Muslim Identity & Tamil-Muslim Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Ampara District

IDP information updated as at 8 October, 2006 & DISTRICT : Ampara Access information updated as at 9 November, 2006 e Total Number of Displaced Persons: 2,135 BATTICALOA DEHIATTAKANDIYA MAHAOYA A 4 Northern IDP Sites Kalmunai Persons: 1,039 PADIYATHALAWA 7 Navithanveli 2 # A # # Persons: 82 # # # # # # # Sainthamarathu # UHANA Persons: 71 A 2 Karaitivu# 7 Karativu Sammanthurai# Ninthavur # Persons: 39 e Samanthuri A 4 Ninthanavur ! 1 Persons: 69 Ampara A3 Persons: 37 # Addachchenai Addalachchenai DY AMPARA Persons: 95 ERAGAMA Northern IDP Sites 5 Akkaraipattu A2 Akkaraipattu # Persons: 31 # Alayadiwembu # Kolavil Anamalai Alayadiwembu # Periyaneelavanai # Central Camp Persons: 508 # Navithanveli DAMANA # Pandiruppu Thirukkovil Senakudiyiruppu# # Thirukkovil # Kalmunai Savalakadai# # Persons: 53 Rufus Kulam! Pavata Kulam Natpatimunai# Kanchikudicharu ! ! ! Sri Valli Puram Kalmunai Kudi # A ! 4 Thangavelayutha Puram BADULLA ! Sainthamarathu# Thandiyadi 5 2 Karaitivu# A Pothuvil Ninthavur Persons: 111 Sammanthurai # # LAHUGALA A4 R.M. Nagar A # 4 A4 # Sinapputhu-# Victor Estate kudiyirupu Sina Ullai# Sarvodayapuram# # Pasarichenai ® Kilometers Divisional Ethnic No.of No.of Division Majority Families Individuals 02010 Addalachchenai Muslim 21 95 Akkaraipattu Muslim 6 31 MONERAGALA Alayadivembu Tamil 155 508 Kalmunai Muslim Muslim 10 32 Kalmunai Tamil Tamil 271 1,007 Karaitivu Tamil 10 39 Navithanveli Tamil 21 82 Ninthavur Muslim 10 37 Pothuvil Muslim,Tamil,Sinhala 33 111 Sainthamarathu Muslim 12 71 Indian Ocean Samanthurai Muslim 22 69 Thirukkovil Tamil 16 53 Total 587 2,135 Area Detail Legend Data sources: MapNumber: OCHA/LK/Ampara/IDP/02/V6 Produced through the generous support of: IDP numbers as of 8 November 2006: Access details This map is designed for printing on A4 Government Agenct's Office, UNHCR Amapra. -

PDF995, Job 2

MONITORING FACTORS AFFECTING THE SRI LANKAN PEACE PROCESS CLUSTER REPORT FIRST QUARTERLY FEBRUARY 2006 œ APRIL 2006 CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS CLUSTER Page Number PEACE TALKS AND NEGOTIATIONS CLUSTER.................................................... 2 POLITICAL ENVIRONM ENT CLUSTER.....................................................................13 SECURITY CLUSTER.............................................................................................................23 LEGAL & CONSTIIUTIONAL CLUSTER......................................................................46 ECONOM ICS CLUSTER.........................................................................................................51 RELIEF, REHABILITATION & RECONSTRUCTION CLUSTER......................61 PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS & SOCIAL ATTITUDES CLUSTER................................70 M EDIA CLUSTER.......................................................................................................................76. ENDNOTES.....… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..84 M ETHODOLOGY The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) has conducted the project “Monitoring the Factors Affecting the Peace Process” since 2005. The output of this project is a series of Quarterly Reports. This is the fifth of such reports. It should be noted that this Quarterly Report covers the months of February, March and April. Having identified a number of key factors that impact the peace process, they have been monitored observing change or stasis through -

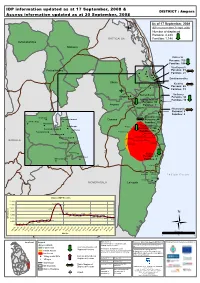

SL AMP IDP ACCESS V37 30 09 2008 with UNHCR GA Data

IDP information updated as at 17 September, 2008 & DISTRICT : Ampara Access information updated as at 30 September, 2008 As of 17 September, 2008 e (IDP movement after 7th April, 2006) Number of displaced Persons: 4,223 BATTICALOA Families: 1,148 Dehiattakandiya Mahaoya A 4 Kalmunai Persons: 759 Families: 185 Navithanveli Padiyathalawa 7 Persons: 81 2 ! ! A ! Families: 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sainthamarathu ! Uhana Karativu A ! 2 Karaitivu 7 Persons: 49 Sammanthurai ! Ninthavur ! Families: 13 e A 4 Ninthavur ! 1 Samanthurai Ampara A3 Persons: 32 Addalachchenai ! Families: 10 Addachchenai Persons: 39 Ampara Families: 7 Eragama 5 Akkaraipattu A2 ! Akkaraipattu Persons: 9 ! Alayadiwembu ! Kolavil Families: 2 Alayadiwembu Anamalai ! Periyaneelavanai Damana Persons: 445 ! Central Camp Families: 132 ! Navithanveli ! Thirukkovil Thirukkovil Pandiruppu Thottama Senakudiyiruppu ! ! ! Persons: 2,786 ! Kalmunai Savalakadai ! ! Pannalgama ! Families: 774 Rufus Kulam ! ! Natpatimunai Sri Valli Puram ! ! ! ! Kanchikudicharu Pavata Kulam Kalmunai Kudi Kovilmadu A ! ! 4 Thangavelayutha Puram BADULLA ! Sainthamarathu ! Thandiyadi Bakmitiyawa ! 5 2 Karaitivu ! A Pothuvil Ninthavur Persons: 23 Sammanthurai ! Families: 4 ! A4 R.M. Nagar A ! 4 A4 ! Sinapputhu- ! Victor Estate kudiyirupu Indian Ocean Sina Ullai ! Sarvodayapuram ! ! MONERAGALA Lahugala Pasarichenai District IDP Trends 14,000 12,143 12,000 11,702 10,000 8,752 8,000 6,290 5,775 6,329 5,695 5,569 6,000 5,115 5,106 5,775 5,637 5,564 4,278 5,188 5,106 IDP Numbers IDP 4,000 4,431 2,384 4,223 2,217 2,471 -

Economic and Cultural History of Tamilnadu from Sangam Age to 1800 C.E

I - M.A. HISTORY Code No. 18KP1HO3 SOCIO – ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAMILNADU FROM SANGAM AGE TO 1800 C.E. UNIT – I Sources The Literay Sources Sangam Period The consisted, of Tolkappiyam a Tamil grammar work, eight Anthologies (Ettutogai), the ten poems (Padinen kell kanakku ) the twin epics, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai and other poems. The sangam works dealt with the aharm and puram life of the people. To collect various information regarding politics, society, religion and economy of the sangam period, these works are useful. The sangam works were secular in character. Kallabhra period The religious works such as Tamil Navalar Charital,Periyapuranam and Yapperumkalam were religious oriented, they served little purpose. Pallava Period Devaram, written by Apper, simdarar and Sambandar gave references tot eh socio economic and the religious activities of the Pallava age. The religious oriented Nalayira Tivya Prabandam also provided materials to know the relation of the Pallavas with the contemporary rulers of South India. The Nandikkalambakam of Nandivarman III and Bharatavenba of Perumdevanar give a clear account of the political activities of Nandivarman III. The early pandya period Limited Tamil sources are available for the study of the early Pandyas. The Pandikkovai, the Periyapuranam, the Divya Suri Carita and the Guruparamparai throw light on the study of the Pandyas. The Chola Period The chola empire under Vijayalaya and his successors witnessed one of the progressive periods of literary and religious revival in south India The works of South Indian Vishnavism arranged by Nambi Andar Nambi provide amble information about the domination of Hindu religion in south India. -

PART SEVEN the Eastern Province

Preliminary Survey of Tsunami-affected Monuments and Sites in the Maritime Region of Sri Lanka PART SEVEN The Eastern Province Prof. S. Maunaguru and The Faculty of Arts and Culture Eastern University of Sri Lanka March 2005 INTRODUCTION The Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Ampara Districts, affected by the tsunami of 26 December 2004 lie on the East Coast. If the three affected districts on the East Coast are taken together, they account for more then 50 percent of the total displacement that occurred along the Sri Lankan coastline as a result of the tsunami. According to official figures up to January 2005, the largest number IDPs are from the Batticaloa and Ampara Districts. The Eastern University of Sri Lanka, which is located in Vantharumoolai, Batticaloa, was indirectly affected mostly because the students and staff of the Faculty of Arts and Culture were badly affected by the disaster. One third of the students were severely affected and some of them still live in camps for displaced persons. Of the members of the academic staff, 12 were severely affected and some are still living away from their homes. It took awhile for the staff to be able to get involved in academic work again. Due to this very difficult situation, the survey of damaged cultural property was not possible till March according to the request made by ICOMOS, Sri Lanka. This is also due to difficulties with transport as many roads and bridges are still in a dilapidated condition and the roads towards the coast in some places are still blocked by piles of garbage created by the tsunami. -

Pdf | 181.7 Kb

Inter-Agency Standing Committee Country Team IASC Colombo Sri Lanka SITUATION REPORT # 97 KILINOCHCHI, MULLAITIVU, MANNAR, VAVUNIYA, TRINCOMALEE, BATTICALOA, and AMPARA DISTRICTS 18-25 October 2007 24 October, the United Nations commemorated the 62nd United Nations Day at the UN Compound in Colombo 7. The commemoration began with a United Nations flag hoisting ceremony, accompanied by the hymn to the UN and was followed by a speech of the United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Neil Buhne. The guests were the Additional Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Maduwegedera, heads of United Nations agencies, partners, students, the media and UN colleagues. The full text of the RC/HC’s speech is attached. KILINOCHCHI & MULLAITIVU DISTRICTS Situation Update • For the third time in 2 weeks, new procedures for crossing the Omanthai Forward Defence Line (FDL) have been given to the humanitarian community. The request requires organizations to submit the name of the authorizing officer apart from a full staff list of the organization. • Shelling continues in areas south of Kilinochchi district, Vadamarachchi East and coastal parts of Poonakary and therefore these areas remain inaccessible to humanitarian agencies. Internally Displaced Persons • District Secretariat of Kilinochchi reported as at 22 October that the IDP figure for Kilinochchi district is 13,219 IDP families (50,994 individuals) while Mullaitivu District Secretariat reported 9,068 IDP families (32,370 individuals) as of the same date. Sector Response Shelter • Sewa Lanka Foundation as an implementing partner for IOM in temporary shelter [TS] construction in Manthai west- Mannar areas reported on 24 October that they started the construction works for 150 TS in Illupakadawai village in Manthai west division last week. -

Eastern Province

Resettlement Due Diligence Report June 2017 SRI: Second Integrated Road Investment Program Eastern Province Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Higher Education and Highways for the Government of Sri Lanka and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2017) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee (SLRl} SLR1.00 = $ 0.00655 $1.00 = Rs 152.63 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DS - Divisional Secretariat EP - Eastern Province EPL - Environmental Protection License DDR - Due Diligence Report FGD - Focus Group Discussion GDP - Gross Domestic Production GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau HH - Household iRoad - Integrated Road Investment Program iRoad 2 - Second Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement MoHEH - Ministry of Higher Education and Highways NWS&DB - National Water Supply and Drainage Board OFC - Other Field Crops PS - Pradeshiya Sabha PPE - Personal Protective Equipment’s RDA - Road Development Authority RF - Resettlement Framework ROW - Right of Way SAPE - Survey and Preliminary Engineering SLR - Sri Lankan Rupees This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Sociology Contributions to Indian

Contributions to Indian Sociology http://cis.sagepub.com Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective Dennis B. McGilvray Contributions to Indian Sociology 1998; 32; 433 DOI: 10.1177/006996679803200213 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/32/2/433 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Contributions to Indian Sociology can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cis.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 34 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/32/2/433 Downloaded from http://cis.sagepub.com at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on August 31, 2008 © 1998 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective Dennis B. McGilvray In the context of Sri Lanka’s inter-ethnic conflict between the Tamils and the Sinhalese, the Tamil- speaking Muslims or Moors occupy a unique position. Unlike the historically insurrectionist Māppilas of Kerala or the assimilationist Marakkāyars of coastal Tamilnadu, the Sri Lankan Muslim urban elite has fostered an Arab Islamic identity in the 20th century which has severed them from the Dravidian separatist campaign of the Hindu and Christian Tamils. This has placed the Muslim farmers in the Tamil-speaking north-eastern region in an awkward and dangeruus situation, because they would be geographically central to any future Tamil homeland. -

Print Culture Amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, C.1860-1960

Working Paper No. 167 Print Culture amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c.1860-1960 by Dr. S.M.A.K. Fakhri Madras Institute of Development Studies 79, Second Main Road, Gandhi Nagar Adyar, Chennai 600 020 February 2002 Print Culture amongst Tamils and Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c. 1860-1960 Authors name and institutional affiliation: Dr SM AK Fakhri Affiliate, June-December 2001 Madras Institute of Development Studies. Abstract of paper: This paper is about the significance of print in the history of Tamil migration to Southeast Asia. During the age of Empire people migrated from India to colonial Malaya resulting in the creation of newer cultural and social groups in their destination (s). What this .meant in a post-colonial context is that while they are citizens of a country they share languages of culture, religion and politics with 'ethnic kin' in other countries. Tamils and Tamil-speaking Muslims from India were one such highly mobile group. They could truly be called 'Bay of Bengal transnational communities' dispersed in Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam. The construction of post-colonial national boundaries constricted but did not affect the transnationalism of Tamils across geographies and nation-states. A thriving and successful print culture is a pointer to the manner in which Tamils and Tamil Muslim expressed their transnational (Tamil) identities. Such a print culture this paper suggests is a rich and valuable source of social history. Keywords Print, Print Culture, transnational communities, migration, mobility, social history, Tamils, Tamil Muslims, India, Indian migrants, Indian Ocean region. Acknowledgements This paper was presented at the Conference on 'Southeast Asian Historiography since 1945' July 30 to August I, 1999 by the History Section, School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia as 'Cues for Historiography?•: Print Culture, Print Leaders and Print Mobility among Tamil Muslims in Southeast Asia, c. -

Comparative Research Into Conflict in Tamil Nadu 7

Comparative Research Into Conflict In Tamil Nadu 7 Chapter 1 Comparative Research into Conflict in Tamil Nadu Introduction In India 2020. A vision for the new millennium Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, eleventh president of India (2002–2007) and hailing from Tamil Nadu, recalls the lasting impression left on him by Mahatma Gandhi’s resolve to be with those affected by religio-political conflict on the historic day of Indian independence: “I was in my teens when India became independent. The headmaster of my school used to take us to hear the news on the only available radio. We used to hear of the events in Delhi, and many speeches and commentaries. I used to distribute the morning newspaper Dinamani to households in Rameswaram, to help my brother with his work. While going on my daily morning round I also read the news items. One report which particularly struck me appeared in the heady days following independence. It was a time of celebration and the country’s leaders were gathered in Delhi, addressing themselves to the momentous tasks that faced the government. At this moment, however, far from being at the centre of power, the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi, was away in No- akhali caring for the riot victims and trying to heal the wounds inflicted by communal rioting. How many persons would have such courage of conviction as did Gandhiji at a time when the nation was at his command?” (Abdul Kalam & Rajan 1998, 3–4). This narrative in a way captures the overall rationale and context of our re- search: it shows how religions can motivate people to get caught up in the trag- edy of violence or become an embodiment of compassion amidst violence and death. -

Rapid Livelihoods Assessment in Coastal Ampara & Batticaloa Districts, Sri Lanka

RAPID LIVELIHOODS ASSESSMENT IN COASTAL AMPARA & BATTICALOA DISTRICTS, SRI LANKA 18th January, 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Save the Children carried out a rapid livelihoods assessment in coastal areas of Ampara and Batticaloa districts between January 5th and 11th to acquire a basic understanding of the different economic activities undertaken prior to the December 26th tsunami within affected communities and nearby towns and villages. The information will be used primarily to inform SC’s own interventions, but may also be of interest to other agencies working in this sector. Information was gathered using qualitative semi-structured interviews with individuals and small groups of purposively-sampled livelihood groups. It is acknowledged that information is incomplete, but it is hoped that the qualitative and contextual information here will assist in interpreting more quantitative data gathered by other agencies. For the population affected by damage to their homes, repair and reconstruction of housing was consistently listed as the top priority in the recovery process, and in many cases is a necessary first step before they can focus their energies of income-earning activities. The assessment confirmed that the largest affected group in these areas were fishermen, but highlights that there are at least 4 categories of fishermen, with different arrangements for payment and sharing of fishing catches, and with very different pre-tsunami incomes. For this group, repair or replacement of fishing boats and equipment is a clear priority. Unskilled casual labourers form a substantial part of the population, and are at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. They were employed in a variety of activities, some of which are seasonal, such as house/ garden cleaning, assisting masons and carpenters, assisting fishermen, and harvesting nearby rice fields.