself. You must have at least 6 similes. For example, I would point to my hair and say "My hair is as red as a tomato." Reminder: a simile is a comparison of two things using like or as. Science- Help! My rose plant is no longer able to carry out photosynthesis, meaning that it can't make its own food anymore. Create an alternate system to keep my rose plant alive . Develop a new system and parts of the plant that will help it be able to obtain nutrients using pictures and descriptions. Math - Look through old magazines and newspapers for 15 numbers that have decimals. Cut out and paste the numbers onto paper in least to greatest order. Use the cut-out numbers to make up five word problems dealing with addition, subtraction, or multiplication. Make a separate key for the problems. Staple the problems and the key to the construction paper. he Earliest Americans. f \ \ Did you ever wonder in what kind of homes the first Americans lived or what kind of food they ate? Anthropologists and archaeologists devote their lives to answering such questions. Anthropologists are scientists who study all aspects of human beings, such as their society and culture. Archaeologists are scientists who use physical evidence and artifacts to analyze human cultures. -

100,000–11,000 Years Ago 75°

Copyrighted Material GREENLAND ICE SHEET 100,000–11,000 years ago 75° the spread of modern humans Berelekh 13,400–10,600 B ( E around the world during A ALASKA la R I ) SCANDINAVIAN n I e Bluefish Cave d N Arctic Circle G g 16,000 d ICE SHEET b G the ice age N i 25,000–10,000 r r i I d I b g e A R d Ice ) E n -fr SIBERIA a Dry Creek e l e B c All modern humans are descended from populations of ( o 35,000 Dyuktai Cvae 13,500 rri do 18,000 r Homo sapiens that lived in Africa c. 200,000 years ago. op LAURENTIDE en s ICE SHEET 1 Malaya Sya Around 60,000 years ago a small group of humans left 4 CORDILLERAN ,0 Cresswell 34,000 0 Africa and over the next 50,000 years its descendants 0 ICE SHEET – Crags 1 2 14,000 colonized all the world’s other continents except Antarctica, ,0 Wally’s Beach 0 Paviland Cave Mal’ta 0 EUROPE Mezhirich Mladecˇ in the process replacing all other human species. These 13,000–11,000 y 29,000 Denisova Cave 24,000 . 15,000 a 33,000 45,000 . Kostenki 41,000 migrations were aided by low sea levels during glaciations, Willendorf 40,000 Lascaux 41,700–39,500 which created land bridges linking islands and continents: Kennewick Cro Magnon 17,000 9,300 45° humans were able to reach most parts of the world on foot. Spirit 30,000 Cave Meadowcroft Altamira It was in this period of initial colonization of the globe that 10,600 Rockshelter 14,000 16,000 Lagar Velho Hintabayashi Tianyuan JAPAN modern racial characteristics evolved. -

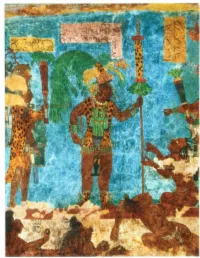

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

Beringia Vocabulary

Beringia Vocabulary 1) artifact--an object made by humans, such as a tool The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass th2a) t acrocnhnaecotloegdy A--sthiae astnudd yN oofr thhis Atomrice raicnad 1pr0e,h0i0s0to-r2ic5 ,000 years ago. Duringp tehoisp lteime, glaciers up to two miles thick covered large parts of North America, Europe and Asia. T3h)e ppaelerioondt owloagsy -c-athllee dst uthdey Pofl eeiasrtloyc leifen eb yIc loeo Akigneg. aSt ome very dry areas weforess iiclse-free during this time. Much of the Earth's water was locked up in the glaciers. Because of th4i)s psereah ilsetvoerilc d--rao pppeeridod s oigfn timficea bnetlfyo, ruep w troit t3e0n0 o fre et! Some areas that are now urencdoerrd weda theisr tboerycame dry land. The result was an intermittent land bridge stretching between 5) fossil--the remains, impression, imprint or bone of the two cao nlivtiinge nthtsin ugnder the present day Bering and Chukchi Seas. Scientists believe that Beringia was at its w6id) e esxtt ipnoctin--ta a sbpoeuctie 1s5 t,h0a0t 0h ayse adriesd a oguot., Anolt hloonuggehr icna lled a "bridge," the leaxnisdt ewnacse really a broad, grassy plain, which many animals stopped to feed on. 7) Pleistocene-- 2 million to 10,000 years ago Beringia The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass 1t0h,a0t0 c0o tnon 2e5c,t0e0d0 A yseiar asn adg No,o drtuhr inAgm teheri cpae r1io0d,0 k0n0o-w2n5 ,a0s0 0th e Pyleeaisrtso caegnoe. IDceu rAingge ,t hgilsa ctiiemrse ,u gpl atoc itewros mupile tso tthwicok mcoilveesr ethdi clakr ge pcaorvtse oref dN olartrhg eA mpaerrtisc ao, fE Nuorortphe ,A amned rAicsaia, Eaundro mpeu cahn odf Athseia e.a rth's wTahter pwearsio ldo cwkaeds ucpa lilne dth teh eg laPcleieirsst.o Tcheen es eIcae le Avegle d. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

Review Unit #2 Early Man and River Civilizations

Review Unit #2 Early Man and River Civilizations Early Man Hunters and Gatherers: During the Paleolithic Stage (Old Stone Age) people wandered behind herds of animals in search of food. The men generally hunted – the women generally gathered berries, nuts, roots, etc. Migration: - Current evidence points to the earliest people having lived in Africa. - They migrated (moved) to other places in the world. - Native Americans migrated across a land bridge from Asia to North America. Cultural Diffusion: - As people migrated and settled together, their ideas mixed. - Trade also caused cultural diffusion. Neolithic Revolution Neolithic Revolution: The change from hunting and gathering to herding and planting. Results of Neolithic Revolution: o Permanent Villages - People built homes and settled together in permanent villages. o New Technology - People had the time to develop new tools and ideas to meet their needs. o Specialization of jobs - Less people were needed to produce food. Some people took on new roles (jobs). Civilizations: - As villages became more developed, some turned into civilizations. - Civilizations can be identified by having certain things: - urban areas (cities) - a writing system - organized economy - an organized government (laws) River Valley Civilizations Why river valleys were great locations to start a civilization: Irrigation: water for crops and human use Annual Flooding: supplied fertile soil for crops each year Transportation: allowed for trade and cultural diffusion Food Supply: fish and other items – -

The Bering Land Bridge: a Moisture Barrier to the Dispersal of Steppe–Tundra Biota?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Quaternary Science Reviews 27 (2008) 2473–2483 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev The Bering Land Bridge: a moisture barrier to the dispersal of steppe–tundra biota? Scott A. Elias*, Barnaby Crocker Geography Department, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK article info abstract Article history: The Bering Land Bridge (BLB) connected the two principal arctic biological refugia, Western and Eastern Received 14 April 2008 Beringia, during intervals of lowered sea level in the Pleistocene. Fossil evidence from lowland BLB Received in revised form 9 September 2008 organic deposits dating to the Last Glaciation indicates that this broad region was dominated by shrub Accepted 11 September 2008 tundra vegetation, and had a mesic climate. The dominant ecosystem in Western Beringia and the interior regions of Eastern Beringia was steppe–tundra, with herbaceous plant communities and arid climate. Although Western and Eastern Beringia shared many species in common during the Late Pleistocene, there were a number of species that were restricted to only one side of the BLB. Among the vertebrate fauna, the woolly rhinoceros was found only to the west of the BLB, North American camels, bonnet-horned musk-oxen and some horse species were found only to the east of the land bridge. These were all steppe–tundra inhabitants, adapted to grazing. The same phenomenon can be seen in the insect faunas of the Western and Eastern Beringia. -

Exploring an Oceanic Influence on the Peopling Of

EXPLORING AN OCEANIC INFLUENCE ON THE PEOPLING OF SOUTH AMERICA An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by DANIELLE MANLEY Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. Sheela Athreya May 2018 Major: Anthropology English TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. 1 Literature Review .............................................................................................................. 1 Thesis Statement ............................................................................................................... 2 Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................................... 4 II. THE BERINGIAN MODEL: ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE ........................... 7 Clovis technology ................................................................................................. 8 Pre-Clovis sites ..................................................................................................... 8 Ice-free corridor ................................................................................................. -

Entering America Northeast Asia and the Beringia Before the Last Glacial

Search Go Subject, Author, Title or Keyword Home Entering America New/Forthcoming Titles Northeast Asia and the Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum Buy Online $50.00 Press Information -- Select -- Edited by D. B. Madsen 400 pp., 6 x 9 Subject Categories 104 illustrations Cloth $50.00 Series ISBN 0-87480-786-7 Archaeology / Anthropology Complete Backlist Where did the first Americans come from and when did they get here? That basic question of American Contact Us archaeology, long thought to have been solved, is re-emerging as a critical issue as the number of well- excavated sites dating to pre-Clovis times increases. It now seems possible that small populations of human 0 Items foragers entered the Americas prior to the creation of the continental glacial barrier. While the archaeological and paleoecological aspects of a post-glacial entry have been well studied, there is little work available on the possibility of a pre-glacial entry. Entering America seeks to fill that void by providing the most up-to-date information on the nature of environmental and cultural conditions in northeast Asia and Beringia (the Bering land bridge) immediately prior to the Last Glacial Maximum. Because the peopling of the New World is a question of international archaeological interest, this volume will be important to specialists and nonspecialists alike. “Provides the most up-to-date information on a topic of lasting interest.” —C. Melvin Aikens, University of Oregon D. B. Madsen is a research associate at the Division of Earth and Ecosystem Science, Desert Research Institute, Reno, and at the Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas, Austin. -

The Central American Land Bridge As an Engine of Diversification in New World Doves

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2011) 38, 1069–1076 ORIGINAL The Central American land bridge as an ARTICLE engine of diversification in New World doves Kevin P. Johnson1* and Jason D. Weckstein2 1Illinois Natural History Survey, University of ABSTRACT Illinois, Champaign, IL 61820, USA, 2Field Aim The closure of the Central American land-bridge connection between North Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA and South America 3.5 million years ago was a major biogeographic event that allowed considerable interchange of the previously isolated faunas of these continents. However, the role that this connection may have had in diversification of North and South American faunas is less well understood. The goal of this study was to evaluate the potential role of the formation of this land connection in generating diversity, through repeated rare dispersal events followed by isolation. Location North and South America. Methods We evaluated the role of the Central American land-bridge connection in avian diversification using a molecular phylogeny based on four gene regions for mid-sized New World doves. Diversification events were dated using a Bayesian relaxed clock analysis and internal calibration points for endemic island taxa with known island ages. Results The reconstructed phylogenetic tree was well supported and recovered monophyly of the genera Leptotila and Zenaida, but the quail-doves (Geotrygon) were paraphyletic, falling into three separate lineages. The phylogeny indicated at least nine dispersal-driven divergence events between North and South America. There were also five dispersal events in the recent past that have not yet led to differentiation of taxa (polymorphic taxa).