Prehistory of Native Americans on the Central American Land Bridge: Colonization, Dispersal, and Divergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Glacial Flooding of the Bering Land Bridge Dated to 11 Cal Ka BP Based on New Geophysical and Sediment Records

Clim. Past, 13, 991–1005, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records Martin Jakobsson1, Christof Pearce1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Jan Backman1, Leif G. Anderson4, Natalia Barrientos1, Göran Björk4, Helen Coxall1, Agatha de Boer1, Larry A. Mayer5, Carl-Magnus Mörth1, Johan Nilsson6, Jayne E. Rattray1, Christian Stranne1,5, Igor Semiletov7,8, and Matt O’Regan1 1Department of Geological Sciences and Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 3US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia 20192, USA 4Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden 5Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 7Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 8Tomsk Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Martin Jakobsson ([email protected]) Received: 26 January 2017 – Discussion started: 13 February 2017 Accepted: 1 July 2017 – Published: 1 August 2017 Abstract. The Bering Strait connects the Arctic and Pacific Strait and the submergence of the large Bering Land Bridge. oceans and separates the North American and Asian land- Although the precise rates of sea level rise cannot be quanti- masses. The presently shallow ( ∼ 53 m) strait was exposed fied, our new results suggest that the late deglacial sea level during the sea level lowstand of the last glacial period, which rise was rapid and occurred after the end of the Younger permitted human migration across a land bridge today re- Dryas stadial. -

Your Cruise Secrets of Central America

Secrets of Central America From 1/4/2022 From Colón Ship: LE CHAMPLAIN to 1/14/2022 to Puerto Caldera PONANT takes you to discover Panama and Costa Rica with an 11-day expedition cruise. A circuit of great beauty around the isthmus of Panama, a link between two continents, which concentrates a biodiversity that is unique in the world, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean between dream islands, natural reserves and encounters with the fascinating local communities. Your journey in Central America will begin with an all-new port of call in the magnificent Portobelo Bay, between mangroves, tropical forest and discovery of the Congo culture. The fortifications of this former gateway to the New World are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You will then discover the golden sand and crystal-clear waters of the coral islets of the San Blas Islands. The Kuna live among the palm trees and pirogues; this people perpetuates, among other things, the traditional craft of molas, weaved textiles in sparkling colours. After sailing through the world-famous Panama Canal, your ship will stop in the Pearl Islands, which nestle in the Gulf of Panama. Your ship will then head for the magnificent Darien National Park in Panama. This little corner of paradise is a UNESCO World Heritage site and home to remarkable plants and wildlife. Sandy beaches, rocky coastlines, mangroves, swamps and tropical rainforests vie with each other for beauty and offer a feast for photographers. This will also be the occasion for meeting the astonishing semi-nomadic Emberas community. In Casa Orquideas, in the heart of a region that is home to Costa Rica’s most beautiful beaches, you will have the chance to visit a botanical garden with a sublime collection of tropical flowers. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

The Less-Splendid Isolation of the South American Continent

news and update ISSN 1948-6596 commentary The less-splendid isolation of the South American continent Only few biogeographic scenarios capture the im- lower Central America (Costa Rica) and South agination as much as the closure of the Isthmus of America (northern Colombia), and that some Panama. The establishment of this connection snapping shrimp populations were already split ended the “splendid isolation” of the South Amer- long before the Isthmus had finally closed (most ican continent (Simpson 1980), a continent that between 7–10 mya but some >15 mya). Next to had been unconnected to any other land mass for this, several papers showed that plants also mi- over 50 million years. When the Isthmus rose out grated between North and South America prior to of the water some 3 million years ago (mya) the the closure of the Isthmus (e.g., Erkens et al. 2007, Great American Biotic Interchange started. Since Bacon et al. 2013), although for plants it is difficult terrestrial biotic interchange was no longer to rule out that this happened via long-distance blocked by the Central American Seaway, dispersal. Thus, the new findings of Montes and (asymmetrical) invasion of taxa across this new colleagues fit much better with a wealth of evi- land bridge transformed biodiversity in North as dence from the biological realm that has been well as South America (Leigh et al. 2014). Or so amassed over the last years, than the old model of the story goes. a relatively rapid rise of the Isthmus. A recent paper by Montes et al. (2015) casts If the land-bridge was available much earli- further serious doubt on this scenario from a geo- er to many terrestrial organisms, the question that logical perspective. -

Day 2 Social Studies

Day 2 Social Studies - Read the article "The Earliest Americans" and complete the Build Your Map Skills page and Extinct Animals of North America page. Language Arts - Draw a self-portrait of yourself in the center of a piece of paper. Write a simile that describes parts of yourself. You must have at least 6 similes. For example, I would point to my hair and say "My hair is as red as a tomato." Reminder: a simile is a comparison of two things using like or as. Science- Help! My rose plant is no longer able to carry out photosynthesis, meaning that it can't make its own food anymore. Create an alternate system to keep my rose plant alive . Develop a new system and parts of the plant that will help it be able to obtain nutrients using pictures and descriptions. Math - Look through old magazines and newspapers for 15 numbers that have decimals. Cut out and paste the numbers onto paper in least to greatest order. Use the cut-out numbers to make up five word problems dealing with addition, subtraction, or multiplication. Make a separate key for the problems. Staple the problems and the key to the construction paper. he Earliest Americans. f \ \ Did you ever wonder in what kind of homes the first Americans lived or what kind of food they ate? Anthropologists and archaeologists devote their lives to answering such questions. Anthropologists are scientists who study all aspects of human beings, such as their society and culture. Archaeologists are scientists who use physical evidence and artifacts to analyze human cultures. -

Downloaded 09/25/21 09:51 PM UTC 800 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 131

MAY 2003 MAPES ET AL. 799 Diurnal Patterns of Rainfall in Northwestern South America. Part I: Observations and Context BRIAN E. MAPES NOAA±CIRES Climate Diagnostics Center, Boulder, Colorado THOMAS T. W ARNER AND MEI XU Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Colorado, and Research Applications Program, National Center for Atmospheric Research,* Boulder, Colorado ANDREW J. NEGRI NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Laboratory for Atmospheres, Greenbelt, Maryland (Manuscript received 10 January 2002, in ®nal form 29 August 2002) ABSTRACT One of the rainiest areas on earth, the Panama Bight and Paci®c (western) littoral of Colombia, is the focal point for a regional modeling study utilizing the ®fth-generation Pennsylvania State University±NCAR Mesoscale Model (MM5) with nested grids. In this ®rst of three parts, the observed climatology of the region is presented. The seasonal march of rainfall has a northwest±southeast axis, with western Colombia near the center, receiving rain throughout the year. This study focuses on the August±September season. The diurnal cycle of rainfall over land exhibits an afternoon maximum over most of South and Central America, typically composed of relatively small convective cloud systems. Over some large valleys in the Andes, and over Lake Maracaibo, a nocturnal maximum of rainfall is observed. A strong night/morning maximum of rainfall prevails over the coastal ocean, propagating offshore and westward with time. This offshore convection often takes the form of mesoscale convective systems with sizes comparable to the region's coastal concavities and other geographical features. The 10-day period of these model studies (28 August±7 September 1998) is shown to be a period of unusually active weather, but with a time-mean rainfall pattern similar to longer-term climatology. -

Synopsis Sheets CANAL DE PANAMA UK

Synopsis sheets Rivers of the World THE PANAMA CANAL Initiatives pour l’Avenir des Grands Fleuves The Panama Canal 80 km long, the Panama Canal links the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, forming a faster transoceanic route for merchant shipping than by passing via Cape Horn, at the southernmost tip of South America. A strategic hub for the world’s maritime trade, 15,000 ships pass through it every year. In 2016, a huge project of Canal’s enlargement was completed to double its capacity and accommodate the new generation ships, larger and longer, the Post Panamax. Now it has to face new challenges: competing projects are emerging and new shipping routes can be opened that would reduce the supremacy of the Panama Canal. A strategic route The origins Océan Atlantique The first attempt to build the canal dates back to 1880. France entrusted Ferdinand de Lesseps with the responsibility of its design and amassed considerable funds. However, the technical difficulties and above all a major financial scandal revealed in 1889 led to the bankruptcy of the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Inter-océanique du Panamá. The new Panama Canal Company took over but met the same fate, and in 1903 the treaty of Hay- Bunau-Varilla officialised the transfer of the operating and building rights to the canal to the United States. Built under the direction of G.W. Goethals, at the head of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the canal opened in 1914 and was finally handed over to Panama in 1999 by virtue of the Torrijos-Carter Treaty. -

100,000–11,000 Years Ago 75°

Copyrighted Material GREENLAND ICE SHEET 100,000–11,000 years ago 75° the spread of modern humans Berelekh 13,400–10,600 B ( E around the world during A ALASKA la R I ) SCANDINAVIAN n I e Bluefish Cave d N Arctic Circle G g 16,000 d ICE SHEET b G the ice age N i 25,000–10,000 r r i I d I b g e A R d Ice ) E n -fr SIBERIA a Dry Creek e l e B c All modern humans are descended from populations of ( o 35,000 Dyuktai Cvae 13,500 rri do 18,000 r Homo sapiens that lived in Africa c. 200,000 years ago. op LAURENTIDE en s ICE SHEET 1 Malaya Sya Around 60,000 years ago a small group of humans left 4 CORDILLERAN ,0 Cresswell 34,000 0 Africa and over the next 50,000 years its descendants 0 ICE SHEET – Crags 1 2 14,000 colonized all the world’s other continents except Antarctica, ,0 Wally’s Beach 0 Paviland Cave Mal’ta 0 EUROPE Mezhirich Mladecˇ in the process replacing all other human species. These 13,000–11,000 y 29,000 Denisova Cave 24,000 . 15,000 a 33,000 45,000 . Kostenki 41,000 migrations were aided by low sea levels during glaciations, Willendorf 40,000 Lascaux 41,700–39,500 which created land bridges linking islands and continents: Kennewick Cro Magnon 17,000 9,300 45° humans were able to reach most parts of the world on foot. Spirit 30,000 Cave Meadowcroft Altamira It was in this period of initial colonization of the globe that 10,600 Rockshelter 14,000 16,000 Lagar Velho Hintabayashi Tianyuan JAPAN modern racial characteristics evolved. -

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

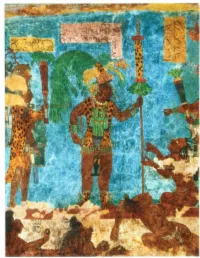

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

Beringia Vocabulary

Beringia Vocabulary 1) artifact--an object made by humans, such as a tool The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass th2a) t acrocnhnaecotloegdy A--sthiae astnudd yN oofr thhis Atomrice raicnad 1pr0e,h0i0s0to-r2ic5 ,000 years ago. Duringp tehoisp lteime, glaciers up to two miles thick covered large parts of North America, Europe and Asia. T3h)e ppaelerioondt owloagsy -c-athllee dst uthdey Pofl eeiasrtloyc leifen eb yIc loeo Akigneg. aSt ome very dry areas weforess iiclse-free during this time. Much of the Earth's water was locked up in the glaciers. Because of th4i)s psereah ilsetvoerilc d--rao pppeeridod s oigfn timficea bnetlfyo, ruep w troit t3e0n0 o fre et! Some areas that are now urencdoerrd weda theisr tboerycame dry land. The result was an intermittent land bridge stretching between 5) fossil--the remains, impression, imprint or bone of the two cao nlivtiinge nthtsin ugnder the present day Bering and Chukchi Seas. Scientists believe that Beringia was at its w6id) e esxtt ipnoctin--ta a sbpoeuctie 1s5 t,h0a0t 0h ayse adriesd a oguot., Anolt hloonuggehr icna lled a "bridge," the leaxnisdt ewnacse really a broad, grassy plain, which many animals stopped to feed on. 7) Pleistocene-- 2 million to 10,000 years ago Beringia The term Beringia refers to the 1,000-mile long landmass 1t0h,a0t0 c0o tnon 2e5c,t0e0d0 A yseiar asn adg No,o drtuhr inAgm teheri cpae r1io0d,0 k0n0o-w2n5 ,a0s0 0th e Pyleeaisrtso caegnoe. IDceu rAingge ,t hgilsa ctiiemrse ,u gpl atoc itewros mupile tso tthwicok mcoilveesr ethdi clakr ge pcaorvtse oref dN olartrhg eA mpaerrtisc ao, fE Nuorortphe ,A amned rAicsaia, Eaundro mpeu cahn odf Athseia e.a rth's wTahter pwearsio ldo cwkaeds ucpa lilne dth teh eg laPcleieirsst.o Tcheen es eIcae le Avegle d. -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities,