KNOTLESS NETTING in AMERICA and OCEANIA T HE Question Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

The Birds of Gag Island, Western Papuan Islands, Indonesia

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.23(2).2006.115-132 [<ecords o{ the rVcstCrJJ Australian Museum 23: 115~ n2 (2006). The birds of Gag Island, Western Papuan islands, Indonesia R.E. Johnstone Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welsh pool DC Western Australia 6'1S6 Abstract This report is based mainly on data gathered during a biological survey of C;ag Island by a joint Western Australian Museum, Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense and Herbarium Bogoriense expedition in July 1'197. A total of 70 species of bird have been recorded for Gag Island and a number of these represent new island and/or Raja Ampat Archipelago records. Relative abundance, status, local distribution and habitat preferences found for each species arc described, extralimital range is outlined and notes on taxonomv are also given. No endemic birds were recorded for Gag Island but a number of species show significant morphological variation from other island forms and may prove to be distinct taxonomically. INTRODUCTION undergo geographic variation for taxonon,ic, Gag Island (0025'S, 129 U 53'E) is one of the Western morphological and genetic studies. The Papuan or Raja Ampat Islands, lying just off the annotated checklist provided covers every Vogelkop of Irian Jaya, between New Guinea and species recorded, both historically and during Halmahera, Indonesia. These islands include (from this survey. north to south) Sayang, Kawe, Waigeo, Gebe, Gag, In the annotated list I summarise for each species Gam, Batanta, Salawati, Kofiau, Misool and a its relative abundance (whether it is very common, number of small islands (Figure 1). Gag Island is common, moderately common, uncommon, scarce separated from its nearest neighbours Gebe Island or rare), whether it feeds alone or in groups, status to the north~west, and Batangpele Island to the (a judgement on whether it is a vagrant, visitor or north-east, by about 40 km of relatively deep sea. -

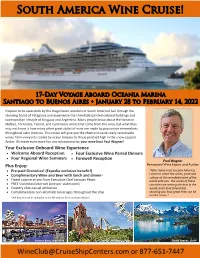

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." the Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 169–182. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 09:12 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 Africa in Oceania Māui and Legba Hone Taare Tikao, an Ngāi Tahu scholar involved in Te Kotahitanga, the Māori Parliament movement of the late nineteenth century, puts the pieces together: Māui must have visited Africa in one of his epic journeys.1 For once upon a time Māui had turned a thief called Irawaru into a dog, and since then some Māori have considered the dog to be their tuākana (elder sibling). In the 1830s a trading ship from South Africa arrives at Otago harbour. On board is a strange animal that the sailors call a monkey but that the local rangatira (chiefs) recognize to be, in fact, Irawaru. They make speeches of welcome to their elder brother. It is 1924 and the prophet Rātana visits the land that Māui had trodden on so long ago. He finds a Zulu chief driving a rickshaw. He brings the evidence of this debasement back to the children of Tāne/ Māui as a timely warning as to their own standing in the settler state of New Zealand. It is 1969 and Henderson Tapela, president of the African Student’s Association in Aotearoa NZ, reminds the children of Tāne/Māui about their deep-seated relationship with the children of Legba. -

European Collection 2015

European Collection 2015 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN & THE RIVIERAS EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN & GREEK ISLES NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES CONTINENTAL EUROPE CONTENTS 2 EXPERIENCE 96 TRANSOCEANIC VOYAGES The OlifeTM 104 gRAND VOYAGES 16 TASTE The Finest Cuisine at Sea 114 EXPLORE ASHORE Shore Excursion Collections & Land Tour Series 28 VALUE Best Value in Upscale Cruising 123 HOTEL PROGRAMS Pre- & Post-Cruise Hotel Programs 32 OcEANIA CLUB 126 SUITES & STATEROOMS 34 DESTINATION SPECIALISTS Culinary Discovery ToursTM & New Ports of Call 136 DECK PLANS 42 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN 140 PROGRAMS & INFORMATION & THE RIVIERAS Travel Protection & Air Program Details 62 EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN 142 CRUISE CALENDAR & GREEK ISLES 144 EXPERIENCE OcEANIACRUISES.COM 74 NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES 145 GENERAL INFORMATION Oceania Club Terms & Conditions 90 CONTINENTAL EUROPE ON THE COVER Scottish kilts originate back to the 16th century and were traditionally worn as full length garments by Gaelic-speaking male Highlanders of northern Scotland POINTS OF DISTINCTION n FREE AIRFARE* on every voyage n Mid-size, elegant ships catering to just 684 or 1,250 guests n Finest cuisine at sea, served in a variety of distinctive open-seating Europe Collection restaurants, at no additional charge n Gourmet culinary program crafted 2015 by world-renowned Master Chef Jacques Pépin THE MAGIC OF THE OLD WORLD | When millenniums of history and great works n of art meet captivating cultures and generous smiles, you know you’ve arrived in Europe. Spectacular port-intensive itineraries featuring overnight visits and extended From Michelangelo’s David in Florence to Rembrandt’s masterpieces in Amsterdam, you evening port stays will be awed and inspired. Stand on the Acropolis in Athens or explore the gilded czar palaces in St. -

Asia's Rise in the New World Trade Order

GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Authors Dr. Cora Jungbluth (Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh), Dr. Rahel Aichele (ifo, München), Prof. Gabriel Felbermayr, PhD (ifo and LMU, München) GED Study Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order The Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements on Asian Countries Part 2 of the GED Study Series: Effects of Mega-Regional Trade Agreements Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Table of contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction: Mega-regionals and the new world trade order 6 2. Asia in world trade: A look at the “noodle bowl” 10 3. Mega-regionals in the Asia-Pacific region and their effects on Asian countries 14 3.1 The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): The United States’ “pivot to Asia” in trade 14 3.2 The Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP): An inclusive alternative? 16 3.3 The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The ASEAN initiative 18 4. Case studies 20 4.1 China: The world’s leading trading nation need not fear the TPP 20 4.2 Malaysia: The “Asian Tiger Cub” profits from deeper transpacific integration 22 5. Parallel scenarios: Asian-Pacific trade deals as counterweight to the TTIP 25 6. Conclusion: Asia as the driver for trade integration in the 21st century 28 Appendix 30 Bibliography 30 List of abbreviations 34 List of figures 35 List of tables 35 List of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 36 Links to the fact sheets of the 20 Asian countries included in our analysis 37 About the authors 39 Imprint 39 4 Asia’s Rise in the New World Trade Order Executive summary Asia is one of the most dynamic regions in the world and the FTAAP, according to our calculations the RCEP also has the potential to become the key region in world trade has positive economic effects for most countries in Asia, in the 21st century. -

Two Centuries of International Migration

IZA DP No. 7866 Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Timothy J. Hatton December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Two Centuries of International Migration Joseph P. Ferrie Northwestern University Timothy J. Hatton University of Essex, Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7866 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

On the Limits of Indonesia

CHAPTER ONE On the Limits of Indonesia ON July 2, 1998, a little over a month after the resignation of Indonesia’s President Suharto, two young men climbed to the top of a water tower in the heart of Biak City and raised the Morning Star flag. Along with similar flags flown in municipalities throughout the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya, the flag raised in the capital of Biak-Numfor signaled a demand for the political independence of West Papua, an imagined nation comprising the western half of New Guinea, a resource-rich territory just short of Indonesia’s east- ernmost frontier. During the thirty-two years that Suharto held office, ruling through a combination of patronage, terror, and manufactured consent, the military had little patience for such demonstrations. The flags raised by Pap- uan separatists never flew for long; they were lowered by soldiers who shot “security disrupters” on sight.1 Undertaken at the dawn of Indonesia’s new era reformasi (era of reform), the Biak flag raising lasted for four days. By noon of the first day, a large crowd of supporters had gathered under the water tower, where they listened to speeches and prayers, and sang and danced to Papuan nationalist songs. By afternoon, their numbers had grown to the point where they were able to repulse an attack by the regency police, who stormed the site in an effort to take down the flag. Over the next three days, the protesters managed to seal off a dozen square blocks of the city, creating a small zone of West Papuan sovereignty adjoining the regency’s main market and port. -

Conerence Entitled "Understanding Population Change: *United States

AUTHOR Roseman-, Curti And Others TITLE Population Redistribution in the Mi wes INSTITUTION North 'central Regional Center for Ru al Development Ames,. Iowa. 1PONS -AGENgY --Department-of Agriculture, WashingtoA C. PUB DATE Nay 81 . NOTE 22BR.: 'Papers were ofiginally presented at a conerence entitled "Understanding Population Change: Issuei and Consequences of Population Redistribution ' in the Midwest" (Champaign, IL, Birch 12, 1979). EDPS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Decentraliiation: *Demography: Employment Patterns: Geography: Indubtry: Land Use: Migrants: *Migration' Patterns: Politics: *Population Distribution: Public Policy: Research Needs: *Rural Ardasi *Urban to Rural Migtation IDENTIFI *United States (Midwest ABSTRACT The-ninechapter0-in the book f4dus on the 1970s' metropolitan to-4nOnmetropolitan migration stream and address both population -patterns and`'-prooesses and the impacts and policy issues associated with the result-in-q, popUlation'redistribution in the Midwest. Peter A. Morrison places the Midwest in the national context of changing population structure and redistribution. John R Borchert traces the,Ilistorical and geographic forCeS which have shaped the 'current'patterts.:CalvinL.. Bealeand Glenn V. Fuguittfocus. on deiographicaspedtt Mf,redistribution'in.W Midwest. Ralph R. 'lifter' and Richard W. Buxbaum place Midwest trends in a policy context. Andrew J. Sofranko, James D. Williams, and prederick C. Fliegel disduss. a survey offecent migrantS to fastzgrowing Midwest' nonmetropolitan areas. RiehardLonsdale documents the decentralization trend in manufacturing employment and. its role, in population redistribution. David Bdtry-examinesthe:significance-of land cOnverSton:from rural to 'urban uses. Alvin D. Sokolov addresses - the localpolitical implications\of recent small town growth. ,Laurence S. ROsen.outlines and analyzes methods and data needed for population pitolectiOns.-- fAuthOt,SEI --_*****#****** ********. -

BREAKDOWN of SUB-REGIONS Americas

BREAKDOWN OF SUB-REGIONS Americas Atlantic Islands and Central and Canada Eastern US Latin America Southwest US Argentina Atlantic Canada Kansas City Boston Atlantic Islands British Columbia Nebraska Hartford Brazil A Canadian Prairies Oklahoma Maine Brazil B Montreal & Quebec Southwest US A New York A Central America Toronto Southwest US B New York B Chile St. Louis Philadelphia Colombia Pittsburgh Mexico Washington DC Peru Western New York Uruguay Midwest US Southeastern US Western US Chicago Florida Colorado Cleveland Greater Tennessee Desert US Indianapolis Louisville Hawaii Iowa Mid-South US Idaho Madison North Carolina Los Angeles Milwaukee Southern Classic New Mexico Minnesota Virginia Northern California Southern Ohio Orange County West Michigan Portland Salt Lake San Diego Seattle Spokane Asia Pacific Oceania Eastern Asia Southeastern Asia Southern Asia Brisbane Beijing Cambodia Bangladesh Melbourne Chengdu Indonesia India A New Zealand Hong Kong Malaysia India B Perth Japan Philippines India C Sydney Korea Singapore Nepal Mongolia Thailand Pakistan Shanghai Vietnam Sri Lanka Shenzhen A Shenzhen B Taiwan Europe, Middle East, and Africa Sub-Saharan Africa Eastern Europe Northern Europe Southern Europe Ethiopia Bulgaria Denmark & Norway Croatia Ghana Czech Republic Finland Cyprus Kenya Hungary Ireland Greece Mauritius Kazakhstan Sweden Israel Nigeria A Poland A Istanbul Nigeria B Poland B Italy Rwanda Romania Portugal South Africa Russia A Serbia Tanzania Russia B Slovenia Uganda Slovakia Spain Zimbabwe Ukraine A Ukraine B Middle East and Western Europe North Africa Austria Bahrain Benelux Doha France Egypt Germany Emirates Switzerland Jordan Kuwait Lebanon Morocco Oman Saudi Arabia . -

Explorers of Africa

Explorers of Africa Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) Portugal Goals of exploration: establish a Christian empire in western Africa find new sources of gold create maps of the African coast Trips funded by Henry the Navigator led to more Impact: exploration of western Africa Bartolomeu Días (1450-1500) Portugal Rounded the southernmost tip of Africa in 1488 Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Impact: Led the Portuguese closer to discovering a water route to Asia Vasco da Gama (1460s-1524) Portugal Rounded the southernmost tip of Africa; Reached India in 1498 Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Found a water route to Asia and brought back Impact: jewels and spices, which encouraged further exploration Explorers of the Caribbean Christopher Columbus (1450-1506) Spain In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue (He sailed again in 1493, 1498, and 1502) Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia Discovered the New World and led to Impact: exploration of the Americas Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) Spain Discovered the Pacific Ocean and the Isthmus of Panama in 1513 Goal of exploration: further exploration of the New World Discovered the Pacific Ocean and a new Impact: passage for exploration Explorers of South America Ferdinand Magellan Spain (1480-1521) Magellan's ships completed the first known circumnavigation of the globe. Goal of exploration: find a water route to Asia across the Pacific Discovered a new passage between the Impact: Atlantic and Pacific Oceans Francisco Pizarro Spain (1470s-1541) Conquered