Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

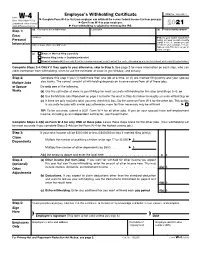

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Publication 509, Tax Calendars

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P509/2021/A/XML/Cycle13/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 13 10:55 - 31-Dec-2020 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 509 Cat. No. 15013X Contents Introduction .................. 2 Department of the Tax Calendars Background Information for Using Treasury the Tax Calendars ........... 2 Internal Revenue General Tax Calendar ............ 3 Service First Quarter ............... 3 For use in Second Quarter ............. 4 2021 Third Quarter ............... 4 Fourth Quarter .............. 5 Employer's Tax Calendar .......... 5 First Quarter ............... 6 Second Quarter ............. 7 Third Quarter ............... 7 Fourth Quarter .............. 8 Excise Tax Calendar ............. 8 First Quarter ............... 8 Second Quarter ............. 9 Third Quarter ............... 9 Fourth Quarter ............. 10 How To Get Tax Help ........... 12 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 509, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub509. What’s New Payment of deferred employer share of so- cial security tax from 2020. If the employer deferred paying the employer share of social security tax in 2020, pay 50% of the employer share of social security tax by January 3, 2022 and the remainder by January 3, 2023. Any payments or deposits you make before January 3, 2022, are first applied against the first 50% of the deferred employer share of social security tax, and then applied against the remainder of your deferred payments. Payment of deferred employee share of so- cial security tax from 2020. -

University of Allahabad

UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD INFORMATION AND GUIDELINES FOR COMBINED RESEARCH ENTRANCE TEST (CRET) – 2018 Academic Session: 2018 - 19 SCHEDULE:The schedule of CRET-2018 has been as under: Form available Online at auadmissions.comOR Admission-2018 link of www.allduniv.ac.in Commencement of registration and submission ONLINE 22ndApril, 2018 Last date of Registration, Fee Deposition and 30th May, 2018 Form Submission ONLINE 16th May, 2018 Downloading of Admit Cards Online only 7th June, 2018 Date of Entrance Test 13th June, 2018 The University of Allahabad shall conduct COMBINED RESEARCH ENTRANCE TEST- 2018 (CRET-2018) at Allahabad for admission to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) (hereinafter referred to as D.Phil. Programme) of the University of Allahabad for the session 2018-19 in the subjects specified in SECTION 2 of this Bulletin. As laid down in the Ordinance LVI of the First Ordinance of Allahabad University (made under Section 29 of the University of Allahabad Act, 2005) candidates for admission to the degree of D. Phil. Programme must hold a Master’s degree (or a degree recognized by the University as equivalent thereto) in a relevant subject from the University, or any other University or an Institution recognized by it, and must fulfill other prescribed conditions of eligibility. Regular teachers of the University of Allahabad and of any institution maintained by it or admitted to its privileges and international Students are exempted from appearing at CRET for admission to D. Phil. Programme. All other candidates for admission to the D. Phil. Programme in the concerned subjects are required to appear at CRET-2018 after applying and register their candidature through the ONLINE APPLICATION AND REGISTRATION PROCESS at the website auadmissions.com OR Admission-2018 link of www.allduniv.ac.inand remitting the admissible Test Fee in the prescribed manner. -

Publication 517, Social Security

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P517/2020/A/XML/Cycle03/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 18 11:42 - 2-Mar-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 517 Cat. No. 15021X Contents Future Developments ............ 1 Department of the Social Security What's New .................. 1 Treasury Internal Reminders ................... 2 Revenue and Other Service Introduction .................. 2 Information for Social Security Coverage .......... 3 Members of the Ministerial Services ............. 4 Exemption From Self-Employment Clergy and (SE) Tax ................. 6 Self-Employment Tax: Figuring Net Religious Earnings ................. 7 Income Tax: Income and Expenses .... 9 Workers Filing Your Return ............. 11 Retirement Savings Arrangements ... 11 For use in preparing Earned Income Credit (EIC) ....... 12 Worksheets ................. 14 2020 Returns How To Get Tax Help ........... 15 Index ..................... 18 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 517, such as legislation enacted after this publication was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub517. What's New Tax relief legislation. Recent legislation pro- vided certain tax-related benefits, including the election to use your 2019 earned income to fig- ure your 2020 earned income credit. See Elec- tion to use prior-year earned income for more information. Credits for self-employed individuals. New refundable credits are available to certain self-employed individuals impacted by the coro- navirus. See the Instructions for Form 7202 for more information. Deferral of self-employment tax payments under the CARES Act. The CARES Act al- lows certain self-employed individuals who were affected by the coronavirus and file Schedule SE (Form 1040), to defer a portion of their 2020 self-employment tax payments until 2021 and 2022. -

Paolo Silvestri Anthropology of Freedom and Tax Justice: Between Exchange and Gift

Paolo Silvestri Anthropology of Freedom and Tax Justice: between Exchange and Gift. Thoughts for an interdisciplinary research agenda1 1. Introduction The way in which fiscal institutions and fiscal policies are conceived and imple- mented raises problems at the intersection of so many ethical, institutional, legal, political and philosophical issues, both practical and theoretical, that a unified framework of all these rather fragmented issues seems to be quite impossible. Let us consider just a few of these issues. The performance of fiscal institutions is crucial for its effects on equality, inclusiveness and social mobility. Tax issues, or, rather, tax injustices are at the core, if not the origin of modern democratic and legal-political (and not only economic) institutions. The arrangement of fiscal institutions touches salient political-social issues, many of them at the heart of a sound and democratic good governance both at local and global level: transparency, accountability, efficacy, legitimacy, and trust. Last but not least, taxation is ambivalently connected to citi- zens’ trust/distrust relationships: among themselves as well as toward political, legal, and administrative institutions, since taxation is often perceived as the most immedi- ate presence (for better or for worse) of such institutions in their lives. 1 This little essay is dedicated to a great man, a man who one day gave me a great gift, rekindling my hopes for the future. At the time when I received that gift, I immediately felt an immense sense of gratitude, and an immediate boost to find ways to be able to pay my debts and honour, at my very best, the credit and trust I was given. -

Investors' Reaction to a Reform of Corporate Income Taxation

Investors' Reaction to a Reform of Corporate Income Taxation Dennis Voeller z (University of Mannheim) Jens M¨uller z (University of Graz) Draft: November 2011 Abstract: This paper investigates the stock market response to the corporate tax reform in Germany of 2008. The reform included a decrease in the statutary corporate income tax rate from 25% to 15% and a considerable reduction of interest taxation at the shareholder level. As a result, it provided for a higher tax benefit of debt. As it comprises changes in corporate taxation as well as the introduction of a final withholding tax on capital income, the German tax reform act of 2008 allows for a joint consideration of investors' reactions on both changes in corporate and personal income taxes. Analyzing company returns around fifteen events in 2006 and 2007 which mark important steps in the legislatory process preceding the passage of the reform, the study provides evidence on whether investors expect a reduction in their respective tax burden. Especially, it considers differences in investors' reactions depending on the financial structure of a company. While no significant average market reactions can be observed, the results suggest positive price reactions of highly levered companies. Keywords: Tax Reform, Corporate Income Tax, Stock Market Reaction JEL Classification: G30, G32, H25, H32 z University of Mannheim, Schloss Ostfl¨ugel,D-68161 Mannheim, Germany, [email protected]. z University of Graz, Universit¨atsstraße15, A-8010 Graz, Austria, [email protected]. 1 Introduction Previous literature provides evidence that companies adjust their capital structure as a response to changes in the tax treatment of different sources of finance. -

Cross-Border Planning for Canadian Registered Retirement Plans

CROSS-BORDER PLANNING FOR CANADIAN REGISTERED RETIREMENT PLANS Elise M. Pulver, David J. Byun, Ryan M. Murphy and Amy P. Walters* Each year, many Canadians choose to move to the United States for various reasons, including, inter alia, employment opportunities, retirement destinations, and lower tax rates. Whatever the reason may be, there are several important planning questions to consider before making the move. The purpose of this paper is to address one such key consideration: the cross-border tax implications in respect of registered retirement plans. This paper is divided into three parts. The first part analyzes the Canadian taxation of distributions from Canadian registered retirement plans, upon the plan owner's death, to a beneficiary who is a non-resident of Canada. The second part discusses how a Canadian who moves south of the border and becomes a U.S. citizen or resident alien would be taxed by the U.S. tax system vis-aÁ-vis the distributions from his or her Canadian registered retirement plans. Conversely, the final part of the paper provides an overview of the U.S. taxation of a U.S. non-resident alien with respect to distributions from his or her U.S. retirement plans. I. CANADIAN TAXATION OF CANADIAN REGISTERED RETIREMENT PLANS UPON DEATH This part of the paper looks at the Canadian taxation of the payment from a registered retirement plan (namely, a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (ªRRSPº) and Registered Retirement Income Fund (ªRRIFº)) upon the plan owner's death, to a beneficiary who is a non-resident of Canada. In particular, it addresses whether a non-resident beneficiary of such registered plan would be subject to any withholding tax on such payment * Elise M. -

Publication 523 Reminders

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 10 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P523/2020/A/XML/Cycle04/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 22 12:06 - 1-Mar-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Department of the Treasury Contents Internal Revenue Service Future Developments ....................... 1 Publication 523 Reminders ............................... 1 Cat. No. 15044W Introduction .............................. 2 Does Your Home Sale Qualify for the Exclusion of Gain? .............................. 2 Selling Eligibility Test ........................... 3 Does Your Home Qualify for a Partial Your Home Exclusion of Gain? ...................... 6 Figuring Gain or Loss ....................... 7 For use in preparing Basis Adjustments—Details and Exceptions ..... 8 Business or Rental Use of Home ............ 11 Returns 2020 How Much Is Taxable? ..................... 14 Recapturing Depreciation ................. 15 Reporting Your Home Sale .................. 15 Reporting Gain or Loss on Your Home Sale .... 16 Reporting Deductions Related to Your Home Sale ............................... 17 Reporting Other Income Related to Your Home Sale .......................... 17 Paying Back Credits and Subsidies .......... 18 How To Get Tax Help ...................... 18 Index .................................. 22 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 523, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub523. Reminders Photographs of missing children. The IRS is a proud partner with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children® (NCMEC). Photographs of missing children se- lected by the Center may appear in this publication on pa- ges that would otherwise be blank. You can help bring these children home by looking at the photographs and calling 800-THE-LOST (800-843-5678) if you recognize a child. -

Financing COVID-19 Costs in Germany: Is a Wealth Tax a Sensible Approach?

International Background Paper Wealth Tax Commission Financing COVID-19 costs in Germany: is a wealth tax a sensible approach? Author Ruben Rehr FINANCING COVID-19 COSTS IN GERMANY – IS A WEALTH TAX A SENSIBLE APPROACH? Ruben Rehr, Bucerius Law School, Germany Wealth Tax Commission Background Paper no. 131 Published by the Wealth Tax Commission www.ukwealth.tax Acknowledgements The Wealth Tax Commission acknowledges funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the CAGE at Warwick (ES/L011719/1) and a COVID-19 Rapid Response Grant (ES/V012657/1), and a grant from Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity's COVID-19 Rapid Response Fund. 2 1. Introduction In these trying times, the German economy suffers from lockdowns and restrictions necessary due to the COVID-19 crisis. Much of that bill is footed by the taxpayer through a stimulus package worth 170 billion euros, enacted by the federal Government to combat recession.1 It is likely that such government spending will at some point in the future require higher tax revenue. The Social Democrats2 (SPD) and the Socialists3 (Die Linke) have used this opportunity to revive the idea of taxing wealth. Reintroducing a wealth tax is an election campaign evergreen. It might be because the wealth tax is automatically understood as only taxing the rich.4 Estimates assume that only 0.17%5 to 0.2%6 of taxpayers would be subjected to such a wealth tax and it appears that taxes paid by others enjoy popularity amongst the electorate. Currently the Social Democrats,7 the Greens,8 and the Socialists9 support its reintroduction. -

Pub 515, Withholding of Tax on Nonresident Aliens and Foreign

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … tions/P515/2021/A/XML/Cycle05/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 56 16:15 - 3-Feb-2021 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 515 Cat. No. 15019L Contents What's New .................. 1 Department of the Withholding Reminders ................... 2 Treasury Internal Introduction .................. 2 Revenue of Tax on Service Withholding of Tax .............. 3 Nonresident Persons Subject to Chapter 3 or Chapter 4 Withholding ......... 5 Aliens and Documentation ............... 10 Foreign Entities Income Subject to Withholding ..... 23 Withholding on Specific Income ..... 26 Foreign Governments and Certain Other Foreign Organizations .... 39 For use in 2021 U.S. or Foreign TINs ............ 40 Depositing Withheld Taxes ........ 41 Returns Required .............. 42 Partnership Withholding on Effectively Connected Income ... 43 Section 1446(f) Withholding ....... 46 U.S. Real Property Interest ........ 48 Definitions .................. 51 Tax Treaties ................. 52 How To Get Tax Help ........... 52 Index ..................... 55 Future Developments For the latest information about developments related to Pub. 515, such as legislation enacted after it was published, go to IRS.gov/Pub515. What's New New requirement to fax requests for exten- sion to furnish statements to recipients. Requests for an extension of time to furnish cer- tain statements to recipients, including Form 1042-S, should now be faxed to the IRS. For more information see Extension to furnish state- ments to recipients under Extensions of Time To File, later. COVID-19 relief for Form 8233 filers. The IRS has provided relief from withholding on compensation for certain dependent personal services, for individuals who were unable to leave the United States due to the global health Get forms and other information faster and easier at: emergency caused by COVID-19. -

Petroleum Profit Tax and Economic Growth in Nigeria

International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research Volume 1, Issue 9 2012 – ISSN (2226-8235) PETROLEUM PROFIT TAX AND ECONOMIC GROWTH IN NIGERIA BY 1) APPAH EBIMOBOWEI DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING, BAYELSA STATE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, OKPOAMA, BRASS-ISLAND, YENAGOA, NIGERIA & 2) EBIRINGA, O.T. DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGY, FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, OWERRI, NIGERIA. ABSTRACT This study investigates the impact of petroleum profit tax on the economic growth of Nigeria. To achieve the objective of this paper, relevant secondary data were collected from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) from 1970 to 2010. The secondary data collected from the relevant government agencies in Nigeria were analysed with relevant econometric tests of Breusch -Godfrey Serial Correlation LM, White Heteroskedasticity, Ramsey RESET, Jarque Bera, Johansen Co-integration, and Granger Causality. The results show that there exists a long run equilibrium relationship between economic growth and petroleum profit tax. It was also found that petroleum profit tax does granger cause gross domestic product of Nigeria. On the basis of the empirical analysis, the paper concludes that petroleum profit tax is one of the most important components direct taxes in Nigeria that affects the economic growth of the country and therefore should be properly managed to reduce the level of evasion by petroleum exploration companies in Nigeria. The paper recommends among others that companies involved in petroleum operations should be properly supervised by the relevant tax authority (FIRS) to reduce the level of tax evasion; government should show more accountabi lity in the management of tax revenue and finally, the level of corruption in Nigeria and that of government officials should be drastically reduced to win the confidence of tax payers for voluntary tax compliance. -

2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns

2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide For 2020 Returns A Supplement to the 2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns For the 2020 tax year, the Church Pension Group (CPG) is providing the 2021 Clergy Tax Return Preparation Guide for 2020 Returns and the 2021 Federal Reporting Requirements for Episcopal Churches, Schools, and Institutions (Federal Reporting Requirements Guide) as references to help clergy, treasurers and bookkeepers, and tax preparers in better understanding clergy taxes. These guides are available on CPG’s website at cpg.org. This supplement complements the guides. The supplement is presented in two sections. First, a section on tax highlights addresses recent tax changes. Second, a question-and-answer format addresses key tax issues, and information provided in the guides and how it specifically applies to clergy of The Episcopal Church. Note: If you have questions about clergy federal income taxes that are not covered here, please call CPG’s Tax Hotline: Nancy Fritschner, CPA (877) 305-1414 Mary Ann Hanson, CPA (877) 305-1415 Dolly Rios,* CPA (833) 363-5751 *Fluent in English and Spanish Please note that the service these individuals will provide is of an informational nature. It should not be viewed as tax, legal, financial, or other advice. You must contact your tax advisor for assistance in preparing your tax returns or for other tax advice. Tax Highlights The SECURE (Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement) Act of 2019 is now law. Most provisions in the law became effective January 1, 2020. Listed below are some of the most important changes that could have a significant impact on you.