Cross-Border Planning for Canadian Registered Retirement Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

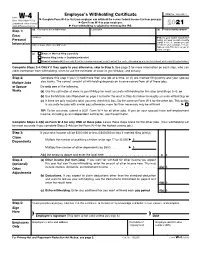

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Publication 509, Tax Calendars

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P509/2021/A/XML/Cycle13/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 13 10:55 - 31-Dec-2020 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 509 Cat. No. 15013X Contents Introduction .................. 2 Department of the Tax Calendars Background Information for Using Treasury the Tax Calendars ........... 2 Internal Revenue General Tax Calendar ............ 3 Service First Quarter ............... 3 For use in Second Quarter ............. 4 2021 Third Quarter ............... 4 Fourth Quarter .............. 5 Employer's Tax Calendar .......... 5 First Quarter ............... 6 Second Quarter ............. 7 Third Quarter ............... 7 Fourth Quarter .............. 8 Excise Tax Calendar ............. 8 First Quarter ............... 8 Second Quarter ............. 9 Third Quarter ............... 9 Fourth Quarter ............. 10 How To Get Tax Help ........... 12 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 509, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub509. What’s New Payment of deferred employer share of so- cial security tax from 2020. If the employer deferred paying the employer share of social security tax in 2020, pay 50% of the employer share of social security tax by January 3, 2022 and the remainder by January 3, 2023. Any payments or deposits you make before January 3, 2022, are first applied against the first 50% of the deferred employer share of social security tax, and then applied against the remainder of your deferred payments. Payment of deferred employee share of so- cial security tax from 2020. -

Publication 517, Social Security

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P517/2020/A/XML/Cycle03/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 18 11:42 - 2-Mar-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 517 Cat. No. 15021X Contents Future Developments ............ 1 Department of the Social Security What's New .................. 1 Treasury Internal Reminders ................... 2 Revenue and Other Service Introduction .................. 2 Information for Social Security Coverage .......... 3 Members of the Ministerial Services ............. 4 Exemption From Self-Employment Clergy and (SE) Tax ................. 6 Self-Employment Tax: Figuring Net Religious Earnings ................. 7 Income Tax: Income and Expenses .... 9 Workers Filing Your Return ............. 11 Retirement Savings Arrangements ... 11 For use in preparing Earned Income Credit (EIC) ....... 12 Worksheets ................. 14 2020 Returns How To Get Tax Help ........... 15 Index ..................... 18 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 517, such as legislation enacted after this publication was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub517. What's New Tax relief legislation. Recent legislation pro- vided certain tax-related benefits, including the election to use your 2019 earned income to fig- ure your 2020 earned income credit. See Elec- tion to use prior-year earned income for more information. Credits for self-employed individuals. New refundable credits are available to certain self-employed individuals impacted by the coro- navirus. See the Instructions for Form 7202 for more information. Deferral of self-employment tax payments under the CARES Act. The CARES Act al- lows certain self-employed individuals who were affected by the coronavirus and file Schedule SE (Form 1040), to defer a portion of their 2020 self-employment tax payments until 2021 and 2022. -

Publication 523 Reminders

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 10 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P523/2020/A/XML/Cycle04/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 22 12:06 - 1-Mar-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Department of the Treasury Contents Internal Revenue Service Future Developments ....................... 1 Publication 523 Reminders ............................... 1 Cat. No. 15044W Introduction .............................. 2 Does Your Home Sale Qualify for the Exclusion of Gain? .............................. 2 Selling Eligibility Test ........................... 3 Does Your Home Qualify for a Partial Your Home Exclusion of Gain? ...................... 6 Figuring Gain or Loss ....................... 7 For use in preparing Basis Adjustments—Details and Exceptions ..... 8 Business or Rental Use of Home ............ 11 Returns 2020 How Much Is Taxable? ..................... 14 Recapturing Depreciation ................. 15 Reporting Your Home Sale .................. 15 Reporting Gain or Loss on Your Home Sale .... 16 Reporting Deductions Related to Your Home Sale ............................... 17 Reporting Other Income Related to Your Home Sale .......................... 17 Paying Back Credits and Subsidies .......... 18 How To Get Tax Help ...................... 18 Index .................................. 22 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 523, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub523. Reminders Photographs of missing children. The IRS is a proud partner with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children® (NCMEC). Photographs of missing children se- lected by the Center may appear in this publication on pa- ges that would otherwise be blank. You can help bring these children home by looking at the photographs and calling 800-THE-LOST (800-843-5678) if you recognize a child. -

Pub 515, Withholding of Tax on Nonresident Aliens and Foreign

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P515/2021/A/XML/Cycle05/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 56 16:15 - 3-Feb-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 515 Cat. No. 15019L Contents What's New .................. 1 Department of the Withholding Reminders ................... 2 Treasury Internal Introduction .................. 2 Revenue of Tax on Service Withholding of Tax .............. 3 Nonresident Persons Subject to Chapter 3 or Chapter 4 Withholding ......... 5 Aliens and Documentation ............... 10 Foreign Entities Income Subject to Withholding ..... 23 Withholding on Specific Income ..... 26 Foreign Governments and Certain Other Foreign Organizations .... 39 For use in 2021 U.S. or Foreign TINs ............ 40 Depositing Withheld Taxes ........ 41 Returns Required .............. 42 Partnership Withholding on Effectively Connected Income ... 43 Section 1446(f) Withholding ....... 46 U.S. Real Property Interest ........ 48 Definitions .................. 51 Tax Treaties ................. 52 How To Get Tax Help ........... 52 Index ..................... 55 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 515, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub515. What's New New requirement to fax requests for exten- sion to furnish statements to recipients. Requests for an extension of time to furnish cer- tain statements to recipients, including Form 1042-S, should now be faxed to the IRS. For more information see Extension to furnish state- ments to recipients under Extensions of Time To File, later. COVID-19 relief for Form 8233 filers. The IRS has provided relief from withholding on compensation for certain dependent personal services, for individuals who were unable to leave the United States due to the global health Get forms and other information faster and easier at: emergency caused by COVID-19. -

2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns

2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide For 2020 Returns A Supplement to the 2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns For the 2020 tax year, the Church Pension Group (CPG) is providing the 2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns and the 2021 Federal Reporting Requirements for Episcopal Churches, Schools, and Institutions (Federal Reporting Requirements Guide) as references to help clergy, treasurers and bookkeepers, and tax preparers in better understanding clergy taxes. These guides are available on CPG’s website at cpg.org. This supplement complements the guides. The supplement is presented in two sections. First, a section on tax highlights addresses recent tax changes. Second, a question-and-answer format addresses key tax issues, and information provided in the guides and how it specifically applies to clergy of The Episcopal Church. Note: If you have questions about clergy federal income taxes that are not covered here, please call CPG’s Tax Hotline: Nancy Fritschner, CPA (877) 305-1414 Mary Ann Hanson, CPA (877) 305-1415 Dolly Rios,* CPA (833) 363-5751 *Fluent in English and Spanish Please note that the service these individuals will provide is of an informational nature. It should not be viewed as tax, legal, financial, or other advice. You must contact your tax advisor for assistance in preparing your tax returns or for other tax advice. Tax Highlights The SECURE (Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement) Act of 2019 is now law. Most provisions in the law became effective January 1, 2020. Listed below are some of the most important changes that could have a significant impact on you. -

Guide to Kansas Withholding Tax (KW-100)

Withholding Tax Guide NEW WITHHOLDING TAX RATES for wages paid on or after January 1, 2021 ksrevenue.org KW-100 (Rev. 6-21) TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO KANSAS WITHHOLDING TAX .... 3 KANSAS CUSTOMER SERVICE CENTER ................... 8 Who Must Withhold Kansas Income Tax? File, Pay and Make Updates Electronically Who are Employees/Payees? What Can I Do Electronically Sole Proprietors and Partners Requirements to File and Pay Pay by Credit Card PAYMENTS SUBJECT TO KANSAS WITHHOLDING .. 3 Wire Transfers Wages Record Keeping Supplemental Wages Filing Frequencies and Due Dates Fringe Benefits Completing a KW-5 Deposit Report Cafeteria, 401K, and Profit-Sharing Plans Correcting a KW-5 Deposit Report Payments Other Than Wages ANNUAL RETURNS AND FORMS .............................. 12 Pensions, Annuities & Deferred Income Interest and Dividends Completing a Withholding Tax Return (KW-3) Lottery and Gambling Winnings Wage and Tax Statements (W-2) Annual Information Returns (1099 and 1096) WITHHOLDING REGISTRATION ................................... 4 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ...................................... 13 Who Must Register How and When to Register When Returns are Late Your Kansas Tax Account Number Employer/Payer and Officer Liability Your Registration Certificate About Our Billing Process Reporting Business Changes HOW TO WITHHOLD KANSAS TAX ............................. 5 Changing Your Filing Frequency Kansas Withholding Allowance Certificate Closing Your Withholding Account Additional Kansas Withholding When in Doubt… Exclusion -

Review of Key "Deoffshorization" Concepts in Russia Taxation of Controlled Foreign Companies 03

Review of key "deoffshorization" concepts in Russia Taxation of controlled foreign companies 03 Taxation of Russian tax resident foreign companies 08 Definition of beneficial owner of passive income 09 Taxation of capital gains from indirect sale of Russian-based real estate 10 Review of key "deoffshorization" concepts in Russia The Russian “deoffshorization” agenda • this person has decisive influence over Apart from settlors/founders, any sets the new rules for taxation of foreign the company’s decisions regarding its other person that exercises control entities’ income. This publication profit distributions. over a foreign non-legal entity provides an overview of the rules. (i.e. has a decisive influence over profit An individual or an entity will not be distribution decisions) may be treated Taxation of controlled foreign recognized as a controlling person as a controlling person if at least one companies of a foreign company, if this person’s of the following conditions is met: Under the controlled foreign direct and/or indirect interest companies (the “CFC”) rules, a tax in the company is held exclusively via • The person is a beneficial owner on the CFC’s undistributed profits may a Russian public company (companies). of the entity’s income; be charged to its controlling person at 13% (if the controlling person A settlor/founder of a non-legal entity • The person is entitled to dispose is a Russian tax resident individual) is normally deemed a controlling person of the entity’s property; or 20% (if the controlling person of such entity. However, the settlor/ is a Russian tax resident organization). -

State Guidance Related to COVID-19: Telecommuting Issues Updated Last on June 9, 2021

State Guidance Related to COVID-19: Telecommuting Issues Updated last on June 9, 2021 State Nexus imposed State Guidance What state gets to tax the State Guidance due to income of a telecommuter? telecommuting? Alabama No The Alabama DOR issued guidance that Employee’s regular place of “Alabama will not change withholding requirements “Alabama will not consider temporary work (i.e., the employer’s home for businesses based on an employee’s temporary changes in an employee’s physical work state) telework location within Alabama that is location during periods in which temporary necessitated by the pandemic and related federal or telework requirements are in place due to state measures to control its spread.” AL DOR, the pandemic to impose nexus or alter Alabama Department of Revenue Coronavirus apportionment of income for any business.” (COVID-19) Updates AL DOR, Alabama Department of Revenue Coronavirus (COVID-19) Updates Alaska Yes Checkpoint surveyed all 50 states, and the No state income tax Alaska DOR replied that “Alaska does not (for corporate have any de minimis standard or exception income tax) provided in statute or regulation, so an employee whose compensation is assignable to Alaska under 15 AAC 19.241 would create nexus for that business entity.” (Email on File with Checkpoint Catalyst, 05/18/2020.) Arizona No Checkpoint surveyed all 50 states, and the No guidance Arizona DOR replied that the agency “has (for corporate determined that in general, there is no income tax) requirement to waive nexus” for corporate privilege tax. -

Withholding and Reporting of Tax on Wage Payments to Foreign Persons

Federal Agency Seminar 2011 Withholding and Reporting of Tax on Wage Payments to Foreign Persons 1 Objectives • Know why tax residency is important • Which income non-resident alien are subject to FIT withholding • Introduce the special W-4 rules • Know that non-resident aliens are subject to FICA tax 2 Income from independent personal services… • Provided by a Non-Resident Alien is generally subject to 30% withholding for self employment income per Code § 1441 3 Income for personal services qualify as wages when… • There is an employer-employee relationship • Individual who performs the services subject to the will and control of an employer • Employer has the legal right to control both the method and the result • This is call dependent personal services 4 Tax Residency • Resident Alien • Non-Resident Alien • Dual-Status Taxpayer 5 Tax residency is based on… • Green Card Test – A lawful permanent resident of the U.S. • Substantial Presence Test – Numerical formula for counting days of presence in the U.S. over a 3 year period 7 Exempt Individuals from the SPT • 5-calendar-year non-resident rule for students. They are individuals typically issued an F, J, M or Q visa • 2/7-calendar-year nonresident rule for teachers and trainees 8 Why tax residency? • A resident alien is a U.S. Person, and is usually taxed the same as a U.S. citizen on their worldwide income • A nonresident alien is a Foreign Person, and is subject to special rules of taxation on their U.S. source income 9 Source Rules on Fringe Benefits • Housing – EE's main job location -

8. Taxation 8.1 Introduction Over the Past 16 Years Russia Has Been Engaged in a Significant Reform of Its Tax System, Which Has Been Implemented in Phases

Doing Business in Russia 8. Taxation 8.1 Introduction Over the past 16 years Russia has been engaged in a significant reform of its tax system, which has been implemented in phases. This reform has improved procedural rules and made them more favorable to taxpayers, has reduced the overall number of taxes, and has reduced the overall tax burden in the country. Part I of the Tax Code of the Russian Federation (the “Tax Code”) came into effect in 1999, dealing largely with administrative and procedural rules. More recent amendments to Part I clarified certain administrative and procedural issues raised by over 10 years of practice of the application of Part I of the Tax Code (in particular, regarding tax audit procedures, procedural guarantees for taxpayers, operations with taxpayer bank accounts and bank liability). The provisions of Part II of the Tax Code regarding excise taxes, VAT, individual income tax, and the unified social tax (currently replaced by social security contributions) came into force in 2001, followed by the profits tax and mineral extraction tax provisions of the Tax Code in 2002. In 2003 further amendments introduced a simplified system of taxation, a single tax on imputed income, a new Chapter on transportation tax, and established a special tax regime for production sharing agreements in Russia. A Chapter on corporate property tax came into effect as of 1 January 2004. In 2005 the water tax, land tax, and state duty Chapters came into effect. On 1 January 2013 a Chapter on a patent system of taxation (for small businesses) and on 1 January 2015 a Chapter on trade levy took effect. -

Foreign Recipients of U.S. Income, and Tax Withheld, 1985

Foreign Recipients of U.S. Income, and Tax Withheld, 1985 By Margaret P. Lewis* Total income paid to foreign persons (including individ- foreign recipients did not file a U.S. income tax return be- uals, corporations and other organizations) from U.S. cause their tax liability had thus been satisfied at its source. sources increased 2 percent in 1985 to $17.5 billion; at the The responsibility for withholding this tax belonged to the same time, U.S. tax withheld on this income fell to $940 payer or a representative of the payer (usually a financial insti- million, a 3 percent decrease [1]. U.S. source income in- tution). Income connected with a foreign recipient's U.S. trade cluded such items as interest and dividend payments, rents or business was exempt from such withholding. The United and royalties, but not income "effectively connected" with a States taxed this income separately, the same as though it U.S. trade or business, or interest paid on bank deposits. were received by a U.S. citizen or corporation. Amounts of The total income figure included $748 million in social secu- such "effectively connected" income are not included in the rity and railroad retirement payments which became sub- statistics for U.S. source income presented here. ject to tax withholding beginning in 1984 and were included for the first time in the statistics for 1985. Nearly $80 million U.S. source income was taxed at a flat rate (generally 30 in tax was withheld on these payments in 1985. The de- percent) rather than being subject to graduated tax rates as crease in total tax withheld resulted partially from the re- was the income of U.S.