Who Wrote the Nun's Life of Edward? 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Edward the Confessor Feast: October 13

St. Edward the Confessor Feast: October 13 Facts Feast Day: October 13 Edward the Confessor was the son of King Ethelred III and his Norman wife, Emma, daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy. He was born at Islip, England, and sent to Normandy with his mother in the year 1013 when the Danes under Sweyn and his son Canute invaded England. Canute remained in England and the year after Ethelred's death in 1016, married Emma, who had returned to England, and became King of England. Edward remained in Normandy, was brought up a Norman, and in 1042, on the death of his half-brother, Hardicanute, son of Canute and Emma, and largely through the support of the powerful Earl Godwin, he was acclaimed king of England. In 1044, he married Godwin's daughter Edith. His reign was a peaceful one characterized by his good rule and remission of odious taxes, but also by the struggle, partly caused by his natural inclination to favor the Normans, between Godwin and his Saxon supporters and the Norman barons, including Robert of Jumieges, whom Edward had brought with him when he returned to England and whom he named Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051. In the same year, Edward banished Godwin, who took refuge in Flanders but returned the following year with a fleet ready to lead a rebellion. Armed revolt was avoided when the two men met and settled their differences; among them was the Archbishop of Canterbury, which was resolved when Edward replaced Robert with Stigand, and Robert returned to Normandy. -

Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Archaeological Evaluation by Graham Hull Site Code: ABR14 ABR15/191 (TQ 4385 8400) Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham An Archaeological Evaluation for Wolford Ltd by Graham Hull Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code: ABR14 March 2016 Summary Site name: Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Grid reference: TQ 4385 8400 (site centre) Site activity: Archaeological Evaluation Date and duration of project: 18th - 25th February 2016 Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Graham Hull Site code: ABR14 Area of site: 2.07ha Summary of results: Five evaluation trenches were excavated. Three located archaeological features, deposits and finds that date from the Roman, Saxon, medieval and post-medieval periods. A possible Saxon ditch was found. A deposit model based on borehole logs, previous archaeological excavations, evaluation trenching and cartographic study identified a geological discontinuity with alluvium to the west and north of the site and glacial tills to the east and south-east. Finds include Roman and medieval brick and tile, Saxon, medieval and post-medieval pottery, animal bone and worked timber. The evaluation trenching has provided further evidence for Saxon and medieval activity associated with Barking Abbey. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited at The Museum of London in due course, with accession code ABR14. -

Church of Saint Edward the Confessor

Mike Greene 740-345-3510 Village Tim Hughes Realtor 51 North Third Tower • Newark Flower Basket 1090 River Road VILLAGE FLOWER Granville Business Proudly serving the area for over 37 years! BASKET & GARDENS Church of Saint Edward Technologies, Inc. GRANVILLE, OHIO 587-3439 328-9051 COPIERS • PRINTERS • FAX 1290 HEBRON RD., Kelly Parker – Professional Full Home of Service REALTOR® HEATH, OH Ye Olde 238 E. Broadway, Jeep Mill (1 mile South of Indian Mound Mall) Since 1914 David Hughes, OCNT Granville, OH the Confessor 11324 Mt. Vernon Rd., Utica FAMILY OWNED MEMBERS 740-892-3921 740-344-5493 Cell 740-334-9777 OVER 37 YEARS 522-3153 OF PARISH www.velveticecream.com “We Share Your Passion for Garden Excellence” KellyParkerHome.com Serving Granville & A Place To Call Om Newark for Leigh Brennan, RYT • 740-404-9190 • aplacetocallom.com Grand pastor: DeaCon: over 29 years. Mon., 6:30pm – Power Flow with Weights; Monuments SGR AUL NKE EV R OHN ARBOUR 345-2086 Tues., 9:30am – Flow Yoga; Wed., 7:45pm – Flow Yoga; 1600 East Main St. M . P P. E R . M . J B Residential & Commercial Newark, Ohio 43055 Visa & MasterCard accepted Fri., 9:00am – Flow Yoga; Sat., 11:45am – Power Flow Yoga; www.bigorefuse.com Sun., 7:30pm – Gentle Yoga 345-8772 1190 E. Main Street, Newark, OH 43055 740-349-8686 assisting Clergy AUTOMOTIVE PAINTLESS DENT REMOVAL FR. RONNIE BOCCALI, P.I.M.E. Downey’s Carpet Care • 22 Years Experience • Hail Damage • Body Line Dents FR. JAY HARRINGTON, O.P. of Granville • Crease Dents • Door Dings 587-4258 Bag & Bulk Mulch – Plants – Stone – Topsoil ERIC CLAEYS 740-404-5508 • Motorcycles 2135 West Main, Newark • www.hopetimber.com 462 S. -

View of the English Church, Viewing It As Backward at Best

© 2013 TAMARA S. RAND ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “AND IF MEN MIGHT ALSO IMITATE HER VIRTUES” AN EXAMINATION OF GOSCELIN OF SAINT-BERTIN’S HAGIOGRAPHIES OF THE FEMALE SAINTS OF ELY AND THEIR ROLE IN THE CREATION OF HISTORIC MEMORY A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Tamara S. Rand May, 2013 “AND IF MEN MIGHT ALSO IMITATE HER VIRTUES” AN EXAMINATION OF GOSCELIN OF SAINT-BERTIN’S HAGIOGRAPHIES OF THE FEMALE SAINTS OF ELY AND THEIR ROLE IN THE CREATION OF HISTORIC MEMORY Tamara S. Rand Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Constance Bouchard Dr. Martin Wainwright ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Michael Graham Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Michael J. Levin Dr. George R. Newkome ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Isolde Thyret ______________________________ Committee Member Dr. Hillary Nunn ______________________________ Committee Member Dr. Alan Ambrisco ii ABSTRACT This dissertation addresses the ways hagiographies were used to engage in memory creation and political criticism by examining them as postcolonial discourse. In it, I study the hagiographies written about the royal female saints of Ely by the Flemish monk Goscelin of Saint-Bertin in the late eleventh century as a form of postcolonial literature and memory creation. Goscelin was a renowned writer of Anglo-Saxon saints’ lives. Through his hagiographies he not only created images of England’s Christian past that emphasized its pious, sophisticated rulers and close ties to the papacy, he engaged in political commentary and criticism. -

Heritage-Champion-JD

Chelmsford Diocesan Board of Finance Job Description Job Title: Heritage Champion (12 month fixed term contract for full time hours or up to 16 month fixed term contract for part time hours) Reporting The post holder will report to the Project Team, via the Borough arrangements: Archivist (London Borough of Barking and Dagenham) Salary: £23,000 to £25,600p.a. pro rata, subject to skills, experience and qualifications Working Hours: Full time and part time working will be considered A full time contract will be for 35 hours per week Part time hours will be considered, with the option for a longer fixed term contract (e.g. for up to 16 months) Purpose Statement The Heritage Champion will enable and inspire outreach and community engagement activities, so that many people (especially local residents) will be able to encounter and discover the long and important history of Barking Abbey. Reporting Structure The post holder will report to the Project Team, via the Borough Archivist (London Borough of Barking and Dagenham). Nature and Scope A thousand years ago Barking Abbey was one of the great places of England – and had already been so for nearly 400 years - and would continue to be so for a further 400. There is a wealth of archaeology and history here to celebrate. We are a partnership of four organisations: - • The London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (owner of most of the site, including the Abbey ruins, a scheduled Ancient Monument), • St Margaret’s church (a remaining original building and an active church still), • the Diocese of Chelmsford (who the post holder will be employed by), and • the Museum of London Archaeology team. -

St. Edward the Confessor

St. Edward the Confessor 205 Jackson Avenue, Syosset, New York 11791 Growing in Faith, Love, and Christ “I will place my law within them and write it upon their hearts; I will be their God, and they shall be my people. :” Jeremiah 31:33 Fifth Sunday of Lent March 21st, 2021 THE PASTORAL TEAM Rev. Michael T. Maffeo, Pastor Rev. Hyacinth Jemigbola, Associate Pastor Rev. Celestine Nwosu, Associate Pastor Msgr. Donald E. Beckmann, Sunday Priest Deacon James F. Murphy Deacon Barry P. Croce Administration Deacon Thomas Wm. Connolly, Director Pastoral Center Offices Office StaffRCIA (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) Mr. Miguel DeLeon, Finance DirectorMrs. Maryann Waite Sister Sheila Browne, RSM, Director Mrs. Luisa Ondocin St. Edward the Confessor School Parish Social Ministry Office Staff Mr. Vincent Albrecht, Principal Mrs. Donna Zaino, Coordinator Mrs. Maryann Waite Ms. Taylor Moran Mrs. Luisa Ondocin Music Ministry Youth Ministry Religious Education Mr. Jeffrey Fox Ms. Michelle Sena - Vision Mrs. Rosemary Pettei, Director Mrs. Marilyn Fox Ms. Mary Calabrese, Director of Confirmation Mrs. Ann Braun, Secretary Quick Guide to St. Edward’s Parish Not registered? Please stop by our Rectory during office hours to be included in our parish family! Rectory Hours Telephone Numbers The rectory will be open during the following times: Mondays - Thursdays: 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM Rectory……………………………………..921-8030 ext. 150 Fridays: 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM Rectory Fax……………………………....………….921-4549 Closed for Lunch M-F: 1:00 PM to 2:00 PM St. Edward Confessor School………….…………....921-7767 Saturdays - Sundays: 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM Religious Education Office………………………....921-8543 Outside of these hours, please call: 516-921-8030 RCIA……………………………...……….921-8030 ext. -

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.Net

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.net Edward the Martyr (Old English: Eadweard; c. 962 – 18 March 978) was King of England from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar the Peaceful but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his much younger half-brother Æthelred the Unready, recognized as a legitimate son of Edgar. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan and Oswald of Worcester. The great nobles of the kingdom, ealdormen Ælfhere and Æthelwine, quarrelled, and civil war almost broke out. In the so-called anti-monastic reaction, the nobles took advantage of Edward's weakness to dispossess the Benedictine reformed monasteries of lands and other properties that King Edgar had granted to them. Edward's short reign was brought to an end by his murder at Corfe Castle in 978 in circumstances that are not altogether clear. His body was reburied with great ceremony at Shaftesbury Abbey early in 979. In 1001 Edward's remains were moved to a more prominent place in the abbey, probably with the blessing of his half-brother King Æthelred. Edward was already reckoned a saint by this time. A number of lives of Edward were written in the centuries following his death in which he was portrayed as a martyr, generally seen as a victim of the Queen Dowager Ælfthryth, mother of Æthelred. -

Ss. Peter & Paul

3rd Sunday After Pentecost Tone 2 June 17, 2018 SS. PETER & PAUL Lorain, OH | www.OrthodoxLorain.org | (440) 277-6266 Rev. Joseph McCartney, Rector Cell (440) 668 - 2209 ~ Email: [email protected] ~ Home (440) 654-2831 Gospel Reading ~ Matthew 6:22-33 Epistle Reading ~ Romans 5:1-10 All Saints of Britain and Ireland This Week at a Glance Gospel Meditation Wed, June 20th In today’s Gospel, Jesus says that the light of the body is the eye. If 6:00 pm - Akathist to Ss Peter the eye is light, so the body will be light. But if the eye is dark, so the body & Paul will be dark. By 'eye' is meant the soul, for the eye is the window of the soul. In these words Our Lord says that we are not to blame our bodies for our Sat, June 23rd sins. Our bodies are the servants of our souls. If our souls are corrupted, then 6:00 pm - Great Vespers so also will be our bodies. On the other hand, if our souls are clean, then our bodies will also be clean. It is not our bodies which control our lives, or even Sun, June 24th our minds, but our souls. And it is our souls that we are called on to cleanse, 9:00 pm - 3rd & 6th Hours cultivate and refine first of all. It is the spiritual which has primacy in our 9:30 am - Divine Liturgy lives. Once our souls are clean, then our minds and our bodies will also be cleaned. Neither can we serve two Masters, the master of the material world Parish Council and the master of the spiritual world. -

Barking and Dagenham from High Road to Longridge Road

i.i—^Ufcflikmr R|LONDON^THE LQIVDON BOROUGHS NDTHE DAGENHAM v^-m NEWHAM IB, HAVERING LB 'Ii "^1 « HAVERING DAGENHAM •*'j&* J$! «V^v • REPORT NO. 660 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 660 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr K F J Ennals CB MEMBERS Mr G R Prentice Mrs H R V Sarkany Mr C W Smith Professor K Young -4 ,« CONTENTS Paragraphs Introduction 1-5 Our approach to the review of Greater London 6-10 The initial submissions made to us 11 Our draft and further draft proposals letters and the responses to them 12-18 Barking & Dagenham/Redbridge/Havering boundaries: the salient between Chadwell Heath and Marks Gate 19-20 The salient and Marks Gate 21-37 Chadwell Heath and East Road area 38-44 Crow Lane 45-52 Barking & Dagenham/Redbridge boundary St Chad's Park 53-55 The Becontree Estate 56-72 South Park Drive 73-74 Victoria Road 75-79 Barking & Dagenham/Newham boundary River Roding and the A406 80-93 Electoral Consequentials 94 Conclusion 95 Publication 96-97 THE RT HON MICHAEL HOWARD QC MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1972 REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON THE LONDON BOROUGH OF BARKING & DAGENHAM AND ITS BOUNDARIES WITH THE LODON BOROUGHS OF REDBRIDGE, NEWHAM AND HAVERING (AT MARKS GATE AND CROW LANE ONLY) COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 1. This is our final report on the boundaries between the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham and its neighbouring local authorities. -

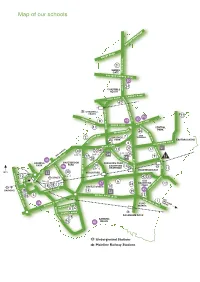

Map of Our Schools

Map of our schools 21 50 34 29 49a 22 43 8 49 41 26 2 7 25 (SITE 1) 4 23 37 17 51 30 20 40 (SITE 2) (SITE 2) (SITE 1) 54 25 27 54a 9 55 44 28 44a 20 16 (SITE 2) 11 52 30 15 (SITE 1) 42 33 (SITE 2) 6 3 47 24 12 18 18 10 (SITE 1) 45 38 14 53 39 36 5 13 1 46 31 32 19 35 48 Schools’ details Map Map number School name number School name Primary schools (ages 4 to 11) Faith Primary schools (ages 4 to 11) 1 Beam Primary, Oval Road North, Dagenham, RM10 9ED F35 George Carey CofE Primary, Minter Road, Barking IG11 0FJ 2 Becontree Primary, Stevens Road, Dagenham, RM8 2QR F36 St Joseph’s Catholic Primary, The Broadway, Barking, IG11 7AR 3 Eastbury Primary, Dawson Avenue, Barking IG11 9QQ F37 St Joseph’s Catholic Primary, Connor Road, Dagenham, RM9 5UL 4 Five Elms Primary, Wood Lane, Dagenham, RM9 5TB F38 St Margarets C of E Primary, North Street, Barking, IG11 8AS 5 Gascoigne Primary, Gascoigne Road, Barking, IG11 7DR F39 St Peter’s Catholic Primary, Goresbrook Road, Dagenham, RM9 6UU 6 Godwin Primary, Finneymore Road, Dagenham, RM9 6JH F40 St Teresa Catholic Primary, Bowes Road, Dagenham, RM8 2XJ 7 Grafton Primary, Grafton Road, Dagenham, RM8 3EX F41 St Vincent’s Catholic Primary, Burnside Road, Dagenham, RM8 2JN 8 Henry Green Primary, Green Lane, Dagenham, RM8 1UR 9 Hunters Hall Primary, Alibon Road, Dagenham, RM10 8DE Map number School name 10 James Cambell Primary, Langley Crescent, Dagenham, RM9 6TD Faith Junior schools (ages 7 to 11) 11 John Perry Primary, Charles Road, Dagenham, RM10 8UR F42 William Ford C of E Junior, Ford Road, Dagenham, -

St. Edward the Confessor

St. Edward the Confessor 205 Jackson Avenue, Syosset, New York 11791 Growing in Faith, Love, and Christ “If I but touch his clothes, I shall be cured.” Mark 5:28 Thirteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time June 27th, 2021 THE PASTORAL TEAM Rev. Michael T. Maffeo, Pastor Rev. Hyacinth Jemigbola, Associate Pastor Rev. Celestine Nwosu, Associate Pastor Rev. Msgr. Donald McE. Beckmann, Sunday Priest Deacon James F. Murphy Deacon Barry P. Croce Administration Deacon Thomas Wm. Connolly, Director Pastoral Center Offices Office StaffRCIA (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults) Mr. Miguel DeLeon, Finance DirectorMrs. Maryann Waite Sister Sheila Browne, RSM, Director Mrs. Luisa Ondocin St. Edward the Confessor School Parish Social Ministry Office Staff Mr. Vincent Albrecht, Principal Mrs. Donna Zaino, Coordinator Mrs. Maryann Waite Ms. Taylor Moran Mrs. Luisa Ondocin Music Ministry Youth Ministry Religious Education Mr. Jeffrey Fox Ms. Michelle Sena - Vision Mrs. Rosemary Pettei, Director Mrs. Marilyn Fox Ms. Mary Calabrese, Director of Confirmation Mrs. Cecilia Hayden Mrs. Ann Braun, Secretary Quick Guide to St. Edward’s Parish Not registered? Please stop by our Rectory during office hours to be included in our parish family! Rectory Hours Telephone Numbers The rectory will be open during the following times: Mondays - Thursdays: 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM Rectory……………………………………..921-8030 ext. 150 Fridays: 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM Rectory Fax……………………………....………….921-4549 Closed for Lunch M-F: 1:00 PM to 2:00 PM St. Edward Confessor School………….…………....921-7767 Saturdays - Sundays: 9:00 AM to 1:00 PM Religious Education Office………………………....921-8543 Outside of these hours, please call: 516-921-8030 RCIA……………………………...……….921-8030 ext. -

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti Eethelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti EEthelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi Nicola Jane Robertson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, Centre for Medieval Studies, September 2003 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Mary Swan and Professor Ian Wood for their guidance and support throughout the course of this project. Professor Wood's good-natured advice and perceptive comments have helped guide me over the past four years. Dr Swan's counsel and encouragement above and beyond the call of duty have kept me going, especially in these last, most difficult stages. I would also like to thank Dr William Flynn, for all his help with my Latin and useful commentary, even though he was not officially obliged to offer it. My advising tutor Professor Joyce Hill also played an important part in the completion of this work. I should extend my gratitude to Alison Martin, for a constant supply of stationery and kind words. I am also grateful for the assistance of the staff of the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. I would also like to thank all the students of the Centre for Medieval Studies, past and present, who have always offered a friendly and receptive environment for the exchange of ideas and assorted cakes.