London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Rivers Action Plan

The london rivers action plan A tool to help restore rivers for people and nature January 2009 www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php acknowledgements 1 Steering Group Joanna Heisse, Environment Agency Jan Hewlett, Greater London Authority Liane Jarman,WWF-UK Renata Kowalik, London Wildlife Trust Jenny Mant,The River Restoration Centre Peter Massini, Natural England Robert Oates,Thames Rivers Restoration Trust Kevin Reid, Greater London Authority Sarah Scott, Environment Agency Dave Webb, Environment Agency Support We would also like to thank the following for their support and contributions to the programme: • The Underwood Trust for their support to the Thames Rivers Restoration Trust • Valerie Selby (Wandsworth Borough Council) • Ian Tomes (Environment Agency) • HSBC's support of the WWF Thames programme through the global HSBC Climate Partnership • Thames21 • Rob and Rhoda Burns/Drawing Attention for design and graphics work Photo acknowledgements We are very grateful for the use of photographs throughout this document which are annotated as follows: 1 Environment Agency 2 The River Restoration Centre 3 Andy Pepper (ATPEC Ltd) HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This booklet is to be used in conjunction with an interactive website administered by the The River Restoration Centre (www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php).Whilst it provides an overview of the aspirations of a range of organisations including those mentioned above, the main value of this document is to use it as a tool to find out about river restoration opportunities so that they can be flagged up early in the planning process.The website provides a forum for keeping such information up to date. -

A Unique Experience with Albion Journeys

2020 Departures 2020 Departures A unique experience with Albion Journeys The Tudors & Stuarts in London Fenton House 4 to 11 May, 2020 - 8 Day Itinerary Sutton House $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy Eastbury Manor House The Charterhouse St Paul’s Cathedral London’s skyline today is characterised by modern high-rise Covent Garden Tower of London Banqueting House Westminster Abbey The Globe Theatre towers, but look hard and you can still see traces of its early Chelsea Physic Garden Syon Park history. The Tudor and Stuart monarchs collectively ruled Britain for over 200 years and this time was highly influential Ham House on the city’s architecture. We discover Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of the city’s churches after the Great Fire of London along with visiting magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral. We also travel to the capital’s outskirts to find impressive Tudor houses waiting to be rediscovered. Kent Castles & Coasts 5 to 13 May, 2020 - 9 Day Itinerary $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy The romantic county of Kent offers a multitude of historic Windsor Castle LONDON Leeds Castle Margate treasures, from enchanting castles and stately homes to Down House imaginative gardens and delightful coastal towns. On this Chartwell Sandwich captivating break we learn about Kent’s role in shaping Hever Castle Canterbury Ightham Mote Godinton House English history, and discover some of its famous residents Sissinghurst Castle Garden such as Ann Boleyn, Charles Dickens and Winston Churchill. In Bodiam Castle a county famed for its castles, we also explore historic Hever and impressive Leeds Castle. -

Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Archaeological Evaluation by Graham Hull Site Code: ABR14 ABR15/191 (TQ 4385 8400) Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham An Archaeological Evaluation for Wolford Ltd by Graham Hull Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code: ABR14 March 2016 Summary Site name: Abbey Retail Park (North), Abbey Road, Barking, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Grid reference: TQ 4385 8400 (site centre) Site activity: Archaeological Evaluation Date and duration of project: 18th - 25th February 2016 Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Graham Hull Site code: ABR14 Area of site: 2.07ha Summary of results: Five evaluation trenches were excavated. Three located archaeological features, deposits and finds that date from the Roman, Saxon, medieval and post-medieval periods. A possible Saxon ditch was found. A deposit model based on borehole logs, previous archaeological excavations, evaluation trenching and cartographic study identified a geological discontinuity with alluvium to the west and north of the site and glacial tills to the east and south-east. Finds include Roman and medieval brick and tile, Saxon, medieval and post-medieval pottery, animal bone and worked timber. The evaluation trenching has provided further evidence for Saxon and medieval activity associated with Barking Abbey. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited at The Museum of London in due course, with accession code ABR14. -

At Barking Riverside

PARKLANDS 1–3 BEDROOM APARTMENTS 3–4 BEDROOM HOUSES BARKING RIVERSIDE WILL DELIVER 10,800 HOMES AND 65,000 SQ. M. OF COMMERCIAL SPACE OVER 178 HECTARES Computer generated image. BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 1 2KM OF SOUTH-FACING RIVER THAMES FRONTAGE Computer generated image. 2 BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 3 WELCOME TO PARKLANDS AT BARKING RIVERSIDE. A brand new neighbourhood for Parklands, the first phase of new London, Barking Riverside is a vibrant homes to launch on site with L&Q, COME HOME new district, sitting alongside 2km of is a collection of one to four bedroom majestic River Thames frontage. contemporary houses and apartments. Once completed, the pioneering Each home will bring together a perfect TO A BRAND NEW development will offer 10,800 new blend of comfort, architecture, design homes, alongside shops, restaurants and impeccable eco-credentials, where and leisure and sports facilities. There you can live the life you want to live, will be public parks and river walkways, and live it in style. ADVENTURE excellent new schools with state-of- the-art facilities, and a new London Overground station, all in close proximity of central London. 4 BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 5 A VIBRANT COMMUNITY Be part of a brand new, thriving community at Barking Riverside. Set to be one of the most dynamic new destinations in the capital, once completed, Barking Riverside’s District Centre will include an impressive 65,000 square metres of commercial floorspace – home to shopping outlets, restaurants, bars and cafés. A growing number of businesses are already making their mark on the East London development. -

Iron Age Romford: Life Alongside the River During the Mid-First Millennium Bc

IRON AGE ROMFORD: LIFE ALONGSIDE THE RIVER DURING THE MID-FIRST MILLENNIUM BC Barry Bishop With contributions by Philip Armitage and Damian Goodburn SUMMARY All written and artefactual material relating to the project, including the post-excavation Excavation alongside the River Rom in Romford assessment detailing the circumstances and revealed features of Early to Middle Iron Age date, methodology of the work, will be deposited including a hollow (possibly the remains of a structure), with the London Archaeological Archive and pits, ditches and an accumulation of worked wood. The Research Centre (LAARC) under the site hollow contained hearths and large quantities of burnt code NOT05. flint — such accumulations are usually referred to as ‘burnt mounds’. The date of the remains at Romford SITE LOCATION is significant since they substantially increase the evidence for settlement in this period in London. The site was centred on National Grid Refer- ence TQ 5075 8940, c.500m north of Romford INTRODUCTION town centre (see Fig 1), and was approximately 1 hectare in extent. Prior to the 1920s the site During October and December 2005 arch- was predominantly in agricultural use. Sub- aeological investigations were conducted at sequently a petrol garage was constructed on Romside Commercial Centre and 146—147 the North Street frontage and small industrial North Street, Romford in the London Borough units occupied other parts of the site. These of Havering (Fig 1). The investigations were were extended during the 1940s and 1950s undertaken as a requirement of a planning and continued in use until the recent redev- condition placed upon the proposed resident- elopment. -

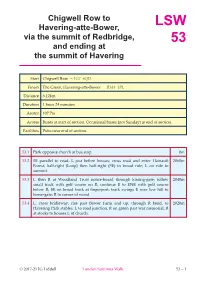

Chigwell Row to Havering-Atte-Bower, LSW Via the Summit of Redbridge, 53 and Ending at the Summit of Havering

Chigwell Row to Havering-atte-Bower, LSW via the summit of Redbridge, 53 and ending at the summit of Havering Start Chigwell Row — IG7 4QD Finish The Green, Havering-att e-Bower — RM4 1PL Distance 6.12km Duration 1 hour 24 minutes Ascent 107.7m Access Buses at start of section. Occasional buses (not Sunday) at end of section. Facilities Pubs near end of section. 53.1 Park opposite church at bus stop. 0m 53.2 SE parallel to road; L just before houses; cross road and enter Hainault 2060m Forest; half-right (Loop) then half-right (SE) to broad ride; L on ride to summit. 53.3 L then R at Woodland Trust notice-board through kissing-gate; follow 2040m small track with golf course on R; continue E to ENE with golf course below R; SE on broad track at fi ngerpost; track swings E over low hill to horse-gate; R to corner of wood. 53.4 L; cross bridleway; rise past Bower Farm and up, through R bend, to 2020m Havering Park stables; L to road junction, R on green past war memorial; R at stocks to houses L of church. © 2017-21 IG Liddell London Summits Walk 53 – 1 This section begins in the sett lement called Chigwell 53.1 Row, on the east side of the park. The “King’s Well” which gave Chigwell its name was situated in the Chigwell Row area. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the population of the small village grew: you will have passed the nonconformist chapel of that era as you entered the park coming from Grange Hill. -

A13 Riverside Tunnel Road to Regeneration the Tunnel Is Essential to East London and Thames Gateway’S Economic Success the A13 Riverside Tunnel Road to Regeneration

The A13 Riverside Tunnel Road to Regeneration The tunnel is essential to East London and Thames Gateway’s economic success The A13 Riverside Tunnel Road to Regeneration Thank you for taking the trouble to find out more about the proposed A13 Riverside Tunnel. The tunnelling of a 1.3km stretch of the A13 will not only improve traffic flow along this key route, mitigating the two notorious bottlenecks at the Lodge Avenue and Renwick Road junctions, but will also transform a severely blighted area. As well as creating a new neighbourhood of over 5,000 homes called Castle Green, the tunnel will act as a catalyst for the building of another 28,300 homes in London Riverside, while creating over 1,200 jobs and unlocking significant business and commercial growth in the surrounding area. The tunnel is essential to east London and the Thames Gateway’s economic success and will stimulate growth along its route as well as easing congestion. It also signifies a new way of working in this country adapted from successful models from other European cities. A large proportion of the scheme could be self-financing, with the majority of the funding being generated by the tunnel itself, through the land value uplift and sale of the homes, the community infrastructure levy and new homes bonus. If the government also supports our proposal for stamp duty devolution in Castle Green, then this would mean further significant funding for the scheme could be secured. Cllr Darren Rodwell Cllr Roger Ramsey Leader of Barking and Dagenham Council Leader of Havering Council Road to Regeneration 03 About the A13 The A13 is one of the busiest arterial routes into the capital, connecting the county of Essex with central London. -

Buses from Grange Hill

Buses from Grange Hill 462 FR Limes Farm Estate O Copperfield GH D A LL L Hail & Ride MANOR ROA section AN E Manor Road C St. Winifred’s Church D Grange Hill M AN W A AR MANOR ROAD FO REN Grange Hill C RD T. LONG B WAY G R Manford Way G E Manford Primary School CRE RANGE E N SCEN Brocket Way T Manford Way Hainault Health Centre Destination finder Destination Bus routes Bus stops Destination Bus routes Bus stops B L Barkingside High Street 462 ,a ,c Limes Farm Estate Copperfield 462 ,b ,d Hainault Waverley Gardens Longwood Gardens 462 ,a ,c The Lowe Beehive Lane 462 ,a ,c M Brocket Way 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c C Hainault Health Centre Chadwell Heath o High Road 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c Manford Primary School Chadwell Heath Lane 362 ,c Manor Road St. Winifred's Church 462 ,b ,d Elmbridge Road New North Road Cranbrook Road for Valentines Park 462 ,a ,c Harbourer Road Marks Gate Billet Road 362 ,c E Eastern Avenue 462 ,a ,c N New North Road Harbourer Road 362 ,c Elmbridge Road 462 ,a ,c New North Road Yellow Pine Way 362 ,c F Buses from Grange Hill Fairlop 462 ,a ,c BusesR from Grange Hill Romford Road 362 ,c Forest Road New North Road Fremantle Road 462 ,a ,c Hainault Forest Golf Club for Fairlop Waters Yellow Pine Way Barkingside High Street Boulder Park Rose Lane Estate 362 ,c Forest Road 462 ,a ,c 462 for Fairlop Waters Boulder Park FR Limes Farm Estate W Copperfield O D Fullwell Cross for Leisure Centre 462 ,a ,c WhaleboneGH Lane North 362 ,c A Romford RoadLL L Hail & Ride G MANOR ROA section WhaleboneAN Lane North 362 ,c Gants Hill 462 ,a ,c Fairlop Romford Road Whalebone GroveE Manor Road Hainault Forest Golf Club H Woodford Avenue C 462 ,a ,c St. -

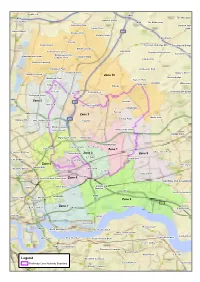

Legend Woolwich Common

Holdbrook M11 M25 The Woodman Genesis Slade Freezy Water M25 The Wilderness Sunshine Plain Berwick Ham Copley Plain Lawns Enfield Wash M11 Rushey Plain Debden Green Birchfield Clearing Sewardstone Passingford Bridge Mill Passingford Bridge Debden Slade Sewardstone Green ABRIDGE Stapleford Aerodrome Curtismill Green Whitehouse Plain Stewardstone Green Ludgate Plain LOUGHTON Lambourne Sewardstonebury Chingford Plain Lambourne End Roebuck Green Nuper's Hatch Chingford Green Whitehall Plain Bournebridge Taylor's Plain Sandhills Wilderness Friday Hill Cabin Hill Hillside The Lops Havering-atte-Bower The Green CHIGWELL Brickfields Chingford Hatch A406 M11 Hainault Hale End A406 Woodford Bridge Elmbridge Fairlop A406 Marks Gate M11 Fairlop Plain Higham Hill WALTHAM FOREST Clayhall A12 Upper Walthamstow Snaresbrook Aldborough Hatch A12 ROMFORD Nightingale Green Redbridge REDBRIDGE Lincoln Island Cranbrook Leytonstone Leyton Marshes Becontree Heath Aldersbrook ILFORD Goodmayes Lea Bridge Wanstead Flats The Chase Temple Mills Hackney Marsh Little Ilford Open Space Loxford Becontree Homerton Plashet E20 Stratford New FTorwenst Gate BARKING AND DAGENHAM West Ham BARKING Old Ford Wallend A13 South Hornchurch NEWHAM A406 Globe Town Mill Meads Bromley A13 Creekmouth Bow Common A13 RAINHAM A13 Ratcliff Cyprus A13 Docklands Thamesmead A102 North Greenwich North Woolwich West Thamesmead Coldharbour Lower Belvedere Cubitt Town New Charlton Royal Arsenal West Lesnes Abbey A102 CHARLTON Plumstead Common Bostall Heath West Heath ERITH Parkside Legend Woolwich Common Redbridge Local Authority Boundary East Wickham North End St Johns Eltham Common A2. -

Barking and Dagenham Is Supporting Our Children and Young People Like

this Barking and Dagenham Working with a range of is supporting our children organisations, we’re running and young people like exciting FREE holiday clubs never before! for children and young people right across the borough who are eligible. To find out more about each programme, and to book your place, visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/free-summer-activities. Each activity includes a healthy lunch. For free activities in the borough for all families visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/newme-healthy-lifestyle This provision is funded through the Department for Education’s Holiday Activities and Food Programme. #HAF2021. Take part in a summer to remember for Barking and Dagenham! Location Venue Dates Age Group 8 to 11 years IG11 7LX Everyone Active at Abbey Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years 4 to 7 years RM10 7FH Everyone Active at Becontree Heath Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 8 to 11 years 12 to 16 years 8 to 11 years RM8 2JR Everyone Active at Jim Peters Stadium Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years IG11 8PY Al Madina Summer Fun Programme at Al Madina Mosque Monday 2 August to Thursday 26 August 5 to 12 years RM8 3AR Ballerz at Valence Primary School Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 5 to 11 years RM8 2UT Subwize at The Vibe Tuesday 3 August to Saturday 28 August 7 to 16 years Under 16 RM10 9SA Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Park Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 6 August years Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Greatfields Under 16 IG11 0HZ Monday 9 August to Friday 20 -

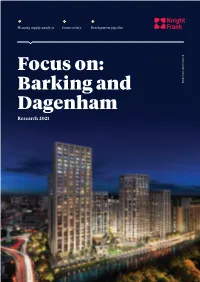

Barking and Dagenham Report 2021 Barking and Dagenham Report 2021

Housing supply analysis Connectivity Development pipeline Focus on: Barking and knightfrank.com/research Dagenham Research 2021 BARKING AND DAGENHAM REPORT 2021 BARKING AND DAGENHAM REPORT 2021 50% below asking prices 1km around Average disposable income is expected developments coming forward including Poplar Station. to rise 51% over the next decade. Growth at urban village Abbey Quay which is WHAT DOES THE NEXT On the rental side, a similar story in GVA, a measure of goods and services adjacent to Barking town centre by the emerges with average asking rents produced in an area, is expected to climb River Roding, and as part of the 440-acre DECADE LOOK LIKE FOR for a two-bedroom flat in the vicinity around a fifth. Barking Riverside masterplan. of Barking Station currently £1,261 BARKING & DAGENHAM? per month and £975 per month for Buyer preferences Dagenham Dock. This is 10% lower than The pandemic has encouraged Fig 3. Housing delivery test: asking rents around Limehouse Station, homebuyers to seek more space both Barking & Dagenham inside and out, while the experience of 2,500 uu the past year has, for some individuals, The level of new highlighted the importance of having 2,000 Faster transport connections and a growing local economy are development in Barking better access to riverside locations or supporting extensive regeneration in the area. & Dagenham has not kept green space. 1,500 pace with housing need Our latest residential client survey confirmed this, with 66% of respondents 1,000 uu Freeport status and new film studios More homes are planned, with around over that same period and a 3% rise in now viewing having access to a garden Annual Housing Target combined with the imminent arrival of 13,500 units in the development pipeline, nearby Tower Hamlets, which includes or outdoor space as a higher priority 500 historic City of London markets, Crossrail according to Molior, whichwill be delivered Canary Wharf. -

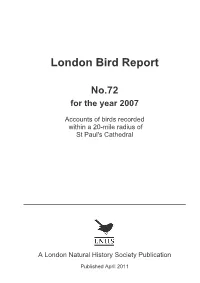

LBR 2007 Front Matter V5.1

1 London Bird Report No.72 for the year 2007 Accounts of birds recorded within a 20-mile radius of St Paul's Cathedral A London Natural History Society Publication Published April 2011 2 LONDON BIRD REPORT NO. 72 FOR 2007 3 London Bird Report for 2007 produced by the LBR Editorial Board Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements – Pete Lambert 5 Rarities Committee, Recorders and LBR Editors 7 Recording Arrangements 8 Map of the Area and Gazetteer of Sites 9 Review of the Year 2007 – Pete Lambert 16 Contributors to the Systematic List 22 Birds of the London Area 2007 30 Swans to Shelduck – Des McKenzie Dabbling Ducks – David Callahan Diving Ducks – Roy Beddard Gamebirds – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Divers to Shag – Ian Woodward Herons – Gareth Richards Raptors – Andrew Moon Rails – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Waders – Roy Woodward and Tim Harris Skuas to Gulls – Andrew Gardener Terns to Cuckoo – Surender Sharma Owls to Woodpeckers – Mark Pearson Larks to Waxwing – Sean Huggins Wren to Thrushes – Martin Shepherd Warblers – Alan Lewis Crests to Treecreeper – Jonathan Lethbridge Penduline Tit to Sparrows – Jan Hewlett Finches – Angela Linnell Buntings – Bob Watts Appendix I & II: Escapes & Hybrids – Martin Grounds Appendix III: Non-proven and Non-submitted Records First and Last Dates of Regular Migrants, 2007 170 Ringing Report for 2007 – Roger Taylor 171 Breeding Bird Survey in London, 2007 – Ian Woodward 181 Cannon Hill Common Update – Ron Kettle 183 The establishment of breeding Common Buzzards – Peter Oliver 199