What a History of Tax Withholding Tells Us About the Relationship Between Statutes and Constitutional Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tearing out the Income Tax by the (Grass)Roots

FLORIDA TAX REVIEW Volume 15 2014 Number 8 TEARING OUT THE INCOME TAX BY THE (GRASS)ROOTS by Lawrence Zelenak* Rich People’s Movements: Grassroots Campaigns to Untax the One Percent. By Isaac William Martin New York: Oxford University Press. 2013. I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 649 II. A CENTURY OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS ......... 651 III. EXPLAINING THE SUPPORT OF THE NON-RICH .......................... 656 IV. BUT WHAT ABOUT THE FLAT TAX AND THE FAIRTAX? ............ 661 V. THE RHETORIC OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS: PARANOID AND NON-PARANOID STYLES .................................... 665 VI. CONCLUSION ................................................................................. 672 I. INTRODUCTION Why do rich people seeking reductions in their tax burdens, who have the ability to influence Congress directly through lobbying and campaign contributions, sometimes resort to grassroots populist methods? And why do non-rich people sometimes join the rich in their anti-tax movements? These are the puzzles Isaac William Martin sets out to solve in Rich People’s Movements.1 Martin’s historical research—much of it based on original sources to which scholars have previously paid little or no attention—reveals that, far from being a recent innovation, populist-style movements against progressive federal taxation go back nearly a century, to the 1920s. Although Martin identifies various anti-tax movements throughout the past century, he strikingly concludes that there has been “substantial continuity from one campaign to the next, so that, in some * Pamela B. Gann Professor of Law, Duke Law School. 1. ISAAC WILLIAM MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS: GRASSROOTS CAMPAIGNS TO UNTAX THE ONE PERCENT (2013) [hereinafter MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS]. -

A Brief Description of Federal Taxes

A BRIEF DESCRIFTION OF FEDERAL TAXES ON CORPORATIONS SINCE i86i WMUAu A. SU. ND* The cost to the federal government of financing the Civil War created a need for increased revenue, and Congress in seeking new sources tapped theretofore un- touched corporate and individual profits. The Act of July x, x862, amending the Act of August 5, x86i, is the first law under which any federal income tax was collected and is considered to be largely the basis of our present system of income taxation. The tax acts of the Civil War period contained provisions imposing graduated taxes upon the gain, profits, or income of every person2 and providing that corporate profits, whether divided or not, should be taxed to the stockholders. Certain specified corporations, such as banks, insurance companies and transportation companies, were taxed at the rate of 5%, and their stockholders were not required to include in income their pro rata share of the profits. There were several tax acts during and following the War, but a description of the Act of 1864 will serve to show the general extent of the coiporate taxes of that period. The tax or "duty" was imposed upon all persons at the rate of 5% of the amount of gains, profits and income in excess of $6oo and not in excess of $5,000, 7Y2/ of the amount in excess of $5,ooo and not in excess of -$o,ooo, and io% of the amount in excess of $Sxooo.O This tax was continued through the year x87i, but in the last two years of its existence was reduced to 2/l% upon all income. -

The Death of the Income Tax (Or, the Rise of America's Universal Wage

Indiana Law Journal Volume 95 Issue 4 Article 5 Fall 2000 The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax) Edward J. McCaffery University of Southern California;California Institute of Tecnology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Taxation-Federal Commons, Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons, Taxation-State and Local Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation McCaffery, Edward J. (2000) "The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax)," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 95 : Iss. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol95/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Death of the Income Tax (or, The Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax) EDWARD J. MCCAFFERY* I. LOOMINGS When Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, just weeks into her tenure as America’s youngest member of Congress, floated the idea of a sixty or seventy percent top marginal tax rate on incomes over ten million dollars, she was met with a predictable mixture of shock, scorn, and support.1 Yet there was nothing new in the idea. AOC, as Representative Ocasio-Cortez is popularly known, was making a suggestion with sound historical precedent: the top marginal income tax rate in America had exceeded ninety percent during World War II, and stayed at least as high as seventy percent until Ronald Reagan took office in 1981.2 And there is an even deeper sense in which AOC’s proposal was not as radical as it may have seemed at first. -

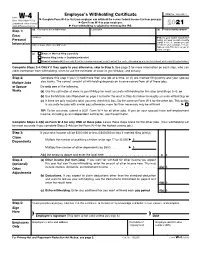

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Sixteenth Amendment

The Sixteenth Amendment 100 Years of the Federal Income Tax “The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax.” ~ Albert Einstein Americans have now been grappling with the income tax for 100 years. Since the 16th Amendment was ratified by Congress in 1913, U.S. citizens have been attempting to accurately complete Form 1040. While the annual income tax exercise is fresh in our minds, we thought it would be informative and somewhat gratifying to look back at the process that brought us here, and the tax rates that confronted tax payers on this anniversary in prior years. History of the Sixteenth Amendment Prior to 1913, the main source of revenue for the federal government was tariffs. Tariffs, it was argued, disproportionately affected the poor and were unpredictable. It was felt by many that the solution was a federal income tax. The resolution proposing the Sixteenth Amendment was passed by Congress on July 12, 1909 and ratified in 1913. The Amendment stated “Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” What followed was The Revenue Act of 1913, also called the Tariff Act, since its purpose was to lower basic tariff rates and compensate for lost revenues by imposing a federal income tax. The first tax filing in 1914 The federal income tax started at 1% on personal income of more than $3,000 (over $71,000 in today’s dollars1) for single filers or $4,000 for couples, with a surtax of 6% on incomes over $500,000. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

The Joint Committee on Taxation and Codification of the Tax Laws

The Joint Committee on Taxation and Codification of the Tax Laws George K. Yin Edwin S. Cohen Distinguished Professor of Law and Taxation University of Virginia Former Chief of Staff, Joint Committee on Taxation February 2016 Draft prepared for the United States Capitol Historical Society’s program on The History and Role of the Joint Committee: the Joint Committee and Tax History Comments welcome. THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE JCT@90 WASHINGTON, DC FEBRUARY 25, 2016 The Joint Committee on Taxation and Codification of the Tax Laws George K. Yin* February 11, 2016 preliminary draft [Note to conference attendees and other readers: This paper describes the work of the staff of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation (JCT)1 that led to codification of the tax laws in 1939. I hope eventually to incorporate this material into a larger project involving the “early years” of the JCT, roughly the period spanning the committee’s creation in 1926 and the retirement of Colin Stam in 1964. Stam served on the staff for virtually this entire period; he was first hired (on a temporary basis) in 1927 as assistant counsel, became staff counsel in 1929, and then served as Chief of Staff from 1938 until 1964. He is by far the longest‐serving Chief of Staff the committee has ever had. The conclusions in this draft are still preliminary as I have not yet completed my research. I welcome any comments or questions.] Possibly the most significant accomplishment of the JCT and its staff during the committee’s “early years” was the enactment of the Internal Revenue Code of 1939. -

Publication 509, Tax Calendars

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P509/2021/A/XML/Cycle13/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 13 10:55 - 31-Dec-2020 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 509 Cat. No. 15013X Contents Introduction .................. 2 Department of the Tax Calendars Background Information for Using Treasury the Tax Calendars ........... 2 Internal Revenue General Tax Calendar ............ 3 Service First Quarter ............... 3 For use in Second Quarter ............. 4 2021 Third Quarter ............... 4 Fourth Quarter .............. 5 Employer's Tax Calendar .......... 5 First Quarter ............... 6 Second Quarter ............. 7 Third Quarter ............... 7 Fourth Quarter .............. 8 Excise Tax Calendar ............. 8 First Quarter ............... 8 Second Quarter ............. 9 Third Quarter ............... 9 Fourth Quarter ............. 10 How To Get Tax Help ........... 12 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 509, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub509. What’s New Payment of deferred employer share of so- cial security tax from 2020. If the employer deferred paying the employer share of social security tax in 2020, pay 50% of the employer share of social security tax by January 3, 2022 and the remainder by January 3, 2023. Any payments or deposits you make before January 3, 2022, are first applied against the first 50% of the deferred employer share of social security tax, and then applied against the remainder of your deferred payments. Payment of deferred employee share of so- cial security tax from 2020. -

Misc Publications MP-02

TAX FOUNDATION, INC. 50 Rockefeller Plaz a New York, N. Y. August 15, 1940 1 FORMM This conrpilation and bibliography are presented in th e hone that they will contribute to a fuller understanding of a difficult and at times controversial subject . In selecting the materials included an effort was made to obtain a cross section of opinions cnnd points of view . Attention is directed to the bibliograpay of periodical and special materials on war, profit s and excess profits thxation issued from 1916 to 1940. In the light of recent event s, the body of literature developed as P. result of our experience with those forms of taxation during and immodiately after the War of 1914--1919 has assumed anew significance . August 15, 1940 xA FOUIMATION 0 At Page Current Proposals 1 Some Aspects of the Profit-Tax Bill 2 The Excess-Profits Tart 3 Taxation and National Defense 4 Holding Up Defense 5 Excess-Profit Tax Hinges on Business 6 The Revenue Angle 7 The Basis 11or An Excess-Profits Tax 9 The Valuation cf Business Investments 9 Effects of Excess Profits Taxes 1 0 Excess Profits Tax : A Wartime Measure 11 Excess Profits Taxes, 1933 o 1940 1 2 The World War and Postwar Pederal :Taxation 1 3 Wartime Taxes on Profits 14 LIST OF TABLE S National Defense Expenditures, Fiscal Years 1928-1941 15 Taxes, Not Income and Dividends of All Activ e Corporations in the United States 16 Effects of Tax Increases 1 7 Table Showing 7,899 Representative Corporations Classified According to Amount of Invested Capital and R :titio of Net Income to Invested Capital During tho Taxable Year 18 Excess-Profits Taxes of Twelve Coal Companies 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY :Bibliographer on Par Profits and Excoss Profits Taxos 20 1 . -

The Progressive Movement and the Reforming of the United States of America, from 1890 to 1921

2014 Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria. Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. University of Oran. Faculty of Letters, Languages, and Arts. Department of English. Research Paper Submitted for a Doctorate Thesis in American Civilisation Entitled: The Progressive Movement and the Reforming of the United States of America, from 1890 to 1921. Presented by: Benketaf, Abdel Hafid. Jury Members Designation University Pr. Bouhadiba, Zoulikha President Oran Pr. Borsali, Fewzi Supervisor Adrar Pr. Bedjaoui, Fouzia Examiner 1 Sidi-Belabes Dr. Moulfi, Leila Examiner 2 Oran Dr. Belmeki, Belkacem Examiner 3 Oran Dr. Afkir, Mohamed Examiner 4 Laghouat Academic Year: 2013-2014. 1 Acknowledgements Acknowledgments are gratefully made for the assistance of numerous friends and acquaintances. The largest debt is to Professor Borsali, Fewzi because his patience, sound advice, and pertinent remarks were of capital importance in the accomplishment of this thesis. I would not close this note of appreciation without alluding to the great aid provided by my wife Fatima Zohra Melki. 2 Dedication To my family, I dedicate this thesis. Pages Contents 3 List of Tables. ........................................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Abbreviations......................................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction. ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Re-Assessing the Costs of the Stepped-Up Tax Basis Rule

Tulane Economics Working Paper Series Re-assessing the Costs of the Stepped-up Tax Basis Rule Jay A. Soled Richard L. Schmalbeck James Alm Rutgers Business School Duke Law School Tulane University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Working Paper 1904 April 2019 Abstract The stepped-up basis rule applicable at death (IRC section 1014) has always been a major source of revenue loss. Now, in the absence of a meaningful estate tax regime, taxpayers and their estate executors and administrators are likely to report inated date-of-death asset values. As a result, the revenue loss associated with this tax expenditure, called the stepped-up tax basis rule, will surely increase markedly. The Internal Revenue Service will no doubt attempt to police excessive tax basis adjustments, but the agency lacks the resources to do so adequately. Congress should therefore institute reforms to ensure proper tax basis identication. Keywords: Estate tax, capital gains, stepped-up basis tax rule. JEL codes: H2, H3. RE-ASSESSING THE COSTS OF THE STEPPED-UP TAX BASIS RULE Jay A. Soled, Richard L. Schmalbeck, & James Alm* The stepped-up basis rule applicable at death (IRC section 1014) has always been a major source of revenue loss. Now, in the absence of a meaningful estate tax regime, taxpayers and their estate executors and administrators are likely to report inflated date- of-death asset values. As a result, the revenue loss associated with this tax expenditure, called the “stepped-up tax basis rule”, will surely increase markedly. The Internal Revenue Service will no doubt attempt to police excessive tax basis adjustments, but the agency lacks the resources to do so adequately. -

Publication 517, Social Security

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P517/2020/A/XML/Cycle03/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 18 11:42 - 2-Mar-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 517 Cat. No. 15021X Contents Future Developments ............ 1 Department of the Social Security What's New .................. 1 Treasury Internal Reminders ................... 2 Revenue and Other Service Introduction .................. 2 Information for Social Security Coverage .......... 3 Members of the Ministerial Services ............. 4 Exemption From Self-Employment Clergy and (SE) Tax ................. 6 Self-Employment Tax: Figuring Net Religious Earnings ................. 7 Income Tax: Income and Expenses .... 9 Workers Filing Your Return ............. 11 Retirement Savings Arrangements ... 11 For use in preparing Earned Income Credit (EIC) ....... 12 Worksheets ................. 14 2020 Returns How To Get Tax Help ........... 15 Index ..................... 18 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 517, such as legislation enacted after this publication was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub517. What's New Tax relief legislation. Recent legislation pro- vided certain tax-related benefits, including the election to use your 2019 earned income to fig- ure your 2020 earned income credit. See Elec- tion to use prior-year earned income for more information. Credits for self-employed individuals. New refundable credits are available to certain self-employed individuals impacted by the coro- navirus. See the Instructions for Form 7202 for more information. Deferral of self-employment tax payments under the CARES Act. The CARES Act al- lows certain self-employed individuals who were affected by the coronavirus and file Schedule SE (Form 1040), to defer a portion of their 2020 self-employment tax payments until 2021 and 2022.