London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Section 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microbiological Examination of Water Contact Sports Sites in the River Thames Catchment I989

WP MICROBIOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF WATER CONTACT SPORTS SITES IN THE RIVER THAMES CATCHMENT I989 E0 E n v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE HEAD OFFICE K10 House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West. Almondsbury, Bristol RS32 4UD BIOLOGY (EAST) BIOLOGY (WEST) THE GRANGE FOBNEY MEAD CROSSBROOK STREET ROSE KILN LANE WALTHAM CROSS READING HERTS BERKS EN8 8lx RG2 OSF TEL: 0992 645075 TEL: 0734 311422 FAX: 0992 30707 FAX: 0734 311438 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY ■ tin aim 042280 CONTENTS PAGE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 2 RESULTS 7 DISCUSSION 18 CONCLUSION 20 RECOMMENDATIONS 20 REFERENCES 21 MICROBIOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF WATER CONTACT SPORTS SITES IN THE RIVER THAMES CATCHMENT 1989 SUMMARY Water samples were taken at sixty-one sites associated with recreational use throughout the River Thames catchment. Samples were obtained from the main River Thames, tributaries, standing waters and the London Docks. The samples were examined for Total Coliforms and Escherichia coli to give a measure of faecal contamination. The results were compared with the standards given in E.C. Directive 76/I6O/EEC (Concerning the quality of bathing water). In general, coliform levels in river waters were higher than those in standing waters. At present, there are three EC Designated bathing areas in the River Thames catchment, none of which are situated on freshwaters. Compliance data calculated in this report is intended for comparison with the EC Directive only and is not statutory. Most sites sampled complied at least intermittently with the E.C. Imperative levels for both Total Coliforms and E.coli. -

Barking and Dagenham Is Supporting Our Children and Young People Like

this Barking and Dagenham Working with a range of is supporting our children organisations, we’re running and young people like exciting FREE holiday clubs never before! for children and young people right across the borough who are eligible. To find out more about each programme, and to book your place, visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/free-summer-activities. Each activity includes a healthy lunch. For free activities in the borough for all families visit www.lbbd.gov.uk/newme-healthy-lifestyle This provision is funded through the Department for Education’s Holiday Activities and Food Programme. #HAF2021. Take part in a summer to remember for Barking and Dagenham! Location Venue Dates Age Group 8 to 11 years IG11 7LX Everyone Active at Abbey Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years 4 to 7 years RM10 7FH Everyone Active at Becontree Heath Leisure Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 8 to 11 years 12 to 16 years 8 to 11 years RM8 2JR Everyone Active at Jim Peters Stadium Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 12 to 16 years IG11 8PY Al Madina Summer Fun Programme at Al Madina Mosque Monday 2 August to Thursday 26 August 5 to 12 years RM8 3AR Ballerz at Valence Primary School Monday 26 July to Friday 20 August 5 to 11 years RM8 2UT Subwize at The Vibe Tuesday 3 August to Saturday 28 August 7 to 16 years Under 16 RM10 9SA Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Park Centre Monday 26 July to Friday 6 August years Big Deal Urban Arts Camp from Studio 3 Arts at Greatfields Under 16 IG11 0HZ Monday 9 August to Friday 20 -

Barking Riverside: 1 Heritage and Ecology Combine to Create a Distinctive New Place

Barking Riverside: 1 Heritage and ecology combine to create a distinctive new place LDA Design is helping to turn Barking Power Station in east London 2 3 into a distinctive new riverfront town, made special by its heritage, ecology and location. Stretching 2km along the northern banks of the River Thames, this ambitious new 180-hectare development is one of the UK’s largest regeneration projects. It will provide more than 10,000 homes, as well as new schools, and commercial and cultural spaces. LDA Design, in partnership with WSP, is delivering a Strategic Infrastructure Scheme (SIS), providing a framework for Barking Riverside’s parks, public realm and green spaces; its highways and streetscapes, flood defences, services, utilities and drainage. Starting with a clear vision based on extensive public consultation, our ‘First life’ approach aims to create a welcoming place where people belong. Client Barking Riverside Ltd. Services Masterplanning, Landscape Architecture Location Critical to its success is excellent connectivity. A new train station Barking, Barking & Dagenham and additional bus routes and cycle network will help to integrate Area Partners 180 ha Barking Riverside with its surroundings. The landscape strategy is key L&Q, WSP, Barton Willmore, Arcadis, Laing O’Rourke, Schedule to creating a safe, sociable, sustainable place to live. Proposals include Liftschutz Davidson Sandilands, DF Clark, Future City, 2016 - ongoing Temple, Jestico + Whiles, Tim O’Hare Associates, Envac, terraced seating with river views and a new park that moves into IESIS, XCo2 1 Barking Park 3D masterplan serene wetlands. New habitats will help boost biodiversity. 2 Community green 3 Terraced seating overlooking swales 1 1 Eastern Waterfront, looking west. -

Best Parkrun

Best Parkrun Ilford AC Park Run List 1 15.39 Blair Mcwhirter 14/10/2017 North Hagley Park Hagley Park Run SM Chelmsford Park 2 15.51 Malcolm Muir 29/06/2013 Central Park SM Run 3 16.01 Paul Grange 15/02/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 4 16.05 Ahmed Abdulle 15/07/2017 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U20 5 16.24 Ben Jones 23/04/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM Albert Park Run 6 16.24 Tom Gardner 08/02/2020 Albert Park SM (Australia) 7 16.35 Gary Coombes 01/01/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 Shepton Mallett 8 16.54 Mungo Prior 21/12/2019 Collett Park U20 Parkrun 9 17.01 Steve Philcox 10/09/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run V40 10 17.04 Jak Wright 27/07/2019 Barking Park Barking Park Run U17 11 17.18 Iain Knight 30/04/2011 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 12 17.26 Kevin Newell 29/11/2014 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 13 17.28 Aaron Samuel 17/02/2018 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 14 17.29 Sam Rahman 01/11/2014 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run SM 15 17.31 Bradley Deacon 15/02/2020 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 16 17.40 Ryan Holeyman 14/03/2020 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run U15 17 17.42 Kevin Wotton 12/05/2012 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run V40 18 17.43 Usamah Patel 14/09/2013 Valentines Park Valentines Park Run U17 19 17.46 Robin Mcnelis 12/03/2016 Raphael Park Raphaels Park Run V40 20 17.47 James Rigby 06/07/2017 Raphael Park Raphael Park Run SM 21 18.1 Haydn Newland 25/12/2019 Barking Park Barking Park Run SM 22 18.11 Joseph Grange 22/02/2020 Barking Park Barking -

Bird Species I Have Seen World List

bird species I have seen U.K tally: 276 US tally: 394 Total world: 1,495 world list 1. Abyssinian ground hornbill 2. Abyssinian longclaw 3. Abyssinian white-eye 4. Acorn woodpecker 5. African black-headed oriole 6. African drongo 7. African fish-eagle 8. African harrier-hawk 9. African hawk-eagle 10. African mourning dove 11. African palm swift 12. African paradise flycatcher 13. African paradise monarch 14. African pied wagtail 15. African rook 16. African white-backed vulture 17. Agami heron 18. Alexandrine parakeet 19. Amazon kingfisher 20. American avocet 21. American bittern 22. American black duck 23. American cliff swallow 24. American coot 25. American crow 26. American dipper 27. American flamingo 28. American golden plover 29. American goldfinch 30. American kestrel 31. American mag 32. American oystercatcher 33. American pipit 34. American pygmy kingfisher 35. American redstart 36. American robin 37. American swallow-tailed kite 38. American tree sparrow 39. American white pelican 40. American wigeon 41. Ancient murrelet 42. Andean avocet 43. Andean condor 44. Andean flamingo 45. Andean gull 46. Andean negrito 47. Andean swift 48. Anhinga 49. Antillean crested hummingbird 50. Antillean euphonia 51. Antillean mango 52. Antillean nighthawk 53. Antillean palm-swift 54. Aplomado falcon 55. Arabian bustard 56. Arcadian flycatcher 57. Arctic redpoll 58. Arctic skua 59. Arctic tern 60. Armenian gull 61. Arrow-headed warbler 62. Ash-throated flycatcher 63. Ashy-headed goose 64. Ashy-headed laughing thrush (endemic) 65. Asian black bulbul 66. Asian openbill 67. Asian palm-swift 68. Asian paradise flycatcher 69. Asian woolly-necked stork 70. -

Shared Ownership Homes from Metropolitan

SHARED OWNERSHIP HOMES FROM METROPOLITAN 1 A collection of contemporary homes, located in the leafy Victorian suburb of Ilford, less than 30 minutes from central London. STREETS AHEAD Wanstead Park presents the unique opportunity of affordable and contemporary London living within a family focused, community orientated environment. This modern residential development offers a relaxed, suburban lifestyle and a fast, easy commute. Known as London’s ‘leafy suburb’, the green open spaces of nearby Valentines Park and Wanstead Flats compliment the traditional, close- knit neighbourly feel of this minimal, contemporary terrace style development. With a number of “outstanding” rated schools, excellent local amenities and a brief 30 minute journey to central London, this mix of three and four bedroom houses and one, two and three bedroom apartments offers the perfect foundations for family focused couples and young independent professionals. 04 05 DOWN TOWN Located in one of London’s most historic Victorian Theatre goers and film lovers will be pleased boroughs, Wanstead Park offers relaxed and leafy to find the Kenneth More Theatre and suburban living just a short walk from Ilford’s Cineworld cinema just a short walk away, dynamic and vibrant town centre. with the informative Redbridge Central Library and Museum also close by. The Exchange shopping centre and High Road are just over ten minutes walk away. Both provide an array of shops from national and international retailers. The surrounding streets offer outlets for a range of budgets and needs, while the slightly closer Cranbrook Road is home to a wide selection of independent eateries and stores covering cuisines and cultures from across the world. -

LCT Update 120521

UPDATE MAY 12, 2021 1 SUMMARY Between 2018 and the end of 2021, the London Cricket Trust will have overseen the installation of 61 non-turf pitches and 13 net facilities across the capital. In Phases 1 and 2, in 2018 and 2019, 36 non-turf pitches and four net facilities were created and 66 cricket starter-kits were donated to primary and high schools. In Phase 3, in 2020, running into 2021, and Phase 4, in 2021, a further 25 NTP’s and nine net facilities will be completed and available for use. In this process, LCT has emerged as a lean, focused organisation through which the four county boards - Essex, Kent, Middlesex and Surrey - work eficiently and effectively not only together but also in conjunction with the ECB, measurably increasing cricket participation in the capital. Advantage Sports Management (ASM) is responsible for the day-to-day management of the LCT, reporting to the four trustees, identifying potential sites and regularly checking each venue, ensuring maintenance, maximising participation. ASM deals on a daily basis with county boards, ECB, councils, park management, schools, clubs, other cricket organisations and members of the public. ASM undertakes this significant volume of work pro bono, and receives an annual contribution towards expenses from each of the four counties. 1 THE LONDON CRICKET TRUST Putting cricket back into London’s parks 2 Index PHASE 1 (2018) and PHASE 2 (2019) maintenance report PAGE 4 PHASE 3 (2020) maintenance report and update PAGE 10 PHASE 4 (2021) update PAGE 17 PHASE 5 (2022) proposals PAGE 18 LCT WEBSITE PAGE 19 ACTIVATION plans PAGE 20 3 PHASE 1 (2018) and PHASE 2 (2019) AVERY HILL PARK Local Authority Greenwich County Kent LCT Facility 1 x NTP Completion date 2018 Most recent ASM site visit 21.04.21 The NTP is in decent condition and the outfield has also been maintained. -

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham OPEN PROJECT

12/4/2017 GLA OPS MAYOR OF LONDON | Logout () OPEN PROJECT SYSTEM We use cookies to ensure we give you the best experience on our website. Find out more about cookies in our privacy policy (https://www.london.gov.uk/about-us/privacy-policy) London Borough of BACK Barking and Dagenham Status: Assess Change Management Report Project ID: P10955 London Borough of London Borough of Culture Culture 12 unapproved blocks Collapse all blocks () Project Details Jump to General Information () New block with edits There is no approved version of this block Unapproved changes on 28/11/2017 by Project title London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Bidding arrangement London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Organisation name London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Programme selected London Borough of Culture Project type selected London Borough of Culture https://ops.london.gov.uk/#/change-report/10955 1/41 12/4/2017 GLA OPS General Information Jump to Contact with us () New block with edits There is no approved version of this block Unapproved changes on 30/11/2017 by Name of Borough. Barking & Dagenham Borough address. London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Room 216 Barking Town Hall IG11 7LU. Name of contact person. Position held. Commissioning Director - Culture and Recreation Directorate. Growth and Homes Department/Business Unit. Culture and Recreation Telephone number. 020 8227 E-mail address. lbbd.gov.uk Contact with us Jump to Project Overview () New block with edits There is no approved version of this block Unapproved changes on 30/11/2017 -

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award Winners

Green Flag Award Winners 2019 England East Midlands 125 Green Flag Award winners Park Title Heritage Managing Organisation Belper Cemetery Amber Valley Borough Council Belper Parks Amber Valley Borough Council Belper River Gardens Amber Valley Borough Council Crays Hill Recreation Ground Amber Valley Borough Council Crossley Park Amber Valley Borough Council Heanor Memorial Park Amber Valley Borough Council Pennytown Ponds Local Nature Reserve Amber Valley Borough Council Riddings Park Amber Valley Borough Council Ampthill Great Park Ampthill Town Council Rutland Water Anglian Water Services Ltd Brierley Forest Park Ashfield District Council Kingsway Park Ashfield District Council Lawn Pleasure Grounds Ashfield District Council Portland Park Ashfield District Council Selston Golf Course Ashfield District Council Titchfield Park Hucknall Ashfield District Council Kings Park Bassetlaw District Council The Canch (Memorial Gardens) Bassetlaw District Council A Place To Grow Blaby District Council Glen Parva and Glen Hills Local Nature Reserves Blaby District Council Bramcote Hills Park Broxtowe Borough Council Colliers Wood Broxtowe Borough Council Chesterfield Canal (Kiveton Park to West Stockwith) Canal & River Trust Erewash Canal Canal & River Trust Queen’s Park Charnwood Borough Council Chesterfield Crematorium Chesterfield Borough Council Eastwood Park Chesterfield Borough Council Holmebrook Valley Park Chesterfield Borough Council Poolsbrook Country Park Chesterfield Borough Council Queen’s Park Chesterfield Borough Council Boultham -

Good Parks for London 2017

''The measure of any great civilisation is in its cities, and the measure of a city's greatness is to be found in the quality of its public spaces, it's parks and squares.'' John Ruskin Sponsored by Part of Capita plc Contents Foreword..........................................................3 Part 2 Introduction.....................................................4 Signature Parks and green spaces City of London - Open space beyond the square mile...38 Overall scores...................................................8 Lee Valley Regional Park Authority............................40 Thamesmead - London’s largest housing landscape......42 Part 1 The Royal Parks......................................................43 Good Parks for London Criteria Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park..................................45 1. Public Satisfaction...........................................10 Landscape contractors 2. Awards for quality...........................................12 idverde - A whole system approach............................47 3. Collaboration with other Boroughs..................14 Glendale - Partnership in practice.............................49 4. Events.............................................................16 5. Health, fitness and well-being.........................20 Capel Manor - London’s land based college.........50 6. Supporting nature...........................................24 7. Community involvement.................................28 8. Skills development..........................................30 Valuing our parks -

Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley Extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake

THE EXECUTIVE 8 FEBRUARY 2005 REPORT FROM THE DIRECTOR OF REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT EASTBROOKEND COUNTRY PARK (BEAM VALLEY FOR DECISION EXTENSION), MAYESBROOK PARK LAKE (SOUTH) AND PARSLOES PARK (SQUATTS) - DECLARATION OF LOCAL NATURE RESERVES This report concerns a strategic matter and is therefore reserved to the Executive by the Scheme of Delegation. Summary The designation of Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’ are the second targets to be achieved under the Borough’s Local Public Service Agreement with the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Following consultation with English Nature, it is proposed to designate these sites as the Borough’s latest Local Nature Reserves. This follows the designation of The Chase as a Local Nature Reserve (2001) and Eastbrookend Country Park (2003) Plans showing the proposed areas to be designated are attached (Appendices A-C) Recommendation The Executive is recommended to: (i) approve the declaration of Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension), Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’, as marked on the attached plans, as Local Nature Reserves (LNR’s); and (ii) authorise Officers to issue the necessary Notices and enter into the necessary legal arrangements to enable the Declarations to take place. Reason The designation of these sites as Local Nature Reserves will assist the Council in achieving its Community Priorities of ‘Making Barking and Dagenham Cleaner, Greener and Safer’ and ‘Raising General Pride in the Borough’. Wards Affected Village Ward; - Eastbrookend Country Park (Beam Valley extension); Mayesbrook Ward; - Mayesbrook Park Lake (South) and Parsloes Park ‘Squatts’ Contact: Mike Levett Senior Park Development Officer Tel: 020 - 8227 3387 Fax: 020 - 8227 3129 Minicom: 020 - 8227 3042 E-mail: [email protected] 1. -

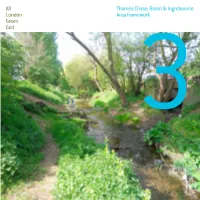

Thames Chase, Beam & Ingrebourne Area Framework

All Thames Chase, Beam & Ingrebourne London Area framework Green Grid 3 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 12 Vision 14 Objectives 18 Opportunities 20 Project Identification 22 Project update 24 Clusters 26 Projects Map 28 Rolling Projects List 32 Phase Two Delivery 34 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 55 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GG03 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA03 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . Cover Image: The river Rom near Collier Row As a key partner, the Thames Chase Trust welcomes the opportunity to continue working with the All Foreword London Green Grid through the Area 3 Framework.