CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

KNOTLESS NETTING in AMERICA and OCEANIA T HE Question Of

116 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. s., 37, 1935 48. tcdbada'b stepson, stepdaughter, son or KNOTLESS NETTING IN AMERICA daughter of wife's brother or sis AND OCEANIA By D. S. DAVIDSON ter, son or daughter of husband's brother or sister: reciprocal to the HE question of trans-Pacific influences in American cultureshas been two preceding terms 49. tcdtsa'pa..:B T seriously debated for a number of years. Those who favor a trans step~grandfather, husband of oceanic movement have pointed out many resemblances and several grandparent's'sister 50. tCLlka 'yaBB striking similarities between certain culture traits of the New World and step-grandmother, wife of grand Oceania. The theory of a historical relationship between these appearances parent's brother 51. tcde'batsal' is based upon the hypothesis that independent invention and convergence step-grandchild, grandchild of speaker's wife's (or speaker's hus in development are not reasonable explanations either for the great number band's) brother or sister: recipro of resemblances or for the certain complexities found in the two areas. c~l to the two preceding terms The well-known objections to the trans-Pacific diffusion theory can 52. tsi.J.we'bats husband Or wife of grandchild of be summarized as follows: speaker or speaker's brother or 1. That many of the so-called similarities at best are only resemblances sister; term possibly reciprocal between very simple traits which might be independently invented or 53. tctlsxa'xaBll son-in-law or daughter-in-law of discovered. speaker's wife's brother or sister, 2. -

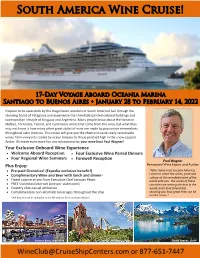

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Struggle for North America Prepare to Read

0120_wh09MODte_ch03s3_s.fm Page 120 Monday, June 4, 2007 10:26WH09MOD_se_CH03_S03_s.fm AM Page 120 Monday, April 9, 2007 10:44 AM Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION 3 Instruction 3 A Piece of the Past In 1867, a Canadian farmer of English Objectives descent was cutting logs on his property As you teach this section, keep students with his fourteen-year-old son. As they focused on the following objectives to help used their oxen to pull away a large log, a them answer the Section Focus Question piece of turf came up to reveal a round, and master core content. 3 yellow object. The elaborately engraved 3 object they found, dated 1603, was an ■ Explain why the colony of New France astrolabe that had belonged to French grew slowly. explorer Samuel de Champlain. This ■ Analyze the establishment and growth astrolabe was a piece of the story of the of the English colonies. European exploration of Canada and the A statue of Samuel de Champlain French-British rivalry that followed. ■ Understand why Europeans competed holding up an astrolabe overlooks Focus Question How did European for power in North America and how the Ottawa River in Canada (right). their struggle affected Native Ameri- Champlain’s astrolabe appears struggles for power shape the North cans. above. American continent? Struggle for North America Prepare to Read Objectives In the 1600s, France, the Netherlands, England, and Sweden Build Background Knowledge L3 • Explain why the colony of New France grew joined Spain in settling North America. North America did not Given what they know about the ancient slowly. -

The Diffusion of Maize to the Southwestern United States and Its Impact

PERSPECTIVE The diffusion of maize to the southwestern United States and its impact William L. Merrilla, Robert J. Hardb,1, Jonathan B. Mabryc, Gayle J. Fritzd, Karen R. Adamse, John R. Roneyf, and A. C. MacWilliamsg aDepartment of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37102, Washington, DC 20013-7012; bDepartment of Anthropology, One UTSA Circle, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78249; cHistoric Preservation Office, City of Tucson, P.O. Box 27210, Tucson, AZ 85726; dDepartment of Anthropology, Campus Box 1114, One Brookings Drive, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130; eCrow Canyon Archaeological Center, 23390 Road K, Cortez, CO 81321; fColinas Cultural Resource Consulting, 6100 North 4th Street, Private Mailbox #300, Albuquerque, NM 87107; and gDepartment of Archaeology, 2500 University Drive Northwest, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Edited by Linda S. Cordell, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, and approved October 30, 2009 (received for review June 22, 2009) Our understanding of the initial period of agriculture in the southwestern United States has been transformed by recent discoveries that establish the presence of maize there by 2100 cal. B.C. (calibrated calendrical years before the Christian era) and document the processes by which it was integrated into local foraging economies. Here we review archaeological, paleoecological, linguistic, and genetic data to evaluate the hypothesis that Proto-Uto-Aztecan (PUA) farmers migrating from a homeland in Mesoamerica intro- duced maize agriculture to the region. We conclude that this hypothesis is untenable and that the available data indicate instead a Great Basin homeland for the PUA, the breakup of this speech community into northern and southern divisions Ϸ6900 cal. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information

Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information Updated August 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46225 SUMMARY R46225 Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Statistical August 5, 2021 Information Carla Y. Davis-Castro This report provides statistical information on Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Data and Research Librarian findings vary, sometimes greatly, on all topics covered in this report, including populations and languages, socioeconomic data, land and natural resources, human rights and international legal conventions. For example the figure below shows four estimates for the Indigenous population of Latin America ranging from 41.8 million to 53.4 million. The statistics vary depending on the source methodology, changes in national censuses, the number of countries covered, and the years examined. Indigenous Population and Percentage of General Population of Latin America Sources: Graphic created by CRS using the World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab with webpage last updated in July 2021; ECLAC and FILAC’s 2020 Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina - Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: tensiones y desafíos desde una perspectiva territorial; the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank’s (WB) 2015 Indigenous Latin America in the twenty-first century: the first decade; and ECLAC’s 2014 Guaranteeing Indigenous people’s rights in Latin America: Progress in the past decade and remaining challenges. Notes: The World Bank’s LAC Equity Lab -

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: an Institutional Account*

Collective Identity in the Andean Community: An Institutional Account* Identidad colectiva en la comunidad andina: una aproximación institucional Germán Camilo Prieto** Recibido: 15/05/2015 Aprobado: 14/07/2015 Disponible en línea: 30/11/2015 Abstract Resumen This article assesses the ways in which regional Este artículo evalúa la forma en que las institu- institutions, understood as norms and institu- ciones regionales, entendidas como las normas y tional bodies, contribute to the formation of los órganos institucionales, contribuyen a la for- collective identity in the Andean Community mación de identidad colectiva en la Comunidad (AC). Departing from the previous existence Andina (CAN). Partiendo de la existencia previa of an Andean identity, grounded on historical de una identidad andina, basada en elementos and cultural issues, the paper takes three case históricos y culturales, el artículo toma tres studies to show the terms in which regional estudios de caso para mostrar los términos en institutions contribute to the formation of three que las instituciones regionales contribuyen a la dimensions of collective identity in the AC. formación de tres dimensiones de la identidad Namely, these are the cultural, ideological, and colectiva en la CAN, a saber: la dimensión cul- inter-group dimensions. The paper shows that tural, la ideológica y la intergrupal. Este trabajo although the ideas held about an Andean collec- muestra que aunque las ideas de una identidad tive identity by state representatives and Andean colectiva Andina que tienen los funcionarios doi:10.11144/Javeriana.papo20-2.ciac * Artículo de investigación. The present article is based on a paper presented at the XXII IPSA World Congress, Madrid 2012, at the Panel “Theorising the Role of Identity in the Unfolding of Regionalism: Comparative Perspectives”. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region

Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Programme developed by International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations Co-editors Gustavo Guerra-García Kristen Sample Javier Alarcón Cervera Vanessa Cartaya José Luis Exeni Pedro Francke Haydée García Velásquez Claudia Giménez Francisco Herrero Carlos Meléndez Guerrero Gabriele Merz Gabriel Murillo Luís Javier Orjuela Michel Rowland García Alfredo Sarmiento Gómez Politics and Poverty in the Andean Region Policy Summary: Key Findings and Recommendations International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008 Asociación Civil Transparencia 2008 International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA and Asociación Civil Transparencia, its Board or its Council members. AAAAAA Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: International IDEA aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa SE 103 34 Stockholm aaaaaaaiaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Sweden aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa International