The New Eurasian Land Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publication: BELT and ROAD INITIATIVE (BRI)

“CGSS is a Non-Profit Institution with a mission to help improve policy and decision-making through analysis and research” Copyright © Center for Global & Strategic Studies (CGSS) All rights reserved Printed in Pakistan Published in April, 2017 ISBN 978 969 7733 05 7 Please do not disseminate, distribute or reproduce, in whole or part, this report without prior consent of CGSS CGSS Center for Global & Strategic Studies, Islamabad 3rd Floor, 1-E, Ali Plaza, Jinnah Avenue, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: +92-51-8319682 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cgss.com.pk Abstract Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is a massive project which can be termed as a revival of the Ancient Silk Road in order to materialize the Prophecy of Asian Century through the economic expansion and infrastructural build-up by China. The project comprises of two major components that are: 21st Century Maritime Silk Route (MSR) and Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) which is further distributed in six overland economic corridors where China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is one significant corridor. The project holds massive importance for China in particular and all the other stakeholders in general and will provide enormous opportunity for the socio-economic as well as the infrastructural development of many countries across the globe. The rationale behind China’s massive investment in this project is to attain global domination through geopolitical expansions. China’s economic activities and investment are directed to the promotion of global trade. Although the commencement of the project met with skeptical views as for few specific countries, it is China’s strategic policy to upsurge and enhance its military and economic presence in the World especially in the Indian Ocean and emerge as an economic giant by replacing USA’s superpower status. -

The New Silk Road, Part II: Implications for Europe

The New Silk Road, part II: implications for Europe Through the New Silk Road (NSR) initiative, China increasingly invests in building and modernizing Stephan Barisitz, overland and maritime infrastructures with a view to enhancing the overall connectivity between Alice Radzyner1 China and Europe. The NSR runs through a number of Eurasian emerging markets and extends out to Southeastern Europe (SEE), where Chinese investments include the modernization of ports and highspeed rail and road projects to speed up the transport of goods between China and Europe (e.g. port of Piraeus, rail connection to Budapest). Participation in the NSR will probably stimulate SEE’s economic expansion and may even contribute to overcoming its traditional peripheral position in Europe. Ideally, SEE will play a role in catalyzing a deepening of China-EU economic relations, e.g. by facilitating European exports to China and other countries along NSR trajectories, which would boost growth in Europe more widely. In the long run, these developments might also influence the EU’s political and economic positioning on a global scale. JEL classification: F15, F34, N75, R12, R42 Keywords: New Silk Road, One Belt, One Road, connectivity, trade infrastructure, economic corridors, regional policy, Southeastern Europe (SEE), China, EU-China relations, China-EU relations, China-EU trade, EU-China trade, EU candidate countries Introduction This paper is the second of a set of twin studies on the New Silk Road (NSR).2 While part I shows how the NSR is developing through the growing number of Chinese projects in several Eurasian and Asian emerging markets, part II focuses on Southeastern Europe (SEE), where Chinese investments seem to be paving the way toward the heart of the continent. -

The New Silk Road “China – Europe Landbridge”

THE NEW SILK ROAD “CHINA – EUROPE LANDBRIDGE” David Brice International Railway Consultant PAST PRESENT AND FUTURE Rail links have operated between China and Europe since 1916 There has been massive trade growth between China and Europe over the past 20 years The trade is dominated by shipping Only 2% of this trade is moved by land Ambition exists to triple rail traffic over the next 20 years The Present Routes • Trans Siberian route • Trans Kazakhstan route The Present Routes Trans Siberian Route • Completed in 1916 • Distance to Polish Border 9288 km • Countries transited to Europe: Mongolia / Russia / Belarus / Poland / Germany • Double track and electrified beyond Mongolia • Route currently full but Russians now spending $43bn to increase capacity Trans Kazakhstan Route • Completed in 1994 • Distance: 10 214 km to Hamburg • Countries transited to Europe: Kazakhstan / Russia / Belorus / Poland / Germany • Eastern Section: currently single track with diesel power: remainder double track and electrified Current Strategic Partners operating throughout services United Transport & Logistics Co (Russia/Kazakhstan/Belarus) Hewlett Packard DB Schenker DHL Global Forwarding UPS Political Aspects • Countries transited • Recent political changes • Current contingent risks China – Asia Rapid Build-Up of Rail Routes • Build-up of new rail routes between China and Asia • Druzba route: opened in 1994 • Zhetigen-Korgas route: opened in 2013 • Uzbek-Caspian route: planning in hand • Kashgar-Dushanbe-Afghan-Turkey: in perspective • Marmaray -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

China's Belt and Road: a Game Changer?

Alessia Amighini Offi cially announced by Xi Jinping But it also reaches out to the Middle in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative East as well as East and North (BRI) has since become the Africa, a truly strategic area where centrepiece of China’s economic the Belt joins the Road. Europe, the diplomacy. It is a commitment end-point of the New Silk Roads, to ease bottlenecks to Eurasian both by land and by sea, is the trade by improving and building ultimate geographic destination and networks of connectivity across political partner in the BRI. Central and Western Asia, where the BRI aims to act as a bond for This report provides an in-depth the projects of regional cooperation analysis of the BRI, its logic, rationale and integration already in progress and implications for international in Southern Asia. economic and political relations. China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? China’s Alessia Amighini EDITED BY ALESSIA AMIGHINI Senior Associate Research Fellow and Co-Head of Asia Programme at ISPI. Associate Professor of CHINA’S BELT AND ROAD: Economics at the University of Piemonte Orientale and Catholic University of Milan. A GAME CHANGER? INTRODUCTION BY PAOLO MAGRI ISBN 978-88-99647-61-2 Euro 9,90 China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? Edited by Alessia Amighini ISBN 978-88-99647-61-2 ISBN (pdf) 978-88-99647-62-9 ISBN (ePub) 978-88-99647-63-6 ISBN (kindle) 978-88-99647-64-3 DOI 10.19201/ispichinasbelt ©2017 Edizioni Epoké - ISPI First edition: 2017 Edizioni Epoké. -

Security and Economy on the Belt and Road: Three Country

SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security No. 2017/4 December 2017 SECURITY AND ECONOMY ON SUMMARY w The Belt and Road Initiative THE BELT AND ROAD: THREE (BRI) is the result of a convergence of multiple COUNTRY CASE STUDIES Chinese domestic drivers and external developments. It holds significant potential to henrik hallgren and richard ghiasy* contribute to greater connectivity and stability in participating states, yet there is I. Introduction a need to include a wider spectrum of local and This SIPRI Insights examines how China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) international stakeholders in interacts with economic and security dynamics in three sample states from order to address concerns and three different regions across the Eurasian continent, each with a diverse mitigate backlashes. political, economic, and security background: Belarus, Myanmar and Uzbek- As shown in this SIPRI istan. In order to understand the BRI’s economic and, foremost, security Insights Paper, projects on the implications in these countries, it is imperative to first briefly examine what scale of those implemented within the BRI inevitably the initiative is in essence and what has compelled China to propose it. become part of existing local and cross-border security II. What is the Belt and Road Initiative? dynamics. They may also expose, and sometimes The BRI has evolved into an organizing principle of the foreign policy of exacerbate, local institutional President Xi Jinping’s administration.1 The BRI, which consists of the ter- weaknesses. Examples of these restrial Silk Road Economic Belt (hereafter the ‘Belt’) and the sea-based 21st issues are found in the three Century Maritime Silk Road (hereafter the ‘Road’), is an ambitious multi- countries studied here: Belarus, decade integration and cooperation vision. -

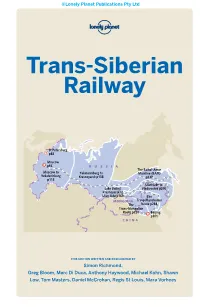

Trans-Siberian Railway 5

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Trans-Siberian Railway St Petersburg p88 Moscow p56 R U S S I A The Baikal-Amur Moscow to Yekaterinburg to Mainline (BAM) Yekaterinburg Krasnoyarsk p138 p237 p113 Ulan-Ude to Lake Baikal: Vladivostok p206 Krasnoyarsk to Ulan-Ude p168 The MONGOLIA Trans-Manchurian The Route p284 Trans-Mongolian Route p250 B›ij¸ng p301 C H I N A THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Simon Richmond, Greg Bloom, Marc Di Duca, Anthony Haywood, Michael Kohn, Shawn Low, Tom Masters, Daniel McCrohan, Regis St Louis, Mara Vorhees PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to the Trans- MOSCOW . 56 YEKATERINBURG TO Siberian Railway . 4 KRASNOYARSK . 138 Trans-Siberian Railway ST PETERSBURG . 88 Yekaterinburg . 142 Map . 6 Around Yekaterinburg . 149 The Trans-Siberian Tyumen . 150 Railway’s Top 16 . 8 MOSCOW TO YEKATERINBURG . .. 113 Tobolsk . 153 Need to Know . 16 Omsk . 156 Vladimir . 117 First Time . .18 Novosibirsk . 157 Suzdal . 120 Tomsk . 162 If You Like… . 20 Nizhny Novgorod . 127 Month by Month . 22 Perm . 132 LAKE BAIKAL: Around Perm . 136 Choosing Your Route . 24 KRASNOYARSK TO Kungur . 137 Itineraries . 30 ULAN-UDE . 168 Krasnoyarsk . 172 Booking Tickets . 33 Divnogorsk . 179 Arranging Your Visas . 41 Life on the Rails . 45 Journey at a Glance . 52 © IMAGES GETTY / FORMAN DAVID MARTIN MOOS / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / MOOS MARTIN IRKUTSK P179 Contents UNDERSTAND Irkutsk . 179 Blagoveshchensk . 218 History of the Listvyanka . 188 Birobidzhan . 220 Railway . 330 Port Baikal . 192 Khabarovsk . 221 Siberian & Far East Bolshie Koty . 193 Vladivostok . 227 Travellers . 345 Olkhon Island . 193 Russia Today . 350 South Baikal & the THE BAIKAL-AMUR Russian Culture & Tunka Valley . -

Trans-Siberian Route: Development of Trans-Continental Transportations

Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Second informal preparatory meeting for the 14th session of the Group of Experts on the Euro - Asian Transport Links 2-3 February 2016 Vienna, Hofburg Conference Centre Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations CCTT: working for the integration of the Trans-Siberian service 2 Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Forming mega blocks 3 Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Export flows between EATL countries, 2013 4 Source: Birgit Viohl, OSCE, compiled on the basis of Comtrade data for 2013. Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Dynamics of foreign trade volume change Trade volume growth 2011 2020 $739 billion 1,6 times $1 200 billion 2011 2020 USD bln China ЕС 567 800 Russia China 83,5 200 Turkey China 24 100 Trade volume growth between China and EC Russia Central Asia 42 60 from 117 mln. tonnes up to 170 mln. tonnes till 2020 Kazakhstan China 22,5 40 5 Source: forum1520.ru Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Sector of transport and logistics services: 3PL & 4PL 2PL 1PL4PL 3PL 6 Trans-Siberian route: development of trans-continental transportations Market structure of the transport and logistics services Effective business-model drivers Integrated Integrated logistics (4PL) logistics supply management Complex service made Contract logistics (complex 3PL) upon client’s demand Optimal routes choosing Warehouse -

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape │ 3 China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development strategy aims to build connectivity and co-operation across six main economic corridors encompassing China and: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasian countries; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; other countries of the Indian sub-continent; and Indochina. Asia needs USD 26 trillion in infrastructure investment to 2030 (Asian Development Bank, 2017), and China can certainly help to provide some of this. Its investments, by building infrastructure, have positive impacts on countries involved. Mutual benefit is a feature of the BRI which will also help to develop markets for China’s products in the long term and to alleviate industrial excess capacity in the short term. The BRI prioritises hardware (infrastructure) and funding first. This report explores and quantifies parts of the BRI strategy, the impact on other BRI-participating economies and some of the implications for OECD countries. It reproduces Chapter 2 from the 2018 edition of the OECD Business and Financial Outlook. 1. Introduction The world has a large infrastructure gap constraining trade, openness and future prosperity. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are working hard to help close this gap. Most recently China has commenced a major global effort to bolster this trend, a plan known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China and economies that have signed co-operation agreements with China on the BRI (henceforth BRI-participating economies1) have been rising as a share of the world economy. -

China's Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chapter 3

china’s eurasian century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative Nadège Rolland Chapter 3 Drivers of the Belt and Road Initiative This is a preview chapter from China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative. To purchase the monograph in which this chapter appears, visit <http://www.nbr.org> or contact <[email protected]>. © 2017 The National Bureau of Asian Research Chapter 3 Drivers of the Belt and Road Initiative In less than three years, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become the defining concept of China’s foreign policy and is now omnipresent in official rhetoric. It has established a general direction for the country’s efforts to build an interconnected, integrated Eurasian continent before 2050. Judging by the importance that the leadership has given the concept, and the quantity of financial, diplomatic, and intellectual resources that have been devoted to it, arguing that BRI is just an empty shell or vacuous political slogan has become increasingly difficult. Its paramount importance for the core leadership is also hard to deny. What is so crucial about the initiative that the vital energies of the entire country have been mobilized to give it the best chances of succeeding? Why is Beijing so eager to invest billions of dollars in Eurasia’s infrastructure connectivity? What are the drivers behind BRI and what are its goals? A first partial answer to these questions can be found in Xi Jinping’s speeches. In several instances, he has argued that -

Silk Road 2.0: US Strategy Toward China’S Belt and Road Initiative

Silk Road 2.0: US Strategy toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative Gal Luft Foreword by Joseph S. Nye, Jr. REVIVING THE SILK ROAD Announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the Silk Road in infrastructure projects including railways and power grids in central, Initiative, also known as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, aims to invest west, and southern Asia, as well as Africa and Europe. Silk Road 2.0 US Strategy toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative Atlantic Council Strategy Paper No. 11 © 2017 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-406-3 Cover art credit: Marco Polo’s caravan, from the Catalan Atlas, ca. 1375 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council, its partners, and funders do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s particular conclusions. October 2017 Atlantic Council Strategy Papers Editorial Board Executive Editors Mr. Frederick Kempe Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev Editor-in-Chief Mr. Barry Pavel Managing Editor Dr. Mathew Burrows Table of Contents -

Сhina's Impact on Russia's Economy Inozemtsev, V. August 2018 UI Brief

NO. 8 2018 PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS. WWW.UI.SE Сhina's impact on Russia’s economy Vladislav Inozemtsev On June 9, 2018, at the very same day when would have it, a Euro-Pacific country and is the G7 leaders got together at Manoir preordained to serve as a gigantic ‘bridge’ Richelieu in Québec, Canada, for their that links Asia to Europe. Therefore as more annual summit, Russia’s President doubts concerning Russia’s position in Vladimir Putin gleefully peacocked in in Europe were growing, the more active front of reporters in Qingdao, China, became talks on both Russian standing side by side with the leaders of ‘Eurasianism’ and its ‘pivot to the East’. China, India, and several post-Soviet states, The latter idea was elevated to a highest who all are now members of the Shanghai rank, just a tad shy from becoming a Cooperation Organization. His three-day- national ideology, with official Kremlin- long state visit to China was used to linked experts drafting endless reports demonstrate how close the ties between the called ‘Toward the Great Ocean’, two nations were nowadays and how elaborated and extended every year. Since important China is for Russia. mid-2000s, China became a total substitute to the ‘East’ in the Russian sociological Without any doubt, China now appears one discourse even geographically ‘Russia’s of the most crucial allies of the Russian East’ was still the West: if one travels Federation – especially in a world Mr. Putin straight East from Moscow, she/he would deems Russophobic, claiming that it ‘is get to Novosibirsk, Kamchatka, southern evident and in some countries is simply parts of Alaska, northern Quebec, Ireland, going beyond all bounds’.