Rapid Livelihoods Assessment in Coastal Ampara & Batticaloa Districts, Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pta and Hand Tools

Precision, Quality, Innovation PTA AND HAND TOOLS Hole Saws Hacksaws Jig Saws Reciprocating Saws Portable Band Saws Measuring Tapes Utility Knives Levels Plumb Bobs Chalk Rules & Squares Calipers Protractors Punches Shop Tools Lubricant Catalog 71 PRECISION, QUALITY, iNNOVATiON For more than 135 years, manufacturers, builders and craftsmen worldwide have depended upon precision tools and saws from The L.S. Starrett Company to ensure the consistent quality of their work. They know that the Starrett name on a saw blade, hand tool or measuring tool ensures exceptional quality, innovative products and expert technical assistance. With strict quality control, state-of-the-art equipment and an ongoing commitment to producing superior tools, the thousands of products in today's Starrett line continue to be the most accurate, robust and durable tools available. This catalog features those tools most widely used on a jobsite or in a workshop environment. 2 hole saws Our new line includes the Fast Cut and Deep Cut bi-metal saws, and application-specific hole saws engineered specifically for certain materials, power tools and jobs. A full line of accessories, including Quick-Hitch™ arbors, pilot drills and protective cowls, enables you to optimise each job with safe, cost efficient solutions. 09 hacksaws Hacksaw Safe-Flex® and Grey-Flex® blades and frames, Redstripe® power hack blades, compass and PVC saws to assist you with all of your hand sawing needs. 31 jig saws Our Unified Shank® jig saws are developed for wood, metal and multi-purpose cutting. The Starrett bi-metal unique® saw technology provides our saws with 170% greater resistance to breakage, cut faster and last longer than other saws. -

24 July 2019 1 Logistics Information INEB Conference 2019 Deer Park

Update: 24 July 2019 Logistics Information INEB Conference 2019 Deer Park Institute, Bir, India Event date and venue: 21 October – Visit Main Temple, McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala 22-24 October – INEB Conference, Deer Park Institute, Bir 25 October – AC/EC meeting – Deer Park Institute, Bir 21 October 2019 Main Temple, McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala Location: https://goo.gl/maps/683MKzAZePgBtUB37 Travel - How to get to McLeod Ganj from New Delhi By plane From New Delhi, book a ticket through either the Air India/Alliance Air (www.airindia.in) or Spicejet (www.spicejet.com) that flies to Kangra airport (DHM), which is about 20 km from McLeod Ganj. Then take a taxi from the Kangra airport to McLeod Ganj which costs approximately Rs900 one way and it takes around 45 minutes. By bus There are several bus companies running from New Delhi to McLeod Ganj. It’s recommended to use the government bus called, HRTC (Himachal Road Transport Corporation). You can book a ticket online directly via its website https://hrtchp.com (Indian phone number required) or a reliable agent’s website www.redbus.in at similar costs - around Rs850 (non-AC bus) to Rs1,390 (AC volvo bus). The trip on a HRTC bus takes about 12 hours from ISBT (Inter State Bus Terminal) at Kashmere Gate in New Delhi to McLeod Ganj bus station (2 min walk to the main square). Most buses travel at night with two stops for food and toilets. By train There is no train station in Dharamsala or McLeod Ganj. You can take train from New Delhi to the Pathankot Cantonment railway station (Pathankot Cantt), then take a taxi to McLeod Ganj (Rs3,000, 2.5 hours). -

Accessories 1

MOTOMAN Accessories 1 Accessories Program www.yaskawa.eu.com Masters of Robotics, Motion and Control Contents Accessories Cable Retraction System for Teach Pendants ..................................................... 5 Media Packages suitable for all Applications ....................................................... 7 Robot Pedestals and Robot Base Plates for MOTOMAN Robots ............................................................ 9 External Drive Axes Packages for MOTOMAN Robots with DX200 Controller ....................... 17 Touch Sensor Search Sensor with Welding Wire .......................................... 21 MotoFit Force Control Assembly Tool ................................................ 23 YASKAWA Vision System Camera & Software MotoSight2D .......................................... 25 Fieldbus Systems .................................................................. 27 4 Accessories MOTOMAN Accessories 5 Cable Retraction System for Teach Pendants The automatic YASKAWA cable retraction system has been specially developed for the connecting cables of industrial robot teach pendants. This system is used to improve work safety in the production area and is a recognized accident prevention measure. The stable housing is made of impactresistant plastic, while the mounting bracket is made of steel plate, enabling alignment of the retraction system housing in the direction in which the cable is pulled out. The cable deflection pulley is fitted with a spring element for cable retraction. Additionally, a releas- able cable -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

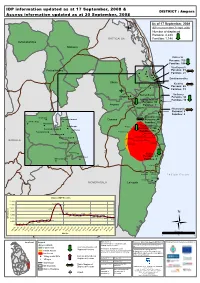

Ampara District

IDP information updated as at 8 October, 2006 & DISTRICT : Ampara Access information updated as at 9 November, 2006 e Total Number of Displaced Persons: 2,135 BATTICALOA DEHIATTAKANDIYA MAHAOYA A 4 Northern IDP Sites Kalmunai Persons: 1,039 PADIYATHALAWA 7 Navithanveli 2 # A # # Persons: 82 # # # # # # # Sainthamarathu # UHANA Persons: 71 A 2 Karaitivu# 7 Karativu Sammanthurai# Ninthavur # Persons: 39 e Samanthuri A 4 Ninthanavur ! 1 Persons: 69 Ampara A3 Persons: 37 # Addachchenai Addalachchenai DY AMPARA Persons: 95 ERAGAMA Northern IDP Sites 5 Akkaraipattu A2 Akkaraipattu # Persons: 31 # Alayadiwembu # Kolavil Anamalai Alayadiwembu # Periyaneelavanai # Central Camp Persons: 508 # Navithanveli DAMANA # Pandiruppu Thirukkovil Senakudiyiruppu# # Thirukkovil # Kalmunai Savalakadai# # Persons: 53 Rufus Kulam! Pavata Kulam Natpatimunai# Kanchikudicharu ! ! ! Sri Valli Puram Kalmunai Kudi # A ! 4 Thangavelayutha Puram BADULLA ! Sainthamarathu# Thandiyadi 5 2 Karaitivu# A Pothuvil Ninthavur Persons: 111 Sammanthurai # # LAHUGALA A4 R.M. Nagar A # 4 A4 # Sinapputhu-# Victor Estate kudiyirupu Sina Ullai# Sarvodayapuram# # Pasarichenai ® Kilometers Divisional Ethnic No.of No.of Division Majority Families Individuals 02010 Addalachchenai Muslim 21 95 Akkaraipattu Muslim 6 31 MONERAGALA Alayadivembu Tamil 155 508 Kalmunai Muslim Muslim 10 32 Kalmunai Tamil Tamil 271 1,007 Karaitivu Tamil 10 39 Navithanveli Tamil 21 82 Ninthavur Muslim 10 37 Pothuvil Muslim,Tamil,Sinhala 33 111 Sainthamarathu Muslim 12 71 Indian Ocean Samanthurai Muslim 22 69 Thirukkovil Tamil 16 53 Total 587 2,135 Area Detail Legend Data sources: MapNumber: OCHA/LK/Ampara/IDP/02/V6 Produced through the generous support of: IDP numbers as of 8 November 2006: Access details This map is designed for printing on A4 Government Agenct's Office, UNHCR Amapra. -

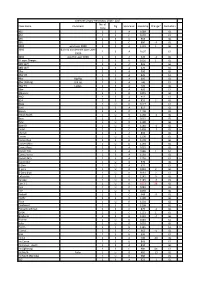

Great Lakes Handicaps 2018-19 05/12/18

Great Lakes Handicaps 2018-19 05/12/18 Type Boat Class Handicap RYA / Class 2018/19 Difference to Change from Notes: See key below Status Handicap Handicap RYA / Class 2017/18 D 405 RYA - A 1089 1089 D 420 RYA 1111 1086 -25 16 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 470 Class 973 973 10 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 505 RYA 903 878 -25 -2 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 2000 RYA 1109 1109 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 3000 Class 1007 1007 D 4000 RYA 917 917 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 12 sqm Sharpie RYA - A 1026 1026 D 12ft Skiff Class 879 857 -22 22 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 18ft Skiff Class 675 670 -5 Note 4: Based on boat specs K 2.4m RYA - A 1240 1230 -10 10 Note 3: Based on club data D 29er RYA 912 905 -7 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 29er XX Class 830 820 -10 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 49er RYA 697 697 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 49er (Old rig) Class 740 740 D 49er FX Class ?? 720 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 59er Class 905 905 M A Class Classic RYA 684 684 M A Class Foiling SCHRS n/a 656 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Albacore RYA 1038 1055 17 Note 2: Based on SWS data D AltO RYA 920 920 3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D B14 RYA - E 862 857 -5 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D Blaze RYA 1027 1027 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Boss Class 847 832 -15 15 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Bosun RYA - A 1198 1198 D British Moth RYA 1155 1155 D Buzz RYA - E 1026 1026 3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Byte Class 1190 1190 D Byte CI Class ?? 1177 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Byte CII RYA 1144 1144 -3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Cadet RYA -

SL AMP IDP ACCESS V37 30 09 2008 with UNHCR GA Data

IDP information updated as at 17 September, 2008 & DISTRICT : Ampara Access information updated as at 30 September, 2008 As of 17 September, 2008 e (IDP movement after 7th April, 2006) Number of displaced Persons: 4,223 BATTICALOA Families: 1,148 Dehiattakandiya Mahaoya A 4 Kalmunai Persons: 759 Families: 185 Navithanveli Padiyathalawa 7 Persons: 81 2 ! ! A ! Families: 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sainthamarathu ! Uhana Karativu A ! 2 Karaitivu 7 Persons: 49 Sammanthurai ! Ninthavur ! Families: 13 e A 4 Ninthavur ! 1 Samanthurai Ampara A3 Persons: 32 Addalachchenai ! Families: 10 Addachchenai Persons: 39 Ampara Families: 7 Eragama 5 Akkaraipattu A2 ! Akkaraipattu Persons: 9 ! Alayadiwembu ! Kolavil Families: 2 Alayadiwembu Anamalai ! Periyaneelavanai Damana Persons: 445 ! Central Camp Families: 132 ! Navithanveli ! Thirukkovil Thirukkovil Pandiruppu Thottama Senakudiyiruppu ! ! ! Persons: 2,786 ! Kalmunai Savalakadai ! ! Pannalgama ! Families: 774 Rufus Kulam ! ! Natpatimunai Sri Valli Puram ! ! ! ! Kanchikudicharu Pavata Kulam Kalmunai Kudi Kovilmadu A ! ! 4 Thangavelayutha Puram BADULLA ! Sainthamarathu ! Thandiyadi Bakmitiyawa ! 5 2 Karaitivu ! A Pothuvil Ninthavur Persons: 23 Sammanthurai ! Families: 4 ! A4 R.M. Nagar A ! 4 A4 ! Sinapputhu- ! Victor Estate kudiyirupu Indian Ocean Sina Ullai ! Sarvodayapuram ! ! MONERAGALA Lahugala Pasarichenai District IDP Trends 14,000 12,143 12,000 11,702 10,000 8,752 8,000 6,290 5,775 6,329 5,695 5,569 6,000 5,115 5,106 5,775 5,637 5,564 4,278 5,188 5,106 IDP Numbers IDP 4,000 4,431 2,384 4,223 2,217 2,471 -

Great Lakes Handicaps 2020-21.Xls

Great Lakes Handicaps 2020-21 01/10/2020 Type Boat Class Handicap RYA / Class Great Lakes Difference to Change from Notes for handicap changes: Status Handicap Handicap RYA / Class 2019/20 See key below D 405 RYA - A 1089 1089 D 420 RYA 1105 1083 -22 -3 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 470 RYA - A 973 973 D 505 RYA 903 883 -20 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 2000 RYA 1114 1090 -24 -10 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 3000 Class 1007 1007 D 4000 RYA - A 917 917 D 12 sqm Sharpie RYA - A 1026 1026 D 12ft Skiff Class 879 868 -11 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 18ft Skiff Class 675 675 K 2.4m RYA - A 1240 1230 -10 Note 3: Based on club data D 29er RYA 903 903 -4 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 29er XX Class 830 830 D 49er RYA - A 697 697 D 49er (Old rig) Class 740 740 D 49er FX Class ?? 720 D 59er Class 905 905 M A Class Classic RYA 684 684 M A Class Foiling SCHRS n/a 641 -15 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Albacore RYA 1040 1053 13 -2 Note 2: Based on SWS data D AltO RYA - A 926 926 D B14 RYA - E 860 860 D Blaze RYA 1033 1033 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Boss RYA - A 847 847 D Bosun RYA - A 1198 1198 D British Moth RYA 1160 1155 -5 D Buzz RYA - A 1030 1030 D Byte RYA - A 1190 1190 D Byte CI RYA - E 1215 1215 38 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Byte CII RYA 1135 1135 -3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Cadet RYA - E 1430 1435 5 M Catapult RYA 898 898 -5 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class M Challenger RYA 1173 1162 -11 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub RYA - A 903 890 -13 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub 97 Class ?? 970 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub -

PART SEVEN the Eastern Province

Preliminary Survey of Tsunami-affected Monuments and Sites in the Maritime Region of Sri Lanka PART SEVEN The Eastern Province Prof. S. Maunaguru and The Faculty of Arts and Culture Eastern University of Sri Lanka March 2005 INTRODUCTION The Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Ampara Districts, affected by the tsunami of 26 December 2004 lie on the East Coast. If the three affected districts on the East Coast are taken together, they account for more then 50 percent of the total displacement that occurred along the Sri Lankan coastline as a result of the tsunami. According to official figures up to January 2005, the largest number IDPs are from the Batticaloa and Ampara Districts. The Eastern University of Sri Lanka, which is located in Vantharumoolai, Batticaloa, was indirectly affected mostly because the students and staff of the Faculty of Arts and Culture were badly affected by the disaster. One third of the students were severely affected and some of them still live in camps for displaced persons. Of the members of the academic staff, 12 were severely affected and some are still living away from their homes. It took awhile for the staff to be able to get involved in academic work again. Due to this very difficult situation, the survey of damaged cultural property was not possible till March according to the request made by ICOMOS, Sri Lanka. This is also due to difficulties with transport as many roads and bridges are still in a dilapidated condition and the roads towards the coast in some places are still blocked by piles of garbage created by the tsunami. -

Robot Pedestals and Robot Base Plates for MOTOMAN Robots

Robot pedestals and Robot base plates for MOTOMAN robots As a robot manufacturer with our own systems engineering facilities, we are able to offer not just the robot, but also matching pedestals or base plates from a single source. This not only saves you organizational effort, but also ensures that you receive coordinated products that can be used directly. KEY BENEFITS • Suitable for our most common robot models • Wide range to meet your requirements • High-quality painted steel structure • Simple fastening by means of anchor bolts/bolted connections • Height-adjustable • Re-usable with the same robot model YASKAWA Europe GmbH Robotics Yaskawastraße 1 85391 Allershausen, Germany Tel. +49 (0) 8166 90-0 www.yaskawa.eu.com [email protected] www.yaskawa.eu.com Robot pedestals XS-series B C • Robot pedestals for MOTOMAN robots • Steel structure, painted, RAL 5005 (blue) • Fastening by means of anchor bolts/bolted connections • Height-adjustable For the following robot types: A MH5S II, MH5LS II, MH5F, MH5LF, GP7, GP8 E G L F D XS-series Robot pedestals A B C D E F G L Weight SAP XS-RS200 200 240 240 400 400 320 320 4 x Ø 27 37 172543 XS-RS300 308 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 39 149625 XS-RS400 408 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 44 167318 XS-RS500 500 240 240 400 400 320 320 4 x Ø 27 50 172536 XS-RS600 608 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 58 146090 XS-RS900 908 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 72 153560 Robot pedestals S-series B C • Robot pedestals for MOTOMAN robots • Steel structure, painted, RAL 5005 (blue) • Fastening by -

Pdf | 181.7 Kb

Inter-Agency Standing Committee Country Team IASC Colombo Sri Lanka SITUATION REPORT # 97 KILINOCHCHI, MULLAITIVU, MANNAR, VAVUNIYA, TRINCOMALEE, BATTICALOA, and AMPARA DISTRICTS 18-25 October 2007 24 October, the United Nations commemorated the 62nd United Nations Day at the UN Compound in Colombo 7. The commemoration began with a United Nations flag hoisting ceremony, accompanied by the hymn to the UN and was followed by a speech of the United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Neil Buhne. The guests were the Additional Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Maduwegedera, heads of United Nations agencies, partners, students, the media and UN colleagues. The full text of the RC/HC’s speech is attached. KILINOCHCHI & MULLAITIVU DISTRICTS Situation Update • For the third time in 2 weeks, new procedures for crossing the Omanthai Forward Defence Line (FDL) have been given to the humanitarian community. The request requires organizations to submit the name of the authorizing officer apart from a full staff list of the organization. • Shelling continues in areas south of Kilinochchi district, Vadamarachchi East and coastal parts of Poonakary and therefore these areas remain inaccessible to humanitarian agencies. Internally Displaced Persons • District Secretariat of Kilinochchi reported as at 22 October that the IDP figure for Kilinochchi district is 13,219 IDP families (50,994 individuals) while Mullaitivu District Secretariat reported 9,068 IDP families (32,370 individuals) as of the same date. Sector Response Shelter • Sewa Lanka Foundation as an implementing partner for IOM in temporary shelter [TS] construction in Manthai west- Mannar areas reported on 24 October that they started the construction works for 150 TS in Illupakadawai village in Manthai west division last week. -

Class Name Comment No. of Crew Rig Spinnaker Handicap Change

Grafham Dinghy Handicaps, 2016 - 2017 No. of Class Name Comment Rig Spinnaker Handicap Change* Derivation Crew 405 2 S A 1089 GL 420 2 S C 1070 GL 470 2 S C 963 GL 505 2 S C 880 -3 GL 2000 was Laser 2000 2 S A 1101 1 GL 3000 Built by Vandercraft (was Laser 2 S A 1007 GL 3000) 4000 was the Laser 4000 2 S A 920 -2 GL 12 sqm Sharpie 2 S 0 1026 1 GL 12ft Skiff 3 S A 835 GL 18ft Skiff 2 S A 670 GL x 29er 2 S A 900 GL 29er XX 2 S A 820 GL 49er Big Rig 2 S A 695 GL 49er (Old rig) Old rig 2 S A 740 GL 49er FX Ladies 2 S A 720 GL 59er 2 S A 905 GL Albacore 2 S 0 1055 GL AltO 2 S A 912 GL B14 2 S A 852 2 GL Blaze 1 U 0 1027 GL Boss 2 S A 817 GL Bosun 2 S 0 1198 GL British Moth 1 U 0 1158 -2 GL Buzz 2 S A 1015 GL Byte 1 U 0 1190 GL Byte CII 1 U 0 1148 -2 GL Cadet 2 S C 1428 -7 GL x Cherub 2 S A 890 GL Comet 1 U 0 1200 GL Comet Duo 2 S 0 1178 GL Comet Mino 1 U 0 1193 GL Comet Race 2 S A 1025 GL Comet Trio 2 S A 1086 1 GL Comet Versa 2 S A 1150 GL Comet Zero 2 S A 1250 GL x Contender 1 U 0 976 GL D-One 1 U A 971 GL D-Zero 1 U 0 1033 2 GL D-Zero Blue 1 U 0 1061 2 GL Enterprise 2 S 0 1145 3 GL Europe 1 U 0 1145 -3 GL Farr 3.7 1 U 0 1053 38 GL Finn 1 U 0 1042 GL Fire 1 U 0 1050 GL Fireball 2 S C 948 -5 GL Firefly 2 S 0 1190 GL Flash 1 U 0 1101 GL Fleetwind 2 S 0 1268 GL x Flying Dutchman 2 S C 879 -1 GL GP14 2 S C 1131 1 GL Graduate 2 S 0 1132 -4 GL Hadron 1 U 0 1040 GL Halo 1 U 0 1010 GL Heron 1 S 0 1345 GL x Hornet 2 S C 962 -1 GL Icon 2 S 0 990 GL Int 14 2 S A 700 -20 GL Int Canoe 1 S 0 893 GL Int Canoe - Asym 1 S A 840 GL Int Lightning 3 S C 980