The Eurasian Landbridge: Implications of Linking East Asia and Europe by Rail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

Publication: BELT and ROAD INITIATIVE (BRI)

“CGSS is a Non-Profit Institution with a mission to help improve policy and decision-making through analysis and research” Copyright © Center for Global & Strategic Studies (CGSS) All rights reserved Printed in Pakistan Published in April, 2017 ISBN 978 969 7733 05 7 Please do not disseminate, distribute or reproduce, in whole or part, this report without prior consent of CGSS CGSS Center for Global & Strategic Studies, Islamabad 3rd Floor, 1-E, Ali Plaza, Jinnah Avenue, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: +92-51-8319682 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cgss.com.pk Abstract Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is a massive project which can be termed as a revival of the Ancient Silk Road in order to materialize the Prophecy of Asian Century through the economic expansion and infrastructural build-up by China. The project comprises of two major components that are: 21st Century Maritime Silk Route (MSR) and Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) which is further distributed in six overland economic corridors where China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one significant corridor. The project holds massive importance for China in particular and all the other stakeholders in general and will provide enormous opportunity for the socio-economic as well as the infrastructural development of many countries across the globe. The rationale behind China’s massive investment in this project is to attain global domination through geopolitical expansions. China’s economic activities and investment are directed to the promotion of global trade. Although the commencement of the project met with skeptical views as for few specific countries, it is China’s strategic policy to upsurge and enhance its military and economic presence in the World especially in the Indian Ocean and emerge as an economic giant by replacing USA’s superpower status. -

The Less-Splendid Isolation of the South American Continent

news and update ISSN 1948-6596 commentary The less-splendid isolation of the South American continent Only few biogeographic scenarios capture the im- lower Central America (Costa Rica) and South agination as much as the closure of the Isthmus of America (northern Colombia), and that some Panama. The establishment of this connection snapping shrimp populations were already split ended the “splendid isolation” of the South Amer- long before the Isthmus had finally closed (most ican continent (Simpson 1980), a continent that between 7–10 mya but some >15 mya). Next to had been unconnected to any other land mass for this, several papers showed that plants also mi- over 50 million years. When the Isthmus rose out grated between North and South America prior to of the water some 3 million years ago (mya) the the closure of the Isthmus (e.g., Erkens et al. 2007, Great American Biotic Interchange started. Since Bacon et al. 2013), although for plants it is difficult terrestrial biotic interchange was no longer to rule out that this happened via long-distance blocked by the Central American Seaway, dispersal. Thus, the new findings of Montes and (asymmetrical) invasion of taxa across this new colleagues fit much better with a wealth of evi- land bridge transformed biodiversity in North as dence from the biological realm that has been well as South America (Leigh et al. 2014). Or so amassed over the last years, than the old model of the story goes. a relatively rapid rise of the Isthmus. A recent paper by Montes et al. (2015) casts If the land-bridge was available much earli- further serious doubt on this scenario from a geo- er to many terrestrial organisms, the question that logical perspective. -

Day 2 Social Studies

Day 2 Social Studies - Read the article "The Earliest Americans" and complete the Build Your Map Skills page and Extinct Animals of North America page. Language Arts - Draw a self-portrait of yourself in the center of a piece of paper. Write a simile that describes parts of yourself. You must have at least 6 similes. For example, I would point to my hair and say "My hair is as red as a tomato." Reminder: a simile is a comparison of two things using like or as. Science- Help! My rose plant is no longer able to carry out photosynthesis, meaning that it can't make its own food anymore. Create an alternate system to keep my rose plant alive . Develop a new system and parts of the plant that will help it be able to obtain nutrients using pictures and descriptions. Math - Look through old magazines and newspapers for 15 numbers that have decimals. Cut out and paste the numbers onto paper in least to greatest order. Use the cut-out numbers to make up five word problems dealing with addition, subtraction, or multiplication. Make a separate key for the problems. Staple the problems and the key to the construction paper. he Earliest Americans. f \ \ Did you ever wonder in what kind of homes the first Americans lived or what kind of food they ate? Anthropologists and archaeologists devote their lives to answering such questions. Anthropologists are scientists who study all aspects of human beings, such as their society and culture. Archaeologists are scientists who use physical evidence and artifacts to analyze human cultures. -

China's Belt and Road: a Game Changer?

Alessia Amighini Offi cially announced by Xi Jinping But it also reaches out to the Middle in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative East as well as East and North (BRI) has since become the Africa, a truly strategic area where centrepiece of China’s economic the Belt joins the Road. Europe, the diplomacy. It is a commitment end-point of the New Silk Roads, to ease bottlenecks to Eurasian both by land and by sea, is the trade by improving and building ultimate geographic destination and networks of connectivity across political partner in the BRI. Central and Western Asia, where the BRI aims to act as a bond for This report provides an in-depth the projects of regional cooperation analysis of the BRI, its logic, rationale and integration already in progress and implications for international in Southern Asia. economic and political relations. China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? China’s Alessia Amighini EDITED BY ALESSIA AMIGHINI Senior Associate Research Fellow and Co-Head of Asia Programme at ISPI. Associate Professor of CHINA’S BELT AND ROAD: Economics at the University of Piemonte Orientale and Catholic University of Milan. A GAME CHANGER? INTRODUCTION BY PAOLO MAGRI ISBN 978-88-99647-61-2 Euro 9,90 China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? Edited by Alessia Amighini ISBN 978-88-99647-61-2 ISBN (pdf) 978-88-99647-62-9 ISBN (ePub) 978-88-99647-63-6 ISBN (kindle) 978-88-99647-64-3 DOI 10.19201/ispichinasbelt ©2017 Edizioni Epoké - ISPI First edition: 2017 Edizioni Epoké. -

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape │ 3 China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development strategy aims to build connectivity and co-operation across six main economic corridors encompassing China and: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasian countries; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; other countries of the Indian sub-continent; and Indochina. Asia needs USD 26 trillion in infrastructure investment to 2030 (Asian Development Bank, 2017), and China can certainly help to provide some of this. Its investments, by building infrastructure, have positive impacts on countries involved. Mutual benefit is a feature of the BRI which will also help to develop markets for China’s products in the long term and to alleviate industrial excess capacity in the short term. The BRI prioritises hardware (infrastructure) and funding first. This report explores and quantifies parts of the BRI strategy, the impact on other BRI-participating economies and some of the implications for OECD countries. It reproduces Chapter 2 from the 2018 edition of the OECD Business and Financial Outlook. 1. Introduction The world has a large infrastructure gap constraining trade, openness and future prosperity. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are working hard to help close this gap. Most recently China has commenced a major global effort to bolster this trend, a plan known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China and economies that have signed co-operation agreements with China on the BRI (henceforth BRI-participating economies1) have been rising as a share of the world economy. -

China's Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chapter 3

china’s eurasian century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative Nadège Rolland Chapter 3 Drivers of the Belt and Road Initiative This is a preview chapter from China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. To purchase the monograph in which this chapter appears, visit <http://www.nbr.org> or contact <[email protected]>. © 2017 The National Bureau of Asian Research Chapter 3 Drivers of the Belt and Road Initiative In less than three years, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become the defining concept of China’s foreign policy and is now omnipresent in official rhetoric. It has established a general direction for the country’s efforts to build an interconnected, integrated Eurasian continent before 2050. Judging by the importance that the leadership has given the concept, and the quantity of financial, diplomatic, and intellectual resources that have been devoted to it, arguing that BRI is just an empty shell or vacuous political slogan has become increasingly difficult. Its paramount importance for the core leadership is also hard to deny. What is so crucial about the initiative that the vital energies of the entire country have been mobilized to give it the best chances of succeeding? Why is Beijing so eager to invest billions of dollars in Eurasia’s infrastructure connectivity? What are the drivers behind BRI and what are its goals? A first partial answer to these questions can be found in Xi Jinping’s speeches. In several instances, he has argued that -

100,000–11,000 Years Ago 75°

Copyrighted Material GREENLAND ICE SHEET 100,000–11,000 years ago 75° the spread of modern humans Berelekh 13,400–10,600 B ( E around the world during A ALASKA la R I ) SCANDINAVIAN n I e Bluefish Cave d N Arctic Circle G g 16,000 d ICE SHEET b G the ice age N i 25,000–10,000 r r i I d I b g e A R d Ice ) E n -fr SIBERIA a Dry Creek e l e B c All modern humans are descended from populations of ( o 35,000 Dyuktai Cvae 13,500 rri do 18,000 r Homo sapiens that lived in Africa c. 200,000 years ago. op LAURENTIDE en s ICE SHEET 1 Malaya Sya Around 60,000 years ago a small group of humans left 4 CORDILLERAN ,0 Cresswell 34,000 0 Africa and over the next 50,000 years its descendants 0 ICE SHEET – Crags 1 2 14,000 colonized all the world’s other continents except Antarctica, ,0 Wally’s Beach 0 Paviland Cave Mal’ta 0 EUROPE Mezhirich Mladecˇ in the process replacing all other human species. These 13,000–11,000 y 29,000 Denisova Cave 24,000 . 15,000 a 33,000 45,000 . Kostenki 41,000 migrations were aided by low sea levels during glaciations, Willendorf 40,000 Lascaux 41,700–39,500 which created land bridges linking islands and continents: Kennewick Cro Magnon 17,000 9,300 45° humans were able to reach most parts of the world on foot. Spirit 30,000 Cave Meadowcroft Altamira It was in this period of initial colonization of the globe that 10,600 Rockshelter 14,000 16,000 Lagar Velho Hintabayashi Tianyuan JAPAN modern racial characteristics evolved. -

Silk Road 2.0: US Strategy Toward China’S Belt and Road Initiative

Silk Road 2.0: US Strategy toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative Gal Luft Foreword by Joseph S. Nye, Jr. REVIVING THE SILK ROAD Announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the Silk Road in infrastructure projects including railways and power grids in central, Initiative, also known as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, aims to invest west, and southern Asia, as well as Africa and Europe. Silk Road 2.0 US Strategy toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative Atlantic Council Strategy Paper No. 11 © 2017 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-406-3 Cover art credit: Marco Polo’s caravan, from the Catalan Atlas, ca. 1375 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council, its partners, and funders do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s particular conclusions. October 2017 Atlantic Council Strategy Papers Editorial Board Executive Editors Mr. Frederick Kempe Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev Editor-in-Chief Mr. Barry Pavel Managing Editor Dr. Mathew Burrows Table of Contents -

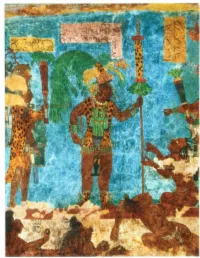

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

The New Eurasian Land Bridge

The New Eurasian Land Bridge Opportunities for China, Europe, and Central Asia Gabor Debreczeni MA in International Development and International Economics, Class of 2015 Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies ©John Cobb ABSTRACT This article evaluates the present and considers the future of the intermediary role of Central Asia in overland trade routes from China to Europe. Focusing primarily on technical and pragmatic issues, it discusses the advantages and costs of potential freight modes and trade routes from China to Europe, finding that rail freight already operates successfully and at high efficiency via Central Asia, albeit at a small scale. Central Asian countries play a successful economic role in the overland trade, but could further benefit if they took part in, rather than just facilitated, China-Europe trade. China and Europe benefit from faster and cheaper trade with each other, and would further benefit from the inclusion of nations in between for either their import demand or their potential development as low-cost manufacturers. On the other hand, Russia’s policy regarding overland trade is driven by the opportunity of continued re-integration with Central Asian nations in the name of facilitated trade. The first section discusses the advantages and costs of potential freight modes and trade routes from China to Europe. The second section describes the Central Asian route’s emergence and the current state of its freight operations. The third section considers the long-term outlook of the route and the challenges of high-speed upgrades mooted by China. The fourth section analyzes Central Asian economies’ current roles in the trade occurring between China and Europe on the Central Asian trade route, as well as potential opportunities for their further engagement with China-Europe trade, while the last section discusses risks for the route’s future importance and growth. -

Beringia Vocabulary

Beringia Vocabulary 1) artifact--an object made by humans, such as a tool The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass th2a) t acrocnhnaecotloegdy A--sthiae astnudd yN oofr thhis Atomrice raicnad 1pr0e,h0i0s0to-r2ic5 ,000 years ago. Duringp tehoisp lteime, glaciers up to two miles thick covered large parts of North America, Europe and Asia. T3h)e ppaelerioondt owloagsy -c-athllee dst uthdey Pofl eeiasrtloyc leifen eb yIc loeo Akigneg. aSt ome very dry areas weforess iiclse-free during this time. Much of the Earth's water was locked up in the glaciers. Because of th4i)s psereah ilsetvoerilc d--rao pppeeridod s oigfn timficea bnetlfyo, ruep w troit t3e0n0 o fre et! Some areas that are now urencdoerrd weda theisr tboerycame dry land. The result was an intermittent land bridge stretching between 5) fossil--the remains, impression, imprint or bone of the two cao nlivtiinge nthtsin ugnder the present day Bering and Chukchi Seas. Scientists believe that Beringia was at its w6id) e esxtt ipnoctin--ta a sbpoeuctie 1s5 t,h0a0t 0h ayse adriesd a oguot., Anolt hloonuggehr icna lled a "bridge," the leaxnisdt ewnacse really a broad, grassy plain, which many animals stopped to feed on. 7) Pleistocene-- 2 million to 10,000 years ago Beringia The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass 1t0h,a0t0 c0o tnon 2e5c,t0e0d0 A yseiar asn adg No,o drtuhr inAgm teheri cpae r1io0d,0 k0n0o-w2n5 ,a0s0 0th e Pyleeaisrtso caegnoe. IDceu rAingge ,t hgilsa ctiiemrse ,u gpl atoc itewros mupile tso tthwicok mcoilveesr ethdi clakr ge pcaorvtse oref dN olartrhg eA mpaerrtisc ao, fE Nuorortphe ,A amned rAicsaia, Eaundro mpeu cahn odf Athseia e.a rth's wTahter pwearsio ldo cwkaeds ucpa lilne dth teh eg laPcleieirsst.o Tcheen es eIcae le Avegle d.