CPA DPSG Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report

INTERIM REPORT ON ELECTION-RELATED VIOLENCE: GENERAL ELECTION 2004 2ND APRIL 2004 Election Day Violations Figure 1 COMPARISON OF ELECTION DAY INCIDENTS: ELECTION DAY 2004 WITH A) POLLING DAY - PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 1999 B) POLLING DAY - GENERAL ELECTION 2001 General A Election B 2004 General Election 368 incidents 2004 (20%) 368 incidents (27%) Presidential Election 1999 General 973 incidents (73%) Election 2001 1473 (80%) Total number of incidents in both elections 1341 Total number of incidents in both elections 1841 2004 General Election Campaign Source: Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) Releases and Reports are signed by the three Co-Convenors, Ms. Sunila Abeysekera, Mr Sunanda Deshapriya and Dr Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu. CMEV Monitors sign a pledge affirming their commitment to independent, non partisan monitoring and are trained before deployment. In addition to local Monitors at all levels, CMEV also deploys International Observers to work with its local Monitors in the INTERIM REPORT field, two weeks to ten days before polling day and on polling day. International Observers are recruited from international civil society organizations and have worked in the human rights and nd ELECTION DAY 2 APRIL 2004 development fields as practitioners, activists and academics. The Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) was On Election Day, CMEV deployed 4347 Monitors including 25 formed in 1997 by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), the International Observers. CMEV monitored a total of 6,215 Free Media Movement (FMM) and the Coalition Against Political polling centres or 58.2% of the total of 10,670 polling centres. Violence as an independent non-partisan organization to monitor the incidence of election – related violence. -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

Provisional Record 8 99Th Session, Geneva, 2010

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 8 99th Session, Geneva, 2010 Third sitting Thursday, 10 June 2010, 10.10 a.m. Presidents: Mr de Robien and Mr Nakajima support of more than 160 countries, the UN Eco- PRESENTATION OF THE REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON nomic and Social Council adopted the resolution, OF THE GOVERNING BODY “Recovering from the crisis: A Global Jobs Pact”. If employment and social protection were to be the Original French: The PRESIDENT (Mr DE ROBIEN) drivers and ultimate purposes of the recovery, the We will begin our work with the presentation of Pact had to be streamlined into the multilateral sys- the report of the Chairperson of the Governing tem. What was born as a portfolio of concrete Body to the Conference for the year 2009–10. The measures had to become an international reference. report is published in Provisional Record No. 1. It had to be an inspiration to a more sustainable I now give the floor to Ms Farani Azevêdo, economy and a more democratic and legitimate in- Chairperson of the Governing Body. After her pres- ternational order. As was stated last November by entation, I will give the floor to the spokespersons Minister Celso Amorim of Brazil in the Working of the groups and open the general discussion. Party on the Social Dimension of Globalization, a Ms AZEVÊDO (Chairperson of the Governing Body of the new and more inclusive global governance is re- International Labour Office) quired to protect the most vulnerable members of I would like first to recall that tomorrow is the society. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 70. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, May 18, 2016 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and the Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 70 Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis and Western Development Hon. Chandima Weerakkody, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. -

ABBN-Final.Pdf

RESTRICTED CONTENTS SERIAL 1 Page 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Sri Lanka Army a. Commands 5 b. Branches and Advisors 5 c. Directorates 6 - 7 d. Divisions 7 e. Brigades 7 f. Training Centres 7 - 8 g. Regiments 8 - 9 h. Static Units and Establishments 9 - 10 i. Appointments 10 - 15 j. Rank Structure - Officers 15 - 16 k. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 16 l. Courses (Local and Foreign) All Arms 16 - 18 m. Course (Local and Foreign) Specified to Arms 18 - 21 SERIAL 2 3. Reference Points a. Provinces 22 b. Districts 22 c. Important Townships 23 - 25 SERIAL 3 4. General Abbreviations 26 - 70 SERIAL 4 5. Sri Lanka Navy a. Commands 71 i RESTRICTED RESTRICTED b. Classes of Ships/ Craft (Units) 71 - 72 c. Training Centres/ Establishments and Bases 72 d. Branches (Officers) 72 e. Branches (Sailors) 73 f. Branch Identification Prefix 73 - 74 g. Rank Structure - Officers 74 h. Rank Structure - Other Ranks 74 SERIAL 5 6. Sri Lanka Air Force a. Commands 75 b. Directorates 75 c. Branches 75 - 76 d. Air Force Bases 76 e. Air Force Stations 76 f. Technical Support Formation Commands 76 g. Logistical and Administrative Support Formation Commands 77 h. Training Formation Commands 77 i. Rank Structure Officers 77 j. Rank Structure Other Ranks 78 SERIAL 6 7. Joint Services a. Commands 79 b. Training 79 ii RESTRICTED RESTRICTED INTRODUCTION USE OF ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS AND INITIALISMS 1. The word abbreviations originated from Latin word “brevis” which means “short”. Abbreviations, acronyms and initialisms are a shortened form of group of letters taken from a word or phrase which helps to reduce time and space. -

A Study on Sri Lanka's Readiness to Attract Investors in Aquaculture With

A Study on Sri Lanka’s readiness to attract investors in aquaculture with a focus on marine aquaculture sector Prepared by RR Consult, Commissioned by Norad for the Royal Norwegian Embassy, Colombo, Sri Lanka Sri Lanka’s readiness to attract investors in aquaculture TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 6 Background and scope of study .............................................................................................................. 8 Action plan - main findings and recommendations ................................................................................ 8 Ref. Annex 1: Regulatory, legal and institutional framework conditions related aquaculture ...... 9 Ref. Chapter I: Aquaculture related acts and regulations ............................................................... 9 Ref. Chapter II: Aquaculture policies and strategies ..................................................................... 10 Ref. Chapter III: Aquaculture application procedures ................................................................. 10 Ref. Chapter IV: Discussion on institutional framework related to aquaculture ......................... 11 Ref. Chapter V: Environmental legislation ................................................................................... -

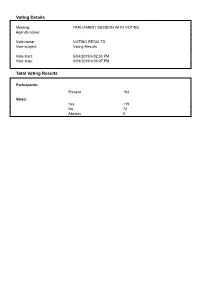

Voting Details Total Voting Results

Voting Details Meeting: PARLIAMENT SESSION WITH VOTING Agenda name: Vote name: VOTING RESULTS Vote subject: Voting Results Vote start: 5/04/2019 6:02:50 PM Vote stop: 5/04/2019 6:05:07 PM Total Voting Results Participants: Present 193 Votes: Yes 119 No 74 Abstain 0 Individual Voting Results OPPOSITION SIDE O 002. Sumedha G. Jayasena No O 003. W.D.J. Senewiratne No O 004. S.B. Dissanayake No O 005. Dinesh Gunawardana No O 007. Chamal Rajapaksa No O 008. Mahinda Rajapaksa No O 011. Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi No O 013. Wimal Weerawansa No O 015. A.D. Susil Premajayantha No O 016. Gamini Lokuge No O 018. Mavai S. Senathirajah Yes O 019. Anura Dissanayake No O 022. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa No O 023. Bandula Gunawardana No O 026. Janaka Bandara Tennakoon No O 027. C.B. Ratnayake No O 028. Muthu Sivalingam Yes O 029. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena No O 030. Dilan Perera No O 031. Keheliya Rambukwella No O 032. Kumara Welgama No O 033. Dullas Alahapperuma No O 034. Johnston Fernando No O 036. T.B. Ekanayake No O 037. Dharmalingam Sithadthan Yes O 039. Nihal Galappaththi No O 040. Vijitha Herath No O 041. S.M. Chandrasena No O 042. Mahindananda Aluthgamage No O 044. Piyankara Jayaratne No O 045. Vasudeva Nanayakkara No O 046. Lakshman Yapa Abeywardene No O 048. Rohitha Abeygunawardana No O 050. Chandima Weerakkody No O 053. Udaya Prabhath Gammanpila No O 054. Susantha Punchinilame No O 057. K. Thurairetnasingam Yes O 058. Seeniththamby Yoheswaran Yes O 059. -

Friday 18 September 2020 6-Minute Talk with Latest Edition Harin’S Father Vol: 09/234 Price : Rs 30.00 by Buddhika Samaraweera and W.K

The day before Easter attacks CID Officer had FRIDAY 18 september 2020 6-minute talk with LATEST EDITION Harin’s father VOL: 09/234 PRICE : Rs 30.00 BY BUDDHIKA SAMARAWEERA AND W.K. In Sports PRASAD MANJU President discusses A six-minute-long telephone conversation had development taken place between an officer attached to the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) and of country’s sports Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) National List MP President Gotabaya Rajapaksa met Harin Fernando's father, Nihal Fernando on 20 Minister of Sports and Youth affairs April 2019, the day before Easter Sunday attacks Namal Rajapaksa, former Sri Lanka last year,... skipper Kumar Sangakkara and others for a discussion on Wednesday (16), regarding the country’s sports. Story Continued on PAGE 2 A16 Notice Issued on MT Diamond’s Skipper Charges include failure to adopt safety measures SL to Withdraw BY HANSI NANAYAKKARA He further said, following an Colombo Additional order obtained from the Court Magistrate Priyantha Liyanage at the previous hearing, yesterday (17), issued notice statements had been recorded from UNHRC on the Captain of the ‘MT New from four persons, including Diamond’ oil tanker to appear the Captain of the ship and BY THAMEENAH RAZEEK before him on 28 September. observed that more He issued the notice on the statements had to be recorded While concurring with the position that Sri Lanka should Captain of the distressed oil from a few more crew pull out from the United Nations Human Rights Council tanker, following a request members. (UNHRC), Cabinet Spokesman Keheliya Rambukwella made to Court by Deputy The prosecution told the said, Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena Solicitor General Dileepa Additional Magistrate that informing the UNHRC of the withdrawal from the Peiris, who sought to name from the statement recorded co-sponsorship of Resolution 30/1 was the initial the Captain as a suspect in from the Captain, he had step in the process. -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka May 2007

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 11 MAY 2007 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 11 MAY 2007 SRI LANKA Contents PREFACE Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 APRIL 2007 TO 30 APRIL 2007 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 AND 30 APRIL 2007 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources.............................................................................. 4.21 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

Cluster Report

MONITORING FACTORS AFFECTING THE SRI LANKAN PEACE PROCESS CLUSTER REPORT THIRD QUARTERLY MAY 2008 – JULY 2008 CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES TABLE OF CONTENTS CLUSTER Page Number PEACE TALKS AND NEGOTIATIONS CLUSTER ……………………………………… 2 MILITARY BALANCE CLUSTER ........................................................................................................3 HUMAN SECURITY....................................................................................................................................7 POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT CLUSTER .....................................................................................11 INTERNATIONAL CLUSTER ............................................................................................................15 LEGAL & CONSTIIUTIONAL CLUSTER .....................................................................................18 ECONOMIC CLUSTER ..........................................................................................................................21 PUBLIC OPINION CLUSTER ............................................................................................................26 MEDIA ...........................................................................................................................................................30 ENDNOTES…..……………………………………………………………………………….34 METHODOLOGY The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) has conducted the project “Monitoring the Factors Affecting the Peace Process” to provide an understanding of the current status of the peace -

YS% ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;S%L Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 1"991 – 2016 Tlaf;dan¾ ui 28 jeks isl=rdod – 2016'10'28 No. 1,991 – fRiDAy, OCtOBER 28, 2016 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be filed separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifications … … 1204 Appointments, &c., by the President … 1128 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … — Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 1206 Other Appointments, &c. … … 1192 Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– (i) Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 12, 2016. (ii) Nation Building tax (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of August 19, 2016. (iii) Land (Restrictions on Alienation) (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the part ii of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of September 02, 2016. IMportant NOTICE REGARDING Acceptance OF NOTICES FOR PUBlication IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” AttENtiON is drawn to the Notification appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10