The Less-Splendid Isolation of the South American Continent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

Revised Stratigraphy of Neogene Strata in the Cocinetas Basin, La Guajira, Colombia

Swiss J Palaeontol (2015) 134:5–43 DOI 10.1007/s13358-015-0071-4 Revised stratigraphy of Neogene strata in the Cocinetas Basin, La Guajira, Colombia F. Moreno • A. J. W. Hendy • L. Quiroz • N. Hoyos • D. S. Jones • V. Zapata • S. Zapata • G. A. Ballen • E. Cadena • A. L. Ca´rdenas • J. D. Carrillo-Bricen˜o • J. D. Carrillo • D. Delgado-Sierra • J. Escobar • J. I. Martı´nez • C. Martı´nez • C. Montes • J. Moreno • N. Pe´rez • R. Sa´nchez • C. Sua´rez • M. C. Vallejo-Pareja • C. Jaramillo Received: 25 September 2014 / Accepted: 2 February 2015 / Published online: 4 April 2015 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2015 Abstract The Cocinetas Basin of Colombia provides a made exhaustive paleontological collections, and per- valuable window into the geological and paleontological formed 87Sr/86Sr geochronology to document the transition history of northern South America during the Neogene. from the fully marine environment of the Jimol Formation Two major findings provide new insights into the Neogene (ca. 17.9–16.7 Ma) to the fluvio-deltaic environment of the history of this Cocinetas Basin: (1) a formal re-description Castilletes (ca. 16.7–14.2 Ma) and Ware (ca. 3.5–2.8 Ma) of the Jimol and Castilletes formations, including a revised formations. We also describe evidence for short-term pe- contact; and (2) the description of a new lithostratigraphic riodic changes in depositional environments in the Jimol unit, the Ware Formation (Late Pliocene). We conducted and Castilletes formations. The marine invertebrate fauna extensive fieldwork to develop a basin-scale stratigraphy, of the Jimol and Castilletes formations are among the richest yet recorded from Colombia during the Neogene. -

Latest Pliocene Northern Hemisphere Glaciation Amplified by Intensified Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00023-4 OPEN Latest Pliocene Northern Hemisphere glaciation amplified by intensified Atlantic meridional overturning circulation ✉ Tatsuya Hayashi 1 , Toshiro Yamanaka 2, Yuki Hikasa3, Masahiko Sato4, Yoshihiro Kuwahara1 & Masao Ohno1 1234567890():,; The global climate has been dominated by glacial–interglacial variations since the intensifi- cation of Northern Hemisphere glaciation 2.7 million years ago. Although the Atlantic mer- idional overturning circulation has exerted strong influence on recent climatic changes, there is controversy over its influence on Northern Hemisphere glaciation because its deep limb, North Atlantic Deep Water, was thought to have weakened. Here we show that Northern Hemisphere glaciation was amplified by the intensified Atlantic meridional overturning cir- culation, based on multi-proxy records from the subpolar North Atlantic. We found that the Iceland–Scotland Overflow Water, contributing North Atlantic Deep Water, significantly increased after 2.7 million years ago and was actively maintained even in early stages of individual glacials, in contrast with late stages when it drastically decreased because of iceberg melting. Probably, the active Nordic Seas overturning during the early stages of glacials facilitated the efficient growth of ice sheets and amplified glacial oscillations. 1 Division of Environmental Changes, Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies, Kyushu University, 744 Motooka, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan. 2 School of Marine Resources and Environment, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, 4-5-7 Konan, Tokyo 108-8477, Japan. 3 Department of Earth Sciences, Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, 1-1, Naka 3-chome, Tsushima, Okayama 700-8530, Japan. 4 Department of Earth ✉ and Planetary Science, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. -

Day 2 Social Studies

Day 2 Social Studies - Read the article "The Earliest Americans" and complete the Build Your Map Skills page and Extinct Animals of North America page. Language Arts - Draw a self-portrait of yourself in the center of a piece of paper. Write a simile that describes parts of yourself. You must have at least 6 similes. For example, I would point to my hair and say "My hair is as red as a tomato." Reminder: a simile is a comparison of two things using like or as. Science- Help! My rose plant is no longer able to carry out photosynthesis, meaning that it can't make its own food anymore. Create an alternate system to keep my rose plant alive . Develop a new system and parts of the plant that will help it be able to obtain nutrients using pictures and descriptions. Math - Look through old magazines and newspapers for 15 numbers that have decimals. Cut out and paste the numbers onto paper in least to greatest order. Use the cut-out numbers to make up five word problems dealing with addition, subtraction, or multiplication. Make a separate key for the problems. Staple the problems and the key to the construction paper. he Earliest Americans. f \ \ Did you ever wonder in what kind of homes the first Americans lived or what kind of food they ate? Anthropologists and archaeologists devote their lives to answering such questions. Anthropologists are scientists who study all aspects of human beings, such as their society and culture. Archaeologists are scientists who use physical evidence and artifacts to analyze human cultures. -

Carlos Fernando De Gracia

Carlos Fernando De Gracia Institutional Address Department of Paleontology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy University of Vienna Althanstraße 14 / 2A323 1090 Vienna, Austria Phone number Office: +43-1-4277-53530 Personal: +43-677-63736404 e-Mail [email protected] ____________________________________________________________________________ Personal Information ORCID id 0000-0003-0637-3302 Date of birth 2th March, 1986 Place of birth Panama City, Panama Nationality. Panamanian ____________________________________________________________________________ Formal Education 2015 - 2017 Master in Geology, specific field: Geobiology Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic Thesis: Fossil Istiophorids (Perciformes, Istiophoridae) from the Chagres Formation, Panama Year of degree: 2017 Advisor: Tomás Přikryl Co-advisor: Carlos Alberto Jaramillo Scholarship from: Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Czech Republic 2004 - 2010 B. Sc. in Biology, specific field: animal biology Universidad de Panamá, Panama City, Panama Thesis: Structure of benthic communities on the pacific coast of Panama and Costa Rica during the formastion of Central American Ithmus, Year of degree: 2010 Advisors: Aaron O’Dea, Luis D´Croz 2014 - 2015 Improvement Course in Czech Language Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic Scholarship from: Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports ____________________________________________________________________________ Complementary Education 2011 - 2011 Postgraduate Course in Tropical -

Consequences of Shoaling of the Central American Seaway Determined from Modeling Nd Isotopes P

Consequences of shoaling of the Central American Seaway determined from modeling Nd isotopes P. Sepulchre, T. Arsouze, Yannick Donnadieu, J.-C. Dutay, C. Jaramillo, J. Le Bras, E. Martin, C. Montes, A. Waite To cite this version: P. Sepulchre, T. Arsouze, Yannick Donnadieu, J.-C. Dutay, C. Jaramillo, et al.. Consequences of shoaling of the Central American Seaway determined from modeling Nd isotopes. Paleoceanography, American Geophysical Union, 2014, 29 (3), pp.176-189. 10.1002/2013PA002501. hal-02902783 HAL Id: hal-02902783 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02902783 Submitted on 5 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PUBLICATIONS Paleoceanography RESEARCH ARTICLE Consequences of shoaling of the Central American 10.1002/2013PA002501 Seaway determined from modeling Nd isotopes Key Points: P. Sepulchre1, T. Arsouze1,2, Y. Donnadieu1, J.-C. Dutay1, C. Jaramillo3, J. Le Bras1, E. Martin4, • Model/data comparison of epsilon Nd 5 4 suggests a shallow CAS during the C. Montes , and A. J. Waite Miocene 1 ’ • CAS throughflow depends -

Redalyc.VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY in CENTRAL

Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Lucas, Spencer G. VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY IN CENTRAL AMERICA: 30 YEARS OF PROGRESS Revista Geológica de América Central, , 2014, pp. 139-155 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45433963013 Revista Geológica de América Central, ISSN (Printed Version): 0256-7024 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative Revista Geológica de América Central, Número Especial 2014: 30 Aniversario: 139-155, 2014 DOI: 10.15517/rgac.v0i0.16576 ISSN: 0256-7024 VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY IN CENTRAL AMERICA: 30 YEARS OF PROGRESS PALEONTOLOGÍA DE VERTEBRADOS EN AMÉRICA CENTRAL: 30 AÑOS DE PROGRESO Spencer G. Lucas New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Road N. W., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87104 USA [email protected] (Recibido: 7/08/2014; aceptado: 10/10/2014) ABSTRACT: Vertebrate paleontology began in Central America in 1858 with the first published records, but the last 30 years have seen remarkable advances. These advances range from new localities, to new taxa to new analyses of diverse data. Central American vertebrate fossils represent all of the major taxonomic groups of vertebrates—fishes, amphibians, reptiles (especially turtles), birds and mammals (mostly xenarthrans, carnivores and ungulates)—but co- verage is very uneven, with many groups (especially small vertebrates) poorly represented. The vertebrate fossils of Central America have long played an important role in understanding the great American biotic interchange. -

The Age of Exploration (Also Called the Age of Discovery) Began in the 1400S and Continued Through the 1600S. It Was a Period Of

Activity 1 of 3 for NTI May 18 - 22 - Introduction to Exploration of North America Go to: https://www.ducksters.com/history/renaissance/age_of_exploration_and_discovery.php Click on the link above to read the article. There is a feature at the bottom that will allow you to have the text read to you, if you want. After you read the article, answer the questions below. You can highlight or bold your answers if completing electronically. I have copied the website text below if you need it. The Age of Exploration (also called the Age of Discovery) began in the 1400s and continued through the 1600s. It was a period of time when the European nations began exploring the world. They discovered new routes to India, much of the Far East, and the Americas. The Age of Exploration took place at the same time as the Renaissance. Why explore? Outfitting an expedition could be expensive and risky. Many ships never returned. So why did the Europeans want to explore? The simple answer is money. Although, some individual explorers wanted to gain fame or experience adventure, the main purpose of an expedition was to make money. How did expeditions make money? Expeditions made money primarily by discovering new trade routes for their nations. When the Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople in 1453, many existing trade routes to India and China were shut down. These trade routes were very valuable as they brought in expensive products such as spices and silk. New expeditions tried to discover oceangoing routes to India and the Far East. Some expeditions became rich by discovering gold and silver, such as the expeditions of the Spanish to the Americas. -

How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic Drifting Continents Open and Close Gateways Between Oceans and Shift Earth’S Climate

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v42n2/haug.html How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic Drifting continents open and close gateways between oceans and shift Earth’s climate By Gerald H. Haug, Geoforschungszentrum ly declined (with the anomalous excep- The supercontinent of Gondwana broke Potsdam (GFZ), Germany; Ralf Tiedemann, tion of the last century), and the planet as apart, separating into subsections that Forschungszentrum fur Marine Geowissen- schaften, Germany; and Lloyd D. Keigwin, a whole has steadily cooled. So why didn’t became Africa, India, Australia, South Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution both poles freeze at the same time? America, and Antarctica. Passageways The answer to the paradox lies in the opened between these new continents, he long lag time has always puzzled complex interplay among the continents, allowing oceans to flow between them. Tscientists: Why did Antarctica be- oceans, and atmosphere. Like pieces of a When Antarctica was finally severed come covered by massive ice sheets 34 puzzle, Earth’s moving tectonic plates have from the southern tip of South America million years ago, while the Arctic Ocean rearranged themselves on the surface of to create the Drake Passage, Antarctica acquired its ice cap only about 3 million the globe—shifting the configurations of became completely surrounded by the year ago? intervening oceans, altering ocean circula- Southern Ocean. The powerful Antarctic Since the end of the extremely warm, tion, and causing changes in climate. Circumpolar Current began to sweep all dinosaur-dominated Cretaceous Era 65 The development of ice sheets in the the way around the continent, effective- million years ago, heat-trapping green- Southern Hemisphere around 34 million ly isolating Antarctica from most of the house gases in the atmosphere have steadi- years ago seems fairly straightforward. -

100,000–11,000 Years Ago 75°

Copyrighted Material GREENLAND ICE SHEET 100,000–11,000 years ago 75° the spread of modern humans Berelekh 13,400–10,600 B ( E around the world during A ALASKA la R I ) SCANDINAVIAN n I e Bluefish Cave d N Arctic Circle G g 16,000 d ICE SHEET b G the ice age N i 25,000–10,000 r r i I d I b g e A R d Ice ) E n -fr SIBERIA a Dry Creek e l e B c All modern humans are descended from populations of ( o 35,000 Dyuktai Cvae 13,500 rri do 18,000 r Homo sapiens that lived in Africa c. 200,000 years ago. op LAURENTIDE en s ICE SHEET 1 Malaya Sya Around 60,000 years ago a small group of humans left 4 CORDILLERAN ,0 Cresswell 34,000 0 Africa and over the next 50,000 years its descendants 0 ICE SHEET – Crags 1 2 14,000 colonized all the world’s other continents except Antarctica, ,0 Wally’s Beach 0 Paviland Cave Mal’ta 0 EUROPE Mezhirich Mladecˇ in the process replacing all other human species. These 13,000–11,000 y 29,000 Denisova Cave 24,000 . 15,000 a 33,000 45,000 . Kostenki 41,000 migrations were aided by low sea levels during glaciations, Willendorf 40,000 Lascaux 41,700–39,500 which created land bridges linking islands and continents: Kennewick Cro Magnon 17,000 9,300 45° humans were able to reach most parts of the world on foot. Spirit 30,000 Cave Meadowcroft Altamira It was in this period of initial colonization of the globe that 10,600 Rockshelter 14,000 16,000 Lagar Velho Hintabayashi Tianyuan JAPAN modern racial characteristics evolved. -

Volcanic Growth 'Critical' to the Formation of Panama 5 February 2019, by Michael Bishop

Volcanic growth 'critical' to the formation of Panama 5 February 2019, by Michael Bishop the collision of two of Earth's tectonic plates—the South American Plate and the Caribbean Plate—which pushed underwater volcanoes up from the sea floor and eventually forced some areas above sea level. However, new geochemical and geochronological data taken from the Panama Canal and field investigation of old volcanoes in this area have provided evidence that there was significant volcanic activity taking place during a critical phase of the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama around 25 million years ago. The growth of volcanoes in the Panama Canal area is thought to have been particularly significant for the formation of the Isthmus because the Canal Credit: CC0 Public Domain was constructed in a shallow area of Panama, which is believed to have remained underwater for the major part of the geological history of the region. It is a thin strip of land whose creation kick-started one of the most significant geological events in the This suggests that the formation of the volcanoes past 60 million years. along the Canal could have played an important role in the rise of the Isthmus above sea level. Yet for scientists the exact process by which the Isthmus of Panama came into being still remains Scientists are keen to discover exactly how the largely contentious. Isthmus of Panama formed given its significant role in shaping both weather patterns and biodiversity In a new study published today in the journal across the world. Scientific Reports, scientists from Cardiff University have proposed that the Isthmus was born not Before a landmass existed between North and solely from tectonic process, but could have also South America, water had moved freely between largely benefited from the growth of volcanoes. -

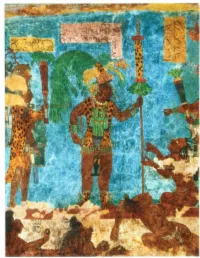

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields.